6.6 Entrance Corner (Linear Inequalities)

Constant and Variables

A variable is a symbol that represents a value that can change, while a constant is a symbol or number that represents a fixed value that does not change. Variables are used for unknown or changing quantities (like \(x\) in \(3 x+4\) ), whereas constants are for values that remain the same (like the 3 and 4 in \(3 x+4\) ).

Dependent and Independent Variables

Variables are further distinguished as being either a dependent variable or an independent variable. Independent variables are regarded as inputs to a system and may take on different values freely.

Dependent variables are those values that change as a consequence to changes in other values in the system.

For example, \(y=f(x)=3 x^2\), here we can take \(x\) as any real value, hence \(x\) is independent variable. But value of \(y\) depends on value of \(x\), hence \(y\) is dependent variable.

What is Function

A function is a rule that assigns to each input value (from a set called the domain) exactly one output value (from a set called the range). This relationship can be visualized as a machine that takes an input, applies a rule, and produces a single, unique output. Functions can be expressed as algebraic equations ( \(y=2 x\) ), written out in words, or shown as a graph.

To make it simple, for the function \(f(x)\), all of the possible \(x\) values constitute the domain, and all of the values \(f(x)\) ( \(y\) on the \(x\)-y plane) constitute the range.

Example 1: A function is defined as \(f(x)=x^2-3 x\).

(i) Find the value of \(f(2)\).

(ii) Find the value of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) for which \(\boldsymbol{f}(\boldsymbol{x})=\mathbf{4}\).

Solution:

(i) \(f(2)=(2)^2-3(2)=-2\)

(ii)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(x)=4 \\

& \Rightarrow x^2-3 x=4 \quad \Rightarrow x^2-3 x-4=0 \\

& \Rightarrow(x-4)(x+1)=0 \quad \Rightarrow x=4 \text { or }-1

\end{aligned}

\)

This means \(f(4)=4\) and \(f(-1)=4\).

Example 2: If \(f\) is linear function and \(f(2)=4, f(-1) =3\), then find \(f(x)\).

Solution: Let linear function is \(f(x)=a x+\mathrm{b}\)

Given \(\quad f(2)=4 \Rightarrow 2 a+b=4 \dots(1)\)

Also \(\quad f(-1)=3 \quad \Rightarrow-a+b=3 \dots(2)\)

Solving (1) and (2) we get \(a=\frac{1}{3}\) and \(b=\frac{10}{3}\)

Hence, \(f(x)=\frac{x+10}{3}\)

Example 3: A function is defined as \(f(x)=\frac{x^2+1}{3 x-2}\). Can \(f(x)\) take a value 1 for any real \(x\) ?

Also find the value/values of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) for which \(\boldsymbol{f} \boldsymbol{(} \boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{)}\) takes the value 2.

Solution: Here \(f(x)=\frac{x^2+1}{3 x-2}=1\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad x^2+1=3 x-2 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x^2-3 x+3=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Now this equation has no real roots as \(D<0\).

Hence, value of \(f(x)\) cannot be 1 for any real \(x\).

For \(f(x)=2\) we have \(\frac{x^2+1}{3 x-2}=2\)

or \(\quad x^2+1=6 x-4\) or \(x^2-6 x+5=0\)

or \(\quad(x-1)(x-5)=0\)

or \(\quad x=1,5\)

Example 4: Find the values of \(x\) for which the following functions are defined. Also find all possible values which functions take.

(i) \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x+1}\)

(ii) \(f(x)=\frac{x-2}{x-3}\)

(iii) \(f(x)=\frac{2 x}{x-1}\)

Solution:

(i) \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x+1}\) is defined for all real values of \(x\) except when \(x+1=0\)

Hence, \(f(x)\) is defined for \(x \in R-\{-1\}\).

Let \(y=\frac{1}{x+1}\)

Here we cannot find any real \(x\) for which \(y=\frac{1}{x+1}=0\)

For \(y\) other than ‘ 0 ‘, there exists a real number \(x\).

Hence, \(\frac{1}{x+1} \in R-\{0\}\).

(ii) \(f(x)=\frac{x-2}{x-3}\) is defined for all real values of \(x\) except when \(x-3=0\).

Hence, \(f(x)\) is defined for \(x \in R-\{3\}\)

Let \(y=\frac{x-2}{x-3}\)

Here we cannot find any real \(x\) for which \(y=\frac{x-2}{x-3}=1\)

Note: When \(\frac{x-2}{x-3}=1\), we have \(x-2=x-3\) or \(-2=-3\) which is absurd.

For \(y\) other than ‘ 1 ‘ there exists a real number \(x\).

Hence, \(\frac{1}{x+1} \in R-\{1\}\).

(iii) \(f(x)=\frac{2 x}{x-1}\) is defined for all real values of \(x\) except when \(x-1=0\)

Hence, \(f(x)\) is defined for \(x \in R-\{1\}\)

Let \(y=\frac{2 x}{x-1}\)

Here we cannot find any real \(x\) for which \(y=\frac{2 x}{x-1}=2\)

Note: When \(\frac{2 x}{x-1}=2\), we have \(2 x=2 x-2\) or \(0=-2\) which is absurd.

For \(y\) other than ‘ 2 ‘ there exists a real number \(x\).

Hence, \(\frac{2 x}{x-1} \in R-\{2\}\).

Example 5: If \(f(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{l}x^3, x<0 \\ 3 x-2,0 \leq x \leq 2, \text { then find } \\ x^2+1, x>2\end{array}\right.\)

the value of \(f(-1)+f(1)+f(3)\).

Also find the value/values of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) for which \(\boldsymbol{f} \boldsymbol{(} \boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{)} \boldsymbol{=} \mathbf{2}\).

Solution: Here function is differently defined for three different intervals mentioned. For \(x=-1\), consider \(f(x)=x^3\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad f(-1)=-1

\)

For \(x=1\), consider \(f(x)=3 x-2\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad f(1)=1

\)

For \(x=3\), consider \(f(x)=x^2+1\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow f(3)=10 \\

& \Rightarrow f(-1)+f(1)+f(3)=-1+1+10=10

\end{aligned}

\)

Also when \(f(x)=2\),

for \(x^3=2, x=2^{1 / 3}\), which is not possible as \(x<0\).

for \(3 x-2=2, x=4 / 3\), which is possible as \(0 \leq x \leq 2\).

For \(x^2+1=2, x= \pm 1\), which is not possible as \(x>2\).

Hence, for \(f(x)=2\), we have \(x=4 / 3\).

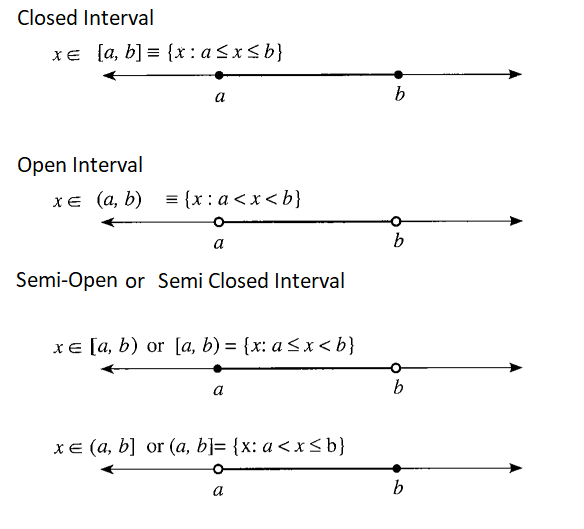

Intervals

The set of numbers between any two real numbers is called interval. The following are the types of interval.

Note:

- \(A\) set of all real numbers can be expressed as \((-\infty, \infty)\)

- \(x \in(-\infty, a) \cup(b, \infty) \Rightarrow x \in R-[a, b]\)

- \(x \in(-\infty, a] \cup[b, \infty) \Rightarrow x \in R-(a, b)\)

Inequations

A statement involving variable ( \(s\) ) and the sign of inequality viz., \(>\) or, \(<\), or, \(\geq\) or, \(\leq\) is called an inequation. An inequation may contain one or more variables. Also, it may be linear or quadratic or cubic etc.

Inequations \(2 x-3<0,3 y \geq 5, \frac{x}{2}-7 \leq 0, \frac{2 x-3}{4} \geq-\frac{x}{2}+7\) and \(-2+t \leq \frac{5}{3}\) are linear inequations in one variable.

\(2 x-3 y<6\), \(x+y \geq-4\) are linear inequations in two variables. Inequations of the form \(\frac{2 x-3}{x-1}<4, x^2-5 x+6 \geq 0\) etc are not linear inequations.

Inequalities

Inequalities are broadly categorized as comparative (comparing two values) or restrictive (defining a range of values for one quantity) in a mathematical context. Linear and nonlinear inequalities are based on the expressions involved. Linear inequalities have variables to the first power, like \(2 x+5 \leq 10\), which results in a straight line on a graph. Nonlinear inequalities involve variables with powers greater than one, or other functions like those in the example \(x^2-4 x+3>0\), which results in a curved line (a parabola) on a graph.

Some Important Facts about Inequalities

The following are some very useful points to remember:

- \(a \leq b\) either \(a<b\) or \(a=b\)

- \(a<b\) and \(b<c \Rightarrow a<c\) (transition property)

- \(a<b \Rightarrow-a>-b\), i.e., inequality sign reverses if both sides are multiplied by a negative number

- \(a<b\) and \(c<d \Rightarrow a+c<b+d\) and \(a-d<b-c\).

- If both sides of inequality are multiplied (or divided) by a positive number, inequality does not change. When both of its sides are multiplied (or divided) by a negative number, inequality gets reversed.

i.e., \(a<b \Rightarrow k a<k b\) if \(k>0\) and \(k a>k b\) if \(k<0\) - \(0<a<b \Rightarrow a^r<b^r\) if \(r>0\) and \(a^r>b^r\) if \(r<0\)

- \(a+\frac{1}{a} \geq 2\) for \(a>0\) and equality holds for \(a=1\)

- \(a+\frac{1}{a} \leq-2\) for \(a<0\) and equality holds for \(a=-1\)

- Squaring an inequality:

If \(a<b\), then \(a^2<b^2\) does not follows always:

Consider the following illustrations:

\(2<3 \Rightarrow 4<9\), but \(-4<3 \Rightarrow 16>9\)

Also if \(x>2 \Rightarrow x^2>4\), but for \(x<2 \Rightarrow x^2 \geq 0\)

If \(2<x<4 \Rightarrow 4<x^2<16\)

If \(-2<x<4 \Rightarrow 0 \leq x^2<16\)

If \(-5<x<4 \Rightarrow 0 \leq x^2<25\)

In fact \(a<b \Rightarrow a^2<b^2\) follows only when absolute value of \(a\) is less than the absolute value of \(b\) or distance of \(a\) from zero is less than the distance of \(b\) from zero on real number line. - Law of reciprocal:

If both sides of inequality have same sign, while taking its reciprocal the sign of inequality gets reversed. i.e., \(a\). \(>b>0 \Rightarrow \frac{1}{a}<\frac{1}{b}\) and \(a<b<0 \Rightarrow \frac{1}{a}>\frac{1}{b}\)

But if both sides of inequality have opposite sign, then while taking reciprocal sign of inequality does not change, i.e.

\(

a<0<b \Rightarrow \frac{1}{a}<\frac{1}{b}

\)

If \(x \in[a, b] \Rightarrow\left\{\begin{array}{l}\frac{1}{x} \in\left[\frac{1}{b}, \frac{1}{a}\right], \text { if } a \text { and } b \text { have same sign } \\ \frac{1}{x} \in\left(-\infty, \frac{1}{a}\right] \cup\left[\frac{1}{b}, \infty\right), \text { if } a \text { and } b \text { have opposite signs }\end{array}\right.\) - Two important results

(a) If \(a, b \in \mathbf{R}\) and \(b \neq 0\), then

(i) \(\quad a b>0\) or \(\frac{a}{b}>0 \Rightarrow a\) and \(b\) are of the same sign.

(ii) \(a b<0\) or \(\frac{a}{b}<0 \Rightarrow a\) and \(b\) are of opposite sign.

(b) If \(a\) is any positive real number, i.e., \(a>0\), then

(i)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& |x|<a \Leftrightarrow-a<x<a \\

& |x| \leq a \Leftrightarrow-a \leq x \leq a

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& |x|>a \Leftrightarrow x<-a \text { or } x>a \\

& |x| \geq a \Leftrightarrow x \leq-a \text { or } x \geq a

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 6:

Find the values of \(\boldsymbol{x}^{\mathbf{2}}\) for the given values of \(\boldsymbol{x}\).

(i) \(x<2\)

(ii) \(x>-1\)

(iii) \(\boldsymbol{x} \geq \mathbf{2}\)

(iv) \(x<-1\)

Solution:

(i) When \(x<2\) we have \(x \in(-\infty, 0) \cup[0,2)\)

for \(x \in[0,2), x^2 \in[0,4)\)

for \(x \in(-\infty, 0), x^2 \in(0, \infty)\)

\(\Rightarrow\) for \(x<2, x^2 \in[0,4) \cup(0, \infty)\)

\(\Rightarrow x \in[0, \infty)\)

(ii) When \(x>-1\) we have \(x \in(-1,0) \cup[0, \infty)\)

for \(x \in(-1,0), x^2 \in(0,1)\)

for \(x \in[0, \infty), x^2 \in[0, \infty)\)

\(\Rightarrow\) for \(x>-1, x^2 \in(0,1) \cup[0, \infty)\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad x \in[0, \infty)\)

(iii) Here \(x \in[2, \infty)\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x^2 \in[4, \infty)

\)

(iv) Here \(x \in(-\infty,-1)\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x^2 \in(1, \infty)

\)

Example 7: Find the values of \(1 / x\) for the given values of \(\boldsymbol{x}\).

(i) \(x>3\)

(ii) \(x<-2\)

(iii) \(x \in(-1,3)-\{0\}\)

Solution:

(i) We have \(3<x<\infty\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{1}{3}>\frac{1}{x}>\frac{1}{\rightarrow \infty}(\rightarrow \infty \text { means tends to infinity }) \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 0<\frac{1}{x}<\frac{1}{3}

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) We have \(-\infty<x<-2\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{1}{\rightarrow-\infty}>\frac{1}{x}>\frac{1}{-2} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{1}{\rightarrow-\infty}>\frac{1}{x}>\frac{1}{-2} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 0>\frac{1}{x}>-\frac{1}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

(iii)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x \in(-1,3)-\{0\} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x \in(-1,0) \cup(0,3)

\end{aligned}

\)

For \(x \in(-1,0)\)

\(

\frac{1}{-1}>\frac{1}{x}>\frac{1}{\rightarrow 0^{-}}

\)

(here \(\rightarrow 0\) means value of \(x\) approaches to 0 from its left hand side or negative side)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad-1>\frac{1}{x}>-\infty \\

& \Rightarrow \quad-\infty<\frac{1}{x}<-1 \dots(1)

\end{aligned}

\)

For \(x \in(0,3)\)

\(

\frac{1}{\rightarrow 0^{+}}>\frac{1}{x}>\frac{1}{3}

\)

(here \(\rightarrow 0^{+}\)means value of \(x\) approaches to 0 from its right hand side or positive side)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \infty>\frac{1}{x}>\frac{1}{3} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{1}{3}<\frac{1}{x}<\infty \dots(2)

\end{aligned}

\)

From (1) and (2), \(\frac{1}{x} \in(-\infty,-1) \cup\left(\frac{1}{3}, \infty\right)\)

Note: For \(x \in R-\{0\}, \frac{1}{x} \in R-\{0\}\)

Example 8: Find all possible values of the following expressions:

(i) \(\frac{1}{x^2+2}\)

(ii) \(\frac{1}{x^2-2 x+3}\)

(iii) \(\frac{1}{x^2-x-1}\)

Solution:

(i) We know that \(x^2 \geq 0 x \in R\).

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x^2+2 \geq 2, \forall x \in R .

\)

or \(\quad 2 \leq\left(x^2+2\right)<\infty\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{1}{2} \geq \frac{1}{x^2+2}>0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 0<\frac{1}{x^2+2} \leq \frac{1}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) \(\frac{1}{x^2-2 x+3}=\frac{1}{(x-1)^2+2}\)

Now we know that \((x-1)^2 \geq 0 \forall x \in R\).

\(

\Rightarrow \quad(x-1)^2+2 \geq 2 \forall x \in R .

\)

or \(\quad 2 \leq(x-1)^2+2<\infty\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \frac{1}{2} \geq \frac{1}{(x-1)^2+2}>0 \\

& \Rightarrow \frac{1}{x^2-2 x+3} \in\left(0, \frac{1}{2}\right]

\end{aligned}

\)

(iii)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{1}{x^2-x-1}=\frac{1}{\left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)^2-\frac{5}{4}} \\

& \left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)^2 \geq 0, \forall x \in R \\

& \Rightarrow\left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)^2-\frac{5}{4} \geq-\frac{5}{4}, \forall x \in R

\end{aligned}

\)

For \(\frac{1}{\left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)^2-\frac{5}{4}}\), we must have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)^2-\frac{5}{4} \in\left[-\frac{5}{4}, 0\right) \cup(0, \infty) \\

& \Rightarrow \frac{1}{\left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)^2-\frac{5}{4}} \in\left(-\infty,-\frac{4}{5}\right] \cup(0, \infty)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 9: Find all possible values of the following expressions:

(i) \(\sqrt{x^2-4}\)

(ii) \(\sqrt{9-x^2}\)

(iii) \(\sqrt{x^2-2 x+10}\)

Solution:

(i) \(\sqrt{x^2-4}\)

Least value of square root is 0 when \(x^2=4\) or \(x= \pm 2\). Also \(x^2-4 \geq 0\)

Hence, \(\sqrt{x^2-4} \in[0, \infty)\).

(ii) \(\sqrt{9-x^2}\)

Least value of square root is 0 when \(9-x^2=0\) or \(x= \pm 3\).

Also, the greatest value of \(9-x^2\) is 9 when \(x=0\).

Hence, we have \(0 \leq 9-x^2 \leq 9 \Rightarrow \sqrt{9-x^2} \in[0,3]\).

(iii) \(\sqrt{x^2-2 x+10}=\sqrt{(x-1)^2+9}\)

Here, the least value of \(\sqrt{(x-1)^2+9}\) is 3 when \(x-1=0\).

Also \((x-1)^2+9 \geq 9 \Rightarrow \sqrt{(x-1)^2+9} \geq 3\)

Hence, \(\sqrt{x^2-2 x+10} \in[3, \infty)\).

For solving an inequation, we use the following rules:

- Rule 1: Same number may be added to (or subtracted from) both sides of an inequation without changing the sign of inequality.

- Rule 2: Both sides of an inequation can be multiplied (or divided) by the same positive real number without changing the sign of inequality. However, the sign of inequality is reversed when both sides of an inequation are multiplied or divided by a negative number.

- Rule 3: Any term of an inequation may be taken to the other side with its sign changed without affecting the sign of inequality.

Example 10: The solution set of the inequation \(\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{3}{5} x+4\right) \geq \frac{1}{3}(x-6)\) is

(a) \([120, \infty)\)

(b) \((-\infty, 120]\)

(c) \([0,120]\)

(d) \([-120,0]\)

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{3}{5} x+4\right) \geq \frac{1}{3}(x-6) \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{3 x+20}{5}\right) \geq \frac{1}{3}(x-6) \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{3 x+20}{10} \geq \frac{x-6}{3}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad 3(3 x+20) \geq 10(x-6) \quad\left[\begin{array}{r}

\text { Multiplying both sides by } 30 \\

\text { i.e. LCM of } 10 \text { and } 3

\end{array}\right]

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 9 x+60 \geq 10 x-60 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 9 x-10 x \geq-60-60 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad-x \geq-120 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x \leq 120 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x \in(-\infty, 120]

\end{aligned}\\

&\text { Hence, the solution set of the given inequation is }(-\infty, 120] \text {. }

\end{aligned}

\)

Remark: The solution set of simultaneous inequations is the intersection of their solution sets.

Example 11: If \(\frac{5 x}{4}+\frac{3 x}{8}>\frac{39}{8}\) and \(\frac{2 x-1}{12}-\frac{x-1}{3}<\frac{3 x+1}{4}\), then \(x\) belongs to the interval

(a) \((3, \infty)\)

(b) \((0, \infty)\)

(c) \((-\infty, 3)\)

(d) \((-\infty, 0)\)

Solution: (a) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{5 x}{4}+\frac{3 x}{8}>\frac{39}{8} \text { and } \frac{2 x-1}{12}-\frac{x-1}{3}<\frac{3 x+1}{4} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{10 x+3 x}{8}>\frac{39}{8} \text { and } \frac{2 x-1-4 x+4}{12}<\frac{3 x+1}{4} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{13 x}{8}>\frac{39}{8} \text { and } \frac{-2 x+3}{12}<\frac{3 x+1}{4} \\

\Rightarrow & 13 x>39 \text { and }-2 x+3<9 x+3

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & x>3 \text { and }-11 x<0 \\

\Rightarrow & x>3 \text { and } x>0 \\

\Rightarrow & x \in(3, \infty) \text { and } x \in(0, \infty) \Rightarrow x \in(3, \infty)

\end{array}

\)

Example 12: If \(-5 \leq \frac{2-3 x}{4} \leq 9\), then \(x=\) belongs to the interval

(a) \((-\infty, 22 / 3]\)

(b) \([-34 / 3,22 / 3]\)

(c) \([22 / 3, \infty)\)

(d) \((-\infty,-34 / 3]\)

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& -5 \leq \frac{2-3 x}{4} \leq 9 \\

\Rightarrow & -20 \leq 2-3 x \leq 36 \\

\Rightarrow & -22 \leq-3 x \leq 34 \\

\Rightarrow & -34 \leq 3 x \leq 22 \Rightarrow-\frac{34}{3} \leq x \leq \frac{22}{3} \Rightarrow x \in[-34 / 3,22 / 3]

\end{array}

\)

Generalized Method of Intervals for Solving Inequalities

Let \(F(x)=\left(x-a_1\right)^{k_1}\left(x-a_2\right)^{k_2} \ldots\left(x-a_{n-1}\right)^{k_{n-1}}\left(x-a_n\right)^{k_n}\)

where \(k_1, k_2, \ldots, k_n \in Z\) and \(a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n\) are fixed real numbers satisfying the condition

\(

a_1<a_2<a_3<\ldots<a_{n-1}<a_n

\)

For solving \(F(x)>0\) or \(F(x)<0\), consider the following algorithm:

- We mark the numbers \(a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n\) on the number axis and put the plus sign in the interval on the right of the largest of these numbers, i.e., on the right of \(a_n\).

- Then we put the plus sign in the interval on the left of \(a_n\) if \(k_n\) is an even number and the minus sign if \(k_n\) is an odd number. In the next interval, we put a sign according to the following rule:

- When passing through the point \(a_{n-1}\) the polynomial \(F(x)\) changes sign if \(k_{n-1}\) is an odd number. Then we consider the next interval and put a sign in it using the same rule.

- Thus we consider all the intervals. The solution of the inequality \(F(x)>0\) is the union of all intervals in which we have put the plus sign and the solution of the inequality \(F(x)<0\) is the union of all intervals in which we have put the minus sign.

Frequently used Inequalities

- \((x-a)(x-b)<0 \Rightarrow x \in(a, b)\), where \(a<b\)

- \((x-a)(x-b)>0 \Rightarrow x \in(-\infty, a) \cup(b, \infty)\), where \(a<b\)

- \(x^2 \leq a^2 \Rightarrow x \in[-a, a]\)

- \(x^2 \geq a^2 \Rightarrow x \in(-\infty,-a] \cup[a, \infty)\)

- If \(a x^2+b x+c<0,(a>0) \Rightarrow x \in(\alpha, \beta)\), where \(\alpha, \beta(\alpha<\beta)\) are roots of the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\)

- If \(a x^2+b x+c>0,(a>0) \Rightarrow x \in(-\infty, \alpha) \cup(\beta, \infty)\), where \(\alpha, \beta(\alpha<\beta)\) are roots of the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\)

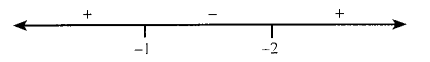

Example 13: Solve \(x^2-x-2>0\).

Solution: \(x^2-x-2>0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad(x-2)(x+1)>0

\)

Now \(x^2-x-2=0 \Rightarrow x=-1,2\).

Now on number line ( \(x\)-axis) mark \(x=-1\) and \(x=2\).

Now when \(x>2, x+1>0\) and \(x-2>0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad(x+1)(x-2)>0

\)

when \(-1<x<2, x+1>0\) but \(x-2<0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad(x+1)(x-2)<0

\)

when \(x<-1, x+1<0\) and \(x-2<0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad(x+1)(x-2)>0

\)

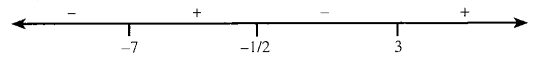

Hence, sign scheme of \(x^2-x-2\) is

From the figure, \(x^2-x-2>0, x \in(-\infty,-1) \cup(2, \infty)\).

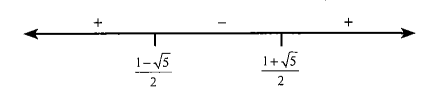

Example 14: Solve \(x^2-x-1<0\).

Solution: Let’s first factorize \(x^2-x-1\).

For that let \(x^2-x-1=0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x=\frac{1 \pm \sqrt{1+4}}{2}=\frac{1 \pm \sqrt{5}}{2}

\)

Now on number line ( \(x\)-axis) mark \(x=\frac{1 \pm \sqrt{5}}{2}\)

From the sign scheme of \(x^2-x-1\) which shown in the given figure,

\(

x^2-x-1<0 \Rightarrow x \in\left(\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}, \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)

\)

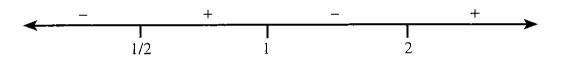

Example 15: Solve \((x-1)(x-2)(1-2 x)>0\).

Solution: We have \((x-1)(x-2)(1-2 x)>0\)

or \(\quad-(x-1)(x-2)(2 x-1)>0\)

or \(\quad(x-1)(x-2)(2 x-1)<0\)

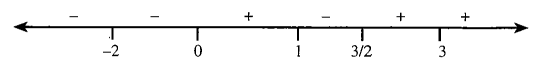

On number line mark \(x=1 / 2,1,2\)

When \(x>2\), all factors \((x-1) \cdot(2 x-1)\) and \((x-2)\) are positive.

Hence, \((x-1)(x-2)(2 x-1)>0\) for \(x>2\).

Now put positive and negative sign alternatively as shown in figure.

Hence, solution set of \((x-1)(x-2)(1-2 x)>0\) or \((x-1) (x-2)(2 x-1)<0\) is \((-\infty, 1 / 2) \cup(1,2)\).

Example 16: Solve \((2 x+1)(x-3)(x+7)<0\).

Solution: \(\quad(2 x+1)(x-3)(x+7)<0\)

Sign scheme of \((2 x+1)(x-3)(x+7)\) is as follows:

Hence, solution is \((-\infty,-7) \cup(-1 / 2,3)\).

Solving Rational Algebraic Inequalities

If \(P(x)\) and \(Q(x)\) are polynomials in \(x\), then the inequations \(\frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}>0, \frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}<0, \frac{P(x)}{Q(x)} \geq 0\), and \(\frac{P(x)}{Q(x)} \leq 0\) are known as rational algebraic inequations. To solve these inequations we use the sign method as explained in the following algorithm.

Algorithm:

- Step 1: Obtain \(P(x)\) and \(Q(x)\).

- Step 2: Factorise \(P(x)\) and \(Q(x)\) into linear factors.

- Step 3: Make the coefficient of \(x\) positive in all factors.

- Step 4: Obtain critical points by equating all factors to zero.

- Step 5: Plot the critical points on the number line. If there are \(n\) critical points, they divide the number line into ( \(n+1\) ) regions.

- Step 6: In the right most region the expression \(\frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}\) bears positive sign and in other regions the expression bears alternate negative and positive signs.

Example 17: If \(\frac{x-1}{x} \geq 2\), then \(x\) belongs to the interval

(a) \((1,2)\)

(b) \((0,1)\)

(c) \([-1,0)\)

(d) \((1, \infty)\)

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\frac{x-1}{x} \geq 2 \Rightarrow \frac{x-1}{x}-2 \geq 0 \Rightarrow \frac{-1-x}{x} \geq 0 \Rightarrow \frac{x+1}{x-0} \leq 0 \dots(i)

\)

The critical points are the values of \(x\) that make the numerator or the denominator of the expression equal to zero.

For the numerator, \(x+1=0 \Rightarrow x=-1\).

For the denominator, \(\boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{=} \mathbf{0}\).

The critical points are \(x=-1\) and \(x=0\). These points divide the number line into three intervals: \((-\infty,-1),(-1,0)\), and \((0, \infty)\).

Test intervals:

We need to check the sign of the expression \(\frac{x+1}{x}\) in each of the intervals.

Interval \((-\infty,-1)\) : Let’s pick a test value, for example, \(x=-2\). \(\frac{-2+1}{-2}=\frac{-1}{-2}=\frac{1}{2}\). Since \(\frac{1}{2}>0\), this interval does not satisfy the inequality \(\frac{x+1}{x} \leq 0\).

Interval \((-1,0)\) : Let’s pick a test value, for example, \(x=-0.5\). \(\frac{-0.5+1}{-0.5}=\frac{0.5}{-0.5}=-1\). Since \(-1<0\), this interval satisfies the inequality \(\frac{x+1}{x} \leq 0\).

Interval \((\mathbf{0}, \boldsymbol{\infty})\) : Let’s pick a test value, for example, \(\boldsymbol{x}=1\). \(\frac{1+1}{1}=\frac{2}{1}=2\). Since \(2>0\), this interval does not satisfy the inequality \(\frac{x+1}{x} \leq 0\).

The inequality is \(\frac{x+1}{x} \leq 0\). We found that the expression is negative in the interval ( \(-1,0\) ). We must also check the critical points.

For \(x=-1\), the numerator is zero, so the expression is \(\frac{-1+1}{-1}=\frac{0}{-1}=0\). Since \(0 \leq 0\) is true, \(x=-1\) is included in the solution.

For \(\boldsymbol{x}=\mathbf{0}\), the denominator is zero, so the expression is undefined. Therefore, \(\boldsymbol{x}=\mathbf{0}\) is not included in the solution.

The solution is the interval where the expression is negative or zero. This is \([-1,0)\)

Example 18: The set of all values of \(x\) satisfying the inequation \((x-1)^3(x+1)<0\) is

(a) \((-1,1)\)

(b) \((-\infty,-1)\)

(c) \([-1,1]\)

(d) \((-1, \infty)\)

Solution: (a) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (x-1)^3(x+1)<0 \\

\Rightarrow & (x-1)^2(x-1)(x+1)<0 \\

\Rightarrow & (x-1)(x+1)<0 \quad\left[\because(x-1)^2 \geq 0 \text { for all } x \in R\right] \\

\Rightarrow & -1<x<1 \Rightarrow x \in(-1,1)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 19: The solution set of \((5 x-1)<(x+1)^2<(7 x-3)\) is

(a) \((1,4)\)

(b) \([2,4]\)

(c) \((2,4)\)

(d) \((-\infty, 1) \cup(2, \infty)\)

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

(5 x-1)<(x+1)^2<(7 x-3) & \\

5 x-1<(x+1)^2 & \text { and }(x+1)^2<(7 x-3) \\

(x+1)^2-(5 x-1)>0 & \text { and }(x+1)^2-(7 x-3)<0 \\

x^2-3 x+2>0 & \text { and } x^2-5 x+4<0 \\

(x-1)(x-2)>0 & \text { and }(x-1)(x-4)<0 \\

x \in(-\infty, 1) \cup(2, \infty) & \text { and } x \in(1,4) \\

x \in(2,4) &

\end{array}

\)

Example 20: Solve \(\frac{2 x-3}{3 x-5} \geq 3\).

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{2 x-3}{3 x-5} \geq 3 \\

& \frac{2 x-3}{3 x-5}-3 \geq 0 \\

& \frac{2 x-3-9 x+15}{3 x-5} \geq 0 \\

& \frac{-7 x+12}{3 x-5} \geq 0 \\

& \frac{7 x-12}{3 x-5} \leq 0

\end{aligned}

\)

Sign scheme of \(\frac{7 x-12}{3 x-5}\) is as follows:

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x \in(5 / 3,12 / 7]

\)

\(x=5 / 3\) is not included in the solutions as at \(x=5 / 3\) denominator becomes zero.

Example 21: Solve \(x>\sqrt{(1-x)}\).

Solution: Given inequality can be solved by squaring both sides.

But sometimes squaring gives extraneous solutions which do not satisfy the original inequality. Before squaring we must restrict \(x\) for which terms in the given inequality are well defined.

\(x>\sqrt{(1-x)}\). Here \(x\) must be positive.

Here \(\sqrt{1-x}\) is defined only when \(1-x \geq 0\) or \(x \leq 1 \dots(1)\)

Squaring given inequality but sides \(x^2>1-x\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow x^2+x-1>0 \Rightarrow\left(x-\frac{-1-\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)\left(x-\frac{-1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)>0 \\

& \Rightarrow x<\frac{-1-\sqrt{5}}{2} \text { or } x>\frac{-1+\sqrt{5}}{2} \dots(2)

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\text { From (1) and (2) } x \in\left(\frac{\sqrt{5}-1}{2}, 1\right] \quad \text { (as } x \text { is }+\mathrm{ve} \text { ) }

\)

Example 22: Solve \(\frac{2}{x^2-x+1}-\frac{1}{x+1}-\frac{2 x-1}{x^3+1} \leq 0\).

Solution:

\(

\frac{2}{x^2-x+1}-\frac{1}{x+1}-\frac{2 x-1}{x^3+1} \geq 0

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{2(x+1)-\left(x^2-x+1\right)-(2 x-1)}{(x+1)\left(x^2-x+1\right)} \geq 0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{-\left(x^2-x-2\right)}{(x+1)\left(x^2-x+1\right)} \geq 0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{-(x-2)(x+1)}{(x+1)\left(x^2-x+1\right)} \geq 0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{2-x}{x^2-x+1} \geq 0, \text { where } x \neq 1 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 2-x \geq 0, x \neq-1,\left(\text { as } x^2-x+1>0 \text { for } \forall x \in \mathrm{R}\right) \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x \leq 2, x \neq-1

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 23: Solve \(x(x+2)^2(x-1)^5(2 x-3)(x-3)^4 \geq 0\).

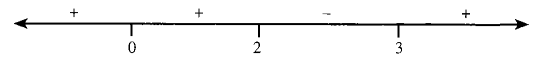

Solution: Sol. Let \(E=x(x+2)^2(x-1)^5(2 x-3)(x-3)^4\).

Here for \(x,(x-1),(2 x-3)\) exponents are odd, hence sign of \(E\) changes while crossing \(x=0,1,3 / 2\). Also for \((x+2)\), ( \(x-3\) ) exponents are even, hence sign of \(E\) does not change while crossing \(x=-2\) and \(x=3\).

Further for \(x>3\), all factors are positive, hence sign of the expression starts with positive sign from the right hand side.

The sign scheme of the expression is as shown in the following figure.

\text { Hence, for } E \geq 0 \text {, we have } x \in[0,1] \cup[3 / 2, \infty)

\)

Example 24: Solve \(x\left(2^x-1\right)\left(3^x-9\right)(x-3)<0\).

Solution: The critical points are the values of \(x\) where each factor equals zero.

\(x=0\)

\(2^x-1=0 \Longrightarrow 2^x=1 \Longrightarrow x=0\)

\(3^x-9=0 \Longrightarrow 3^x=9 \Longrightarrow x=2\)

\(x-3=0 \Longrightarrow x=3\)

The distinct critical points are \(\mathbf{0}, \mathbf{2}\), and \(\mathbf{3}\). These points divide the number line into the intervals \((-\infty, 0),(0,2),(2,3)\), and \((3, \infty)\).

\(

\begin{array}{llllll}

\hline

\text { Interval } & x & 2^x-1 & 3^x-9 & x-3 & \begin{array}{l}

\text { Product } \\

x\left(2^x-1\right)\left(3^x-9\right)(x-3)

\end{array} \\

\hline(-\infty, 0) & – & – & – & – & + \\

\hline(0, 2) & + & + & – & – & + \\

\hline(2, 3) & + & + & + & – & – \\

\hline(3, \infty) & + & + & + & + & + \\

\hline

\end{array}

\)

We are looking for the intervals where the product is negative. The product is negative only in the interval \((2,3)\).

Example 25: Find all possible values of \(\frac{x^2+1}{x^2-2}\).

Solution: Let \(y=\frac{x^2+1}{x^2-2}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad y x^2-2 y=x^2+1 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x^2=\frac{2 y+1}{y-1}

\end{aligned}

\)

Now \(x^2 \geq 0 \Rightarrow \frac{2 y+1}{y-1} \geq 0\)

Now \(x^2 \geq 0 \Rightarrow \frac{2 y+1}{y-1} \geq 0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad y \leq-1 / 2 \text { or } y>1

\)

Solving Irrational Inequalities

An irrational inequality is an inequality that contains at least one irrational expression, such as a variable under a square root, cube root, or other radical. To solve them, you typically isolate the irrational term, raise both sides to a power to eliminate the radical, and then solve the resulting inequality, remembering to check for extraneous solutions.

Example 26: Solve \(\sqrt{x-2} \geq-1\).

Solution: We must have \(x-2 \geq 0\) for \(\sqrt{x-2}\) to get defined, thus \(x \geq 2\).

Now \(\sqrt{x-2} \geq-1\), as square roots are always non-negative. Hence, \(x \geq 2\).

Note: Some students solve it by squaring it both sides for which \(x-2 \geq 1\) or \(x \geq 3\) which cause loss of interval \([2,3)\).

Example 27: Solve \(\sqrt{x-1}>\sqrt{3-x}\).

Solution: \(\sqrt{x-1}>\sqrt{3-x}\) is meaningful if \(x-1 \geq 0\) and \(3-x \geq 0\)

\(

1 \leq x \leq 3 \dots(1)

\)

Also \(\quad \sqrt{x-1}>\sqrt{3-x}\)

Squaring, we have \(x-1>3-x\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x>2 \dots(2)

\)

From (1) and (2), we have \(2<x \leq 3\).

Example 28: Solve \(\boldsymbol{x}+\sqrt{\boldsymbol{x}} \geq \sqrt{\boldsymbol{x}}-\mathbf{3}\).

Solution: \(x+\sqrt{x} \geq \sqrt{x}-3\) is meaningful only when \(x \geq 0 \dots(1)\)

Now \(x+\sqrt{x} \geq \sqrt{x}-3\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x \geq-3 \dots(2)

\)

From (1) and (2), we have \(x \geq 0\).

Example 29: Solve \(\left(x^2-4\right) \sqrt{x^2-1}<0\).

Solution: \(\left(x^2-4\right) \sqrt{x^2-1}<0\)

We must have \(x^2-1 \geq 0\)

or \(\quad(x-1)(x+1) \geq 0\)

or \(\quad x \leq-1\) or \(x \geq 1\)

Also \(\left(x^2-4\right) \sqrt{x^2-1}<0 \dots(1)\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x^2-4<0

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\Rightarrow \quad-2<x<2 \dots(2)\\

&\text { From (1) and (2), we have } x \in(-2,-1] \cup[1,2)

\end{aligned}

\)

Absolute Value of \(\boldsymbol{x}\)

Absolute value of any real number \(x\) is denoted by \(|x|\) (read as modulus of \(x\) ).

\(

\text { Thus }|x|= \begin{cases}x, & x \geq 0 \\ -x, & x<0\end{cases}

\)

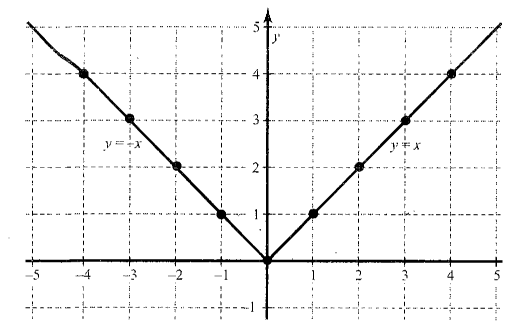

Graph of function \(f(x)=y=|x|\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Graph of function } f(x)=y=|x|\\

&\begin{array}{|c|c|c|c|c|}

\hline x & 0 & \pm 1 & \pm 2 & \pm 3 \\

\hline y & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 \\

\hline

\end{array}

\end{aligned}

\)

We can see that graph of \(y=|x|\) is in \(1^{\text {st }}\) and \(2^{\text {nd }}\) quadrant only where \(y \geq 0\), hence \(|x| \geq 0\).

Some Useful Results

Following are some useful results:

- \(|x|<a \Leftrightarrow-a<x<a\) i.e. \(x \in(-a, a)\)

- \(|x| \leq a \Leftrightarrow-a \leq x \leq a\) i.e. \(x \in[-a, a]\)

- \(|x|>a \Leftrightarrow x<-a\) or \(x>a\) i.e. \(x \in(-\infty,-a) \cup(a, \infty)\)

- \(|x| \geq a \Leftrightarrow x \leq-a\) or \(x \geq a\) i.e. \(x \in(-\infty,-a] \cup[a, \infty)\)

If \(r\) is a positive real number and \(a\) is any real number, then

- \(|x-a|<r \Leftrightarrow a-r<x<a+r\) i.e. \(x \in(a-r, a+r)\)

- \(|x-a| \leq r \Leftrightarrow a-r \leq x \leq a+r\) i.e. \(x \in[a-r, a+r]\)

- \(|x-a|>r \Leftrightarrow x<a-r\) or, \(x>a+r\)

\(

\text { i.e. } x \in(-\infty, a-r) \cup(a+r, \infty)

\) - \(|x-a| \geq r \Leftrightarrow x \leq a-r\) or, \(x \geq a+r\)

\(

\text { i.e. } x \in(-\infty, a-r] \cup[a+r, \infty)

\)

If \(a, b>0\) and \(c\) are real numbers, then - \(a<|x|<b \Leftrightarrow x \in(-b,-a) \cup(a, b)\)

- \(a \leq|x| \leq b \Leftrightarrow x \in[-b,-a] \cup[a, b]\)

- \(a \leq|x-c| \leq b \Leftrightarrow x \in[-b+c,-a+c] \cup[a+c, b+c]\)

- \(a<|x-c|<b \Leftrightarrow x \in(-b+c,-a+c) \cup(a+c, b+c)\)

- If \(a, b, c \in R\) such that \(b^2-4 a c<0\), then

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a>0 \Rightarrow a x^2+b x+c>0 \text { for all } x \in R \\

& a<0 \Rightarrow a x^2+b x+c<0 \text { for all } x \in R

\end{aligned}

\)

i.e. \(a x^2+b x+c\) and \(a\) are of the same sign for all \(x \in R\).

Example 30: Solve the following: \(x^2-|x|-2=0\)

Solution:

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& x^2-|x|-2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & |x|^2-|x|-2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (|x|-2)(|x|+1)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & |x|=2(\because|x|+1 \neq 0) \\

\Rightarrow & x= \pm 2

\end{array}

\)

Example 31: Find the value of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) for which following expressions are defined:

(i) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{x-|x|}}\)

(ii) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{x+|x|}}\)

Solution:

(i) \(x-|x|=\left\{\begin{array}{c}x-x=0, \text { if } x \geq 0 \\ x+x=2 x, \text { if } x<0\end{array}\right.\)

\(

\Rightarrow x-|x| \leq 0 \text { for all } x

\)

\(\Rightarrow \frac{1}{\sqrt{x-|x|}}\) does not take real values for any \(x \in R\)

\(\Rightarrow \frac{1}{\sqrt{x-|x|}}\) is not defined for any \(x \in R\).

(ii)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x+|x|=\left\{\begin{array}{c}

x+x=2 x, \text { if } x \geq 0 \\

x-x=0, \text { if } x<0

\end{array}\right. \\

& \quad \Rightarrow \frac{1}{\sqrt{x+|x|}} \text { is defined only when } x>0

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 32: Solve the following: \(2|x+1|^2-|x+1|=3\)

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 2|x+1|^2-|x+1|=3 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 2|x+1|^2-|x+1|-3=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 2|x+1|^2-3|x+1|+2|x+1|-3=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(2|x+1|-3)(|x+1|+1)=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 2|x+1|-3=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad|x+1|=3 / 2 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x+1= \pm 3 / 2 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x=1 / 2 \text { or } x=-5 / 2

\end{aligned}

\)

Note:

\(

|x-a|=\left\{\begin{array}{l}

x-a, x \geq a \\

a-x, x<a

\end{array}, \text { where } a>0\right.

\)

In general, \(|f(x)|=\left\{\begin{array}{c}f(x), f(x) \geq 0 \\ -f(x), f(x)<0\end{array}\right.\), where \(y=f(x)\) is any real-valued function.

Example 33: Solve \(1-x=\sqrt{x^2-2 x+1}\).

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 1-x=\sqrt{x^2-2 x+1} \\

\Rightarrow & 1-x=\sqrt{(x-1)^2} \\

\Rightarrow & 1-x=|x-1| \\

\Rightarrow & 1-x \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & x \leq 1

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 34: Solve \(\sqrt{x+3-4 \sqrt{x-1}}+\sqrt{x+8-6 \sqrt{x-1}}=1\)

Solution: \(\sqrt{x+3-4 \sqrt{x-1}}+\sqrt{x+8-6 \sqrt{x-1}}=1\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \sqrt{x-1-4 \sqrt{x-1}+4}+\sqrt{x-1-6 \sqrt{x-1}+9}=1 \\

& \Rightarrow \sqrt{|\sqrt{x-1}-2|^2}+\sqrt{|\sqrt{x-1}-3|^2}=1 \\

& \Rightarrow|\sqrt{x-1}-2|+|\sqrt{x-1}-3|=1

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad|\sqrt{x-1}-2|+|\sqrt{x-1}-3|=(\sqrt{x-1}-2)-(\sqrt{x-1}-3) \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \sqrt{x-1}-2 \geq 0 \text { and } \sqrt{x-1}-3 \leq 0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 2 \leq \sqrt{x-1} \leq 3 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 4 \leq x-1 \leq 9 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 5 \leq x \leq 10

\end{aligned}

\)

Equations reducible to Quadratic

Example 35: Solve \(\sqrt{5 x^2-6 x+8}-\sqrt{5 x^2-6 x-7}=1\).

Solution: Let \(5 x^2-6 x=y\). Then,

\(

\sqrt{5 x^2-6 x+8}-\sqrt{5 x^2-6 x-7}=1

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \sqrt{y+8}-\sqrt{y-7}=1 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(\sqrt{y+8}-\sqrt{y-7})^2=1 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad y=\sqrt{y^2+y-56} \\

& \Rightarrow y^2=y^2+y-56 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad y=56 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 5 x^2-6 x=56 \left[\because y=5 x^2-6 x\right] \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 5 x^2-6 x-56=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(5 x+14)(x-4)=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x=4, \frac{-14}{5}

\end{aligned}

\)

Clearly, both the values satisfy the given equation. Hence, the roots of the given equation are 4 and \(-14 / 5\).

Example 36: Solve the equation \(4^x-5 \times 2^x+4=0\).

Solution: We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 4^x-5 \times 2^x+4=0 \\

\Rightarrow & \left(2^x\right)^2-5\left(2^x\right)+4=0 \\

\Rightarrow & y^2-5 y+4=0, \text { where } y=2^x \\

\Rightarrow & (y-4)(y-1)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & y=1,4 \\

\Rightarrow & 2^x=1,2^x=4 \\

\Rightarrow & 2^x=2^0, 2^x=2^2 \\

\Rightarrow & x=0,2

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the roots of the given equation are 0 and 2.

Example 37: Solve the equation \(3^{x^2-x}+4^{x^2-x}=25\).

Solution: We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 3^{x^2-x}+4^{x^2-x}=25 \\

\Rightarrow & 3^{x^2-x}+4^{x^2-x}=3^2+4^2 \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-x=2 \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-x-2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (x-2)(x+1)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & x=-1,2

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the roots of the given equation are -1 and 2.

Example 38: Evaluate \(\sqrt{6+\sqrt{6+\sqrt{6+\cdots \infty}}}\).

Solution: Let \(x=\sqrt{6+\sqrt{6+\sqrt{6+\cdots \infty}}}\). Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=\sqrt{6+x} \\

\Rightarrow & x^2=6+x \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-x-6=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (x-3)(x+2)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & x=3 \text { or } x=-2

\end{aligned}

\)

But, the given expression is positive. So, \(x=3\). Hence, the value of the given expression is 3.

Solution Of Linear Inequalities in two variables

In order to represent the solution set of a linear inequation in two variables, we may follow the following algorithm.

Algorithm:

- STEP I: Convert the given inequation, say \(a x+b y \leq c\), into the equation \(ax + by =c\) which represents a straight line in \(x y\)-plane.

- STEP II: Put \(y=0\) in the equation obtained in step I to get the point where the line meets with \(x\)-axis. Similarly, put \(x=0\) to obtain a point where the line meets with \(y\)-axis.

- STEP III: Join the points obtained in step II to obtain the graph of the line obtained from the given inequation. In case of a strict inequality i.e. \(a x+b y<c\) or \(a x+b y>c\), draw the dotted line, otherwise mark it thick line.

- STEP IV: Choose a point, if possible ( 0,0 ), not lying on this line : Substitute its coordinates in the inequation. If the inequation is satisfied, then shade the portion of the plane which contains the chosen point; otherwise shade the portion which does not contain the chosen point.

- STEP V: The shaded region obtained in step IV represents the desired solution set.

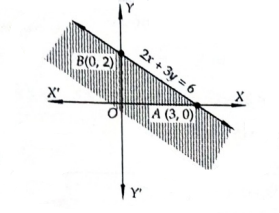

For example, to represent the solution set of the inequation \(2 x+3 y \leq 6\), we first draw the line \(2 x+3 y=6\). This line divides the \(x y\)-plane in two parts. To determine the region represented by the given inequation, we take a point in one of the regions. Let the point be \(O(0,0)\). Clearly, \((0,0)\) satisfies the inequation. So, the region containing the origin is represented by the given inequation as shown in Figure below.

In order to determine the region represented by a system of simultaneous linear inequations, we find the intersection of regions represented by all inequations.

Example 39: The set of all real numbers \(x\) for which [IIT (s) 2002]

\(

x^2-|x+2|+x>0 \text {, is }

\)

(a) \((-\infty,-2) \cup(2, \infty)\)

(b) \((-\infty,-\sqrt{2}) \cup(\sqrt{2}, \infty)\)

(c) \((-\infty,-1) \cup(1, \infty)\)

(d) \((\sqrt{2}, \infty)\)

Solution: (b) CASE I: When \(x+2 \geq 0\)

In this case, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& |x+2|=x+2 \\

\therefore & x^2-|x+2|+x>0 \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-(x+2)+x>0 \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-2>0 \\

\Rightarrow & x<-\sqrt{2} \text { or } x>\sqrt{2} \Rightarrow x \in(-\infty,-\sqrt{2}) \cup(\sqrt{2}, \infty)

\end{aligned}

\)

But, \(x+2 \geq 0\) i.e. \(x \geq-2\)

\(

\therefore \quad x \in[-2,-\sqrt{2}) \cup(\sqrt{2}, \infty)

\)

CASE II: When \(x+2<0\)

In this case, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& |x+2|=-(x+2) \\

\therefore \quad & x^2-|x+2|+x>0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & x^2+x+2+x>0 \Rightarrow x^2+2 x+2>0

\end{aligned}

\)

This is true for all real values of \(x\) as the discriminant of \(x^2+2 x+2\) is less than zero.

So, \(x+2<0\) i.e. \(x \in(-\infty,-2)\) is the solution set.

Hence, the solution set is

\(

[-2,-\sqrt{2}) \cup(\sqrt{2}, \infty) \cup(-\infty,-2) \text { or, }(-\infty,-\sqrt{2}) \cup(\sqrt{2}, \infty) \text {. }

\)

Example 40: The set of values of \(x\) for which the inequality \(|x-1|+|x+1|<4\) always holds true, is [JEE (Orissa) 2002]

(a) \((-2,2)\)

(b) \((-\infty,-2) \cup(2, \infty)\)

(c) \((-\infty,-1] \cup[1, \infty)\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (a) On the LHS of the given inequation there are two terms \(|x-1|\) and \(|x+1|\). On equating \(x-1\) and \(x+1\) to zero, we get \(x=-1,1\) as critical points. These points divide the real line into three regions viz. \((-\infty,-1),[-1,1]\) and \((1, \infty)\).

So, we consider the following cases:

CASE I: When \(-\infty<x<-1\)

In this case, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& |x-1|=-(x-1) \text { and }|x+1|=-(x+1) \\

\therefore & |x-1|+|x+1|<4 \\

\Rightarrow & -(x-1)-(x+1)<4 \Rightarrow-2 x<4 \Rightarrow x>-2

\end{aligned}

\)

But, \(-\infty<x<-1\)

\(

\therefore \quad x \in(-2,-1)

\)

CASE II: When \(-1 \leq x<1\)

In this case, we have

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& |x-1|=-(x-1) \text { and }|x+1|=x+1 \\

\therefore & |x-1|+|x+1|<4 \\

\Rightarrow & -(x-1)+x+1<4 \\

\Rightarrow & 2<4, \text { which is true for all } x \in[-1,1) . \\

\therefore & x \in[-1,1)

\end{array}

\)

CASE III: When \(1 \leq x<\infty\)

In this case, we have

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& |x-1|=x-1 \text { and }|x+1|=x+1 \\

\therefore & |x-1|+|x+1|<4 \\

\Rightarrow & x-1+x+1<4 \Rightarrow x<2

\end{array}

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x \in[1,2) \quad[\because 1<x<\infty]

\)

\(

\text { Hence, } x \in(-2,-1) \cup[-1,1) \cup[1,2) \text { or, } x \in(-2,2) \text {. }

\)

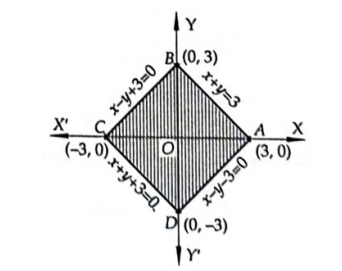

Example 41: The area of the region represented by \(|x-y| \leq 3\) and \(|x+y| \leq 3\), is

(a) 36 sq. units

(b) 18 sq. units

(c) 72 sq. units

(d) 6 sq. units

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& |x-y| \leq 3 \text { and }|x+y| \leq 3 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & -3 \leq x-y \leq 3 \text { and }-3 \leq x+y \leq 3 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & (x-y-3 \leq 0, x-y+3 \geq 0)

\end{array}

\)

and,

\(

(x+y-3 \leq 0 \text { and } x+y+3 \geq 0)

\)

The shaded region in Figure below is the region represented by these four in equations.

\(\therefore \quad\) Required area \(=\) Area of the square \(A B C D=18\) sq.units.

Note: Alternatively, the area can be calculated using the formula for a rhombus (which a square is) as half the product of its diagonals.

Some Inequalities

Theorem 1: (Arithmetic-geometric Mean Inequality): If \(a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n\) are \(n\) distinct positive real numbers, then

\(

\frac{a_1+a_2+\ldots \ldots+a_n}{n}>\left(a_1 a_2 \ldots . . a_n\right)^{1 / n}

\)

i.e. A.M. > G.M.

Remark 1: If \(a_1=a_2=\ldots=a_n\), then A.M. \(=\) G.M.

Particular Cases: For \(n=2\) and 3 the above inequality becomes

\(

\frac{a_1+a_2}{2}>\sqrt{a_1 a_2}, \frac{a_1+a_2+a_3}{3}>\sqrt[3]{a_1 a_2 a_3}

\)

Remark 2: If \(a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n\) are \(n\) distinct positive real numbers, then \(H=\frac{n}{\frac{1}{a_1}+\frac{1}{a_2}+\ldots .+\frac{1}{a_n}}\) is called the harmonic mean of \(a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n\) and, we have

\(

\text { A.M. }>\text { G.M. }>\text { H.M. }

\)

Also, A.M. \(=\) G.M. \(=\) H.M. iff \(a_1=a_2=\ldots=a_n\).

Thus, in general, we have

\(

\text { A.M. } \geq \text { G.M. } \geq \text { H.M. }

\)

Example 42: If \(-\frac{\pi}{2}<\theta<\frac{\pi}{2}\), then the minimum value of \(\cos ^3 \theta+\sec ^3 \theta\) is

(a) 1

(b) 2

(c) 0

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) We know that

A.M. \(\geq\) G.M.

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \therefore \quad \frac{\cos ^3 \theta+\sec ^3 \theta}{2} \geq \sqrt{\cos ^3 \theta \times \sec ^3 \theta} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \cos ^3 \theta+\sec ^3 \theta \geq 2 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the minimum value of \(\cos ^3 \theta+\sec ^3 \theta\) is 2.

Example 43: If \(a>1, b>1\), then the minimum value of \(\log _b a+\log _a b\) is

(a) 0

(b) 1

(c) 2

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) Using A.M. \(\geq\) G.M., we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{\log _b a+\log _a b}{2} \geq \sqrt{\log _b a+\log _a b} \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \log _b a+\log _a b \geq 2

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the minimum value of \(\log _b a+\log _a b\) is 2 and it is attained when \(a=b\).

Example 44: The minimum value of \(9^x+9^{1-x}, x \in R\), is

(a) 2

(b) 3

(c) 4

(d) none of these

Solution: (d) Using A.M. \(\geq\) G.M., we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{9^x+9^{1-x}}{2} \geq \sqrt{9^x \times 9^{1-x}} \\

\Rightarrow \quad & 9^x+9^{1-x} \geq 6

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the least value of \(9^x+9^{1-x}\) is 6.

Example 45: If \(a, b, c\) are three non-zero numbers of the same sign, then the value of \(\frac{a}{b}+\frac{b}{c}+\frac{c}{a}\) lies in the interval

(a) \([2, \infty)\)

(b) \([3, \infty)\)

(c) \((3, \infty)\)

(d) \((-\infty, 3)\).

Solution: (b) Since \(a, b, c\) are of the same sign. Therefore, \(\frac{a}{b}, \frac{b}{c}, \frac{c}{a}\) are positive real numbers.

Now, A.M. \(\geq\) G.M.

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{1}{3}\left(\frac{a}{b}+\frac{b}{c}+\frac{c}{a}\right) \geq\left(\frac{a}{b} \times \frac{b}{c} \times \frac{c}{a}\right)^{1 / 3} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{a}{b}+\frac{b}{c}+\frac{c}{a} \geq 3 \Rightarrow \frac{a}{b}+\frac{b}{c}+\frac{c}{a} \in[3, \infty)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 46: If \(a, b\) are positive real numbers such that \(a b=1\), then the least value of the expression \((1+a)(1+b)\) is

(a) 2

(b) 3

(c) 4

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) We have, \(a b=1 \Rightarrow b=\frac{1}{a}\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & (1+a)(1+b)=(1+a)\left(1+\frac{1}{a}\right) \\

\Rightarrow & (1+a)\left(1+\frac{1}{a}\right)=2+a+\frac{1}{a} \geq 2+2=4 \quad\left[\because a+\frac{1}{a} \geq 2\right]

\end{array}

\)

Hence, the least value of \((1+a)(1+b)\) is 4.

Example 47: If \(a=\log _5 3+\log _7 5+\log _9 7\), then

(a) \(a \in[3 / 2, \infty)\)

(b).\(a \in\left[\frac{1}{2^{1 / 3}}, \infty\right)\)

(c) \(a \in\left[\frac{3}{2^{1 / 3}}, \infty\right)\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) Using A.M. \(\geq\) G.M., we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{a}{3}=\frac{\log _5 3+\log _7 5+\log _9 7}{3} \geq\left(\log _5 3 \times \log _7 5 \times \log _9 7\right)^{1 / 3} \\

\Rightarrow & a \geq 3\left(\log _9 3\right)^{1 / 3} \Rightarrow a \geq 3\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{1 / 3} \Rightarrow a \in\left[\frac{3}{2^{1 / 3}}, \infty\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 48: If \(a, b, c\) are distinct positive real numbers, then

(a) \(a^2+b^2+c^2>a b+b c+c a\)

(b) \(a^2+b^2+c^2<a b+b c+c a\)

(c) \(a^2+b^2+c^2 \geq a b+b c+c a\)

(d) \(a^2+b^2+c^2 \leq a b+b c+c a\)

Solution: (a) Using A.M. > G.M., we have

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & \frac{a^2+b^2}{2}>\sqrt{a^2 b^2} \\

\Rightarrow & a^2+b^2>2 a b \dots(i)

\end{array}

\)

Similarly, we have

\(

b^2+c^2>2 b c \dots(ii)

\)

and, \(c^2+a^2>2 c a \dots(iii)\)

Adding all these, we get

\(

\begin{aligned}

& & 2\left(a^2+b^2+c^2\right) & >2(a b+b c+c a) \\

\Rightarrow & & a^2+b^2+c^2 & >a b+b c+c a

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 49: If \(a, b, c\) are three distinct positive real numbers such that

\(\frac{b+c}{a}+\frac{c+a}{b}+\frac{a+b}{c}>k\), then the greatest value of \(k\) is

(a) 6

(b) 3

(c) 4

(d) 9

Solution: (a) Using, A.M. > G.M. we have

\(

\therefore \quad \frac{\frac{a}{b}+\frac{b}{a}}{2}>\sqrt{\frac{a}{b} \times \frac{b}{a}} \Rightarrow \frac{a}{b}+\frac{b}{a}>2 \dots(i)

\)

Similarly, we have

\(

\frac{a}{c}+\frac{c}{a}>2 \text { and, } \frac{b}{c}+\frac{c}{a}>2

\)

Adding these three, we get

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(\frac{a}{b}+\frac{b}{a}\right)+\left(\frac{b}{c}+\frac{c}{b}\right)+\left(\frac{a}{c}+\frac{c}{a}\right)>2+2+2 \\

\Rightarrow & \left(\frac{a}{b}+\frac{c}{b}\right)+\left(\frac{b}{a}+\frac{c}{a}\right)+\left(\frac{b}{c}+\frac{a}{c}\right)>6 \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{a+c}{b}+\frac{b+c}{a}+\frac{a+b}{c}>6 \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{b+c}{a}+\frac{c+a}{b}+\frac{a+b}{c}>6

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the greatest value of \(k\) is 6.

Example 50: If \(a^2+b^2+c^2=1\), then \(a b+b c+c a\) lies in the interval [AIEEE 2002]

(a) \([0,1]\)

(b) \([-1 / 2,1]\)

(c) \([0,1 / 2]\)

(d) \([1,2]\)

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

a^2+b^2+c^2-a b-b c-c a=\frac{1}{2}\left[(a-b)^2+(b-c)^2+(c-a)^2\right] \geq 0

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad a^2+b^2+c^2 \geq a b+b c+c a \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 1 \geq a b+b c+c a \left[\because a^2+b^2+c^2=1\right]\\

& \Rightarrow \quad a b+b c+c a \leq 1 \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Also, }\\

&\begin{aligned}

& (a+b+c)^2 \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & a^2+b^2+c^2+2(a b+b c+c a) \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & 1+2(a b+b c+c a) \geq 0

\end{aligned} \quad\left[\because a^2+b^2+c^2=1\right]

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\Rightarrow \quad a b+b c+c a \geq-\frac{1}{2} \dots(ii)\\

&\text { From (i) and (ii), we obtain }\\

&-\frac{1}{2} \leq a b+b c+c a \leq 1 \Rightarrow a b+b c+c a \in[-1 / 2,1] .

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 51: If \(a, b, c\) are positive real numbers, then the least value of \((a+b+c)\left(\frac{1}{a}+\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c}\right)\), is [JEE (Orissa) 2002]

(a) 9

(b) 3

(c) \(\frac{10}{3}\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (a) Using A.M. \(\geq\) G.M., we have

\(

\frac{a+b+c}{3} \geq(a b c)^{1 / 3}

\)

and,

\(

\frac{1}{3}\left(\frac{1}{a}+\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c}\right) \geq\left(\frac{1}{a b c}\right)^{1 / 2}

\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & \frac{a+b+c}{3} \times \frac{1}{3}\left(\frac{1}{a}+\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c}\right) \geq 1 \\

\Rightarrow & (a+b+c)\left(\frac{1}{a}+\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c}\right) \geq 9

\end{array}

\)

Hence, the least value of \((a+b+c)\left(\frac{1}{a}+\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c}\right)\) is 9 and it attains

this value when \(a=b=c=1\) this value when \(a=b=c=1\).

Example 52: If \(a, b, c, d\) are positive real numbers such that \(a+b+c+d=2\), then \(M=(a+b)(c+d)\) satisfies the relation [IIT (S) 2000]

(a) \(0 \leq M \leq 1\)

(b) \(1 \leq M \leq 2\)

(c) \(2 \leq M \leq 3\)

(d) \(3 \leq M \leq 4\)

Solution: (a) Using A.M. \(\geq\) G.M., we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{(a+b)+(c+d)}{2} \geq\{(a+b)(c+d)\}^{1 / 2} \\

\Rightarrow & \quad \frac{2}{2} \geq M^{\frac{1}{2}} \\

\Rightarrow & M \leq 1

\end{aligned}

\)

As \(a, b, c, d>0\). Therefore, \(M=(a+b)(c+d)>0\). Hence, \(0 \leq M \leq 1\).

Example 53: If \(a_1, a_2, a_3, \ldots, a_n\) are positive real numbers whose product is a fixed number \(c\), then the minimum value of \(a_1+a_2+\ldots+2 a_n\), is [IIT (S) 2002]

(a) \(n(2 c)^{1 / n}\)

(b) \((n+1) c^{1 / n}\)

(c) \(2 n c^{1 / n}\)

(d) \((n+1)(2 c)^{1 / n}\)

Solution: (a) Using A.M. \(\geq\) G.M., we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{a_1+a_2+\ldots+a_{n-1}+2 a_n}{n} \geq\left(a_1 a_2 \ldots . .2 a_n\right)^{1 / n} \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \frac{a_1+a_2+\ldots+a_{n-1}+2 a_n}{n} \geq(2 c)^{1 / n} \quad\left[\because a_1 a_2 \ldots . a_n=c\right] \\

\Rightarrow \quad & a_1+a_2+\ldots .+a_{n-1}+2 a_n>n(2 c)^{1 / n}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 54: If \(\alpha \in(0, \pi / 2)\) then \(\sqrt{x^2+x}+\frac{\tan ^2 \alpha}{\sqrt{x^2+x}}\) is always greater than or equal to [IIT (S) 2003]

(a) \(2 \tan \alpha\)

(b) 1

(c) 2

(d) \(\sec ^2 \alpha\)

Solution: (a) Using A.M. \(\geq\) G.M., we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{1}{2}\left\{\sqrt{x^2+x}+\frac{\tan ^2 \alpha}{\sqrt{x^2+x}}\right\} \geq \sqrt{\sqrt{x^2+x}} \times \frac{\tan ^2 \alpha}{\sqrt{x^2+x}} \\

\Rightarrow & \sqrt{x^2+x}+\frac{\tan ^2 \alpha}{\sqrt{x^2+x}} \geq 2 \tan \alpha

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 55: If \(a, b, c\) are sides of a triangle, then \(\frac{(a+b+c)^2}{a b+b c+c a}\) altuays belongs to [CEE (Delhi) 2009]

(a) \([1,2]\)

(b) \([2,3]\)

(c) \([3,4]\)

(d) \([4,5]\)

Solution: (c) Using A.M. \(\geq\) G.M., we have

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& \frac{a^2+b^2}{2} \geq a b, \frac{b^2+c^2}{2} \geq b c \text { and } \frac{c^2+a^2}{2} \geq c a \\

\Rightarrow & a^2+b^2>2 a b, b^2+c^2 \geq 2 b c \text { and } c^2+a^2 \geq 2 c a \\

\Rightarrow & a^2+b^2+c^2 \geq a b+b c+c a \\

\Rightarrow & (a+b+c)^2 \geq 3(a b+b c+c a) \Rightarrow \frac{(a+b+c)^2}{a b+b c+c a} \geq 3

\end{array}

\)

Since \(a, b, c\) represent the sides of a triangle.

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \therefore \quad|a-b| \leq c,|b-c| \leq a \text { and }|c-a| \leq b \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a^2+b^2-2 a b \leq c^2, b^2+c^2-2 b c \leq a^2 \text { and } c^2+a^2-2 c a \leq b^2 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a^2+b^2+c^2 \leq 2(a b+b c+c a) \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(a+b+c)^2 \leq 4(a b+b c+c a) \Rightarrow \frac{(a+b+c)^2}{a b+b c+c a} \leq 4

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, \(\frac{(a+b+c)^2}{a b+b c+c a} \in[3,4]\)

Example 56: The minimum value of the sum of real numbers \(a^{-5}, a^{-4}, 3 a^{-3}, 1, a^8\) and \(a^{10}\) with \(a>0\) is [IIT 2011]

(a) 6

(b) 7

(c) 8

(d) 9

Solution: (c) Using \(A M \geq G M\), we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{a^{-5}+a^{-4}+a^{-3}+a^{-3}+a^{-3}+1+a^8+a^{10}}{8} \\

& \quad \geq\left(a^{-5} \times a^{-4} \times a^{-3} \times a^{-3} \times a^{-3} \times 1 \times a^8 \times a^{10}\right)^{1 / 8}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & \frac{a^{-5}+a^{-4}+3 a^{-3}+1+a^8+a^{10}}{8} \geq 1 \\

\Rightarrow & a^{-5}+a^{-4}+3 a^{-3}+1+a^8+a^{10} \geq 8

\end{array}

\)

Hence, the minimum value of \(a^{-5}+a^{-4}+3 a^{-3}+1+a^8+a^{10}\) is 8.