5.8 Entrance Corner (Quadratic in Graphs)

Geometrical Meaning of Roots (Zeros) of an Equation

We know that that a real number \(k\) is a zero of the polynomial \(f(x)\) if \(f(k)=0\). But why are the zeroes of a polynomial so important? To answer this, first we will see the geometrical representations of polynomials and the geometrical meaning of their zeroes.

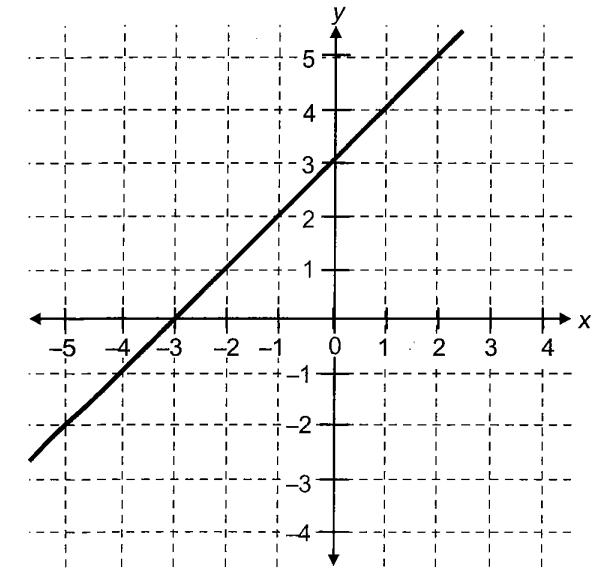

We know that graph of the linear function \(y=f(x)=a x+b\) is a straight line.

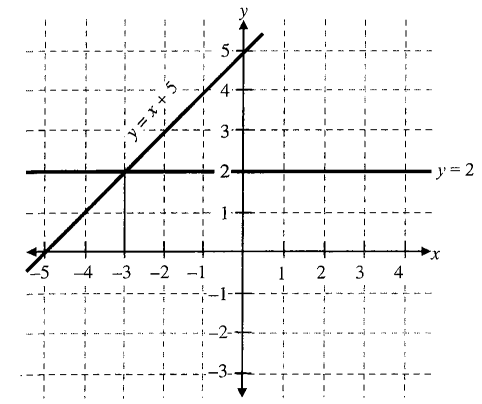

Illustration 1: Consider the function \(f(x)=x+3\).

Now we can see that this graph cuts the \(x\)-axis at \(x=-3\), where value of \(y=0\) or we can say \(x+3=0\) (or \(y=0\) ) when value of \(x=-3\). Thus, \(x=-3\) which is a root (zero) of equation \(x+3=0\) is actually the value of \(x\) where graph of \(y=f(x)=x+3\) intersects the \(x\)-axis.

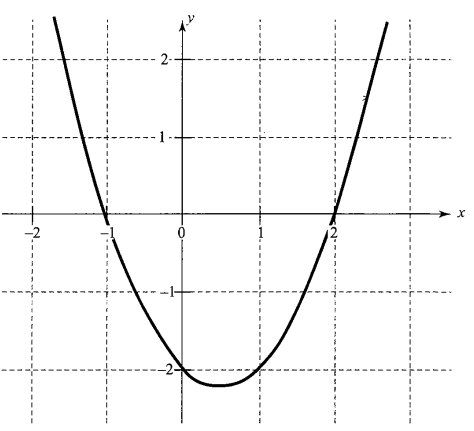

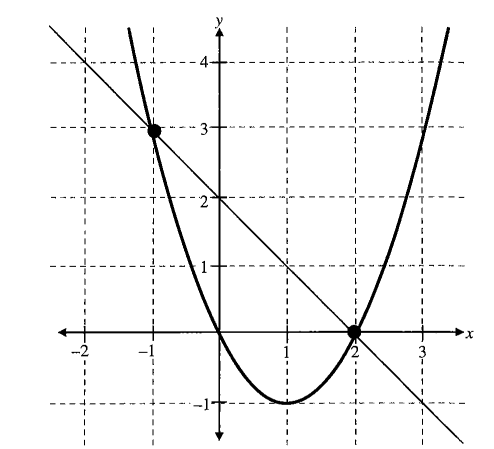

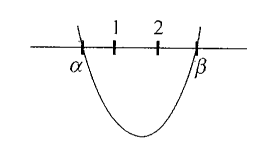

Illustration 2: Consider the function \(f(x)=x^2-x-2\), now for \(f(x)=0\) or \(x^2 -x-2=0\), we have \((x-2)(x+1)=0\) or \(x=-1\) or \(x=2\). Then graph of \(f(x)=x^2-x-2\) cuts the \(x\)-axis at two values of \(x, x=-1\) and \(x=2\).

Following is the graph of \(y=f(x)\).

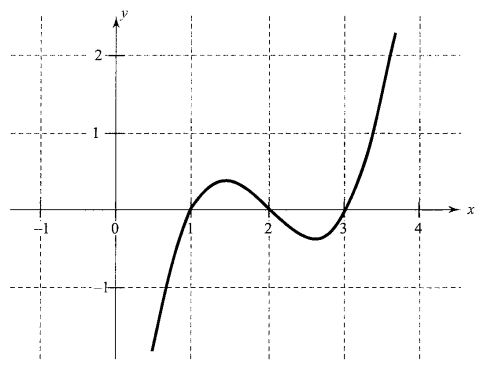

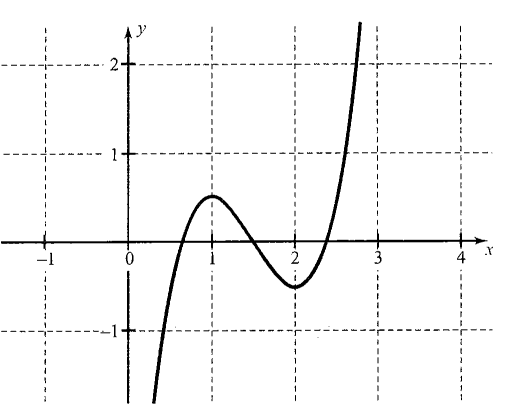

Illustration 3: Consider the function \(f(x)=x^3-6 x^2+11 x-6\), now for \(f(x)=0\) we have \((x-1)(x-2)(x-3)=0\) or \(x=1,2,3\). Then graph of \(y=f(x)\) cuts \(x\)-axis at three values of \(x, x=1,2,3\). Following is the graph of \(y=f(x)\).

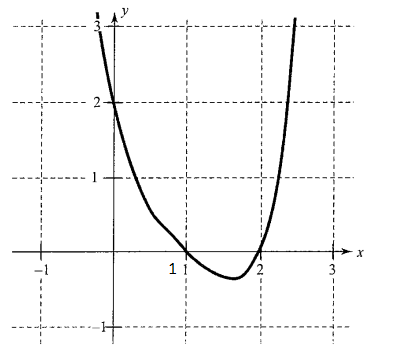

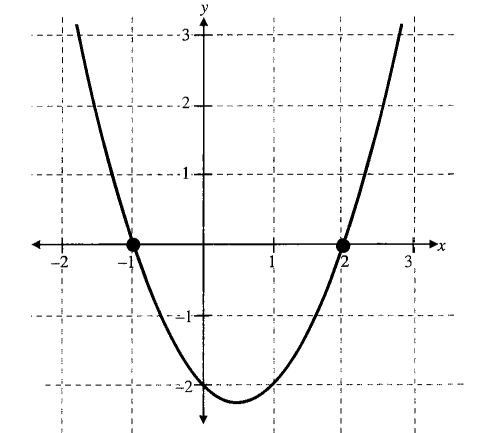

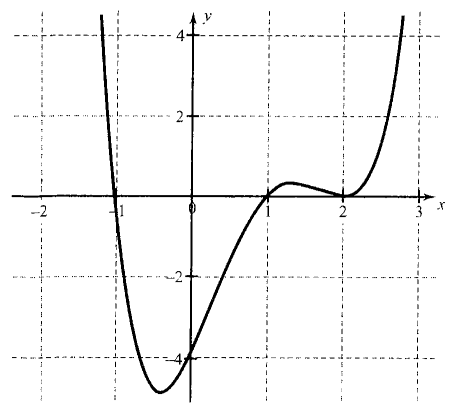

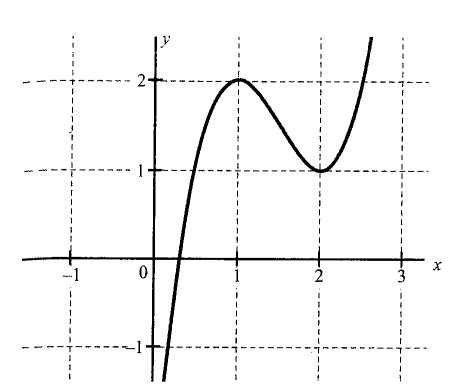

Illustration 4: Consider the function \(f(x)=\left(x^2-3 x+2\right)\left(x^2-x+1\right)\), now for \(f(x)=0\) we have \(x=1\) or \(x=2\), as \(x^2-x+1=0\) is not possible for any real value of \(x\). Hence, \(f(x)=0\) has only two real roots and cuts \(x\)-axis for only two values of \(x, x=1\) and \(x=2\).Following is the graph of \(y=f(x)\).

Thus, roots of equation \(f(x)=0\) are actually those values of \(x\) where graph \(y=f(x)\) meets \(x\)-axis.

Roots (Zeros) of the Equation \(\boldsymbol{f}(\boldsymbol{x})=\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x})\)

Now we know that zeros of the equation \(f(x)=0\) are the \(x\)-coordinates of the points where graph of \(y=f(x)\) intersect the \(x\)-axis, where \(y=0\) or zeros are \(x\)-coordinate of the point of intersection of \(y=f(x)\) and \(y=0\) ( \(x\)-axis)

Consider the equation \(x+5=2\).

Let’s draw the graph of \(y=x+5\) and \(y=2\), which are as shown in the following figure.

Graph of \(y=2\) is a line parallel to \(x\)-axis at height 2 unit above \(x\)-axis. Now in the figure, we can see that graphs of \(y=x+5\) and \(y=2\) intersect at point \((-3,2)\) where value of \(x=-3\).

Also from \(x+5=2\), we have \(x=2-5\) or \(x=-3\), which is a root of the equation \(x+2=5\). Thus root of the equation \(x+5 =2\) occurs at point of intersection of graphs \(y=x+5\) and \(y=2\).

Consider the another example \(x^2-2 x=2-x\). Let’s draw the graph of \(y=x^2-2 x\) and \(y=2-x\) as shown in the following figure.

Now in the figure, we can see that graphs of \(y=x^2-2 x\) and \(y=2-x\) intersect at points \((-1,3)\) and \((2,0)\) or where values of \(x\) are \(x=-1\) and \(x=2\), which are in fact zeros or roots of the equation \(x^2-2 x=2-x\) or \(x^2-x-2=0\).

The given equation simplifies to \(x^2-x-2=0\). So one can also locate the roots of the same equation by plotting the graph of \(y=x^2-x-2\), then the roots of equation are \(x\)-coordinates of points where graph of \(y=x^2-x-2\) intersects with the \(x\)-axis (where \(y=0\) ), as shown in the following figure.

From the above discussion we understand that roots of the equation \(f(x)=\mathrm{g}(x)\) are the \(x\)-coordinate of the points of intersection of graphs \(y=f(x)\) and \(y=g(x)\).

Illustration 1: In how many points graph of \(y=x^3-3 x^2 +5 x-3\) intersect \(x\)-axis?

Solution: Number of point in which \(y=x^3-3 x^2+5 x-3\) intersect the \(x\)-axis is same as number of real roots of the equation \(x^3-3 x^2 +5 x-3=0\).

Now we can see that \(x=1\) satisfies the equation, hence one root of the equation is \(x=1\).

Now dividing \(x^3-3 x^2+5 x-3\) by \(x-1\), we have quotient \(x^2-2 x+3\).

Hence equation reduces to \((x-1)\left(x^2-2 x+3\right)=0\).

Now \(\boldsymbol{x}^2-2 x+3=0\) or \((x-1)^2+2=0\) is not true for any real value of \(\boldsymbol{x}\).

Hence, the only root of the equation is \(x=1\).

Therefore, the graph of \(y=x^3-3 x^2+5 x-3\) cuts the \(x\)-axis in one point only.

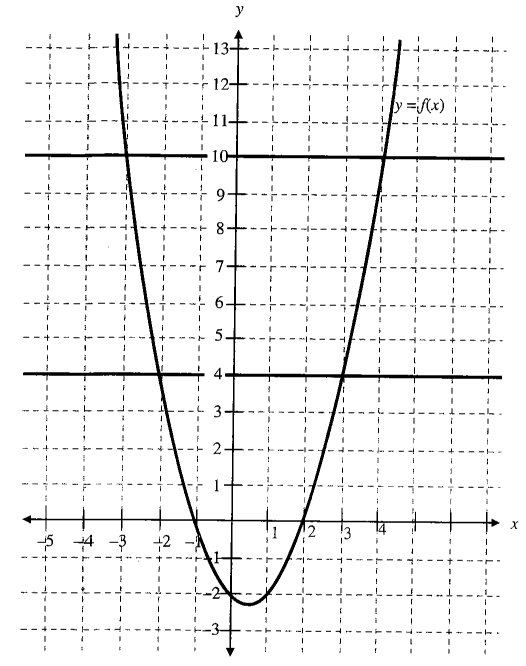

Illustration 2: In the following diagram, the graph of \(y=f(x)\) is given.

Answer the following questions:

(a) what are the roots of the \(f(x)=0\) ?

(b) what are the roots of the \(f(x)=4\) ?

(c) what are the roots of the \(f(x)=10\) ?

Solution:

(a) The root of the equation \(f(x)=0\) occurs for the values of \(x\) where the graphs of \(y=f(x)\) and \(y=0\) intersect.

From the diagram, for these point of intersection \(x=-1\) and \(x=2\). Hence, roots of the equation \(f(x)=0\) are \(x=-1\) and \(x=2\).

(b) The root of the equation \(f(x)=4\) occurs for the values of \(x\) where the graphs of \(y=f(x)\) and \(y=4\) intersect. From the diagram, for these point of intersection \(x=-2\) and \(x=3\). Hence, roots of the equation \(f(x)=0\) are \(x=-2\) and \(x=3\).

(c) Also roots of the equation \(f(x)=10\) are -3 and 4.

Illustration 3: Which of the following pair of graphs intersect?

(i) \(y=x^2-x\) and \(y=1\)

(ii) \(y=x^2-2 x+3\) and \(y=\sin x\)

(iii) \(y=x^2-x+1\) and \(y=x-4\)

Solution: \(y=x^2-x\) and \(y=1\) intersect if \(x^2-x=1 \Rightarrow x^2-x-1=0\), which has real roots.

\(y=x^2-2 x+3\) and \(y=\sin x\) intersect if \(x^2-2 x+3=\sin x\) or \((x-1)^2+2=\sin x\), which is not possible as L.H.S. has the least value 2 , while R.H.S. has the maximum value 1 .

\(y=x^2-x+1\) and \(y=x-4\) intersect if \(x^2-x+1=x-4\) or \(x^2-2 x+5=0\), which has non-real roots. Hence, graphs do not intersect.

Illustration 4: Prove that graphs \(y=2 x-3\) and \(y=x^2 \boldsymbol{-} \boldsymbol{x}\) never intersect.

Solution: \(y=2 x-3\) and \(y=x^2-x\) intersect only when \(x^2-x=2 x-3\) or \(x^2-3 x+3=0\)

Now discriminant \(D=(-3)^2-4(3)=-3<0\)

Hence, roots of the equation are not real, or we can say that there is no real number for which \(2 x-3\) and \(x^2-x\) are equal (or \(y=2 x-3\) and \(y=x^2-x\) intersect).

Hence, proved.

Key Points Solving an Equation

Domain of Equation

It is a set of the values of independent variables \(x\) for which each function used in the equation is defined, i.e., it takes up finite real values. In other words, the final solution obtained while solving any equation must satisfy the domain of the expression of the parent equation.

Illustration 5: Solve \(\frac{x^2-2 x-3}{x+1}=0\).

Solution: Equation \(\frac{x^2-2 x-3}{x+1}=0\) is solvable over \(R-\{-1\}\)

Now \(\quad \frac{x^2-2 x-3}{x+1}=0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad x^2-2 x-3=0 \text { or }(x-3)(x+1)=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x=3(\text { as } x \in R-\{-1\})

\end{aligned}

\)

Illustration 6: Solve \(\left(x^3-4 x\right) \sqrt{x^2-1}=0\).

Solution: Given equation is solvable for \(x^2-1 \geq 0\)

or \(\quad x \in(-\infty,-1][1, \infty)\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(x^3-4 x\right) \sqrt{x^2-1}=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & x(x-2)(x+2) \sqrt{x^2-1}=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & x=0,-2,2,-1,1

\end{aligned}

\)

But \(\quad x \in(-\infty,-1] \cup[1, \infty)\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x= \pm 1, \pm 2

\)

Illustration 7: Solve \(\frac{2 x-3}{x-1}+1=\frac{6 x-x^2-6}{x-1}\).

Solution: \(\frac{2 x-3}{x-1}+1=\frac{6 x-x^2-6}{x-1}, x \neq 1\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{3 x-4}{x-1}=\frac{6 x-x^2-6}{x-1}, x \neq 1 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 3 x-4=6 x-x^2-6, x \neq 1 \\

& \Rightarrow x^2-3 x+2=0, x \neq 1 \\

& \Rightarrow x=2

\end{aligned}

\)

Extraneous Roots

While simplifying the equation, the domain of the equation may expand and give the extraneous roots.

For example, consider the equation \(\sqrt{x}=x-2\).

For solving, we first square it

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { so } \sqrt{x}=x-2 \\

& \Rightarrow x=(x-2)^2 \quad[\text { on squaring both sides }] \\

& \Rightarrow x^2-5 x+4=0 \\

& \Rightarrow(x-1)(x-4)=0 \\

& \Rightarrow x=1,4

\end{aligned}

\)

We observe that \(x=4\) satisfies the given equation but \(x=1\) does not satisfy it.

Hence, \(x=4\) is the only solution of the given equation.

The domain of actual equation is \([2, \infty)\).

While squaring the equation, domain expands to \(R\), which gives extra root \(x=1\).

Loss of Root

Cancellation of common factors from both sides of equation leads to loss of root.

For example, consider an equation \(x^2-2 x=x-2\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad x(x-2)=x-2 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x=1

\end{aligned}

\)

Here we have cancelled factor \(x-2\) which causes the loss of root, \(x=2\)

The correct way of solving is

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2-2 x=x-2 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x^2-3 x+2=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(x-1)(x-2)=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x=1 \text { and } x=2 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Graphs of Polynomial Functions

When the polynomial function is written in standard form, \(f(x) =a_n x^n+a_{n-1} {x}^{n-1}+\cdots+a_1 x+a_0,\left(a_n \neq 0\right)\), the leading term is \(a_n x^n\). In other words, the leading term is the term that the variable has its highest exponent. The degree of a term of a polynomial function is the exponent on the variable. The degree of the polynomial is the largest degree of all of its terms.

For drawing the graph of the polynomial function, we consider the following tests.

Test 1: Leading Co-efficient

If \(n\) is odd and the leading coefficient \(a_n\) is positive, then the graph falls to the left and rises to the right:

If \(n\) is odd and the leading coefficient \(a_n\) is negative, the graph rises to the left and falls to the right.

If \(n\) is even and the leading coefficient \(a_n\) is positive, the graph rises to the left and to the right.

If \(n\) is even and the leading coefficient \(a_n\) is negative, the graph falls to the left and to the right

Test 2: Roots (Zeros) of Polynomial

In other words, when a polynomial function is set equal to zero and has been completely factored and each different factor is written with the highest appropriate exponent, depending on the number of times that factor occurs in the product, the exponent on the factor that the zero is a solution for it gives the multiplicity of that zero.

The exponent indicates how many times that factor would be written out in the product, this gives us a multiplicity.

Multiplicity of Zeros and the \(x\)-Intercept

If \(\boldsymbol{r}\) is a zero of even multiplicity:

This means the graph touches the \(x\)-axis at \(r\) and turns around. This happens because the sign of \(f(x)\) does not change from one side to the other side of \(r\). See the graph of \(f(x)=(x-2)^2(x-1)(x+1)\).

If \(r\) is a zero of odd multiplicity:

This means the graph crosses (also touches if exponent is more than 1) the \(x\)-axis at \(r\). This happens because the sign of \(f(x)\) changes from one side to the other side or \(r\).

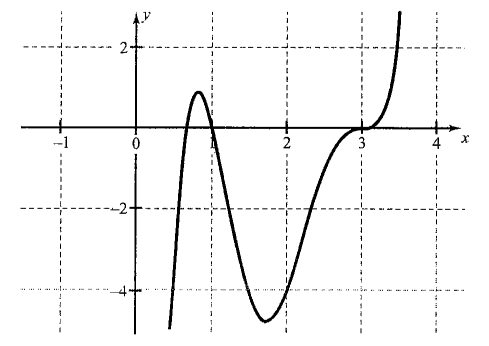

See the graph of \(f(x)=(x-1)(3 x-2)(x-3)^3\)

Thus, in general, polynomial function graphs consist of a smooth line with a series of hills and valleys. The hills and valleys are called turning points. The maximum possible number of turning points is one less than the degree of the polynomial. The point where graph has turning point, derivative of function \(f(x)\) becomes zero, which provides point of local minima or local maxima. Knowledge of derivative provides great help in drawing the graph of the function, hence finding its point of intersection with \(x\)-axis or roots of the equation \(f(x)=0\). Also we know that geometrically the derivative of function at any point of the graph of the function is equal to the slope of tangent at that point to the curve.

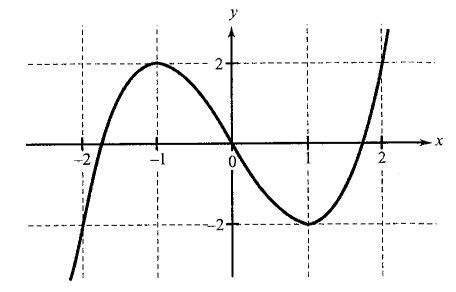

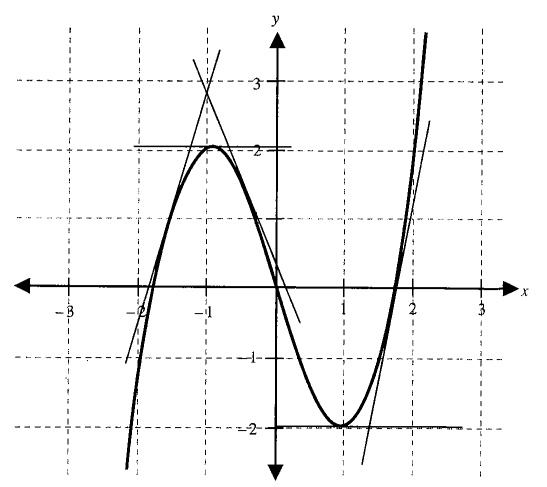

Consider the following graph of the function \(y=f(x)\) as shown in the following figure.

In the figure, we can see that tangent to the curve at point for which \(x<-1\) and \(x>1\) makes acute angle with the positive direction of \(x\)-axis, hence derivative is positive for these points. For \(-\mathbf{1}<x<1\), tangent to the curve makes obtuse angle with the positi ve direction of \(x\)-axis, hence derivative is negative at these points. At \(x=-1\) and \(x=1\), tangent is parallel to \(x\)-axis, where derivative is zero.

Here \(x=-1\) is called point of maxima, where derivative changes sign from positive to negative (from left to right), and \(x=1\) is called point of minima, where derivative changes sign from negative to positive (from left to right).

At point of maxima and minima, derivative of the function is zero.

Illustration 8: Using differentiation method check how many roots of the equation \(x^3-x^2+x-2=0\) are real?

Solution: Let \(y=f(x)=x^3-x^2+x-2\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad \frac{d y}{d x}=3 x^2-2 x+1

\)

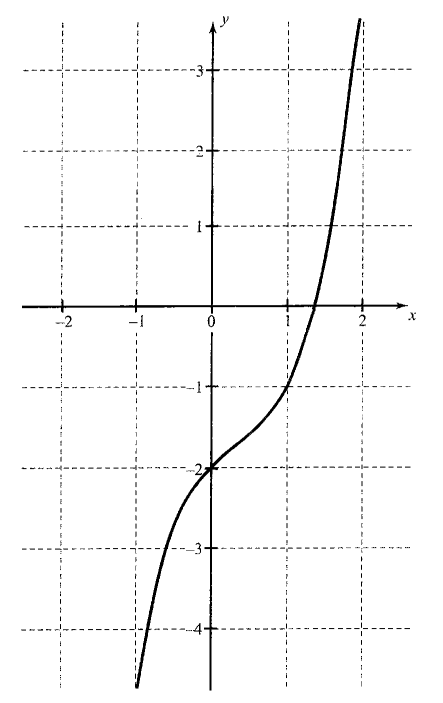

Let \(3 x^2-2 x+1=0\), now this equation has non-real roots, i.e., derivative never becomes zero or graph of \(y=f(x)\) has no turning point.

Also when \(x \rightarrow \infty, f(x) \rightarrow \infty\) and when \(x \rightarrow-\infty, f(x) \rightarrow-\infty\)

Further \(3 x^2-2 x+1>\theta \forall x \in R\)

Thus graph of the function is as shown in the following figure.

Also \(f(0)=-2\); hence graph cuts the \(x\)-axis for some positive value of \(x\).

Hence, the only root of the equation is positive.

Thus we can see that differentiation and then graph of the function is much important in analyzing the equation

Illustration 9: Analyze the roots of the following equations:

(i) \(2 x^3-9 x^2+12 x-(9 / 2)=0\)

(ii) \(2 x^3-9 x^2+12 x-3=0\)

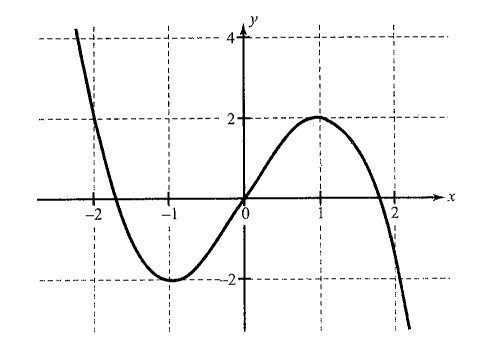

Solution: (i) Let \(f(x)=2 x^3-9 x^2+12 x-(9 / 2)\)

Then \(f^{\prime}(x)=6 x^2-18 x+12=6\left(x^2-3 x+2\right)=6(x-1)(x-2)\)

Now \(f^{\prime}(x)=0 \Rightarrow x=1\) and \(x=2\).

Hence, graph has turn at \(x=1\) and at \(x=2\).

Also \(f(1)=2-9+12-(9 / 2)>0\)

and \(f(2)=16-36+24-(9 / 2)<0\)

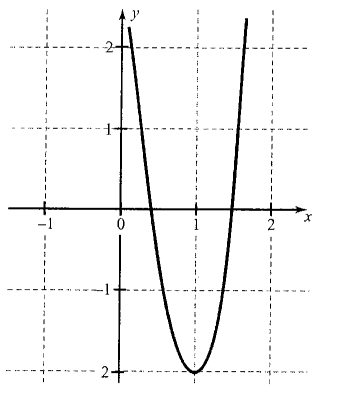

Hence, graph of the function \(y=f(x)\) is as shown in the following figure.

As shown in the figure, graph cuts \(x\)-axis at three distinct point.

Hence, equation \(f(x)=0\) has three distinct roots.

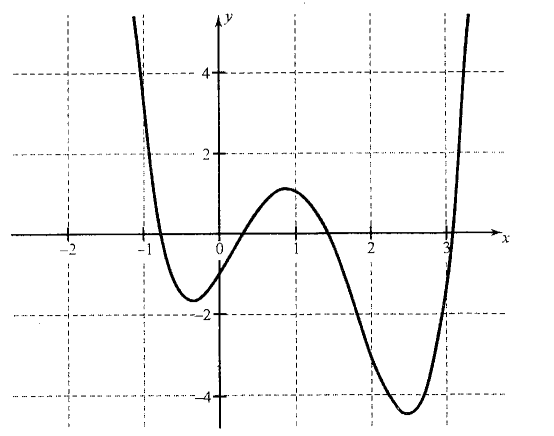

(ii) For \(2 x^3-9 x^2+12 x-3=0, f(x)=2 x^3-9 x^2+12 x-3 f^{\prime}(x)=0 \Rightarrow x=1\) and \(x=2\) Also \(f(1)=2-9+12-3=2\) and \(f(2)=16-36+24-3=1\)

Hence, graph of \(y=f(x)\) is as shown in the following figure.

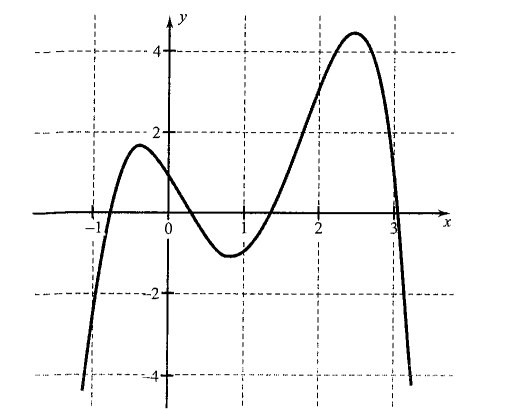

Illustration 10: Find how many roots of the equation \(\boldsymbol{x}^4 +2 x^2-8 x+3=0\) are real.

Solution: Let \(f(x)=x^4+2 x^2-8 x+3\)

\(

\Rightarrow f(x)=4 x^3+4 x-8=4(x-1)\left(x^2+x+2\right)

\)

Now \(f^{\prime}(x)=0 \Rightarrow x=1\)

Hence graph of \(y=f(x)\) has only one turn (maxima/minima).

Now \(f(1)=1+2-8+3<0\)

Also when \(x \rightarrow \pm \infty, f(x) \rightarrow \infty\)

Then graph of the function is as shown in the following figure.

Hence, equation \(f(x)=0\) has only two real roots.

Remainder and Factor Theorem

Remainder Theorem

The remainder theorem states that if a polynomial \(f(x)\) is divided by a linear function \(x-k\), then the remainder is \(f(k)\).

Proof:

In any division,

\(

\text { Dividend }=\text { Divisor } \times \text { Quotient }+ \text { Remainder }

\)

Let \(Q(x)\) be the quotient and \(R\) be the remainder. Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

f(x) & =(x-k) Q(x)+R \\

\Rightarrow \quad f(k) & =(k-k) Q(x)+R=0+R=R

\end{aligned}

\)

Note: If a \(n\)-degree polynomial is divided by a \(m\)-degree polynomial, then the maximum degree of the remainder polynomial is \(m-1\).

Illustration 11: Find the remainder when \(x^3+4 x^2-7 x+\) 6 is divided by \(x-1\).

Solution: Let \(f(x)=x^3+4 x^2-7 x+6\). The remainder when \(f(x)\) is divided by \(x-1\) is

\(

f(1)=1^3+4 \times(1)^2-7+6=4

\)

Illustration 12: If the expression \(a x^4+b x^3-x^2+2 x+3\) has remainder \(4 x+3\) when divided by \(x^2+x-2\), find the value of \(\boldsymbol{a}\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}\).

Solution: Let \(f(x)=a x^4+b x^3-x^2+2 x+3\).

Now, \(x^2+x-2=(x+2) \times(x-1)\).

Given, \(f(-2)=a(-2)^4+b(-2)^3-(-2)^2+2(-2)+3\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =4(-2)+3 \\

\Rightarrow & 16 a-8 b-4-4+3=-5 \\

\Rightarrow & 2 a-b=0 \dots(1)

\end{aligned}

\)

Also,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(1)=a+b-1+2+3=4(1)+3 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & a+b=3 \dots(2)

\end{aligned}

\)

From (1) and (2), \(a=1, b=2\).

Factor Theorem

Factor Theorem Is a Special Case of Remainder Theorem

Let,

\(

\begin{aligned}

f(x) & =(x-k) Q(x)+R \\

\Rightarrow \quad f(x) & =(x-k) Q(x)+f(k)

\end{aligned}

\)

When \(f(k)=0, f(x)=(x-k) Q(x)\). Therefore, \(f(x)\) is exactly divisible by \(x-k\).

Illustration 13: Given that \(x^2+x-6\) is a factor of \(2 x^4 +x^3-a x^2+b x+a+b-1\), find the values of \(a\) and \(b\).

Solution: We have,

\(

x^2+x-6=(x+3)(x-2)

\)

Let,

\(

f(x)=2 x^4+x^3-a x^2+b x+a+b-1

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(-3)=2(-3)^4+(-3)^3-a(-3)^2-3 b+a+b-1=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 134-8 a-2 b=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 4 a+b=67 \dots(1) \\

\Rightarrow & f(2)=2(2)^4+2^3-a(2)^2+2 b+a+b-1=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 39-3 a+3 b=0 \\

\Rightarrow & a-b=13 \dots(2)

\end{aligned}

\)

From (1) and (2), \(a=16, b=3\).

Illustration 14: Use the factor theorem to find the value of \(k\) for which \((a+2 b)\), where \(a, b \neq 0\) is a factor of \(a^4+32 b^4 +a^3 b(k+3)\).

Solution: Let \(f(a)=a^4+32 b^4+a^3 b(k+3)\). Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(-2 b)=(-2 b)^4+32 b^4+(-2 b)^3 b(k+3)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 48 b^4-8 b^4(k+3)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 8 b^4[6-(k+3)]=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 8 b^4(3-k)=0

\end{aligned}

\)

since \(b \neq 0\), so, \(3-k=0\) or \(k=3\).

Illustration 15: If \(c, d\) are the roots of the equation \((x-a)(x-b)-k=0\), prove that \(a, b\) are the roots of the equation \((x-c)(x-d)+k=0\).

Solution: Since \(c\) and \(d\) are the roots of the equation \((x-a)(x-b)-k =0\), therefore,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (x-a)(x-b)-k=(x-c)(x-d) \\

\Rightarrow \quad & (x-a)(x-b)=(x-c)(x-d)+k

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad(x-c)(x-d)+k=(x-a)(x-b)

\)

Clearly, \(a\) and \(b\) are roots of the equation \((x-a)(x-b)=0\). Hence, \(a, b\) are roots of \((x-c)(x-d)+k=0\).

Identity

A relation which is true for every value of the variable is called an identity.

Illustration 16: If \(\left(a^2-1\right) x^2+(a-1) x+a^2-4 a+3=0\) be an identity in \(\boldsymbol{x}\), then find the value of \(\boldsymbol{a}\).

Solution: The given relation is satisfied for all real values of \(x\), so all the coefficients must be zero. Then,

\(

\left.\begin{array}{c}

a^2-1=0 \Rightarrow a= \pm 1 \\

a-1=0 \Rightarrow a=1 \\

a^2-4 a+3=0 \Rightarrow a=1,3

\end{array}\right\} \text { common value of } a \text { is } 1

\)

Illustration 17: Show that \(\frac{(x+b)(x+c)}{(b-a)(c-a)}+\frac{(x+c)(x+a)}{(c-b)(a-b)} +\frac{(x+a)(x+b)}{(a-c)(b-c)}=1\) is an identity.

Solution: Given relation is

\(

\frac{(x+b)(x+c)}{(b-a)(c-a)}+\frac{(x+c)(x+a)}{(c-b)(a-b)}+\frac{(x+a)(x+b)}{(a-c)(b-c)}=1 \dots(1)

\)

When \(x=-a\),

\(

\text { L.H.S. }=\frac{(b-a)(c-a)}{(b-a)(c-a)}=1=\text { R.H.S. }

\)

Similarly, when \(x=-b\),

\(

\text { L.H.S. }=\frac{(c-b)(a-b)}{(c-b)(a-b)}=1=\text { R.H.S. }

\)

When \(x=-c\),

\(

\text { L.H.S. }=\frac{(a-c)(b-c)}{(a-c)(b-c)}=1=\text { R.H.S. }

\)

Thus, the highest power of \(x\) occurring in relation (1) is 2 and this relation is satisfied by three distinct values \(a, b\) and \(c\) of \(x\); therefore, it is an equation but an identity.

Illustration 18: A certain polynomial \(P(x), x \in R\) when divided by \(x-a, x-b\) and \(x-c\) leaves remainders \(a, b\) and \(c\), respectively. Then find the remainder when \(P(x)\) is divided by \((x-a)(x-b)(x-c)\) where \(a, b, c\) are distinct.

Solution: By remainder theorem, \(P(a)=a, P(b)=b\) and \(P(c)=c\).

Let the required remainder be \(R(x)\). Then,

\(

P(x)=(x-a)(x-b)(x-c) Q(x)+R(x)

\)

where \(R(x)\) is a polynomial of degree at most 2. We get \(R(a) =a, R(b)=b\) and \(R(c)=c\). So, the equation \(R(x)-\dot{x}=0\) has three roots \(a, b\) and \(c\). But its degree is at most 2. So, \(R(x)-x\) must be zero polynomial (or identity). Hence \(R(x)=x\).

Quadratic Function

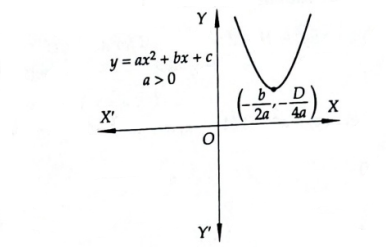

Let \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c\), where \(a, b, c, \in R\) and \(a \neq 0\). We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

f(x) & =a\left[x^2+\frac{b}{a} x+\frac{c}{a}\right] \\

& =a\left[x^2+\frac{b}{a} x+\frac{b^2}{4 a^2}+\frac{c}{a}-\frac{b^2}{4 a^2}\right] \\

& =a\left[\left(x+\frac{b}{2 a}\right)^2+\frac{4 a c-b^2}{4 a^2}\right] \\

& =a\left[\left(x+\frac{b}{2 a}\right)^2-\frac{D}{4 a^2}\right] \\

\Rightarrow \quad\left(y+\frac{D}{4 a}\right) & =a\left(x+\frac{b}{2 a}\right)^2

\end{aligned}

\)

where \(D=b^2-4 a c\) is the discriminant.

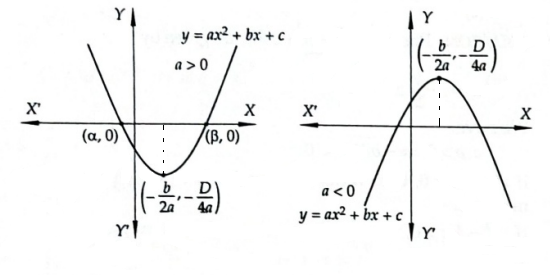

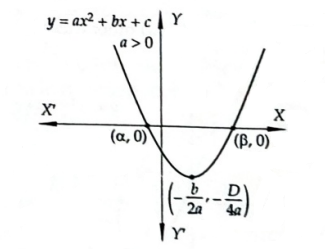

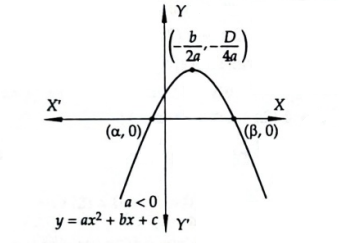

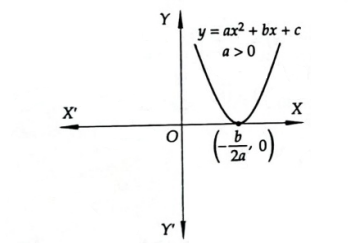

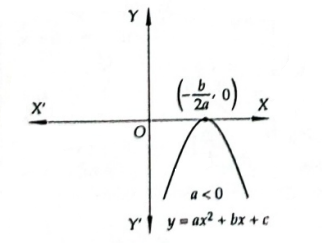

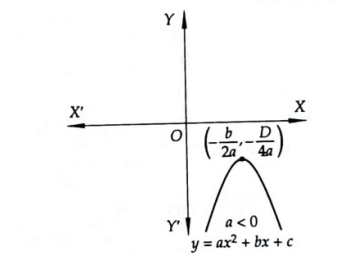

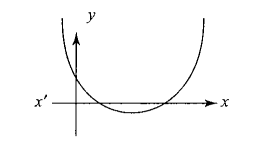

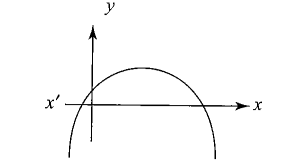

Thus \(y=f(x)\) represents a parabola whose axis is parallel to \(y\)-axis and vertex is \(A(-b / 2 a,-D / 4 a)\). For some values of \(x, f(x)\) may be positive, negative or zero and for \(a>0\), the parabola opens upwards and for \(a<0\), the parabola opens downwards.

Quadratic Expression Graph

Let \(a, b, c\) be real numbers and \(a \neq 0\). Then, \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c\) is known as a quadratic expression or a quadratic polynomial in \(x\). The shape of the curve \(y=f(x)\), is a parabola having vertex at \(\left(-\frac{b}{2 a},-\frac{D}{4 a}\right)\), where \(D=b^2-4 a c\) is the discriminant of the quadratic polynomial.

The roots of the given equation are

\(

\alpha=\frac{-b-\sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a} \text { and } \beta=\frac{-b+\sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}

\)

Since \(\alpha, \beta\) are real and distinct, therefore \(b^2-4 a c>0\).

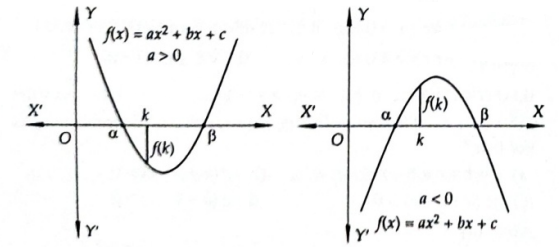

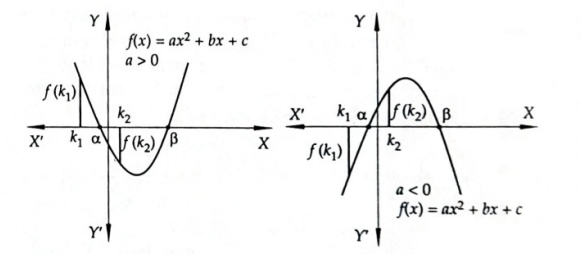

The parabola opens upwards or downwards according as \(a>0\) or \(a<0\) as shown in in Figure below.

We observe the following:

For For \(a>0\) :

The curve \(y=a x^2+b x+c\) is a parabola opening upwards such that:

\(

y_{\min }=-\frac{D}{4 a} \text { at } x=-\frac{b}{2 a} \text { and } y_{\max } \rightarrow \infty

\)

Range of function is \([-D /(4{a})\), \(\infty)\).

\(x=-b /(2 a)\) is a point of minima.

For \(a<0\) :

The curve \(y=a x^2+b x+c\) is a parabola opening downwards such that:

\(

y_{\max }=-\frac{D}{4 a} \text { at } x=-\frac{b}{2 a} \text { and } y_{\min } \rightarrow-\infty

\)

Range of function is \((-\infty,-D / (4a)]\) .

\(x=-b /(2 a)\) is a point of maxima.

Note: The axis of symmetry is defined by \(x=-\frac{b}{2 a}\). If we use the quadratic formula, \(x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}\), to solve \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) for the x -intercepts, or zeros, we find the value of \(x\) halfway between them is always \(x=-\frac{b}{2 a}\), the equation for the axis of symmetry.

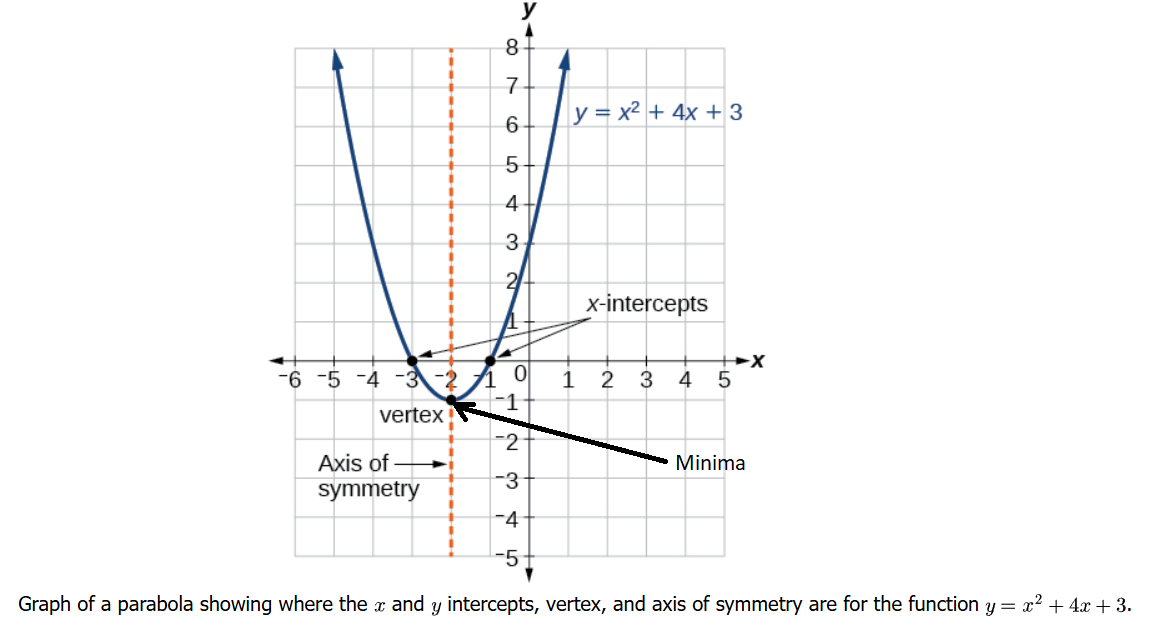

Illustration 1: Figure below represents the graph of the quadratic function written in general form as \(y=x^2+4 x+3\). In this form, \(a=1, b=4\), and \(c=3\). Because \(a>0\), the parabola opens upward. The axis of symmetry is \(x=-\frac{4}{2(1)}=-2\). This also makes sense because we can see from the graph that the vertical line \(x=-2\) divides the graph in half. The vertex always occurs along the axis of symmetry. For a parabola that opens upward, the vertex occurs at the lowest point on the graph, in this instance, \((-2,-1)\). The \(x\)-intercepts, those points where the parabola crosses the \(x\)-axis, occur at \((-3,0)\) and \((-1,0)\). As with the general form, if \(a>0\), the parabola opens upward and the vertex is a minimum.

Note: The standard form of a quadratic function presents the function in the form

\(

f(x)=a(x-h)^2+k

\)

where ( \(h, k\) ) is the vertex. Because the vertex appears in the standard form of the quadratic function, this form is also known as the vertex form of a quadratic function.

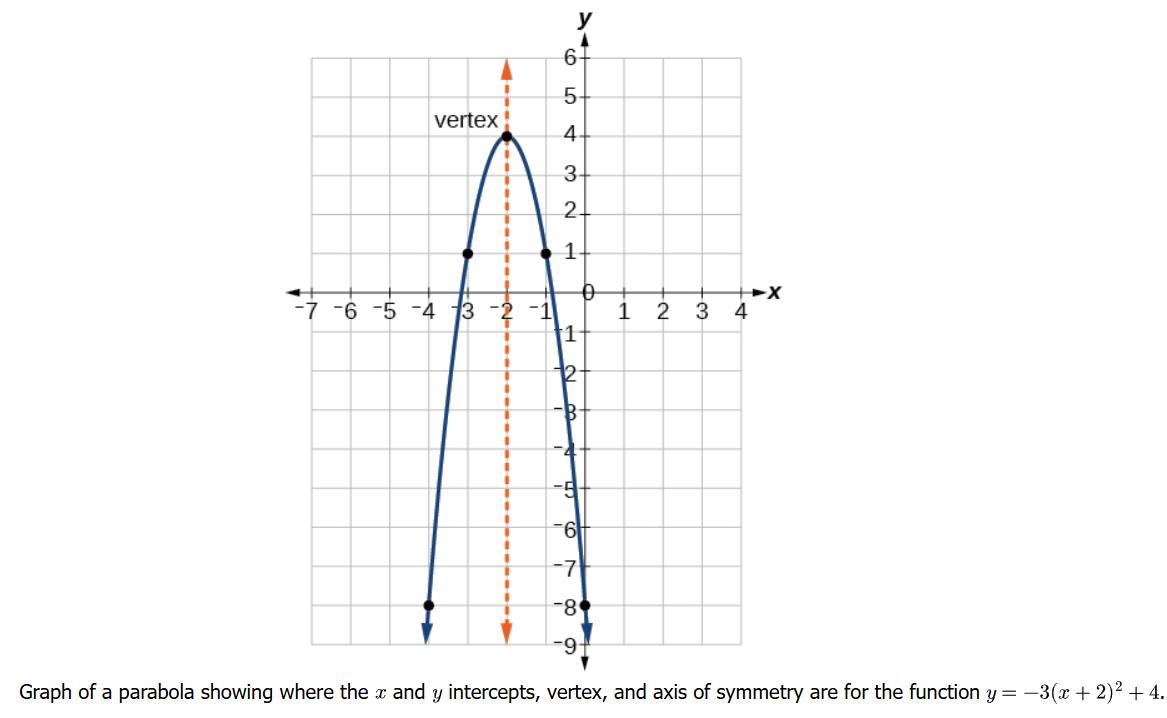

Illustration 2: If \(a<0\), the parabola opens downward, and the vertex is a maximum. Figure below represents the graph of the quadratic function written in standard form as \(y=-3(x+2)^2+4\). Since \(x-h=x+2\) in this example, \(h=-2\). In this form, \(a=-3, h=-2\), and \(k=4\). Because \(a<0\), the parabola opens downward. The vertex is at \((-2,4)\).

Example 1: If \(a\) and \(b(\neq 0)\) are the roots of the equation \(x^2+a x+b=0\), then the least value of \(x^2+a x+b(x \in R)\) is

(a) \(\frac{9}{4}\)

(b) \(-\frac{9}{4}\)

(c) \(-\frac{1}{4}\)

(d) \(\frac{1}{4}\)

Solution: (b) Since \(a\) and \(b\) are the roots of the equation

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& x^2+a x+b=0 \\

\therefore \quad & a+b=-a \text { and } a b=b .

\end{array}

\)

\(

\text { Now, } a b=b \Rightarrow(a-1) b=0 \Rightarrow a=1 [\because b \neq 0]

\)

Putting \(a=1\) in \(a+b=-a\), we get \(b=-2\).

Since \(y=x^2+a x+b\) is a parabola opening upward.

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { So, } y_{\min }=-\frac{D}{4} \quad\left[\text { Using }: y_{\min }=-\frac{D}{4 a} \text { for } y=a x^2+b x+c\right] \\

& \Rightarrow y_{\min }=-\frac{a^2-4 b}{4}=-\frac{9}{4}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 2: The minimum value of \(2 x^2+x-1\), is

(a) \(-\frac{1}{4}\)

(b) \(\frac{3}{4}\)

(c) \(-\frac{9}{8}\)

(d) \(\frac{9}{4}\)

Solution: (c) We know that for \(a>0, y=a x^2+b x+c\) has minimum value equal to \(-\frac{\left(b^2-4 a c\right)}{4 a}\)

Here, \(a=2, b=1\) and \(c=-1\)

So, the minimum value of \(2 x^2+x-1\) is \(-\left(\frac{1+8}{8}\right)=-\frac{9}{8}\)

Now, let \(\alpha\) be a root of the quadratic equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\). Then,

\(

a \alpha^2+b \alpha+c=0 \Rightarrow \text { Point }(\alpha, 0) \text { lies on } y=a x^2+b x+c

\)

It follows from this that every real root of \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) is represented by the point of intersecton of the parabola with \(x\)-axis and vice-versa.

Different Cases of Parabola

Case-I: The parabola will intersect the \(x\)-axis in two distinct points iff \(D>0\).

In this case, the parabola meets \(x\)-axis at ( \(\alpha, 0\) ) and \((\beta, 0)\), where

\(

\alpha=\frac{-b-\sqrt{D}}{2 a} \text { and } \beta=\frac{-b+\sqrt{D}}{2 a}

\)

For \(a>0\), we have

\(

y_{\min }=-\frac{D}{4 a} \text { at } x=-\frac{b}{2 a}, \quad y_{\max } \rightarrow \infty

\)

and, \(\quad y=f(x)\left\{\begin{array}{lll}<0 & \text { for } & \alpha<x<\beta \\ =0 & \text { for } & x=\alpha, \beta \\ >0 & \text { for } & x<\alpha \text { or } x>\beta\end{array}\right.\)

For a \(<0\), we have

\(

y_{\max }=-\frac{D}{4 a} \text { at } x=-\frac{b}{2 a^{\prime}}, y_{\min } \rightarrow-\infty

\)

and, \(y=f(x) \begin{cases}<0 & \text { for } x<\alpha \text { or } x>\beta \\ =0 & \text { for } x=\alpha, \beta \\ >0 & \text { for } \alpha<x<\beta\end{cases}\)

Case-II: The parabola will just touch the \(x\)-axis at one point iff \(D=0\) In this case, the parabola touches \(x\)-axis at ( \(\alpha, 0\) ), where

\(

\alpha=\beta=-\frac{b}{2 a}

\)

For \(a>0\), we have

\(

y_{\min }=-\frac{D}{4 a} \text { at } x=-\frac{b}{2 a}, y_{\max } \rightarrow \infty

\)

For \(a<0\), we have

\(

y=f(x)\left\{\begin{array}{l}

>0 \text { for } x \neq \alpha \\

=0 \text { for } x=\alpha

\end{array}\right.

\)

\(

y_{\max }=0 \text { at } x=-\frac{b}{2 a}, y_{\min } \rightarrow-\infty

\)

and, \(y=f(x)\left\{\begin{array}{l}<0 \text { for } x \neq \alpha \\ =0 \text { for } x=\alpha\end{array}\right.\)

Case-III: The parabola will not interssect \(x\)-axis iff \(D<0\)

In this case, the parabola remains either completely above \(x\)-axis or completely below \(x\)-axis according as \(a>0\) or \(a<0\).

For \(a>0\), we have

\(

y_{\min }=\frac{-D}{4 a} \text { at } x=\frac{-b}{2 a}, \quad y_{\max } \rightarrow \infty

\)

and, \(\quad y=f(x)>0\) for all \(x\)

For a \(<0\), we have

\(

y_{\max }=-\frac{D}{4 a} \text { at } x=-\frac{b}{2 a}, y_{\min } \rightarrow-\infty

\)

and, \(\quad y=f(x)<0\) for all \(x\)

It follows from the above discussion that, for real values of \(x\), the sign of the quadratic expression \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c\) is same as that of ‘ \(a\) ‘, except when the roots of the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) are real and distinct and \(x\) lies between them. It also follows that

\(a x^2+b x+c>0\) for all \(x \in R\) iff \(a>0\) and \(D<0\), and, \(a x^2+b x+c<0\) for all \(x \in R\) iff \(a<0\) and \(D<0\).

Example 3: For all \(x, x^2+2 a x+(10-3 a)>0\), then the interval in which ‘ \(a\) ‘ lies is [IIT (S) 2004]

(a) \(a<-5\)

(b) \(-5<a<2\)

(c) \(a>5\)

(d) \(2<a<5\)

Solution: (b)We have,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& x^2+2 a x+(10-3 a)>0 \text { for all } x \\

\Rightarrow & 4 a^2-4(10-3 a)<0 \\

\Rightarrow & a^2+3 a-10<0 \\

\Rightarrow & (a+5)(a-2)<0 \Rightarrow-5<a<2

\end{array}

\)

Example 4: The integer \(k\) for which the inequality \(x^2-2(4 k-1) x+15 k^2-2 k-7>0\) is valid for any \(x\), is

(a) 2

(b) 3

(c) 4

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) Find the condition for the quadratic inequality

For the quadratic inequality \(a x^2+b x+c>0\) to be true for all real numbers \(x\), two conditions must be met:

The leading coefficient \(a\) must be positive.

The discriminant \(D=b^2-4 a c\) must be negative.

Let \(f(x)=x^2-2(4 k-1) x+15 k^2-2 k-7\). Then, \(f(x)>0\) for all \(x \in R\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad D<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 4(4 k-1)^2-4\left(15 k^2-2 k-7\right)<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad k^2-6 k+8<0 \Rightarrow 2<k<4

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 4: What is the minimum height of any point on the curve \(y=x^2-4 x+6\) above the \(x\)-axis?

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

y & =x^2-4 x+6 \\

& =(x-2)^2+2

\end{aligned}

\)

Now \((x-2)^2 \geq 0\) for all real \(x\).

Then \((x-2)^2+2 \geq 2\) for all real \(x\).

Hence, the minimum value of \(y\) (or \(x^2-4 x+6\) ) is 2 , which is the height of the graph above the \(x\)-axis.

Example 5: What is the maximum height of any point on the curve \(y=-x^2+6 x-5\) above the \(x\)-axis?

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

y & =-x^2+6 x-5 \\

& =4-(x-3)^2

\end{aligned}

\)

Now \((x-3)^2 \geq 0\) for all real \(x\),

Hence, the maximum value of \(y\) (or \(-x^2+6 x-5\) ) is 4 , which is the height of the graph above \(x\)-axis.

Example 6: Find the largest natural number ‘ \(a\) ‘ for which the maximum value of \(f(x)=a-1+2 x-x^2\) is smaller than the minimum value of \(g(x)=x^2-2 a x+10-2 a\).

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

f(x) & =a-1+2 x-x^2 \\

& =a-\left(x^2-2 x+1\right) \\

& =a-(x-1)^2

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the maximum value of \(f(x)\) is ” \(a\) ” when \((x-1)^2=0\) or \(x=1\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

g(x) & =x^2-2 a x+10-2 a \\

& =(x-a)^2+10-2 a-a^2

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the minimum value of \(g(x)\) is \(10-2 a-a^2\) when \((x-a)^2 =0\) or \(x=a\).

Now given that maximum of \(f(x)\) is smaller than the minimum of \(g(x)\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a<-a^2+10-2 a \\

\Rightarrow & a^2+3 a-10<0 \\

\therefore & (a+5)(a-2)<0

\end{aligned}

\)

The largest natural number \(a=1\).

Example 7: Find the least value of \(n\) such that \((n-2) x^2+8 x+n+4>0, \forall x \in R\), where \(n \in N\).

Solution: \((n-2) x^2+8 x+n+4>0, \forall x \in R\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow 64-4(n-2)(n+4)<0 \text { and } n-2>0 \\

& \Rightarrow 16-\left(n^2+2 n-8\right)<0 \text { and } n>2 \\

& \Rightarrow n^2+2 n-24>0 \text { and } n>2 \\

& \Rightarrow(n+6)(n-4)>0 \text { and } n>2 \\

& \Rightarrow n>4 \text { as } n \in N \text { and } n>2 \\

& \Rightarrow n \geq 5

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the least value of \(n\) is 5.

Example 8: If the inequality \(\left(m x^2+3 x+4\right) /\left(x^2+2 x\right. +2)<5\) is satisfied for all \(x \in R\), then find the values of \(m\).

Solution: We have,

\(

x^2+2 x+2=(x+1)^2+1>0, \forall x \in R

\)

Therefore,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{m x^2+3 x+4}{x^2+2 x+2}<5 \\

\Rightarrow & (m-5) x^2-7 x-6<0, \forall x \in R \\

\Rightarrow & m-5<0 \text { and } D<0 \\

\Rightarrow & m<5 \text { and } 49+24(m-5)<0 \\

\Rightarrow & m<\frac{71}{24}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 9: If \(a x^2+b x+6=0\) does not have distinct real roots, then find the least value of \(3 a+b\).

Solution: Given equation \(a x^2+b x+6=0\) does not have distinct real roots. Hence,

\(

\Rightarrow f(x)=a x^2+b x+6 \leq 0, \forall x \in R, \text { if } a<0

\)

\(

f(x)=a x^2+b x+6 \geq 0, \forall x \in R \text {, if } a>0

\)

But

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(0)=6>0 \\

\Rightarrow & f(x)=a x^2+b x+6 \geq 0, \forall x \in R \\

\Rightarrow & f(3)=9 a+3 b+6 \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & 3 a+b \geq-2

\end{aligned}

\)

Therefore, the least value of \(3 a+b\) is -2.

Example 10: Let \(\boldsymbol{a}, \boldsymbol{b}\) and \(\boldsymbol{c}\) be real numbers such that \(a+2 b+c=4\). Find the maximum value of \((a b+b c+c a)\).

Solution: Given,

\(

a+2 b+c=4 \Rightarrow a=4-2 b-c

\)

Let,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a b+b c+c a=x \Rightarrow a(b+c)+b c=x \\

\Rightarrow & (4-2 b-c)(b+c)+b c=x \\

\Rightarrow & 4 b+4 c-2 b^2-2 b c-b c-c^2+b c=x \\

\Rightarrow & 2 b^2-4 b+2 b c-4 c+c^2+x=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 2 b^2+2(c-2) b-4 c+c^2+x=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Since \(b \in R\), so

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 4(c-2)^2-4 \times 2\left(-4 c+c^2+x\right) \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & c^2-4 c+4+8 c-2 c^2-2 x \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & c^2-4 c+2 x-4 \leq 0

\end{aligned}

\)

Since \(c \in R\), so

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 16-4(2 x-4) \geq 0 \Rightarrow x \leq 4 \\

\therefore \quad & \max (a b+b c+a c)=4

\end{aligned}

\)

Position (Location) of Roots of a quadratic Equation

Let \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c\), be a quadratic expression with real coefficients and \(k, k_1, k_2\) be real numbers such that \(k_1<k_2\).

Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the roots of the equation \(f(x)=0\) i.e. \(a x^2+b x+c=0\). Then,

\(

\alpha=\frac{-b-\sqrt{D}}{2 a} \text { and } \beta=\frac{-b+\sqrt{D}}{2 a},

\)

where \(D\) is the discriminant of the equation.

Case-I: When a Number Lies Between the Roots

If a number \(k\) lies between the roots of a quadratic equation \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c=0\), then the equation must have real roots and the sign of \(f(k)\) is opposite to the sign of ‘ \(a\) ‘ as is evident from Figure below.

Thus, a number \(k\) lies between the roots of a quadratic equation \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c=0\), if

(i) \(D>0\)

(ii) af \((k)<0\).

Example 11: The values of a for which the equation \(2 x^2-2(2 a+1) x+a(a+1)=0\) may have one root less than \(a\) and other root greater than \(a\) are given by

(a) \(1>a>0\)

(b) \(-1<a<0\)

(c) \(a \geq 0\)

(d) \(a>0\) or \(a<-1\)

Solution: (d) The given condition suggests that \(a\) lies between the roots. Let \(f(x)=2 x^2-2(2 a+1) x+a(a+1)\). Clearly, coefficient of \(x^2\) is positive. Therefore, ‘ \(a\) ‘ lies between the roots, if Disc \(>0\) and \(f(a)<0\)

Now, Disc \(=4(2 a+1)^2-8 a(a+1)\)

\(\Rightarrow\) Disc \(=8\left(a^2+a+\frac{1}{2}\right)>0\), which is true for all \(a \in R\).

and, \(f(a)<0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 2 a^2-2 a(2 a+1)+a(a+1)<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad-a^2-a<0 \Rightarrow a^2+a>0 \Rightarrow a>0 \text { or } a<-1 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 12: If 6 lies between the roots of the equation \(x^2+2(a-3) x+9=0\), then

(a) \(a \in[-3 / 4, \infty)\)

(b) \(a \in(\infty,-3 / 4)\)

(c) \(a \in(-\infty, 0) \cup(6, \infty)\)

(d) \(a \in(-3 / 4,6)\)

Solution: (b) Let \(f(x)=x^2+2(a-3) x+9\).

If 6 lies between the roots of \(f(x)=0\), then we must have

(i) Disc \(>0\), and

(ii) \(f(6)<0\)

\(\left[\because\right.\) Coeff. of \(x^2\) is positive \(]\)

Now, Disc \(>0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 4(a-3)^2-36>0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(a-3)^2-9>0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a^2-6 a>0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a(a-6)>0 \Rightarrow a<0 \text { or } a>6 \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

and, \(f(6)<0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad 36+12(a-3)+9<0 \Rightarrow a<-\frac{3}{4} \dots(ii)

\)

From (i) and (ii), we get

\(

a<-3 / 4 \text { i.e. } a \in(-\infty,-3 / 4) .

\)

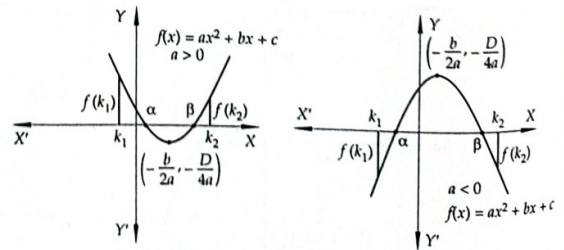

Case-II: When Both Roots Lie Between two Given Numbers

If both the roots \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) of a quadratic equation lie between numbers \(k_1\) and \(k_2\), where \(k_1<k_2\) then one must have

(i) \(D \geq 0\)

(ii) \(a f\left(k_1\right)>0, a f\left(k_2\right)>0\)

(iii) \(k_1<-\frac{b}{2 a}<k_2\)

Example 13: The set of values of \(k\) for which roots of the equation \(x^2-3 x+k=0\) lie in the interval \((0,2)\), is

(a) \((2, \infty)\)

(b) \((0, \infty)\)

(c) \(\left(-\infty, \frac{9}{4}\right)\)

(d) \(\left(2, \frac{9}{4}\right)\)

Solution: (d) Let \(f(x)=x^2-3 x+k\). Clearly, it represents a parabola opening upward. If roots of \(f(x)\) lie in the interval \((0,2)\), then we must have

(i) Discriminate \(\geq 0\)

(ii) \(f(0)>0, f(2)>0\)

(iii) \(x\)-coordinate of the vertex lies between 0 and 2 .

Now,

(i) Discriminant \(\geq 0 \Rightarrow 9-4 k \geq 0 \Rightarrow k \leq \frac{9}{4}\)

(ii) \(f(0)>0\) and \(f(2)>0 \Rightarrow k>0\) and \(k-2>0 \Rightarrow k>2\)

(iii) The \(x\)-coordinate of the vertex is \(\frac{3}{2}\), which lies between 0 and 2.

So, this condition is true for all values of \(k\).

Hence, required set of values of \(k\) is \((2,9 / 4]\)

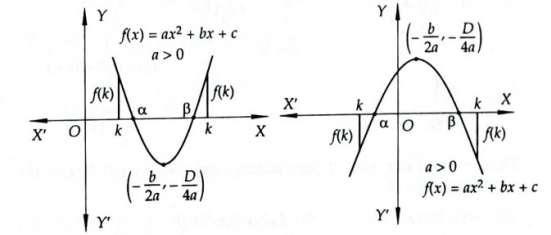

Case-III: When Both Roots Exceed a Given Number

If a number \(k\) is smaller than the roots of a quadratic equation \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c\), then the equation must have real roots and the sign of \(f(k)\) is same as the sign of ‘ \(a\) ‘ as is evident from Figures below. Also, \(k\) is less than the \(x\)-coordinate of the vertex of the parabola \(y=a x^2+b x+c\) i.e. \(k<-b / 2 a\).

Thus, a number \(k\) is smaller than the roots of a quadratic equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\), if

(i) \(D \geq 0\)

(ii) \(a f(k)>0\)

(iii) \(k<-b / 2 a\)

Example 14: If both the roots of the equation \(x^2-6 a x+2-2 a+9 a^2=0\) exceed 3 , then

(a) \(a>\frac{9}{11}\)

(b) \(a \geq \frac{11}{9}\)

(c) \(a>\frac{11}{9}\)

(d) \(a<\frac{11}{9}\)

Solution: (c) Let \(f(x)=x^2-6 a x+2-2 a+9 a^2\). Clearly, coefficient of \(x^2\) is positive. So, \(y=f(x)\) represents a parabola opening upward. Therefore, \(f(x)=0\) will have its both roots greater then 3, if

(i) Disc \(\geq 0\)

(ii) \(x\)-coordinate of vertex \(>3\)

(iii) 3 lies outside the roots of \(f(x)=0\) i.e. \(f(3)>0\)

Now,

(i) Disc \(\geq 0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad 36 a^2-8+8 a-36 a^2 \geq 0 \Rightarrow-8+8 a \geq 0 \Rightarrow a \geq 1 \dots(i)

\)

(ii) \(x\)-coordinate of vertex \(>3\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad 3 a>3 \Rightarrow a>1 \dots(ii)

\)

(iii) \(f(3)>0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 9 a^2-20 a+11>0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(9 a-11)(a-1)>0 \Rightarrow a<1 \text { or } a>\frac{11}{9} \dots(iii)

\end{aligned}

\)

From (i), (ii) and (iii), we get \(a>11 / 9\).

Example 15: If the roots of the equation

\((a+1) x^2-3 a x+4 a=0(a \neq-1)\) greater than unity, then

(a) \(a \in(-\infty,-1) \cup(2, \infty)\)

(b) \(a \in(-16 / 7,-0]\)

(c) \(a \in[-16 / 7,-1)\)

(d) \(a \in(-1 / 2, \infty)\)

Solution: (c) Let \(f(x)=(a+1) x^2-3 a x+4 a\). The equation \(f(x)=0\) will have roots greater than 1 , iff

(i) Discriminant \(\geq 0\)

(ii) \(1<x\)-coordinate of the vertex of the parabola \(y=f(x)\)

(iii) 1 lies outside the roots i.e. \((a+1) f(1)>0\)

Now,

(i) Discriminant \(\geq 0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 9 a^2-16 a(a+1) \geq 0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad-7 a^2-16 a \geq 0 \Rightarrow a(7 a+16) \leq 0 \Rightarrow-\frac{16}{7} \leq a \leq 0 \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) \(1<x\)-coordinate of the vertex

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 1<\frac{3 a}{2(a+1)} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{a-2}{a+1}>0 \Rightarrow a<-1 \text { or } a>2 \dots(ii)

\end{aligned}

\)

and, \((a+1) f(1)>0\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & (a+1)(a+1-3 a+4 a)>0 \\

\Rightarrow & (a+1)(2 a+1)>0 \\

\Rightarrow & a<-1 \text { or } a>-1 / 2 \dots(iii)

\end{array}

\)

From (i), (ii) and (iii), we get

\(

\frac{-16}{7} \leq a<-1 \text { i.e. } a \in[-16 / 7,-1)

\)

Example 16: The set of values of ‘ \(a\) ‘ for which the roots of the equation \((a-3) x^2-2 a x+5 a=0\) are positive, is

(a) \((-\infty, 0) \cup(3, \infty)\)

(b) \([0,15 / 4]\)

(c) \((3,15 / 4)\)

(d) \((3,15 / 4]\)

Solution: (d) Let \(f(x)=(a-3) x^2-2 a x+5 a\). For the roots of \(f(x)=0\) to be positive, we must have

(i) Discriminat \(\geq 0\)

(ii) \(0<x\)-coordinate of vertex of the parabola \(y=f(x)\)

(iii) 0 is outside the roots i.e. \((a-3) f(0)>0\)

Now,

(i) Discriminat \(\geq 0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 4 a^2-20 a(a-3) \geq 0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad-16 a^2+60 a \geq 0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 4 a(4 a-15) \leq 0 \Rightarrow 0 \leq a \leq 15 / 4 \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) \(0<x\)-coordinate of vertex

\(

\Rightarrow \quad \frac{a}{a-3}>0 \Rightarrow a<0 \text { or } a>3 \dots(ii)

\)

and,

(iii) \((a-3) f(0)>0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad(a-3) 5 a>0 \Rightarrow a(a-3)>0 \Rightarrow a<0 \text { or } a>3 \dots(iii)

\)

From (i), (ii) and (iii), we get

\(

3<a \leq 15 / 4 \text { i.e. } a \in(3,15 / 4]

\)

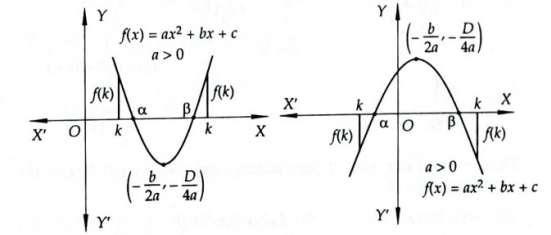

Case-IV: When both the Roots are Less than a Given Number

If a number \(k\) is more than the roots of a quadratic equation \(a x^2+b x+c\), then it is evident from figures below

(i) \(D \geq 0\)

(ii) af \((k)>0\)

(iii) \(k>-b / 2 a\)

Example 17: If the roots of the equation \(x^2-2 a x+a^2+a-3=0\) are real and less than 3, then [IIT 1999]

(a) \(a<2\)

(b) \(2 \leq a \leq 3\)

(c) \(3<a \leq 4\)

(d) \(a>4\)

Solution: (a) Let \(f(x)=x^2-2 a x+a^2+a-3\). Clearly, \(y=f(x)\) represents a parabola opening upward.

If roots of \(f(x)=0\) are less than 3, we must have

(i) Discriminat \(\geq 0\)

(ii) \(x\)-coordinate of vertex of \(y=f(x)\) is less than 3

(iii) 3 lies outside the roots of \(f(x)=0\) i.e. \(f(3)>0\)

Now,

(i) Discriminat \(\geq 0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 4 a^2-4\left(a^2+a-3\right) \geq 0 \Rightarrow-4(a-3) \geq 0 \Rightarrow a-3 \leq 0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a \leq 3 \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) \(x\)-coordinate of vertex \(<3\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad a<3 \dots(ii)

\)

(iii) \(f(3)>0 \Rightarrow a^2-5 a+6>0 \Rightarrow(a-2)(a-3)>0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad a<2 \text { or } a>3 \dots(iii)

\)

From (i), (ii) and (iii), we get \(a<2\).

Example 18: If the equation \(x^2+2(k+1) x+9 k-5=0\) has only negative roots, then

(a) \(k \leq 0\)

(b) \(k \geq 0\)

(c) \(k \geq 6\)

(d) \(k \leq 6\)

Solution: (c) Let \(f(x)=x^2+2(k+1) x+9 k-5\). Clearly, \(y=f(x)\) represents a parabola opening upward. So, the equation \(f(x)=0\) will have both negative roots, if

(i) Discriminant \(\geq 0\)

(ii) \(x\)-coordinate of vertex \(<0\)

(iii) 0 lies outside the roots i.e. \(f(0)>0\)

Now,

(i) Discriminant \(\geq 0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 4(k+1)^2-36 k+20>0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad k^2-7 k+6 \geq 0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(k-1)(k-6) \geq 0 \Rightarrow k \leq 1 \text { or } k \geq 6 \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) \(x\)-coordinate of vertex \(<0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad-(k+1)<0 \Rightarrow k+1>0 \Rightarrow k>-1 \dots(ii)

\)

and (iii) \(f(0)>0 \Rightarrow 9 k-5>0 \Rightarrow k>\frac{5}{9} \dots(iii)\)

From (i), (ii) and (iii), we get \(k \geq 6\).

Case-V: When one Root of a Quadratic Equation Lies in the Interval \(\left(k_1, k_2\right)\), WHERE \(k_1<k_2\).

If exactly one root of the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) lies in the interval ( \(k_1, k_2\) ), then the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) must have real roots and \(f\left(k_1\right), f\left(k_2\right)\) must be of opposite signs as shown below.

Thus, exactly one root of the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) lies in the interval ( \(k_1, k_2\) ) if

(i) \(D>0\)

(ii) \(f\left(k_1\right) f\left(k_2\right)<0\)

Example 19: Find the values of \(\boldsymbol{a}\) for which the equation \(\sin ^4 x+a \sin ^2 x+1=0\) will have a solution.

Solution: Let

\(

t=\sin ^2 x \Rightarrow t \in[0,1]

\)

Hence, \(t^2+a t+1=0\) should have at least one solution in \([0,1]\). Since product of roots is positive and equal to one, \(t^2+a t+1=\) 0 must have exactly one root in \([0,1]\). Hence,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(1)<0 \\

\Rightarrow & 2+a<0 \\

\Rightarrow & a \in(-\infty,-2)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 20: If \(\left(x^2+x+2\right)^2-(a-3)\left(x^2+x+1\right)\left(x^2+x\right. +2)+(a-4)\left(x^2+x+1\right)^2=0\) has at least one root, then find the complete set of values of \(a\).

Solution: Let,

\(

t=x^2+x+1 \Rightarrow t \in\left[\frac{3}{4}, \infty\right)

\)

Hence,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (t+1)^2-(a-3) t(t+1)+(a-4) t^2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & t^2+2 t+1-(a-3)\left(t^2+t\right)+(a-4) t^2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & t(2-a+3)+1=0 \\

\Rightarrow & t=\frac{1}{(a-5)} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{1}{a-5} \geq \frac{3}{4} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{19-3 a}{(a-5)} \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & a \in\left(5, \frac{19}{3}\right]

\end{aligned}

\)

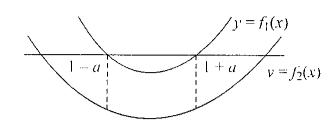

Example 21: For what real values of \(\boldsymbol{a}\) do the roots of the equation \(x^2-2 x-\left(a^2-1\right)=0\) lie between the roots of the equation \(x^2-2(a+1) x+a(a-1)=0\).

Solution: \(x^2-2 x-\left(a^2-1\right)=0 \dots(1)\)

\(

x^2-2(a+1) x+a(a-1)=0 \dots(2)

\)

From Eq. (1),

\(

x=\frac{2 \pm \sqrt{4+4\left(a^2-1\right)}}{2}=1 \pm a

\)

Now, roots of Eq. (1) lie between roots of Eq. (2). Hence, graphs of expressions for Eqs. (1) and (2) are as follows:

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{aligned}

& f_1(x)=x^2-2 x-\left(a^2-1\right) \\

& f_2(x)=x^2-2(a+1) x+a(a-1)

\end{aligned}\\

&\text { From the graph, we have }\\

&\begin{aligned}

& f_2(1-a)<0 \text { and } f_2(1+a)<0 \\

\Rightarrow & (1-a)^2-2(a+1)(1-a)+a(a-1)<0

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad(1-a)[(1-a)-2 a-2-a]<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(1-a)(-4 a-1)<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(a-1)(4 a+1)<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad-\frac{1}{4}<a<1 \dots(3)

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { and }\\

&\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad(1+a)^2-2(a+1)(a+1)+a(a-1)<0 \\

& \Rightarrow-(a+1)^2+a(a-1)<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad-a^2-2 a-1+a^2-a<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 3 a+1>0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a>-\frac{1}{3} \dots(4)

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

From (3) and (4), the required values of a lies in the range \(-1 / 4<a<1\).

Solving Inequalities Using Location of Roots

Example 22: Find the value of \(a\) for which \(a x^2 +(a-3) x+1<0\) for at least one positive real \(x\).

Solution: Let \(f(x)=a x^2+(a-3) x+1\)

Case I: If \(a>0\), then \(f(x)\) will be negative only for those values of \(x\) which lie between the roots. From the graphs, we can see that \(f(x)\) will be less than zero for at least one positive real \(x\), when \(f(x)=0\) has distinct roots and at least one of these roots is a positive real root.

Since \(f(0)=1>0\), the favourable graph according to the question is shown in the figure given above. From the graph, we can see that both the roots are non-negative. For this,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { (i) } D>0 \Rightarrow(a-3)^2-4 a>0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a<1 \text { or } a>9 \dots(1)

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) sum \(>0\) and product \(\geq 0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad-(a-3)>0 \text { and } 1 / a>0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 0<a<3 \dots(2)

\end{aligned}

\)

From (1) and (2), we have

\(

a \in(0,1)

\)

Case II: \({a}<0\)

Since \(f(0)=1>0\), then graph is as shown in the figure, which shows that \(a x^2+(a-3) x+1<0\), for at least one positive \(x\).

Case III: \(a=0\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { If } a=0 \\

& \qquad f(x)=-3 x+1 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad f(x)<0, \forall x>1 / 3

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus, from all the cases, the required set of values of \(a\) is \((-\infty, 1)\).

Example 23: If \(x^2+2 a x+a<0 \forall x \in[1,2]\), then find the values of \(\boldsymbol{a}\).

Solution: Given,

\(

x^2+2 a x+a<0, \forall x \in[1,2]

\)

Hence, 1 and 2 lie between the roots of the equation \(x^2+2 a x +a=0\),

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad f(1)<0 \text { and } f(2)<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 1+2 a+a<0,4+4 a+a<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a<-\frac{1}{3}, a<-\frac{4}{5} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a \in\left(-\infty,-\frac{4}{5}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 24: If \(\left(y^2-5 y+3\right)\left(x^2+x+1\right)<2 x\) for all \(x \in R\), then find the interval in which \(y\) lies.

Solution: \(\left(y^2-5 y+3\right)\left(x^2+x+1\right)<2 x, \forall x \in R\)

\(

\Rightarrow y^2-5 y+3<\frac{2 x}{x^2+x+1} \quad\left(\because \quad x^2+x+1>0 \forall x \in R\right)

\)

L.H.S. must be less than the least value of R.H.S. Now lets find the range of R.H.S.

Let

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{2 x}{x^2+x+1}=p \\

\Rightarrow \quad & p x^2+(p-2) x+p=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Since \(x\) is real,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (p-2)^2-4 p^2 \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & -2 \leq p \leq \frac{2}{3}

\end{aligned}

\)

The minimum value of \(2 x /\left(x^2+x+1\right)\) is -2. So,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& y^2-5 y+3<-2 \\

\Rightarrow & y^2-5 y+5<0 \\

\Rightarrow & y \in\left(\frac{5-\sqrt{5}}{2}, \frac{5+\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 25: Find the values of \(\boldsymbol{a}\) for which \(\mathbf{4}^{\boldsymbol{t}}-(\boldsymbol{a} -4) 2^t+(9 / 4) a<0, \forall t \in(1,2)\).

Solution: Let \(2^{t}=x\) and \(f(x)=x^2-(a-4) x+(9 / 4) a\). We want \(f(x)< 0, \forall x \in\left(2^1, 2^2\right)\), i.e., \(\forall x \in(2,4)\).

(i) Since coefficient of \(x^2\) in \(f(x)\) is positive, \(f(x)<0\) for some \(x\) only when roots of \(f(x)=0\) are real and distinct. So,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& D>0 \\

\Rightarrow & a^2-17 a+16>0

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) Since we want \(f(x)<0 \forall x \in(2,4)\), one of the roots of \(f(x) =0\) should be smaller than 2 and the other must be greater than 4, i.e.,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(2)<0 \text { and } f(4)<0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & a<-48 \text { and } a>128 / 7

\end{aligned}

\)

which is not possible. Hence, no such \(a\) exists.

Algebraic Interpretation of Rolle’s Theorem

Let \(f(x)\) be a polynomial having \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) as its roots such that \(\alpha<\beta\). Then, \(f(\alpha)=f(\beta)=0\). Also, a polynomial function is everywhere continuous and differentiable. Thus, \(f(x)\) satisfies all the three conditions of Rolle’s Theorem. Consequently, there exists \(\gamma \in(\alpha, \beta)\) such that \(f^{\prime}(\gamma)=0\) i.e. \(f^{\prime}(x)=0\) at \(x=\gamma\).

In other words \(x=\gamma\) is a root of \(f^{\prime}(x)=0\).

Thus, algebraically Rolle’s Theorem can be interpreted as follows:

Between any two roots of a polynomial \(f(x)\), there is always a root of its derivative \(f^{\prime}(x)\).

Example 26: Let \(a, b, c\) be non-zero real numbers, such that

\(

\int_0^1\left(1+\cos ^8 x\right)\left(a x^2+b x+c\right) d x=\int_0^2\left(1+\cos ^8 x\right)\left(a x^2+b x+c\right) d x

\)

then the quadratic equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) has

(a) no root in \((0,2)\)

(b) at least one root in \((1,2)\)

(c) two roots in \((0,2)\)

(d) two imaginary roots

Solution: (b) Consider the function

\(

\phi(x)=\int_0^x\left(1+\cos ^8 x\right)\left(a x^2+b x+c\right) d x

\)

Clearly, \(\phi(x)\) being an integral function, is continuous and differentiable on \([1,2]\) and \((1,2)\) respectively such that \(\phi(1)=\phi(2)\) (given). Therefore, by Rolle’s Theorem there exists at least one point \(k \in(1,2)\) such that \(\phi^{\prime}(k)=0\).

We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \phi^{\prime}(x)=\left(1+\cos ^8 x\right)\left(a x^2+b x+c\right) \\

\therefore & \phi^{\prime}(k)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & \left(1+\cos ^8 k\right)\left(a k^2+b k+c\right)=0 . \\

\Rightarrow & a k^2+b k+c=0 \\

\Rightarrow & k \text { is a root of } a x^2+b x+c=0 .

\end{aligned} \quad\left[1+\cos ^8 k \neq 0\right]

\)

Also, \(k \in(1,2)\).

Example 27: If \(a+b+c=0\) then the quadratic equation \(3 a x^2+2 b x+c=0\) has

(a) at least one root in \((0,1)\)

(b) one root in \((2,3)\) and the other in \((-2,-1)\)

(c) imaginary roots

(d) none of these

Solution: (a) Consider the function \(\phi(x)=a x^3+b x^2+c x\).

Obviously \(\phi(x)\), being a polynomial, is every where continuous and differentiable

Also, \(\quad \phi(0)=0, \quad \phi(1)=a+b+c=0\) [Given]

Therefore, by Rolle’s Theorem there exists a point \(\lambda \in(0,1)\) such that \(\quad \phi^{\prime}(\lambda)=0\).

We have,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& \phi^{\prime}(x)=3 a x^2+2 b x+c \\

\therefore & \phi^{\prime}(\lambda)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 3 a \lambda^2+2 b \lambda+c=0 \\

\Rightarrow & \lambda \text { is a root of } 3 a x^2+2 b x+c=0

\end{array}

\)

Thus, \(3 a x^2+2 b x+c=0\) has a root in \((0,1)\).