5.9 Entrance Corner (Complex Numbers)

Representation Of Complex Numbers

A complex number can be represented in the following forms:

- Geometrical form

- Vectorial form

- Trigonometrical form or Polar form.

- Eulerian form

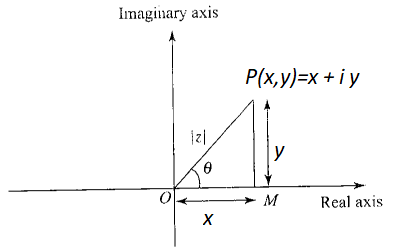

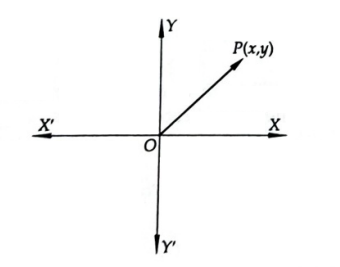

Geometrical form a Complex Number

A complex number \(z=x+i y\) can be represented by a point ( \(x, y\) ) on the plane which is known as the Argand plane. The point \(P(x, y)\) represents the complex number \(z=x+i y\).

If a complex number is purely real, then its imaginary part is zero. Therefore, a purely real number is represented by a point on \(x\)-axis. A purely imaginary complex number is represented by a point on \(y\)-axis. That is why \(x\)-axis is known as the real axis and \(y\)-axis, as the imaginary axis.

The plane in which we represent a complex number geometrically is known as the complex plane or Argand plane or the Gaussian plane. The point \(P\), plotted on the Argand plane, is called the Argand diagram.

The length of the line segment \(O P\) is called the modulus of \(z\) and is denoted by \(|z|\).

From Figure below,

we have

\(

O P^2=O M^2+M P^2 \Rightarrow O P^2=x^2+y^2 \Rightarrow O P=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}

\)

Thus,

\(

|z|=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}=\sqrt{\{\operatorname{Re}(z)\}^2+\{\operatorname{Im}(z)\}^2}

\)

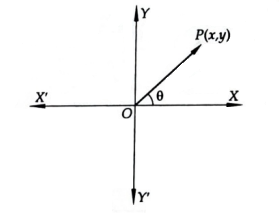

The angle \(\theta\) which \(O P\) makes with positive direction of \(x\)-axis in anticlockwise sense is called the argument or amplitude of \(z\) and is denoted by \(\arg (z)\) or, \(\operatorname{amp}(z)\).

In Figure below, we have

\(

\tan \theta=\frac{P M}{O M}=\frac{y}{x}=\frac{\operatorname{Im}(z)}{\operatorname{Re}(z)} \Rightarrow \theta=\tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{\operatorname{Im}(z)}{\operatorname{Re}(z)}\right)

\)

This angle \(\theta\) has infinitely many values differing by multiples of \(2 \pi\). The unique value of \(\theta\) such that \(-\pi<\theta \leq \pi\) is called the principal value of the amplitude or principal argument.

This formula for determining the argument of \(z=x+i y\) has severe drawback, because \(z_1=1+i \sqrt{3}\) and \(z_2=-1-i \sqrt{3}\) are two distinct complex numbers represented by two distinct points in the Argand plane but their arguments seem to be \(\tan ^{-1} \sqrt{3}=\pi / 3\) or, \(4 \pi / 3\) which is not correct. In fact, the argument is the common solution of the simultaneous trigonometric equations

\(

\cos \theta=\frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}} \text { and } \sin \theta=\frac{y}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}

\)

Since the above system of equations has infinitely many solutions, therefore there can be infinitely many arguments of \(z=x+i y\). The argument \(\theta\) which satisfies the inequality \(-\pi<\theta \leq \pi\) is usually known as the principal argument of \(z\).

Following algorithm may be used to find the argument of a complex number.

Algorithm:

- Step I: Find the value of \(\tan ^{-1}\left|\begin{array}{l}y \\ x\end{array}\right|\) lying between 0 and \(\pi / 2\). Let it be \(\alpha\).

- Step II: Determine in which quadrant the point \(P(x, y)\) belongs. If \(P(x, y)\) belongs to the first quadrant, then \(\arg (z)=\alpha\).

If \(P(x, y)\) belongs to the second quadrant, then \(\arg (z)=\pi-\alpha\)

If \(P(x, y)\) lies in the third quadrant, then \(\arg (z)=\pi+\alpha\).

If \(P(x, y)\) belongs to the fourth quadrant, then \(\arg (z)=-\alpha\) or, \(2 \pi-\alpha\).

Example 1: The principal argument of \(z=\frac{\sqrt{3}+i}{\sqrt{3}-i}\) is

(a) \(-\frac{\pi}{3}\)

(b) \(\frac{\pi}{3}\)

(c) \(\frac{\pi}{6}\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

z=\frac{\sqrt{3}+i}{\sqrt{3}-i}=\frac{(\sqrt{3}+i)(\sqrt{3}+i)}{(\sqrt{3}-i)(\sqrt{3}+i)}=\frac{2+2 i \sqrt{3}}{4}=\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} i \sqrt{3}

\)

Clearly, the point representing \(z\) lies in the first quadrant.

\(

\therefore \quad \text { principal argument } \arg (z)=\tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{\operatorname{Im}(z)}{\operatorname{Re}(z)}\right)=\tan ^{-1} \sqrt{3}=\frac{\pi}{3}

\)

Example 2: Let \(z\) be a purely imaginary number such that \(\operatorname{Im}(z)>0\). Then, \(\arg (z)\) is equal to

(a) \(\pi\)

(b) \(\pi / 2\)

(c) 0

(d) \(-\pi / 2\)

Solution: (b) Let \(z=0+b i\), where \(b>0\). Then, \(z\) lies on \(y\)-axis.

So, \(\arg (z)=\frac{\pi}{2}\).

Example 3: Let \(z\) be a purely imaginary number such that \(\operatorname{Im}(\mathrm{z})<0\). Then, \(\arg (\mathrm{z})\) is equal to

(a) \(\pi\)

(b) \(\pi / 2\)

(c) 0

(d) \(-\pi / 2\)

Solution: (d) Let \(z=0+i b\), where \(b<0\). Then, \(z\) is represented by a point on the negative direction of \(y\)-axis.

\(

\therefore \quad \arg (z)=-\pi / 2 .

\)

Example 4: If \(z\) is a purely real number such that \(\operatorname{Re}(z)<0\), then \(\arg (z)\) is equal to

(a) \(\pi\)

(b) \(\pi / 2\)

(c) 0

(d) \(-\pi / 2\)

Solution: (a) Let \(z=a+i 0\), where \(a<0\). Then, \(z\) is represented by a point on negative side of \(x\)-axis.

\(

\therefore \quad \arg (z)=\pi .

\)

Example 5: Let \(z\) be any non-zero complex number. Then, \(\arg (z)+\arg (z)\) is equal to

(a) \(\pi\)

(b) \(-\pi\)

(c) 0

(d) \(\pi / 2\)

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \arg (z)+\arg (z)=\arg (z)+2 n \pi-\arg (z), n \in Z \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \arg (z)+\arg (z)=2 n \pi, n \in Z

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 6: If \(z=x+i y\) is a variable complex number such that \(\arg \left(\frac{z-1}{z+1}\right)=\frac{\pi}{4}\), then [JEE (WB) 2006]

(a) \(x^2-y^2-2 x-1=0\)

(b) \(x^2+y^2-2 x-1=0\)

(c) \(x^2+y^2-2 y-1=0\)

(d) \(x^2+y^2+2 x-1=0\)

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{z-1}{z+1}=\frac{(x-1)+i y}{(x+1)+i y}=\frac{\left(x^2+y^2-1\right)+2 i y}{(x+1)^2+y^2} \\

\therefore & \arg \left(\frac{z-1}{z+1}\right)=\frac{\pi}{4} \\

\Rightarrow & \tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{2 y}{x^2+y^2-1}\right)=\frac{\pi}{4} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{2 y}{x^2+y^2-1}=\tan \frac{\pi}{4} \Rightarrow x^2+y^2-2 y-1=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 7: Find the amplitude (argument) of

a. \(\frac{1+\sqrt{3} i}{\sqrt{3}+i}\)

b. \(-1-i \sqrt{3}\)

c. \(\sin \alpha+i(1-\cos \alpha), 0<\alpha<\pi\)

Solution: (a) \(\operatorname{amp}\left(\frac{1+\sqrt{3} i}{\sqrt{3}+i}\right)=\operatorname{amp}(1+\sqrt{3} i)-\operatorname{amp}(\sqrt{3}+i)\)

\(

=\frac{\pi}{3}-\frac{\pi}{6}=\frac{\pi}{6}

\)

(b) Let, \(z=-1-i \sqrt{3}\).

Then \(\alpha=\tan ^{-1}|b / a|=\tan ^{-1}|\sqrt{3} / 1|=\pi / 3\)

Here, \(z\) is in third quadrant. Therefore argument is \(\theta=-(\pi-\alpha)=-(\pi-\pi / 3)=-2 \pi / 3\)

(c)

\(

\begin{aligned}

z=\sin \alpha & +i(1-\cos \alpha), 0<\alpha<\pi=\sin \alpha+i(1-\cos \alpha) \\

\operatorname{amp}(z) & =\tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{1-\cos \alpha}{\sin \alpha}\right)(\because z \text { lies in first quadrant }) \\

& =\tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{2 \sin ^2 \frac{\alpha}{2}}{2 \sin \frac{\alpha}{2} \cos \frac{\alpha}{2}}\right)=\tan ^{-1} \tan \left(\frac{\alpha}{2}\right)=\frac{\alpha}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 8: Find the modulus, argument and the principal argument of the complex numbers.

(i) \((\tan 1-i)^2\)

(ii) \(\frac{i-1}{i\left(1-\cos \frac{2 \pi}{5}\right)+\sin \frac{2 \pi}{5}}\)

Solution: (i)

\(

\begin{aligned}

z & =(\tan 1-i)^2=\left(\tan ^2 1-1\right)-(2 \tan 1) i \\

|z| & =\sqrt{\left(\tan ^2 1-1\right)^2+4 \tan ^2 1} \\

& =\sqrt{\left(\tan ^2 1+1\right)^2}=\tan ^2 1+1

\end{aligned}

\)

Since \(\tan ^2 1-1<0\) and \(-2 \tan 1<0\)

\(\Rightarrow z\) lies on third quadrant

\(

\begin{aligned}

\Rightarrow \arg (z) & =-\pi+\tan ^{-1}\left|\frac{2 \tan 1}{1-\tan ^2 1}\right| \\

& =-\pi+\tan ^{-1}|\tan 2| \\

& =2-\pi

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii)

\(\begin{aligned} z & =\frac{i-1}{i\left(1-\cos \frac{2 \pi}{5}\right)+\sin \frac{2 \pi}{5}} \\ & =\frac{i-1}{i 2 \sin ^2 \frac{\pi}{5}+2 \sin \frac{\pi}{5} \cos \frac{\pi}{5}} \\ & =\frac{i-1}{\left(2 \sin \frac{\pi}{5}\right)\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{5}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{5}\right)} \\ |z| & =\frac{|i-1|}{\left(2 \sin \frac{\pi}{5}\right)\left|\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{5}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{5}\right)\right|}\end{aligned}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =\frac{\sqrt{2}}{\left(2 \sin \frac{\pi}{5}\right)\left|\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{5}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{5}\right)\right|} \\

& =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \operatorname{cosec} \frac{\pi}{5} \\

\arg z & =\arg \left[\frac{i-1}{\left(2 \sin \frac{\pi}{5}\right)\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{5}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{5}\right)}\right] \\

& =\arg (-1+i)-\arg \left(2 \sin \frac{\pi}{5}\right)-\arg \left(\cos \frac{\pi}{5}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{5}\right) \\

& =\frac{3 \pi}{4}-0-\frac{\pi}{5}=\frac{11 \pi}{20}

\end{aligned}

\)

Properties of Arguments

- \(\arg \left(z_1 z_2\right)=\arg \left(z_1\right)+\arg \left(z_2\right)\).

In general,

\(

\begin{aligned}

\arg \left(z_1 z_2 z_3 \cdots z_n\right)=\arg \left(z_1\right)+\arg \left(z_2\right)+\arg \left(z_3\right) & +\cdots \\

& +\arg \left(z_n\right)

\end{aligned}

\) - \(\arg \left(\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right)=\arg z_1-\arg z_2\)

- \(\arg \bar{z}=-\arg z\)

- \(\arg \left(\frac{1}{\bar{z}}\right)=-\arg z\),

- \(\arg \left(\frac{z}{\bar{z}}\right)=\arg (z)-\arg (\bar{z})=\theta-(-\theta) = 2 \theta=2 \arg (z), \text { where } \theta=\arg (z) \text {. }\)

- \(\arg \left(z^n\right)=n \arg z\), when \(n \in \theta\).

- \(z_1 \bar{z}_2+\bar{z}_1 z_2=2\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| \cos \left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)\), where \(\theta_1=\arg \left(z_1\right)\) and \(\theta_2=\arg \left(z_2\right)\).

- If \(z\) is purely imaginary, then \(\arg (z)= \pm \pi / 2\).

- If \(z\) is purely real, then \(\arg (z)=0\) or \(\pi\).

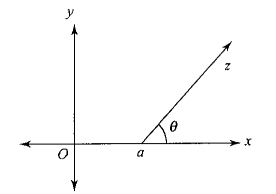

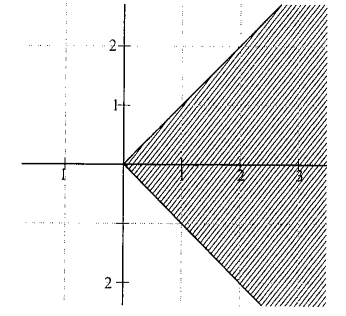

- Locus of \(z\), if \(\arg (z)=\theta\) ( \(=\) constant) is ray excluding origin (ray originating from the origin but excluding the origin itself). For the argument to be defined, \(z\) cannot be the origin \((0,0)\), as the origin does not have a well-defined angle.

- Locus of \(z\), if \(\arg (z-a)=\theta(=\) constant \()\) and \(a>0\)

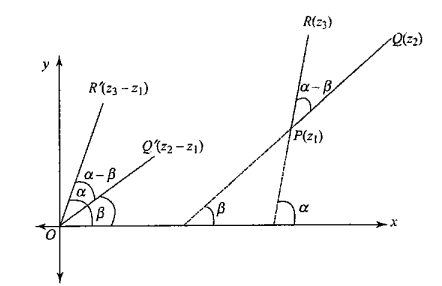

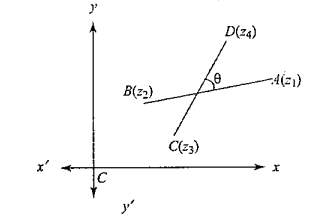

- Angle between two lines,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =\alpha-\beta \\

& =\arg \left(z_3-z_1\right)-\arg \left(z_2-z_1\right) \\

& =\arg \left(\frac{z_3-z_1}{z_2-z_1}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

- Angle between lines joining \(z_1, z_2\) and \(z_3, z_4\) :

\(

\theta=\arg \left(\frac{z_4-z_3}{z_1-z_2}\right)

\)

Note: By specifying the modulus and argument, a complex number is completely defined. However, for the complex number \(0+0i\) the argument is not defined and this is the only complex number which is completely defined by taking in terms of its modulus.

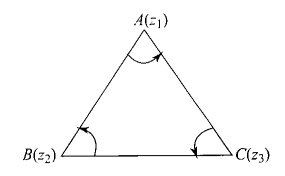

Example 9: If \(z_1, z_2, z_3\) be the vertices of an equilateral triangle, then

\(

\frac{1}{z_1-z_2}+\frac{1}{z_2-z_3}+\frac{1}{z_3-z_1}=0

\)

or \(z_1^2+z_2^2+z_3^2=z_1 z_2+z_2 z_3+z_3 z_1\)

Solution:

Since \(\triangle A B C\) is equilateral, therefore

\(

\begin{aligned}

& A B=B C=C A \\

\therefore & \left|z_1-z_2\right|=\left|z_2-z_3\right|=\left|z_3-z_1\right| \\

\therefore & \left|\frac{z_1-z_2}{z_3-z_2}\right|=\left|\frac{z_2-z_3}{z_1-z_3}\right| \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

Also,

\(

\angle C B A=\angle A C B

\)

\(

\therefore \quad \arg \left(\frac{z_1-z_2}{z_3-z_2}\right)=\arg \left(\frac{z_2-z_3}{z_1-z_3}\right) \dots(ii)

\)

From (i) and (ii), it follows that

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{z_1-z_2}{z_3-z_2}=\frac{z_2-z_3}{z_1-z_3} \\

\Rightarrow & \left(z_1-z_2\right)\left(z_1-z_3\right)=-\left(z_2-z_3\right)^2 \\

\Rightarrow & z_1^2-z_1 z_2-z_1 z_3+z_2 z_3=-\left(z_2^2+z_3^2-2 z_2 z_3\right) \\

\Rightarrow & z_1^2+z_2^2+z_3^2=z_1 z_2+z_2 z_3+z_3 z_1

\end{aligned}

\)

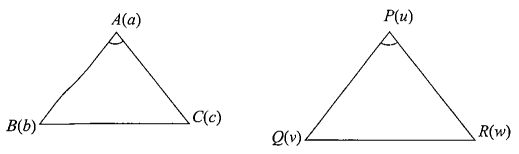

Example 10: If \(a, b, c\) and \(u, v, w\) are complex numbers representing the vertices of two triangles such that they are similar, then \(\left|\begin{array}{lll}a & u & 1 \\ b & v & 1 \\ c & w & 1\end{array}\right|=0\) or \(\frac{a-c}{a-b}=\frac{u-w}{u-v}\)

Solution:

In the figure triangles are similar. Hence

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{A C}{P R}=\frac{A B}{P Q} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{A C}{A B}=\frac{P R}{P Q} \\

\Rightarrow & \left|\frac{a-c}{a-b}\right|=\left|\frac{u-w}{u-v}\right| \dots(1)

\end{aligned}

\)

Also,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \angle B A C=\angle Q P R \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \arg \left(\frac{a-c}{a-b}\right)=\arg \left(\frac{u-w}{u-v}\right) \dots(2)

\end{aligned}

\)

From (1) and (2), we have

\(

\frac{a-c}{a-b}=\frac{u-w}{u-v}

\)

Simplifying, we get

\(

\left|\begin{array}{lll}

a & u & 1 \\

b & v & 1 \\

c & w & 1

\end{array}\right|=0

\)

Example 11: If \(z_1, z_2\) and \(z_3, z_4\) are two pairs of conjugate complex numbers, then find the value of \(\boldsymbol{\operatorname { a r g }}\left(z_1 / z_4\right)+\boldsymbol{\operatorname { a r g }}\left(z_2 / z_3\right)\).

Solution: We have \(z_2=\bar{z}_1\) and \(z_4=\bar{z}_3\). Therefore,

\(

z_1 z_2=\left|z_1\right|^2 \text { and } z_3 z_4=\left|z_3\right|^2

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \arg \left(\frac{z_1}{z_4}\right)+\arg \left(\frac{z_2}{z_3}\right)=\arg \left(\frac{z_1 z_2}{z_4 z_3}\right) \\

& =\arg \left(\frac{\left|z_1\right|^2}{\left|z_3\right|^2}\right) \\

& =\arg \left(\left|\frac{z_1}{z_3}\right|^2\right)=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Since \(\left|\frac{z_1}{z_3}\right|^2\) is a positive real number (because it is a ratio of squared moduli.), its argument is \(\mathbf{0}\).

Example 12: Prove that \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|=\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right| \Rightarrow \arg \left(z_1\right) =\boldsymbol{\operatorname { a r g }}\left(z_2\right)\).

Solution: Start by squaring both sides:

\(

\left|z_1+z_2\right|^2=\left(\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right|\right)^2 .

\)

Compute each side separately.

Left-hand side:

\(

\left|z_1+z_2\right|^2=\left(z_1+z_2\right)\left(\overline{z_1}+\overline{z_2}\right)=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2+2 \Re\left(z_1 \overline{z_2}\right) .

\)

Right-hand side:

\(

\left(\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right|\right)^2=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2+2\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| .

\)

Equating these:

\(

\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2+2 \Re\left(z_1 \overline{z_2}\right)=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2+2\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| .

\)

Cancel common terms:

\(

\Re\left(z_1 \overline{z_2}\right)=\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| .

\)

Use polar form

Write

\(

z_1=\left|z_1\right| e^{i \theta_1}, \quad z_2=\left|z_2\right| e^{i \theta_2} .

\)

Then

\(

z_1 \overline{z_2}=\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| e^{i\left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)} .

\)

So

\(

\Re\left(z_1 \overline{z_2}\right)=\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| \cos \left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right) .

\)

Substitute into the earlier equality:

\(

\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| \cos \left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)=\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right|

\)

Since \(\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right|>0\) unless one number is 0 (the result is still true in that trivial case), divide both sides:

\(

\cos \left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)=1

\)

Thus

\(

\theta_1-\theta_2=0+2 \pi k, \quad k \in \mathbb{Z}

\)

Hence:

\(

\arg \left(z_1\right)=\arg \left(z_2\right)

\)

Explanation:

The condition \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|=\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right|\) is the equality case of the triangle inequality. Equality holds only when the two complex numbers point in exactly the same direction, i.e., their arguments are equal.

Example 13: If \(\arg \left(z_1\right)=170^{\circ}\) and \(\arg \left(z_2\right)=70^{\circ}\), then find the principal argument of \(z_1 z_2\).

Solution: Step 1: Use the argument addition rule

\(

\arg \left(z_1 z_2\right)=\arg \left(z_1\right)+\arg \left(z_2\right)=170^{\circ}+70^{\circ}=240^{\circ} .

\)

So the argument of the product is \(240^{\circ}\).

Step 2: Convert to principal argument

The principal argument must lie in:

\(

\left(-180^{\circ}, 180^{\circ}\right] .

\)

Since

\(

240^{\circ}>180^{\circ},

\)

subtract \(360^{\circ}\) :

\(

240^{\circ}-360^{\circ}=-120^{\circ} .

\)

This makes sense because \(240^{\circ}\) is in the 3 rd quadrant, and the corresponding principal argument is \(-120^{\circ}\).

Example 14: If \(z_1\) and \(z_2\) are conjugate to each other, then find \(\boldsymbol{\operatorname { a r g }}\left(-z_1 z_2\right)\).

Solution: \(z_1\) and \(z_2\) are conjugate to each other, i.e., \(z_2=\bar{z}_1\). Therefore,

\(

\arg \left(-z_1 z_2\right)=\arg \left(-z_1 \overline{z_1}\right)=\arg \left(-\left|z_1\right|^2\right) .

\)

Since \(\left|z_1\right|^2>0\), the expression \(-\left|z_1\right|^2\) is a negative real number.

The argument of any negative real number is:

\(\pi\).

Thus:

\(

\arg \left(-z_1 z_2\right)=\pi .

[latex]

\)

This is the principal argument, and it follows from the fact that negative real numbers lie on the negative \(x\) axis.

Example 15: If \(\pi / 2<\alpha<3 \pi / 2\), then find the modulus and argument of \((1+\cos 2 \alpha)+i \sin 2 \alpha\).

Solution: Given

\(

z=(1+\cos 2 \alpha)+i \sin 2 \alpha, \quad \frac{\pi}{2}<\alpha<\frac{3 \pi}{2} .

\)

Step 1: Apply trigonometric identities

Use the double-angle identities:

\(

1+\cos 2 \alpha=2 \cos ^2 \alpha, \quad \sin 2 \alpha=2 \sin \alpha \cos \alpha

\)

Thus,

\(

z=2 \cos ^2 \alpha+i 2 \sin \alpha \cos \alpha=2 \cos \alpha(\cos \alpha+i \sin \alpha) .

\)

Step 2: Handle the sign of \(\cos \alpha\)

Since

\(

\frac{\pi}{2}<\alpha<\frac{3 \pi}{2},

\)

\(\alpha\) is in the left half-plane (2nd or 3rd quadrant), so:

\(

\cos \alpha<0 .

\)

We want the modulus to be positive, so extract the negative sign:

\(

2 \cos \alpha(\cos \alpha+i \sin \alpha)=-2 \cos \alpha[-\cos \alpha-i \sin \alpha] .

\)

Now observe:

\(

-\cos \alpha-i \sin \alpha=\cos (\alpha-\pi)+i \sin (\alpha-\pi) .

\)

So:

\(

z=-2 \cos \alpha[\cos (\alpha-\pi)+i \sin (\alpha-\pi)]

\)

Step 3: Read modulus and argument

Thus:

\(

|z|=-2 \cos \alpha \quad(\text { positive, since } \cos \alpha<0)

\)

and

\(

\arg (z)=\alpha-\pi

\)

\(

|z|=-2 \cos \alpha, \quad \arg (z)=\alpha-\pi .

\)

Both results follow directly from the trigonometric identities and the sign of \(\cos \alpha\) on ( \(\pi / 2,3 \pi / 2\) ).

Example 16: Let \(z\) and \(w\) be two non-zero complex numbers such that \(|z|=|w|\) and \(\arg (z)+\arg (w)=\pi\). Then prove that \(z=-\bar{w}\).

Solution: Let \(\arg (w)=\theta\). Then \(\arg (z)=\pi-\theta\). Therefore,

\(

w=|w|(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)

\)

and

\(

\begin{aligned}

& z=|z|(\cos (\pi-\theta)+i \sin (\pi-\theta)) \\

& =|w|(-\cos \theta+i \sin \theta) \quad[\because|z|=|w|] \\

& =-|w|(\cos \theta-i \sin \theta)=-\bar{w}

\end{aligned}

\)

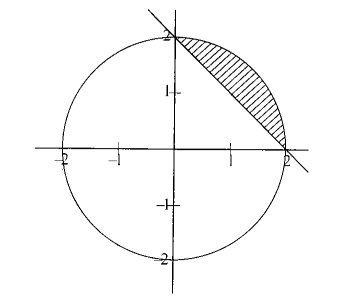

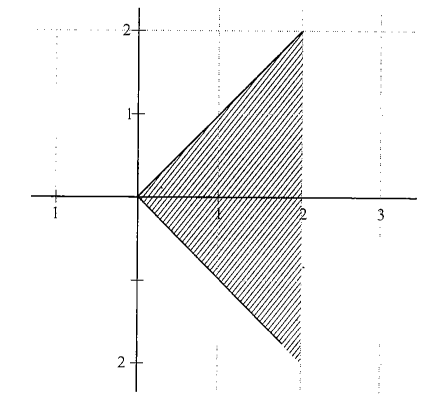

Example 17: Let \(z=x+i y\) be a complex number, where \(x\) and \(y\) are real numbers. Let \(A\) and \(B\) be the sets defined by \(A=\{z:|z| \leq 2\}\) and \(B=\{z:(1-i) z+(1+i) \bar{z} \geq 4 \mid\}\). Find the area of region \(\boldsymbol{A} \cap \boldsymbol{B}\).

Solution:

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& z=x+i y \\

& A=\{z:|z| \leq 2\} \\

\Rightarrow & \sqrt{x^2+y^2} \leq 2 \\

\Rightarrow & x^2+y^2 \leq 4 \\

\Rightarrow & z \text { lies on or inside the circle } x^2+y^2=4 \\

& B=\{z:(1-\mathrm{i}) z+(1+\mathrm{i}) \bar{z} \geq 4\} \\

\Rightarrow & (1-\mathrm{i})(x+i y)+(1+i)(x-i y) \geq 4 \\

\Rightarrow & x+i y-\mathrm{i} x+y+x-i y+i x+y \geq 4 \\

\Rightarrow & x+y \geq 2

\end{array}

\)

Area of region \(A \cap B\) is shaded region the diagram.

\(

\text { Area }=\frac{\pi(2)^2}{4}-\frac{1}{2} \times 2 \times 2=\pi-2

\)

Example 18: Find the area bounded by \(\arg |z| \leq \pi / 4\) and \(|z-1|<|z-3|\).

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \operatorname{larg} z 1<\pi / 4 \\

& -\pi / 4<\arg z<\pi / 4 \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

Which represents the region given in the following diagram.

\begin{aligned}

& |z-1|<|z-3| \\

\Rightarrow & (x-1)^2+y^2<(x-3)^2+y^2 \\

\Rightarrow & x<2 \dots(ii)

\end{aligned}

\)

Common region of (i) and (ii) is shown in above figure. Area of the shaded region is \(\frac{1}{2}(4)(2)=4\) square units.

Example 19: If \(z+1 / z=2 \cos \theta\), prove that

\(

\left|\left(z^{2 n}-1\right) /\left(z^{2 n}+1\right)\right|=|\tan n \theta|

\)

Solution: \(z+\frac{1}{z}=2 \cos \theta\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow z^2-2 \cos \theta z+1=0 \\

& \Rightarrow z=\frac{2 \cos \theta \pm \sqrt{4 \cos ^2 \theta-4}}{2} \\

& =\cos \theta+i \sin \theta

\end{aligned}

\)

Taking positive sign,

\(

z=\cos \theta+i \sin \theta, \frac{1}{z}=(\cos \theta-i \sin \theta)

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{aligned}

\therefore \quad & \frac{z^{2 n}-1}{z^{2 n}+1}=\frac{z^n-\frac{1}{z^n}}{z^n+\frac{1}{z^n}} \\

& =\frac{(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^n-(\cos \theta-i \sin \theta)^n}{(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^n+(\cos \theta-i \sin \theta)^n} \\

& =\frac{2 i \sin n \theta}{2 \cos n \theta} \\

& =i \tan n \theta

\end{aligned}\\

&\text { Taking negative sign, we get }\\

&\begin{aligned}

& \frac{z^{2 n}-1}{z^{2 n}+1}=\frac{-2 i \sin n \theta}{2 \cos n \theta}=-\tan n \theta \\

\Rightarrow & \left|\frac{z^{2 n}-1}{z^{2 n}+1}\right|=| \pm i \tan \theta|=\tan n \theta

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

DE MOIVRE’S THEOREM

Statement:

(i) If \(n \in Z\) (the set of integers), then

\(

(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^n=\cos n \theta+i \sin n \theta

\)

(ii) If \(n \in Q\) (the set of rational numbers), then \(\cos n \theta+i \sin n \theta\) is one of the values of \((\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^n\).

Proof:

(i) When \(n \in Z\), we know that

\(

\begin{aligned}

& e^{i \theta}=\cos \theta+i \sin \theta \\

\Rightarrow & \left(e^{i \theta}\right)^n=(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^n \\

\Rightarrow & e^{i n \theta \theta}=(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^n \\

\Rightarrow & \cos (n \theta)+i \sin (n \theta)=(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^n

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) Let \(n\) be rational number. Let \(n=p / q\), where \(p, q\) are integers and \(q \neq 0\). From part (i), we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

\left(\cos \frac{p \theta}{q}+i \sin \frac{p \theta}{q}\right)^q & =\cos \left(\left(\frac{p \theta}{q}\right) q\right)+i \sin \left(\left(\frac{p \theta}{q}\right) q\right) \\

& =\cos p \theta+i \sin p \theta

\end{aligned}

\)

\(\Rightarrow \cos \frac{p \theta}{q}+i \sin \frac{p \theta}{q}\) is one of the values of

\((\cos p \theta+i \sin p \theta)^{1 / q}\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad \cos \frac{p \theta}{q}+i \sin \frac{p \theta}{q}\) is one of the values of

\(\left[(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^{p}\right]^{1 / q}\)

\(\Rightarrow \cos \frac{p \theta}{q}+i \sin \frac{p \theta}{q}\) is one of the values of

\((\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^{p / q}\)

- Remark 1: This theorem is also true for \((\cos \theta-i \sin \theta)^n\) i.e. \((\cos \theta-i \sin \theta)^n=\cos n \theta-i \sin n \theta\)

- Remark 2: \(\frac{1}{\cos \theta+i \sin \theta}=(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^{-1}=\cos \theta-i \sin \theta\)

- Remark 3: \((\sin \theta+i \cos \theta)^n \neq \sin n \theta+i \cos n \theta\)

In fact

\(

\begin{aligned}

\quad(\sin \theta+i \cos \theta)^n & =\left\{\cos \left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right)+i \sin \left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right)\right\}^n \\

\Rightarrow \quad(\sin \theta+i \cos \theta)^n & =\cos n\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right)+i \sin n\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right)

\end{aligned}

\) - Remark 4: \((\cos \theta+i \sin \phi)^n \neq \cos n \theta+i \sin n \phi\)

- Remark 5: Writing the binomial expression of \((\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)^n\) and equating the real part to \(\cos n \theta\) and the imaginary part to \(\sin n \theta\), we get

\(

\begin{gathered}

\cos (n \theta)=\cos ^n \theta-{ }^n C_2 \cos ^{n-2} \theta \sin ^2 \theta+{ }^n C_4 \cos ^{n-4} \theta \sin ^4 \theta+\cdots \\

\sin (n \theta)={ }^n C_1 \cos ^{n-1} \theta \sin \theta-{ }^n C_3 \cos ^{n-3} \theta \sin ^3 \theta \\

+{ }^n C_5 \cos ^{n-5} \theta \sin ^5 \theta-\cdots \\

\tan (n \theta)=\frac{{ }^n C_1 \tan \theta-{ }^n C_3 \tan ^3 \theta+{ }^n C_5 \tan ^5 \theta-{ }^n C_7 \tan ^7 \theta+\cdots}{1-{ }^n C_2 \tan ^2 \theta+{ }^n C_4 \tan ^4 \theta-{ }^n C_6 \tan ^6 \theta+\cdots}

\end{gathered}

\)

Example 20: \(\left\{\frac{1+\cos \pi / 8+i \sin \pi / 8}{1+\cos \pi / 8-i \sin \pi / 8}\right\}^8=\)

(a) \(1+i\)

(b) \(1-i\)

(c) 1

(d) -1

Solution: (d) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{1+\cos \pi / 8+i \sin \pi / 8}{1+\cos \pi / 8-i \sin \pi / 8} \\

& =\frac{2 \cos ^2 \pi / 16+2 i \sin \pi / 16 \cos \pi / 16}{2 \cos ^2 \pi / 16-2 i \sin \pi / 16 \cos \pi / 16} \\

& =\frac{\cos \pi / 16+i \sin \pi / 16}{\cos \pi / 16-i \sin \pi / 16} \\

\therefore \quad & \left\{\frac{1+\cos \pi / 8+i \sin \pi / 8}{1+\cos \pi / 8-i \sin \pi / 8}\right\}^8 \\

& =\frac{\cos 8 \pi / 16+i \sin 8 \pi / 16}{\cos 8 \pi / 16-i \sin 8 \pi / 16}=\frac{\cos \pi / 2+i \sin \pi / 2}{\cos \pi / 2-i \sin \pi / 2}=-1

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 21: \(\frac{(\sin \pi / 8+i \cos \pi / 8)^8}{(\sin \pi / 8-i \cos \pi / 8)^8}=\)

(a) -1

(b) 0

(c) 1

(d) \(2 i\)

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\frac{(\sin \pi / 8+i \cos \pi / 8)^8}{(\sin \pi / 8-i \cos \pi / 8)^8}

\)

\(

=\frac{i^8(\cos \pi / 8-i \sin \pi / 8)^8}{(-i)^8(\cos \pi / 8+i \sin \pi / 8)^8}=\frac{\cos \pi-i \sin \pi}{\cos \pi+i \sin \pi}=1 .

\)

Example 22: The principal amplitude of \(\left(\sin 40^{\circ}+i \cos 40^{\circ}\right)^5\) is [JEE ( WB) 2008]

(a) \(70^{\circ}\)

(b) \(-110^{\circ}\)

(c) \(110^{\circ}\)

(d) \(-70^{\circ}\)

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(\sin 40^{\circ}+\cos 40^{\circ}\right)^5=\left(\cos 50^{\circ}+\sin 50^{\circ}\right)^5 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \left(\sin 40^{\circ}+\cos 40^{\circ}\right)^5=\cos 250^{\circ}+\sin 250^{\circ} \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \left(\sin 40^{\circ}+\cos 40^{\circ}\right)^5=\cos \left(360^{\circ}-250^{\circ}\right)+i \sin \left(360^{\circ}-250^{\circ}\right) \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \left(\sin 40^{\circ}+\cos 40^{\circ}\right)^5=\cos 110^{\circ}-i \sin 110^{\circ} \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \left(\sin 40^{\circ}+\cos 40^{\circ}\right)^5=\cos \left(-110^{\circ}\right)+i \sin \left(-110^{\circ}\right) \\

\therefore \quad & \text { Principal amplitude of }\left(\sin 40^{\circ}+\cos 40^{\circ}\right)^5 \text { is }-110^{\circ} .

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 23: If \(\cos \alpha+\cos \beta+\cos \gamma=\sin \alpha+\sin \beta+\sin \gamma=0\), then the value of \(\cos 3 \alpha+\cos 3 \beta+\cos 3 \gamma\) is

(a) 0

(b) \(\cos (\alpha+\beta+\gamma)\)

(c) \(3 \cos (\alpha+\beta+\gamma)\)

(d) \(3 \sin (\alpha+\beta+\gamma)\)

Solution: (c) Let \(a=\cos \alpha+i \sin \alpha\), \(b=\cos \beta+i \sin \beta\), and,

\(

c=\cos \gamma+i \sin \gamma

\)

Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a+b+c=(\cos \alpha+\cos \beta+\cos \gamma)+i(\sin \alpha+\sin \beta+\sin \gamma) \\

\Rightarrow & a+b+c=0+i 0=0 \\

\Rightarrow & a^3+b^3+c^3=3 a b c \\

\Rightarrow & (\cos 3 \alpha+i \sin 3 \alpha)+(\cos 3 \beta+i \sin 3 \beta)+(\cos 3 \gamma+i \sin 3 \gamma) \\

& =3[\cos (\alpha+\beta+\gamma)+i \sin (\alpha+\beta+\gamma)] \\

\Rightarrow & \cos 3 \alpha+\cos 3 \beta+\cos 3 \gamma=3 \cos (\alpha+\beta+\gamma) .

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 24: If \(x_n=\cos \frac{\pi}{2^n}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{2^n}, n \in N\), then \(x_1, x_2, x_3 \ldots x_{\infty}\) is equal to [CEE (Delhi) 2003]

(a) 1

(b) -1

(c) 0

(d) none of these

Solution: The terms of the product are given by \(x_n=\cos \left(\frac{\pi}{2^n}\right)+i \sin \left(\frac{\pi}{2^n}\right)\). This can be expressed in Euler’s form as \(x_n=e^{i \frac{\pi}{2^n}}\).

The infinite product is:

\(

P=x_1 x_2 x_3 \ldots x_{\infty}=\prod_{n=1}^{\infty} x_n

\)

Substituting the Euler’s form:

\(

\boldsymbol{P}=e^{i \frac{\pi}{2^1}} \cdot e^{i \frac{\pi}{2^2}} \cdot e^{i \frac{\pi}{2^3}} \cdots=e^{i\left(\frac{\pi}{2}+\frac{\pi}{2^2}+\frac{\pi}{2^3}+\cdots\right)}

\)

The exponent is a sum of an infinite geometric series with:

First term, \(a=\frac{\pi}{2}\)

Common ratio, \(r=\frac{1}{2}\)

The sum of an infinite geometric series is given by the formula \(S=\frac{a}{1-r}\), provided \(|r|<1\). Here, \(|r|=\frac{1}{2}<1\), so the series converges.

The sum of the angles is:

\(

S=\frac{\frac{\pi}{2}}{1-\frac{1}{2}}=\frac{\frac{\pi}{2}}{\frac{1}{2}}=\pi

\)

Substituting this sum back into the expression for \(P\).

\(

\boldsymbol{P}=e^{i \pi}

\)

Using Euler’s formula, \(e^{i \theta}=\cos (\theta)+i \sin (\theta)\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

P=\cos (\pi)+i \sin (\pi) \\

P=-1+i \cdot 0 \\

P=-1

\end{gathered}

\)

Thus, the infinite product is equal to -1.

Example 25: If \((\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)(\cos 2 \theta+i \sin 2 \theta) \ldots\). \(\ldots .(\cos n \theta+i \sin n \theta)=1\), then the value of \(\theta\), is

(a) \(4 m \pi\)

(b) \(\frac{2 m \pi}{n(n+1)}\)

(c) \(\frac{4 m \pi}{n(n+1)}\)

(d) \(\frac{m \pi}{n(n+1)}\)

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)(\cos 2 \theta+i \sin 2 \theta) \ldots(\cos n \theta+i \sin n \theta)=1 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \cos (\theta+2 \theta+3 \theta+\ldots+n \theta)+i \sin (\theta+2 \theta+\ldots+n \theta)=1 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \cos \left\{\frac{n(n+1)}{2} \theta\right\}+i \sin \left\{\frac{n(n+1)}{2} \theta\right\}=1 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \cos \left\{\frac{n(n+1)}{2} \theta\right\}=1 \text { and, } \sin \left\{\frac{n(n+1)}{2} \theta\right\}=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{n(n+1)}{2} \theta=2 m \pi \Rightarrow \theta=\frac{4 m \pi}{n(n+1)}, \text { where } m \in Z .

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 26: If \(x+\frac{1}{x}=2 \cos \theta\), then \(x^n+\frac{1}{x^n}\) is equal to

(a) \(2 \cos n \theta\)

(b) \(2 \sin n \theta\)

(c) \(\cos n \theta\)

(d) \(\sin n \theta\)

Solution: (a) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x+\frac{1}{x}=2 \cos \theta \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-2 x \cos \theta+1=0 \\

\Rightarrow & x=\cos \theta \pm i \sin \theta \\

\Rightarrow & x^n=\cos n \theta \pm i \sin n \theta \Rightarrow \frac{1}{x^n}=\cos n \theta \mp i \sin n \theta \\

\therefore & x^n+\frac{1}{x^n}=2 \cos n \theta .

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 27: Find the value of the expression

\(

\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{2}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{2}\right)\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{2^2}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{2^2}\right) \ldots \text { to } \infty

\)

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(\cos \frac{\pi}{2}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{2}\right)\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{2^2}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{2^2}\right) \ldots \text { to } \infty \\

& =\cos \left(\frac{\pi}{2}+\frac{\pi}{2^2}+\cdots\right)+i \sin \left(\frac{\pi}{2}+\frac{\pi}{2^2}+\cdots\right) \\

& =\cos \left[\frac{\pi}{2}\left(1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2^2}+\cdots\right)\right]+i \sin \left[\frac{\pi}{2}\left(1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2^2}+\cdots\right)\right] \\

& =\cos \left[\frac{\pi}{2}\left(\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{2}}\right)\right]+i \sin \left[\frac{\pi}{2}\left(\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{2}}\right)\right]=\cos \pi+i \sin \pi=-1

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 28: If \(z=(\sqrt{3}+i)^{17} /(1-i)^{50}\), then find amp \((z)\).

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

z=\frac{(\sqrt{3}+i)^{17}}{(1-i)^{50}} & =\frac{\left[2\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}+\frac{i}{2}\right)\right]^{17}}{\left[\sqrt{2}\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}-\frac{i}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\right]^{50}} \\

& =\frac{2^{17}\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{6}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{6}\right)^{17}}{2^{25}\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{4}-i \sin \frac{\pi}{4}\right)^{50}}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =\frac{\left(\cos \frac{17 \pi}{6}+i \sin \frac{17 \pi}{6}\right)}{2^8\left(\cos \frac{50 \pi}{4}-i \sin \frac{50 \pi}{4}\right)} \\

& =\frac{\left[\cos \left(2 \pi+\frac{5 \pi}{6}\right)+i \sin \left(2 \pi+\frac{5 \pi}{6}\right)\right]}{2^8\left[\cos \left(12 \pi+\frac{\pi}{2}\right)-i \sin \left(12 \pi+\frac{\pi}{2}\right)\right]}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =\frac{\left(\cos \frac{5 \pi}{6}+i \sin \frac{5 \pi}{6}\right)}{2^8\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{2}-i \sin \frac{\pi}{2}\right)} \\

& =\frac{\left(\cos \frac{5 \pi}{6}+i \sin \frac{5 \pi}{6}\right)}{2^8\left[\cos \left(-\frac{\pi}{2}\right)+i \sin \left(-\frac{\pi}{2}\right)\right]}

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence,

\(

\arg (z)=\frac{5 \pi}{6}-\left(-\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=\frac{4 \pi}{3}

\)

Thus \(z\) lies in the third quadrant and principal argument is \(-2 \pi / 3\).

Roots Of a Complex Number

Let \(\mathrm{z}=a+i b\) be a complex number, and let \(r(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)\) be the polar form of \(z\). Then, by De-Moivere’s theorem \(r^{1 / n}\left\{\cos \left(\frac{\theta}{n}\right)+i \sin \left(\frac{\theta}{n}\right)\right)\) is one of the values of \(z^{1 / n}\).

Here, we shall show that \(z^{1 / n}\) has \(n\) distinct values.

We know that

\(

\cos \theta+i \sin \theta=\cos (2 m \pi+\theta)+i \sin (2 m \pi+\theta), m=0,1,2, \ldots

\)

So, \(z^{1 / n}=r^{1 / n}\left[\cos (2 m \pi+\theta)+i \sin (2 m \pi+\theta]^{1 / n}\right.\)

\(

\Rightarrow z^{1 / n}=r^{1 / n}\left[\cos \frac{2 m \pi+\theta}{n}+i \sin \frac{2 m \pi+\theta}{n}\right]

\)

Now by giving \(m\) the values \(0,1,2, \ldots,(n-1)\); we shall obtain distinct values of \(z^{1 / n}\).

For the values \(m=n, n+1, \ldots\), the values of \(z^{1 / n}\) will repeat.

For example, if \(m=n\), then

\(

\begin{array}{rlrl}

& z^{1 / n} =r^{1 / n}\left\{\cos \frac{2 n \pi+\theta}{n}+i \sin \frac{2 n \pi+\theta}{n}\right\} \\

\Rightarrow & z^{1 / n} =r^{1 / n}\left\{\cos \left(2 \pi+\frac{\theta}{n}\right)+i \sin \left(2 \pi+\frac{\theta}{n}\right)\right\} \\

\Rightarrow & z^{1 / n} =r^{1 / n}\left\{\cos \frac{\theta}{n}+i \sin \frac{\theta}{n}\right\}

\end{array}

\)

This is same as the value obtained by taking \(m=0\).

On taking \(m=n+1\), the value comes out to be identical with corresponding to \(m=1\).

Hence, \(z^{1 / n}\) has \(n\) distinct values.

We may use the following algorithm to find the \(n^{\text {th }}\) roots of a given complex number.

Algorithm

- Step I: Write the given complex number in polar form.

- Step II: Add \(2 m \pi\) to the argument.

- Step III: Apply De Moivre’s theorem.

- Step IV: Put \(m=0,1,2, \ldots,(n-1)\) i.e. one less than the number in the denominator of the given index in the lowest form.

Example 29: The number of roots of the equation \(z^6=-64\) whose real parts are non-negative, is

(a) 2

(b) 3

(c) 4

(d) 5

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& z^6=-64 \\

\Rightarrow & z=(-64)^{1 / 6} \\

\Rightarrow & z=2(-1)^{1 / 6} \\

\Rightarrow & z=2(\cos \pi+i \sin \pi)^{1 / 6} \\

\Rightarrow & z=2\{\cos (2 r \pi+\pi)+i \sin (2 r \pi+\pi)\}^{1 / 6}, r \in Z \\

\Rightarrow & z=2\left\{\cos (2 r+1) \frac{\pi}{6}+i \sin (2 r+1) \frac{\pi}{6}\right\}, r=0,1,2,3,4,5 \\

\Rightarrow & z=2\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}+\frac{i}{2}\right), 2 i, 2\left(\frac{-\sqrt{3}}{2}+\frac{i}{2}\right), \\

& 2\left(\frac{-\sqrt{3}}{2}-\frac{i}{2}\right),-2 i, 2\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}-\frac{i}{2}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Clearly, four of these complex numbers have non-negative real parts.

The \(\boldsymbol{n}^{\text {th }}\) Root of Unity

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { Let } z=1^{1 / n} . \\

& \Rightarrow \quad z=(\cos 0+i \sin 0)^{1 / n} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad z=(\cos 2 r \pi+i \sin 2 r \pi)^{1 / n}, \text { where } r \in Z \\

& \Rightarrow \quad z=\cos \frac{2 r \pi}{n}+i \sin \frac{2 r \pi}{n}, \text { where } r=0,1,2, \ldots,(n-1) \text { [Using De’Moivere’s Theorem] }

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad z=e^{\frac{i 2r \pi}{n}}, r=0,1,2, \ldots, n-1 \quad\left[\because e^{i \theta}=\cos \theta+i \sin \theta\right]

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad z=e^{\left(\frac{i 2 \pi}{n}\right)^{r}}, r=0,1,2, \ldots,(n-1)

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\Rightarrow \quad z=\alpha^{r}, \text { where } \alpha=e^{i 2 \pi / n}\\

&\text { Thus, } n \text {th roots of unity are: }\\

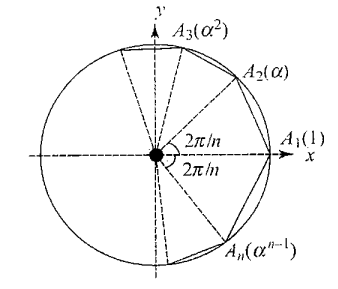

&1\left(=\alpha^0\right), \alpha, \alpha^2, \alpha^3, \ldots, \alpha^{n-1} \text {, where } \alpha=e^{i 2 \pi / n}=\cos 2 \pi / n+i \sin 2 \pi / n

\end{aligned}

\)

Properties of \(n^{\text {th }}\) Roots of Unity

Property 1: Sum of \(n^{\text {th }}\) roots of unity is always zero.

Proof: \(n\)th roots of unity are: \(1, \alpha, \alpha^2, \ldots, \alpha^{n-1}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\therefore \quad & 1+\alpha+\alpha^2+\ldots+\alpha^{n-1} \\

& =\frac{1-\alpha^n}{1-\alpha}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

=\frac{1-e^{i 2 \pi}}{1-\alpha} \left[\because \alpha=e^{i 2 \pi / n} \Rightarrow \alpha^n=e^{i 2 \pi}\right]

\)

\(

=\frac{1-1}{1-\alpha}=0 \quad\left[\because e^{i 2 \pi}=\cos 2 \pi+i \sin 2 \pi=1\right]

\)

Property 2: Product of \(n^{\text {th }}\) roots of unity is \((-1)^{n-1}\)

Proof: \(n^{\text {th }}\) roots of unity are : \(1, \alpha, \alpha^2, \ldots, \alpha^{n-1}\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

\therefore \quad \text { Product } & =1, \alpha \cdot \alpha^2 \ldots \alpha^{n-1} \\

& =\alpha^{1+2+3+\ldots+(n-1)} \\

& =\alpha^{n(n-1) / 2}=\left(\alpha^{n / 2}\right)^{n-1} \\

& =\left(e^{i \pi}\right)^{n-1} \quad\left[\because \alpha=e^{i 2 \pi / n} \Rightarrow \alpha^{n / 2}=e^{i \pi}\right] \\

& =(\cos \pi+i \sin \pi)^{n-1}=(-1)^{n-1}

\end{aligned}

\)

If \(n\) is even, the product is \((-1)^{n-1}\). If \(n\) is odd, the product is 1.

Note: The points represented by the \(n^{\text {th }}\) roots of unity are located at the vertices of a regular polygon of \(n\) sides inscribed in a unit circle having centre at the origin, one vertex being on the positive real axis (geometrically represented as shown).

Example 30: If \(z_1\) and \(z_2\) are two \(n^{\text {th }}\) roots of unity, then \(\arg \left(\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right)\) is a multiple of [CEE (Delhi) 2001]

(a) \(n \pi\)

(b) \(\frac{3 \pi}{n}\)

(c) \(\frac{2 \pi}{n}\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

z_1=e^{i 2r \pi / n} \text { and } z_2=e^{i 2s \pi / n},

\)

where \(r\) and \(s\) are integers lying between 0 and \(n\), including 0 and \(n\).

\(

\therefore \quad \arg \left(\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right)=\frac{2 r \pi}{n}-\frac{2 s \pi}{n}=2(r-s) \frac{\pi}{n}

\)

Clearly, \(\arg \left(\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right)\) is a multiple of \(\frac{2 \pi}{n}\)

Example 31: If \(1, \alpha_1, \alpha_2, \ldots, \alpha_{n-1}\) are \(n^{\text {th }}\) roots of unity, then the value of \(\left(1-\alpha_1\right)\left(1-\alpha_2\right)\left(1-\alpha_3\right) \ldots\left(1-\alpha_{n-1}\right)\) is equal to [CEE (Delhi) 1997, 2001, 2006]

(a) \(\sqrt{3}\)

(b) \(1 / 2\)

(c) \(n\)

(d) 0

Solution: (c) It is given that \(1, \alpha_1, \alpha_2, \ldots, \alpha_{n-1}\) are \(n^{\text {th }}\) roots of unity.

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & x^n-1=(x-1)\left(x-\alpha_1\right)\left(x-\alpha_2\right) \ldots\left(x-\alpha_{n-1}\right) \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{x^n-1}{x-1}=\left(x-\alpha_1\right)\left(x-\alpha_2\right) \ldots\left(x-\alpha_{n-1}\right) \\

\Rightarrow & 1+x+x^2+\ldots+x^{n-1}=\left(x-\alpha_1\right)\left(x-\alpha_2\right) \ldots\left(x-\alpha_{n-1}\right)

\end{array}

\)

Putting \(x=1\) on both sides, we get

\(

\left(1-\alpha_1\right)\left(1-\alpha_2\right) \ldots\left(1-\alpha_{n-1}\right)=n .

\)

Example 32: If \(\alpha\) is an \(n^{\text {th }}\) root of unity, then \(1+2 \alpha+3 \alpha^2+\ldots+n \alpha^{n-1}\) equals

(a) \(\frac{n}{1-\alpha}\)

(b) \(-\frac{n}{1-\alpha}\)

(c) \(-\frac{n}{(1-\alpha)^2}\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) Let \(S=1+2 \alpha+3 \alpha^2+\ldots+n \cdot \alpha^{n-1}\). Then,

\(

\alpha S=\alpha+2 \alpha^2+3 \alpha^3+\ldots+(n-1) \alpha^{n-1}+n \alpha^n

\)

\(

\therefore \quad S-\alpha S=\left(1+\alpha+\alpha^2+\ldots+\alpha^{n-1}\right)-n \alpha^n

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad S(1-\alpha)=\frac{\alpha^n-1}{\alpha-1}-n \alpha^n

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\Rightarrow \quad S(1-\alpha)=\frac{1-1}{\alpha-1}-n\\

&\left[\because \alpha^n=1\right]

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad S=-\frac{n}{(1-\alpha)}

\)

Example 33: If \(\omega\) is an imaginary fifth root of unity, then find the value of \(\log _2\left|1+\omega+\omega^2+\omega^3-1 / \omega\right|\).

Solution: Step 1: Simplify the sum of the first four terms

For an imaginary fifth root of unity \(\omega\), it satisfies the equation \(\omega^5=1\) and the sum of all fifth roots is zero:

\(

1+\omega+\omega^2+\omega^3+\omega^4=0

\)

Rearranging this equation gives:

\(

1+\omega+\omega^2+\omega^3=-\omega^4

\)

Step 2: Simplify the last term and the full expression

Since \(\omega^5=1\), we can write \(1 / \omega\) as \(\omega^4\) :

\(

1 / \omega=\omega^4 / \omega^5=\omega^4 / 1=\omega^4

\)

The expression inside the absolute value becomes:

\(

\left(1+\omega+\omega^2+\omega^3\right)-1 / \omega=-\omega^4-\omega^4=-2 \omega^4

\)

Step 3: Calculate the modulus

The modulus of \(-2 \omega^4\) is:

\(

\left|-2 \omega^4\right|=|-2| \cdot\left|\omega^4\right|=2 \cdot|\omega|^4

\)

Since \(\omega\) is a root of unity, its modulus \(|\omega|\) is 1.

\(

\left|-2 \omega^4\right|=2 \cdot 1^4=2

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { The value we need to find is } \log _2\left(\left|-2 \omega^4\right|\right) \text {, which simplifies to } \log _2(2) \text {. }\\

&\log _2(2)=1

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 34: If \(1, z_1, z_2, z_3, \ldots, z_{n-1}\) are the \(n^{\text {th }}\) roots of unity, then prove that \(\left(1-z_1\right)\left(1-z_2\right) \cdots\left(1-z_{n-1}\right)=n\).

Solution: \(z^n-1=(z-1)\left(z-z_1\right)\left(z-z_2\right) \cdots\left(z-z_{n-1}\right)\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \frac{z^n-1}{z-1}=\left(z-z_1\right)\left(z-z_2\right) \cdots\left(z-z_{n-1}\right) \\

& \Rightarrow 1+z+z^2+\cdots+z^{n-1}=\left(z-z_1\right)\left(z-z_2\right) \cdots\left(z-z_{n-1}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Putting \(z=1\), we get

\(

\left(1-z_1\right)\left(1-z_2\right) \cdots\left(1-z_{n-1}\right)=1+1+\cdots+1=n

\)

Example 35: If \(\alpha=e^{i 2 \pi / 7}\) and \(f(x)=a_0+\sum_{k=1}^{20} a_k x^k\), then prove that the value of \(f(x)+f(\alpha x)+\cdots+f\left(\alpha^6 x\right)\) is independent of \(\alpha\).

Solution: \(\alpha=e^{i 2 \pi / 7}=7^{\text {th }}\) root of unity or root of the equation \(z^7-1=0\). Its other roots are \(1, \alpha^2, \alpha^3, \alpha^4, \alpha^5, \alpha^6\). Now,

\(

f(x)+f(\alpha x)+\cdots+f\left(\alpha^6 x\right)

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =7 a_0+\sum_{k=1}^{20} a_k x^k+\sum_{k=1}^{20} a_k(\alpha x)^k+\cdots+\sum_{k=1}^{20} a_k\left(\alpha^6 x\right)^k \\

& =7 a_0+\sum_{k=1}^{20} a_k\left(x^k+\alpha^k x^k+\alpha^{2 k} x^k+\cdots+\alpha^{6 k} x^k\right) \\

& =7 a_0+\sum_{k=1}^{20} a_k\left(x^k+\alpha^k x^k+\alpha^{2 k} x^k+\cdots+\alpha^{6 k} x^k\right) \\

& =7 a_0+\sum_{k=1}^{20} a_k\left(x^k \frac{\left(\alpha^k\right)^7-1}{\alpha^k-1}\right) \\

& =7 a_0+\sum_{k=1}^{20} a_k\left(x^k \frac{\left(\alpha^7\right)^k-1}{\alpha^k-1}\right) \\

& =7 a_0+\sum_{k=1}^{20} a_k\left(x^k \frac{1-1}{\alpha^k-1}\right) \\

& =7 a_0 \quad \quad\left(\because \alpha \text { is a root of } z^7-1=0 \Rightarrow \alpha^7-1=0\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Cube Roots Of Unity

Note that the cube roots of unity follow all the properties listed for \(n\)th roots of unity, but due to their importance, we shall list the properties of cube be roots of unity separately in the following section.

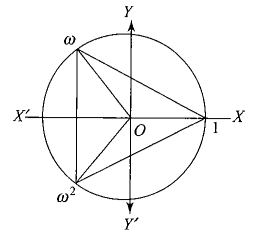

As discussed in the previous section that the cube roots of unity are \(1, \omega\) and \(\omega^2\), where

\(

\omega=e^{i 2 \pi / 3}=-\frac{1}{2}+i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \text { and } \omega^2=e^{i 4 \pi / 3}=-\frac{1}{2}-i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} .

\)

We shall now obtain cube roots of unity by an alternative method.

Let \(z=1^{1 / 3}\). Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& z^3=1 \\

\Rightarrow & z^3-1=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (z-1)\left(z^2+z+1\right)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & z=1, z^2+z+1=0 \\

\Rightarrow & z=1, z=\frac{-1 \pm i \sqrt{3}}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus, cube roots of unity are \(1, \frac{-1+i \sqrt{3}}{2}\) and \(\frac{-1-i \sqrt{3}}{2}\).

Clearly, one of the roots of unity is real and the other two are complex.

It can be easily seen that \(-\frac{1}{2}+i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) and \(-\frac{1}{2}-i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) are complex numbers of unit modulus such that

\(\arg \left(-\frac{1}{2}+i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)=\frac{2 \pi}{3}\) and \(\arg \left(-\frac{1}{2}-i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)=\frac{4 \pi}{3}\).

\(

\therefore \quad-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{i \sqrt{3}}{2}=e^{i 2 \pi / 3} \text { and }-\frac{1}{2}-\frac{i \sqrt{3}}{2}=e^{i 4 \pi / 3}

\)

Let \(\omega=e^{i 2 \pi / 3}\). Then, \(\omega^2=e^{i 4 \pi / 3}\)

Thus, cube roots of unity are \(1, \omega, \omega^2\), where \(\omega=e^{i 2 \pi / 3}\)

Properties of Cube Roots of Unity

- Property 1: Cube roots of unity are \(1, \omega, \omega^2\), where \(\omega=-\frac{1}{2} \pm i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}=e^{i 2 \pi / 3}\)

- Property 2: \(\arg (\omega)=\frac{2 \pi}{3}\) and \(\arg \left(w^2\right)=\frac{4 \pi}{3}\)

- Property 3: \(z^3-1=(z-1)(z-\omega)\left(z-\omega^2\right)\)

- Property 4: The sum of three cube roots of unity is zero, i.e., \(1+\omega+\omega^2=0\).

- Property 5: \(\omega\) and \(\omega^2\) are roots of the equation \(z^2+z+1=0\)

- Property 6: The product of three cube roots of unity is 1.

Proof:

Three cube roots of unity are \(1, \omega\) and \(\omega^2\). So, product of cube roots of unity is \(1 \times \omega \times \omega^2=\omega^3=1\). - Property 7: Each complex cube root of unity is the reciprocal of the other.

Proof:

We have,

\(

\omega \times \omega^2=\omega^3=1 \Rightarrow \omega=\frac{1}{\omega^2} \text { and } \omega^2=\frac{1}{\omega}

\) - Property 8: Cube roots of -1 are \(-1,-\omega\) and \(-\omega^2\).

Proof:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& z=(-1)^{1 / 3} \\

\Rightarrow & z^3=-1 \\

\Rightarrow & (-z)^3=1

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad-z=1, \omega, \omega^2 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad z=-1,-\omega,-\omega^2

\end{aligned}

\) - Property 9: Integral powers of \(\boldsymbol{\omega}\)

Since \(\omega\) is a root of the equation \(z^3-1=0\), so, it satisfies the equation \(z^3-1=0\). Therefore,

\(

\omega^3-1=0 \Rightarrow \omega^3=1

\)

Since \(\omega^3=1\), therefore \(\omega^n=\omega^r\), where \(r\) is the least nonnegative remainder obtained by dividing \(n\) by 3. For example, \(\omega^{18}=\left(\omega^3\right)^6=1^6=1, \omega^{20}=\left(\omega^3\right)^6 \omega^2=1^6 \omega^2=\omega^2, \omega^{-30}=\left(\omega^3\right)^{-10}= 1^{-10}=1, \omega^{28}=\left(\omega^{27}\right) \omega=\omega\). - Property 10: Cube roots of unity lie on the unit circle \(|z|=1\) and divide its circumference into three equal parts.

- Property 11: If \(1, \omega, \omega^2\) be cube roots of unity and \(n\) is a positive integer, then

\(

1+\omega^n+\omega^{2 n}= \begin{cases}3, & \text { when } n \text { is a multiple of } 3 \\ 0, & \text { when } n \text { is not a multiple of } 3\end{cases}

\) - Property 12: \(z^3+1=(z+1)(z+\omega)\left(z+\omega^2\right)\)

- Property 13: \(-\omega\) and \(-\omega^2\) are roots of \(z^2-z+1=0\)

- Property 14: Factorization of \(a^3+b^3\) and \(a^3-b^3\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

a^3+b^3 & =(a+b)\left(a^2-a b+b^2\right) \\

& =(a+b)(a+b \omega)\left(a+b \omega^2\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

and

\(

\begin{aligned}

a^3-b^3 & =(a-b)\left(a^2+a b+b^2\right) \\

& =(a-b)(a-b \omega)\left(a-b \omega^2\right)

\end{aligned}

\) - Property 15:

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Factorization of } a^3+b^3+c^3-3 a b c\\

&\begin{array}{r}

a^3+b^3+c^3-3 a b c=(a+b+c)\left(a^2+b^2+c^2-a b-b c\right. \\

-c a)=(a+b+c)\left(a+b \omega+c \omega^2\right)\left(a+b \omega^2+c \omega\right)

\end{array}

\end{aligned}

\) - Property 16: \(a^2+b^2+c^2-a b-b c-c a=\left(a+b \omega+c \omega^2\right)\left(a+b \omega^2+c \omega\right)\)

- Cube roots of unity represent vertices of equilateral triangle on the Argand plane.

Example 36: The roots of the equation \((x-1)^3+8=0\) are [AIEEE 2005]

(a) \(-1,1+2 w, 1+2 w^2\)

(b) \(-1,1-2 w, 1-2 w^2\)

(c) \(2,2 w, 2 w^2\)

(d) \(2,1+2 w, 1+2 w^2\)

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (x-1)^3+8=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (x-1)^3=-8 \\

\Rightarrow & (x-1)=(-8)^{1 / 3} \\

\Rightarrow & x-1=-2,-2 w,-2 w^2 \Rightarrow x=-1,1-2 w, 1-2 w^2

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 37: The argument of \(\frac{1-i \sqrt{3}}{1+i \sqrt{3}}\) is

(a) \(\frac{\pi}{3}\)

(b) \(\frac{2 \pi}{3}\)

(c) \(\frac{7 \pi}{6}\)

(d) \(\frac{4 \pi}{3}\)

Solution: (d) Step 1: Convert numerator and denominator to polar form

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 1-i \sqrt{3}=2\left(\frac{1}{2}-i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)=2 e^{-i \pi / 3} \\

& 1+i \sqrt{3}=2\left(\frac{1}{2}+i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)=2 e^{i \pi / 3}

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 2: Form the quotient

\(

z=\frac{2 e^{-i \pi / 3}}{2 e^{i \pi / 3}}=e^{-i \pi / 3} e^{-i \pi / 3}=e^{-2 \pi i / 3} .

\)

But \(-\frac{2 \pi}{3}\) corresponds to the same direction as:

\(

\frac{4 \pi}{3}(\text { add } 2 \pi) .

\)

Thus

\(

\arg (z)=\frac{4 \pi}{3} .

\)

Let \(\omega=e^{2 \pi i / 3}\), so \(\omega^2=e^{4 \pi i / 3}\).

Correct identities:

\(

1-i \sqrt{3}=-2 \omega, \quad 1+i \sqrt{3}=-2 \omega^2 .

\)

Therefore:

\(

z=\frac{-2 \omega}{-2 \omega^2}=\frac{\omega}{\omega^2}=\omega^{-1}=\omega^2 .

\)

Hence:

\(

\arg (z)=\arg \left(\omega^2\right)=\frac{4 \pi}{3} .

\)

Note:

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { For cube roots of unity, }\\

&\omega^3=1 .\\

&\omega^{-1}=\frac{1}{\omega}=\omega^{3-1}=\omega^2 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Since

\(

\omega=e^{2 \pi i / 3},

\)

then

\(

\omega^{-1}=e^{-2 \pi i / 3} .

\)

But adding \(2 \pi\) :

\(

e^{-2 \pi i / 3}=e^{4 \pi i / 3}=\omega^2 .

\)

Example 38: If \(\omega\) is an imaginary cube root of unity, then \(\left(1+\omega-\omega^2\right)^7\) equals [IIT 1998]

(a) \(128 \omega\)

(b) \(-128 \omega\)

(c) \(128 \omega^2\)

(d) \(-128 \omega^2\)

Solution: (d) We have,

\(

\left(1+\omega-\omega^2\right)^7=\left(-2 \omega^2\right)^7=-128 \omega^2

\)

Explanation:

\(

1+\omega-\omega^2 .

\)

Substitute \(\omega^2=-1-\omega\) :

\(

1+\omega-(-1-\omega)=1+\omega+1+\omega=2+2 \omega=2(1+\omega) .

\)

Next, simplify \(1+\omega\) :

From

\(

1+\omega+\omega^2=0

\)

we get

\(

1+\omega=-\omega^2 .

\)

Thus:

\(

1+\omega-\omega^2=2(1+\omega)=2\left(-\omega^2\right)=-2 \omega^2

\)

\(

\left(1+\omega-\omega^2\right)^7=\left(-2 \omega^2\right)^7 =-128 \omega^2 .

\)

Example 39: When the polynomial \(5 x^3+M x+N\) is divided by \(\boldsymbol{x}^{\mathbf{2}} \boldsymbol{+} \boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{+} \mathbf{1}\), the remainder is \(\mathbf{0}\). Then find the value of \(M+N\).

Solution: Let \(f(x)=5 x^3+M x+N\).

Also, \(x^2+x+1=(x-\omega)\left(x-\omega^2\right)\)

\(f(x)\) is divisible by \(x^2+x+1\). Hence, \(f(\omega)=5+M \omega+N=0\)

and

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f\left(\omega^2\right)=5+M \omega^2+N=0 \\

\Rightarrow & M=0 ; N=-5 \\

\Rightarrow & M+N=-5

\end{aligned}

\)

Explanation:

Let

\(

f(x)=5 x^3+M x+N

\)

and suppose the remainder is \(\mathbf{0}\) when divided by

\(

x^2+x+1=0 .

\)

The roots of \(x^2+x+1\) are the complex cube roots of unity:

\(

\omega, \omega^2, \quad \omega^3=1, \omega \neq 1 .

\)

Since the remainder is zero,

\(

f(\omega)=0, \quad f\left(\omega^2\right)=0 .

\)

Because \(\omega^3=1\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

f(\omega)=5 \omega^3+M \omega+N=5+M \omega+N=0 \dots(1) \\

f\left(\omega^2\right)=5 \omega^3+M \omega^2+N=5+M \omega^2+N=0 \dots(2)

\end{gathered}

\)

Subtract (1)-(2):

\(

M\left(\omega-\omega^2\right)=0 .

\)

But \(\omega \neq \omega^2\), so:

\(

M=0 .

\)

Substitute into (1):

\(

5+N=0 \quad \Rightarrow \quad N=-5 .

\)

\(M+N=-5\)

Example 40: If \(\omega\) and \(\omega^2\) are the non-real cube roots of unity and \([1 /(a+\omega)]+[1 /(b+\omega)]+[1 /(c+\omega)]=2 \omega^2\) and \(\left[1 /(a+\omega)^2\right]+\left[1 /(b+\omega)^2\right]+\left[1 /(c+\omega)^2\right]=2 \omega\), then find the value of \([1 /(a+1)]+[1 /(b+1)]+[1 /(c+1)]\).

Solution: The given relations can be rewritten as

\(

\frac{1}{a+\omega}+\frac{1}{b+\omega}+\frac{1}{c+\omega}=\frac{2}{\omega}

\)

and

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{1}{a+\omega^2}+\frac{1}{b+\omega^2}+\frac{1}{c+\omega^2}=\frac{2}{\omega^2} \\

\Rightarrow & \omega \text { and } \omega^2 \text { are roots of } \frac{1}{a+x}+\frac{1}{b+x}+\frac{1}{c+x}=\frac{2}{x} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{3 x^2+2(a+b+c) x+b c+c a+a b}{(a+x)(b+x)(c+x)}=\frac{2}{x} \\

\Rightarrow & x^3+(b c+c a+a b) x-2 a b c=0 \dots(1)

\end{aligned}

\)

Two roots of the Eq. (1) are \(\omega\) and \(\omega^2\). Let the third root be \(\alpha\). Then,

\(

\alpha+\omega+\omega^2=0 \Rightarrow \alpha=-\omega-\omega^2=1

\)

Therefore, \(\alpha=1\) will satisfy Eq. (1). Hence,

\(

\frac{1}{a+1}+\frac{1}{b+1}+\frac{1}{c+1}=2

\)

Example 41: If \(w(\neq 1)\) be a cube root of unity and \(\left(1+w^2\right)^n =\left(1+w^4\right)^n\), then the least positive value of \(n\), is [JEE (WB) 2007, IIT (S) 2004]

(a) 2

(b) 3

(c) 5

(d) 6

Solution: Step 1: Utilize properties of cube roots of unity

We are given that \(w \neq 1\) is a cube root of unity, which implies two key properties: \(w^3=1\) and \(1+w+w^2=0\). The second property can be rewritten as \(1+w^2=-w\) and \(1+w=-w^2\). Also, \(w^4=w^3 \cdot w=1 \cdot w=w\).

Step 2: Substitute properties into the given equation

The given equation is \(\left(1+w^2\right)^n=\left(1+w^4\right)^n\). Substituting the properties from Step 1, we get:

\(

(-w)^n=\left(-w^2\right)^n

\)

Step 3: Simplify the equation

Expanding both sides of the equation:

\(

\begin{gathered}

(-1)^n w^n=(-1)^n\left(w^2\right)^n \\

(-1)^n w^n=(-1)^n w^{2 n}

\end{gathered}

\)

Dividing both sides by the non-zero term \((-1)^n\) :

\(

w^n=w^{2 n}

\)

Rearranging the terms:

\(

w^{2 n}-w^n=0

\)

Factoring out \(w^n\) :

\(

w^n\left(w^n-1\right)=0

\)

Step 4: Solve for \(\mathbf{n}\)

Since \(w\) is a non-zero complex number, \(w^n \neq 0\). Therefore, the equation requires \(w^n-1=0\), which means \(w^n=1\).

For \(w^n=1\) to hold true for the primitive cube root of unity \(w, n\) must be a positive integer that is a multiple of 3. The possible values for \(n\) are \(3,6,9, \ldots\) The least positive value of \(n\) is 3.

Explanation: A primitive cube root of unity is:

\(

w=e^{2 \pi i / 3} \quad \text { or } \quad w=e^{4 \pi i / 3} .

\)

Both satisfy:

\(

w^3=1, \quad w \neq 1 .

\)

The powers of \(w\) cycle every 3 steps:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& w^1=w \\

& w^2=w^2 \\

& w^3=1 \\

& w^4=w \\

& w^5=w^2 \\

& w^6=1 \\

& \text { etc. }

\end{aligned}

\)

This sequence repeats with period 3.

Step 2: When does \(w^n=1\) happen?

From the cycle:

\(

w^n=1 \quad \text { exactly when } n=3 k .

\)

That is:

\(w^3=1\)

\(w^6=1\)

\(w^9=1\)

and so on…

So the allowed values of \(n\) are:

\(

n=3,6,9,12, \ldots

\)

These are exactly the multiples of 3.

Among 3, 6, 9, 12, . . ., the least positive number is:3.

Example 42: If \(i=\sqrt{-1}\), then \(4+5\left(-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{i \sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^{334}+3\left(-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{i \sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^{365}\) is equal to [IIT 1999]

(a) \(1-i \sqrt{3}\)

(b) \(-1+i \sqrt{3}\)

(c) \(i \sqrt{3}\)

(d) \(-i \sqrt{3}\)

Solution: (c)

We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 4+5\left(-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{i \sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^{334}+3\left(-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{i \sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^{365} \\

& =4+5 \omega^{334}+3 \omega^{365}=4+5 \omega+3 \omega^2 \\

& =4+5\left(-\frac{1}{2}+i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)+3\left(-\frac{1}{2}-i \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)=i \sqrt{3}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 43: If \(z(2-2 \sqrt{3} i)^2=i(\sqrt{3}+i)^4\), then \(\arg (z)=\)

(a) \(\frac{5 \pi}{6}\)

(b) \(-\frac{\pi}{6}\)

(c) \(\frac{\pi}{6}\)

(d) \(\frac{7 \pi}{6}\)

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& & z(2-2 \sqrt{3} i)^2 & =i(\sqrt{3}+i)^4 \\

\Rightarrow & & 4 z(1-i \sqrt{3})^2 & =i^5(1-i \sqrt{3})^4 \\

\Rightarrow & & 4 z & =i(1-i \sqrt{3})^2 \\

\Rightarrow & & 4 z & =i(-2 \omega)^2=4 i \omega^2 \Rightarrow z=i \omega^2=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}-\frac{1}{2} i

\end{aligned}

\)

Clearly, \(\arg (z)=-\frac{\pi}{6}\)

Alternate: We have,

\(

z=i \omega^2 \Rightarrow \arg (z)=\arg (i)+\arg \left(\omega^2\right)=\frac{\pi}{2}-\frac{2 \pi}{3}=-\frac{\pi}{6}

\)

Example 44: If \(\omega\) is a complex cube root of unity, then

\(

\arg (i \omega)+\arg \left(i \omega^2\right)=

\)

(a) 0

(b) \(\pi / 2\)

(c) \(\pi\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \arg (\omega)=\frac{2 \pi}{3} \text { and } \arg \left(\omega^2\right)=\frac{4 \pi}{3} \text { or, } \arg \left(\omega^2\right)=-\frac{2 \pi}{3} \\

\therefore \quad & \arg (i \omega)+\arg \left(i \omega^2\right)=\arg (i)+\arg (\omega)+\arg (i)+\arg \left(\omega^2\right) \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \arg (i \omega)+\arg \left(i \omega^2\right)=\frac{\pi}{2}+\frac{2 \pi}{3}+\frac{\pi}{2}-\frac{2 \pi}{3}=\pi

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 45: If \(w\) is an imaginary cube root of unity, then the value of the expression

\(1 \cdot(2-\omega)\left(2-\omega^2\right)+2 \cdot(3-\omega)\left(3-\omega^2\right)+\ldots \ldots +(n-1)(n-\omega)\left(n-\omega^2\right)\), is [IIT 1996].

(a) \(\left\{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right\}^2\)

(b) \(\left\{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right\}^2-n\)

(c) \(\left\{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right\}^2+n\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (z-1)(z-\omega)\left(z-\omega^2\right)=z^3-1 \\

\therefore \quad & 1(2-\omega)\left(2-\omega^2\right)+2(3-\omega)\left(3-\omega^2\right)+\ldots+(n-1)(n-\omega)\left(n-\omega^2\right) \\

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

=\sum_{r=2}^n(r-1)(r-\omega)\left(r-\omega^2\right)

\)

\(

=\sum_{r=2}^n\left(r^3-1\right)=\sum_{r=2}^n r^3-\sum_{r=2}^n 1=\left(\sum_{r=1}^n r^3\right)-1-\left(\sum_{r=2}^n 1\right)

\)

\(

=\left\{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right\}^2-1-(n-1)=\left\{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right\}^2-n

\)

Example 46: If \(z^2+z+1=0\), where \(z\) is a complex number, then the value of

\(\left(z+\frac{1}{z}\right)^2+\left(z^2+\frac{1}{z^2}\right)^2+\left(z^3+\frac{1}{z^3}\right)^2+\ldots .+\left(z^6+\frac{1}{z^6}\right)^2 \text { is }\) [AIEEE 2006]

(a) 54

(b) 6

(c) 12

(d) 18

Solution: (c) We know that \(w\) and \(w^2\) are roots of \(z^2+z+1=0\) such that \(w=\frac{1}{w^2}\). So, the value of the given expression remains same for \(z=w\) and, \(z=\frac{1}{w^2}\). Also, \(1+w+w^2=0\) and \(w^3=1\).

Putting \(z=w\), we have

\(

\left(z+\frac{1}{z}\right)^2+\left(z^2+\frac{1}{z^2}\right)+\left(z^3+\frac{1}{z^3}\right)^2+\ldots+\left(z^6+\frac{1}{z^6}\right)^2

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

=\left\{\left(z+\frac{1}{z}\right)^2+\left(z^2+\frac{1}{z^2}\right)^2+\left(z^4+\frac{1}{z^4}\right)^2\right. & +\left(z^5+\frac{1}{z^5}\right)^2 \\

& +\left\{\left(z^3+\frac{1}{z^3}\right)^2+\left(z^6+\frac{1}{z^6}\right)^2\right\}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

=4\left(w+w^2\right)^2+\left(2^2+2^2\right)=4+8=12

\)

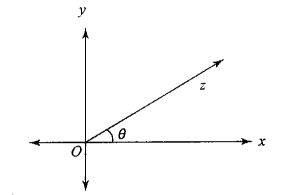

Vectorial Representation of a Complex Number

A complex number \(z=x+i y\) can be represented by the position vector \(O P\) of point \(P(x, y)\) in a two dimensional plane because a complex number depends on two things viz. (i) its modulus and (ii) its argument which are also the requirements of a vector on a plane.

In Figure below, the complex number \(z=x+i y\) is represented by the vector \(\overrightarrow{O P}\) and in such a case \(|z|\) is the length \(O P\) and \(\arg (z)\) is the angle which the directed line \(O P\) makes with the positive direction of \(x\)-axis.

Polar or Trigonometrical Form of a Complex Number

Let \(z=x+i y\) be a complex number represented by a point \(P(x, y)\) in the Argand plane. Then, by the geometrical representation of \(z=x+i y\), we have

\(

O P=|z| \text { and } \angle P O X=\theta=\arg (z)

\)

In \(\triangle P O M\), we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \cos \theta=\frac{O M}{O P}=\frac{x}{|z|} \text { and, } \sin \theta=\frac{P M}{O P}=\frac{y}{|z|} \\

\Rightarrow & x=|z| \cos \theta \text { and, } y=|z| \sin \theta \\

\therefore & z=x+i y \\

\Rightarrow & z=|z| \cos \theta+i|z| \sin \theta \\

\Rightarrow & z=|z|(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta) \\

\Rightarrow & z=r(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta), \text { where } r=|z| \text { and } \theta=\arg (z)

\end{aligned}

\)

This form of \(z\) is called a polar form of \(z\). If we use the general value of the argument of \(\theta\), then the polar form of \(z\) is

\(

z=r[\cos (2 n \pi+\theta)+i \sin (2 n \pi+\theta)] \text {, where }

\)

\(r=|z|, \theta=\arg (z)\) and \(n\) is an integer.

Example 47: The amplitude of \(\sin \frac{\pi}{5}+i\left(1-\cos \frac{\pi}{5}\right)\), is [CEE (Delhi) 2008]

(a) \(\frac{2 \pi}{5}\)

(b) \(\frac{\pi}{15}\)

(c) \(\frac{\pi}{10}\)

(d) \(\frac{\pi}{5}\)

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

z & =\sin \frac{\pi}{5}+i\left(1-\cos \frac{\pi}{5}\right)=2 \sin \frac{\pi}{10} \cos \frac{\pi}{10}+2 i \sin ^2 \frac{\pi}{10} \\

\Rightarrow \quad z & =2 \sin \frac{\pi}{10}\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{10}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{10}\right) \\

\Rightarrow|z| & =2 \sin \frac{\pi}{10} \text { and } \arg (z)=\frac{\pi}{10}

\end{aligned}

\)

Eulerian Form Of a Complex Number

We have,

\(

e^{i \theta}=\cos \theta+i \sin \theta \text { and } e^{-i \theta}=\cos \theta-i \sin \theta

\)

These two are called Euler’s notations.

Let \(z\) be any complex number such that \(|z|=r\) and \(\arg (z)=\theta\).

Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

z & =r(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta) \\

\Rightarrow \quad z & =r e^{i \theta}

\end{aligned}

\)

[Using Euler’s notations]

This form of \(z\) is known as the Eulerian form.

For example, if \(z=1+i\), then \(|z|=\sqrt{2}\) and \(\arg (z)=\pi / 4\)

\(

\therefore \quad z=\sqrt{2} e^{i \pi / 4}

\)

Similarly, we have

\(

-2+2 i=2 \sqrt{2} e^{i 3 \pi / 4} \text { and }-1-i \sqrt{3}=2 e^{i 4 \pi / 3}

\)

Some Important Results on Modulus and Argument

Theorem: Let \(z_1 z_1\) and \(z_2\) be complex numbers, with arguments \(\theta_1\) and \(\theta_2\) respectively. Then,

- \(\arg (z)=-\arg (z)\)

- \(\arg \left(z_1 z_2\right)=\arg \left(z_1\right)+\arg \left(z_2\right)\)

- \(\arg \left(z_1 \bar{z}_2\right)=\arg \left(z_1\right)-\arg \left(z_2\right)\)

- \(\arg \left(z_1 / z_2\right)=\arg \left(z_1\right)-\arg \left(z_2\right)\)

- \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|^2=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2+2\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| \cos \left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)\)

or \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|^2=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2+2 \operatorname{Re}\left(z_1 \bar{z}_2\right)\) - \(\left|z_1-z_2\right|^2=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2-2\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| \cos \left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)\)

or \(\left|z_1-z_2\right|^2=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2-2 \operatorname{Re}\left(z_1 \bar{z}_2\right)\) - \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|^2+\left|z_1-z_2\right|^2=2\left(\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2\right)\)

- \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|=\left|z_1-z_2\right| \Leftrightarrow \arg \left(z_1\right)-\arg \left(z_2\right)=\pi / 2\)

- \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|=\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right| \Leftrightarrow \arg \left(z_1\right)=\arg \left(z_2\right)\)

- \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|^2=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2 \Leftrightarrow \frac{z_1}{z_2}\) is purely imaginary.

- \(\left|z_1+z_2\right| \leq\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right|\)

- \(\left|z_1-z_2\right| \leq\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right| \text { [Triangle inequalities] }\)

- \(\left|z_1+z_2\right| \geq\left|z_1\right|-\left|z_2\right|\)

- \(\left|z_1-z_2\right| \geq\left|z_1\right|-\left|z_2\right|\)

Example 49: Let \(z_1, z_2\) be two complex numbers such that \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|=\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right|\). Then, [JEE (WB) 2008]

(a) \(\arg \left(z_1\right)=\arg \left(z_2\right)\)

(b) \(\arg \left(z_1\right)+\arg \left(z_2\right)=\frac{\pi}{2}\)

(c) \(\left|z_1\right|=\left|z_2\right|\)

(d) \(z_1 z_2=1\)

Solution: (a) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left|z_1+z_2\right|=\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right| \\

\Rightarrow & \left|z_1+z_2\right|^2=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2+2\left|z_2\right|\left|z_1\right| \\

\Rightarrow & 2\left|z_1\right|\left|\bar{z}_2\right| \cos \left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)=2\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right|

\end{aligned}

\)

where \(\theta_1=\arg \left(z_1\right), \theta_2=\arg \left(z_2\right)\)

\(

\Rightarrow \cos \left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)=1 \Rightarrow \theta_1-\theta_2=0 \Rightarrow \arg \left(\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right)=0

\)

Example 50: If \(z_1, z_2\) be any two non-zero complex numbers such that \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|=\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right|\), then \(\arg \left(z_1\right)-\arg \left(z_2\right)\) is equal to [AIEEE 2005]

(a) \(-\pi\)

(b) \(-\pi / 2\)

(c) 0

(d) \(\pi / 2\)

Solution: (c) Let \(z_1=r_1\left(\cos \theta_1+i \sin \theta_1\right), z_2=r_2\left(\cos \theta_2+i \sin \theta_2\right)\).

Then, \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|=\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right|\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad r_1^2+r_2^2+2 r_1 r_2 \cos \left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)=r_1^2+r_2^2+2 r_1 r_2 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \cos \left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)=1 \Rightarrow \theta_1-\theta_2=0 \Rightarrow \arg \left(z_1\right)-\arg \left(z_2\right)=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 51: If \(|z+4| \leq 3\), then the maximum value of \(|z+1|\) is [AIEEE 2007]

(a) 6

(b) 0

(c) 4

(d) 10

Solution: (a) We have,

\(

|z+1|=|(z+4)-3| \leq|z+4|+|3|\left[\begin{array}{r}

\because\left|z_1-z_2\right| \\

\leq\left|z_1\right|+\left|z_2\right|

\end{array}\right]

\)

\(

\Rightarrow|z+1| \leq 3+3=6

\)

Example 52: If \(|z|<\sqrt{2}-1\), then \(\left|z^2+2 z \cos \alpha\right|\) is less than [CEE (Delhi) 2001]

(a) 1

(b) \(\sqrt{2}+1\)

(c) \(\sqrt{2}-1\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (a) We have,

\(

\begin{array}{rlrl}

& \left|z^2+2 z \cos \alpha\right| \leq\left|z^2\right|+|2 z \cos \alpha| \\

\Rightarrow & \left|z^2+2 z \cos \alpha\right| \leq|z|^2+2|z||\cos \alpha| \\

\Rightarrow & \left|z^2+2 z \cos \alpha\right| \leq|z|^2+2|z| \\

\Rightarrow & \left|z^2+2 z \cos \alpha\right|<(\sqrt{2}-1)^2+2(\sqrt{2}-1) \\

\Rightarrow & \left|z^2+2 z \cos \alpha\right|<1

\end{array}

\)