5.7 Entrance Corner (Quadratic Expressions and equations)

Some Definitions

Real Polynomial:

Let \(a_0, a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n\) be real numbers and \(x\) is a real variable. Then, \(f(x)=a_0+a_1 x+a_2 x^2+\cdots+a_n x^n\) is called a real polynomial of real variable \(x\) with real coefficients.

Complex Polynomial:

If \(a_0, a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n\) are complex numbers and \(x\) is a varying complex number, then \(f(x)=a_0+a_1 x+a_2 x^2+\cdots+a_n x^n\) is called a complex polynomial or a polynomial of complex coefficients.

Rational Expression or Rational Function:

An expression of the form

\(

\frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}

\)

where \(P(x)\) and \(Q(x)\) are polynomials in \(x\) is called a rational expression.

In the particular case when \(Q(x)\) is a non-zero constant,

\(

\frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}

\)

reduces to a polynomial. Thus every polynomial is a rational expression but the converse is not true. Some of the examples are as follows:

(1) \(\frac{x^2-5 x+4}{x-2}\)

(2) \(x^2-5 x+4\)

(3) \(\frac{1}{x-2}\)

(4) \(x+\frac{1}{x}\), i.e., \(\frac{x^2+1}{x}\).

Degree of a Polynomial:

A polynomial \(f(x)=a_0+a_1 x+a_2 x^2+\cdots+a_n x^n\), real or complex, is a polynomial of degree \(n\), if \(a_n \neq 0\).

The polynomials \(2 x^3-7 x^2+x+5\) and \((3-2 i) x^2-i x+5\) are polynomials of degree 3 and 2, respectively

A polynomial of second degree is generally called a quadratic polynomial, and polynomials of degree 3 and 4 are known as cubic and bi-quadratic polynomials, respectively.

Polynomial Equation:

If \(f(x)\) is a polynomial, then \(f(x)=0\) is called a polynomial equation.

If \(f(x)\) is a quadratic polynomial, then \(f(x)=0\) is called a quadratic equation. The general form of a quadratic equation is \(a x^2 +b x+c=0, a \neq 0\). Here, \(x\) is the variable and \(a, b\) and \(c\) are called coefficients, real or imaginary.

Roots of an Equation:

The values of the variable satisfying a given equation are called its roots.

Thus, \(x=\alpha\) is a root of the equation \(f(x)=0\), if \(f(\alpha)=0\).

For example, \(x=1\) is a root of the equation \(x^3-6 x^2+11 x-6=0\), because \(1^3-6 \times 1^2+11 \times 1-6=0\).

Similarly, \(x=\omega\) and \(x=\omega^2\) are roots of the equation \(x^2+x+1=0\) as they satisfy it (where \(\omega\) is the complex cube root of unity).

Solution Set:

The set of all roots of an equation, in a given domain, is called the solution set of the equation.

For example, the set \(\{1,2,3\}\) is the solution set of the equation \(x^3-6 x^2+11 x-6=0\).

Solving an equation means finding its solution set. In other words, solving an equation is the process of obtaining all its roots.

Illustration 1: If \(x=1\) and \(x=2\) are solutions of the equation \(x^3+a x^2+b x+c=0\) and \(a+b=1\), then find the value of \(\boldsymbol{b}\).

Solution: Since \(x=1\) is a root of the given equation it satisfies the equation.

Hence, putting \(x=1\) in the given equation, we get

\(

a+b+c=-1

\)

but given that

\(

a+b=1

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\Rightarrow \quad c=-2\\

&\text { Now put } x=2 \text { in the given equation, we have }\\

&\begin{aligned}

& 8+4 a+2 b-2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 6+2 a+2(a+b)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 6+2 a+2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & a=-4 \\

\Rightarrow & b=5

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Illustration 2: Let \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c\), where \(a, b, c \in R\) and \(a \neq 0\). It is known that \(f(5)=-3 f(2)\) and that 3 is a root of \(f(x)=0\), then find the other root of \(f(x)=0\).

Solution: \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c\)

Given that \(f(5)=-3 f(2)\)

\(

25 a+5 b+c=-3(4 a+2 b+c)

\)

\(

37 a+11 b+4 c=0 \dots(1)

\)

Also \(x=3\) satisfies \(f(x)=0\)

\(

\therefore \quad 9 a+3 b+c=0 \dots(2)

\)

or \(\quad 36 a+12 b+4 c=0 \dots(3)\)

[Multiplying Eq. (2) by 4]

Subtracting (3) from (1), we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a-b=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & a=b \quad \Rightarrow \operatorname{In}(2) \text { put } b=a, \\

\Rightarrow \quad & 12 a+c=0 \text { or } c=-12 a

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, equation \(f(x)=0\) becomes

\(

a x^2+a x-12 a=0

\)

\(

x^2+x-12=0

\)

\(

(x-3)(x+4)=0 \quad \text { or } \quad x=-4,3

\)

Illustration 3: A polynomial in \(\boldsymbol{x}\) of degree three vanishes when \(x=1\) and \(x=-2\), and has the values 4 and 28 when \(x=-1\) and \(x=2\), respectively. Then find the value of polynomial when \(\boldsymbol{x}=\mathbf{0}\).

Solution: From the given data \(f(x)=(x-1)(x+2)(a x+b)\)

Now \(f(-1)=4\) and \(f(2)=28\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad(-1-1)(-1+2)(-a+b)=4

\)

and \(\quad(2-1)(2+2)(2 a+b)=28\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad a-b=2 \text { and } 2 a+b=7

\)

Solving, \(a=3\) and \(b=1\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & f(x)=(x-1)(x+2)(3 x+1) \\

\Rightarrow & f(0)=-2

\end{array}

\)

Illustration 4: If \((1-p)\) is a root of quadratic equation \(x^2+p x+(1-p)=0\), then find its roots.

Solution: Since \((1-p)\) is the root of quadratic equation

\(

x^2+p x+(1-p)=0 \dots(1)

\)

So \((1-p)\) satisfies the above equation

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & (1-p)^2+p(1-p)+(1-p)=0 \\

\therefore & (1-p)[1-p+p+1]=0 \\

\therefore & (1-p)(2)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & p=1

\end{array}

\)

On putting this value of \(p\) in Eq. (1), we get

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& x^2+x=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & x(x+1)=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & x=0,-1

\end{array}

\)

Illustration 5: The quadratic polynomial \(p(x)\) has the following properties:

\(\boldsymbol{p}(\boldsymbol{x})\) can be positive or zero for all real numbers

\(

p(1)=0 \text { and } p(2)=2 .

\)

Then find the quadratic polynomial.

Solution: \(p(x)\) is positive or zero for all real numbers also \(\quad \boldsymbol{p}(1)=0\)

then we have \(p(x)=k(x-1)^2\), where \(k>0\)

Now \(\quad p(2)=2\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & k=2 \\

\therefore & p(x)=2(x-1)^2

\end{array}

\)

Roots of Quadratic Equation with Real Coefficients

An equation of the form

\(

a x^2+b x+c=0 \dots(i)

\)

where \(a \neq 0, a, b, c \in R\) is called a quadratic equation with real coefficients.

The quantity \(D=b^2-4 a c\) is known as the discriminant of the quadratic equation in (i) whose roots are given by

\(

\alpha=\frac{-b+\sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a} \text { and } \beta=\frac{-b-\sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}

\)

Proof: Proof: Step-by-step derivation

Start with the standard quadratic equation:

\(

a x^2+b x+c=0

\)

Divide by \(a\) :

Divide all terms by the coefficient of \(x^2\), which is \(a\), to get a leading coefficient of 1.

\(

x^2+\frac{b}{a} x+\frac{c}{a}=0

\)

Move the constant term:

Subtract \(\frac{c}{a}\) from both sides of the equation to move the constant term to the right side. \(x^2+\frac{b}{a} x=-\frac{c}{a}\)

Complete the square:

Take half of the coefficient of the \(x \operatorname{term}\left(\frac{b}{a}\right)\), which is \(\frac{b}{2 a}\). Square this value \(\left(\frac{b}{2 a}\right)^2=\frac{b^2}{4 a^2}\), and add it to both sides of the equation. \(x^2+\frac{b}{a} x+\frac{b^2}{4 a^2}=-\frac{c}{a}+\frac{b^2}{4 a^2}\)

Factor the left side:

The left side can now be factored as a perfect square trinomial: \(\left(x+\frac{b}{2 a}\right)^2\).

\(

\left(x+\frac{b}{2 a}\right)^2=-\frac{c}{a}+\frac{b^2}{4 a^2}

\)

Simplify the right side:

To combine the terms on the right side, find a common denominator ( \(4 a^2\) ) and simplify.

\(

\left(x+\frac{b}{2 a}\right)^2=\frac{b^2-4 a c}{4 a^2}

\)

Take the square root:

Take the square root of both sides. Remember to include the \(\pm\) sign on the right side because there are two possible roots. \(x+\frac{b}{2 a}= \pm \sqrt{\frac{b^2-4 a c}{4 a^2}}\)

Isolate \(x\) :

Simplify the square root on the right side and then subtract \(\frac{b}{2 a}\) from both sides to solve for \(x\).

\(x=-\frac{b}{2 a} \pm \frac{\sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}\)

Combine the terms to get the standard quadratic formula. \(x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}\)

The nature of the roots is as given below :

Case-I: The roots are real and distinct iff \(D>0\):

Illustration: Consider the quadratic equation:

\(

x^2-3 x+2=0

\)

Here, the coefficients are \(a=1, b=-3\), and \(c=2\).

Calculate the discriminant (\(D\)):

\(

\begin{gathered}

D=b^2-4 a c \\

D=(-3)^2-4(1)(2) \\

D=9-8 \\

D=1

\end{gathered}

\)

Check the condition:

Since \(\boldsymbol{D}=1>0\), the condition is met, and we expect two real and distinct roots.

Case-II: The roots are real and equal iff \(D=0\):

Illustration: \(x^2+4 x+4=0\)

\(a=1, b=4, c=4\)

\(D=(4)^2-4(1)(4)=16-16=0\)

Roots: \(x=\frac{-4}{2 \cdot 1}=-2\). The roots are -2 and -2.

Case-III: The roots are complex with non-zero imaginary part iff \(D<0\)

For a quadratic equation of the form \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) with real coefficients \(a, b\), and \(c\), the roots are complex with a non-zero imaginary part if and only if its discriminant, \(\boldsymbol{D}\), is less than zero ( \(\boldsymbol{D}<0\) ).

The discriminant is calculated using the formula:

\(

D=b^2-4 a c

\)

The roots of the equation are given by the quadratic formula:

\(

x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{D}}{2 a}=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}

\)

If \(\boldsymbol{D}<0\), the expression under the square root is negative, resulting in an imaginary number. The roots will then be a pair of complex conjugates of the form \(\boldsymbol{p} \boldsymbol{\pm} \boldsymbol{q} \boldsymbol{i}\), where \(\boldsymbol{q}\) is the non-zero imaginary part.

Illustration: Here are some examples of quadratic equations where \(\boldsymbol{D}<0\), leading to complex roots with non-zero imaginary parts:

\(

x^2+4 x+5=0, \quad \text { Discriminant }\left(\mathrm{D}=b^2-4 a c\right)=4^2-4(1)(5)=16-20=-4

\)

Case-IV: The roots are rational iff \(a, b, c\) are rational and \(D\) is a perfect square.

Illustration: Rational roots

The equation \(x^2-5 x+6=0\) has \(a=1, b=-5, c=6\).

The coefficients \(a, b, c\) are all rational.

The discriminant is \(\boldsymbol{D}=(-5)^2-4(1)(6)=25-24=1\).

\(\boldsymbol{D}=1\) is a perfect square \(\left(1^2=1\right)\).

The roots are \(x=\frac{-(-5) \pm \sqrt{1}}{2(1)}=\frac{5 \pm 1}{2}\), which are \(x=3\) and \(x=2\). Both are rational.

Case-V: The roots are of the form \(p+\sqrt{q}(p, q \in Q)\) iff \(a, b, c\) are rational and \(D\) is not a perfect square.

The statement describes the conditions under which a quadratic equation with rational coefficients will have irrational roots of the form \(p+\sqrt{q}\), which always appear as conjugate pairs \(p \pm \sqrt{q}\). These conditions are met when the discriminant, \(D=b^2-4 a c\), is a positive rational number but not a perfect square of a rational number.

Illustration: Consider the quadratic equation \(\boldsymbol{x}^2-{4 x}-\mathbf{1}=\mathbf{0}\).

The coefficients are \(a=1, b=-4\), and \(c=-1\), which are all rational.

The discriminant is \(\boldsymbol{D}=\boldsymbol{b}^2-4 a c=(-4)^2-4(1)(-1)=16+4=20\).

Since 20 is not a perfect square, the roots will be irrational.

Using the quadratic formula, the roots are:

\(

x=\frac{-(-4) \pm \sqrt{20}}{2(1)}=\frac{4 \pm 2 \sqrt{5}}{2}=2 \pm \sqrt{5} .

\)

These roots, \(2+\sqrt{5}\) and \(2-\sqrt{5}\), are in the form \(p \pm \sqrt{q}\) with \(p=2\) and \(q=5\)

Case VI: If \(a=1, b, c \in I\) and the roots are rational numbers, then these roots must be integers.

Illustration: The quadratic equation \(x^2-5 x+6=0\) has coefficients \(a=1, b=-5\), and \(c=6\).

The roots are calculated as:

\(

x=\frac{5 \pm \sqrt{(-5)^2-4(1)(6)}}{2}=\frac{5 \pm \sqrt{25-24}}{2}=\frac{5 \pm 1}{2}

\)

The roots are \(x_1=\frac{5+1}{2}=3\) and \(x_2=\frac{5-1}{2}=2\), which are both integers.

Case-VII: If a quadratic equation in \(x\) has more than two roots, then it is an identity in \(x\) that is \(a=b=c=0\).

The fundamental theorem of algebra states that a polynomial of degree \(n\) has at most \(n\) roots. A quadratic equation is a polynomial of degree 2. Thus, a quadratic equation can have at most two roots.

The only way for the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) to have more than two roots is if it is an identity, meaning it holds true for every value of \(x\). For this to be the case, the coefficients of each power of \(x\) must be zero.

Therefore, if \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) has more than two roots, then \(a=0, b=0\), and \(c=0\)

Illustration: Consider the equation:

\(

2 x^2-2 x^2+3 x-3 x+5-5=0

\)

This equation simplifies to \(0 x^2+0 x+0=0\).

This is an identity because it is true for every value of \(x\). For example, if \(x=1\), we get \(0=0\). If \(x=100\), we get \(0=0\). This equation has an infinite number of roots, and its coefficients are all zero.

Example 1: If the roots of the equation \(x^2-8 x+a^2 -6 a=0\) are real distinct, then find all possible values of \(a\).

Solution: Since the roots of the given equation are real and distinct, we must have

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& D>0 \\

\Rightarrow & 64-4\left(a^2-6 a\right)>0 \\

\Rightarrow & 4\left[16-a^2+6 a\right]>0 \\

\Rightarrow & -4\left(a^2-6 a-16\right)>0 \\

\Rightarrow & a^2-6 a-16<0 \\

\Rightarrow & (a-8)(a+2)<0 \\

\Rightarrow & -2<a<8

\end{array}

\)

Hence, the roots of the given equation are real if \(a\) lies between -2 and 8.

Example 2: If the equation \((3 x)^2+\left(27 \times 3^{1 / p}-15\right) x+4=0\) has equal roots, then \(p=\)

(a) 0

(b) 2

(c) \(-1 / 2\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) The given equation will have equal roots iff

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& \text { D }=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \left(27 \times 3^{1 / p}-15\right)^2-144=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & 27 \times 3^{1 / p}-15= \pm 12 \Rightarrow 27 \times 3^{1 / p}=27 \text { or, } 3 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & 3^{1 / p}=1 \text { or, } 3^{1 / p}=\frac{1}{9} \Rightarrow \frac{1}{p}=0 \text { or }-2

\end{array}

\)

But, \(1 / p\) cannot be zero. So, \(p=-1 / 2\)

Example 3: Both the roots of the equation [CEE (Delhi) 2001]

\(

(x-a)(x-b)+(x-b)(x-c)+(x-c)(x-a)=0 \text { are always }

\)

(a) positive

(b) negative

(c) real

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) The given equation can be written as

\(

3 x^2-2 x(a+b+c)+a b+b c+c a=0

\)

Let \(D\) be its discriminant. Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& D=4(a+b+c)^2-12(a b+b c+c a) \\

\Rightarrow \quad & D=2\left\{(b-c)^2+(c-a)^2+(a-b)^2\right\} \geq 0

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the roots are real.

Example 4: If \(a, b, c \in R^{+}\)and \(2 b=a+c\), then check the nature of roots of equation \(\boldsymbol{a} \boldsymbol{x}^{\mathbf{2}}+\mathbf{2} \boldsymbol{b} \boldsymbol{x}+\boldsymbol{c}=\mathbf{0}\).

Solution: Given equation is \(a x^2+2 b x+c=0\). Hence,

\(

\begin{aligned}

D & =4 b^2-4 a c \\

& =(a+c)^2-4 a c \\

& =(a-c)^2>0

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus, the roots are real and distinct.

Example 5: If the roots of the equation \(a(b-c) x^2 +b(c-a) x+c(a-b)=0\) are equal, show that \(2 / b=1 / a +1 / c\).

Solution: Since the roots of the given equations are equal, therefore its discriminant is zero, i.e.,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& b^2(c-a)^2-4 a(b-c) c(a-b)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & b^2\left(c^2+a^2-2 a c\right)-4 a c\left(b a-c a-b^2+b c\right)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & a^2 b^2+b^2 c^2+4 a^2 c^2+2 b^2 a c-4 a^2 b c-4 a b c^2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (a b+b c-2 a c)^2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & a b+b c-2 a c=0 \\

\Rightarrow & a b+b c=2 a c \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{1}{c}+\frac{1}{a}=\frac{2}{b} \quad[\text { Dividing both sides by } a b c] \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{2}{b}=\frac{1}{a}+\frac{1}{c}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 6: If \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c, g(x)=-a x^2+b x +c\), where \(a c \neq 0\), then prove that \(f(x) g(x)=0\) has at least two real roots.

Solution: Let \(D_1\) and \(D_2\), be discriminants of \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) and \(-a x^2 +b x+c=0\), respectively. Then,

\(

D_1=b^2-4 a c, D_2=b^2+4 a c

\)

Now,

\(

a c \neq 0 \Rightarrow \text { either } a c>0 \text { or } a c<0

\)

If \(a c>0\), then \(D_2>0\). Therefore, roots of \(-a x^2+b x+c=0\) are real.

If \(a c<0\), then \(D_1>0\). Therefore, roots of \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) are real.

Thus, \(f(x) g(x)\) has at least two real roots.

Example 7: If \(a, b, c \in R\) such that \(a+b+c=0\) and \(a \neq c\), then prove that the roots of \((b+c-a) x^2+(c+a-b) x +(a+b-c)=0\) are real and distinct.

Solution: Given equation is

\(

(b+c-a) x^2+(c+a-b) x+(a+b-c)=0

\)

\(

(-2 a) x^2+(-2 b) x+(-2 c)=0

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad \begin{aligned}

& a x^2+b x+c=0 \\

& D=b^2-4 a c \\

&=(-c-a)^2-4 a c

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{aligned}

& =(c-a)^2 >0

\end{aligned}\\

&\text { Hence, roots are real and distinct. }

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 8: If \(\cos \theta, \sin \phi, \sin \theta\) are in G.P., then check the nature of roots of \(x^2+2 \cot \phi \cdot x+1=0\).

Solution: We have,

\(

\sin ^2 \phi=\cos \theta \sin \theta

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { The discriminant of the given equation is }\\

&\begin{aligned}

& D=4 \cot ^2 \phi-4 \\

& =4\left[\frac{\cos ^2 \phi-\sin ^2 \phi}{\sin ^2 \phi}\right] \\

& =\frac{4\left(1-2 \sin ^2 \phi\right)}{\sin ^2 \phi} \\

& =\frac{4(1-2 \sin \theta \cos \theta)}{\sin ^2 \phi} \\

& =\left[\frac{2(\sin \theta-\cos \theta)}{\sin \phi}\right]^2 \geq 0

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 9: If \(a, b\) and \(c\) are odd integers, then prove that roots of \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) cannot be rational.

Solution: Discriminant \(D=b^2-4 a c\). Suppose the roots are rational. Then, \(D\) will be a perfect square.

Let \(b^2-4 a c=d^2\). Since \(a, b\) and \(c\) are odd integers, \(d\) will be odd. Now,

\(

b^2-d^2=4 a c

\)

Let \(b=2 k+1\) and \(d=2 m+1\). Then

\(

\begin{aligned}

b^2-d^2 & =(b-d)(b+d) \\

& =2(k-m) 2(k+m+1)

\end{aligned}

\)

Now, either \((k-m)\) or \((k+m+1)\) is always even. Hence \(b^2-d^2\) is always a multiple of 8. But, \(4 a c\) is only a multiple of 4 (not of 8 ), which is a contradiction. Hence, the roots of \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) cannot be rational.

Example 10: If the roots of the quadratic equation \(x^2-4 x-\log _3 a=0\) are real, then the least value of \(a\) is

(a) 81

(b) \(1 / 81\)

(c) \(1 / 64\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) Since the roots of the given equation are real.

\(\therefore \quad\) Discriminant \(>0\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad 16+4 \log _3 a \geq 0 \Rightarrow \log _3 a \geq-4 \Rightarrow a \geq 3^{-4} \Rightarrow a \geq 1 / 81\)

Hence, the least value of \(a\) is \(1 / 81\).

Relations Between Roots and Coefficients

Let \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) be the roots of quadratic equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\). Then by factor theorem,

\(

a x^2+b x+c=a(x-\alpha)(x-\beta)=a\left(x^2-(\alpha+\beta) x+a \beta\right)

\)

Comparing coefficients, we have \(\alpha+\beta=-b / a\) and \(\alpha \beta=c / a\). Thus, we find that

\(

\alpha+\beta=\frac{-b}{a}=-\frac{\text { coeff of } x}{\text { coeff of } x^2} \text { and } \alpha \beta=\frac{c}{a}=\frac{\text { constant term }}{\text { coeff of } x^2}

\)

Note: Also, if sum of roots is \(S\) and product is \(P\), then quadratic equation is given by \(x^2-S x+P=0\).

Example 11: Form a quadratic equation whose roots are -4 and 6.

Solution: We have sum of the roots, \(S=-4+6=2\) and, product of the roots, \(P=-4 \times 6=-24\). Hence, the required equation is

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2-S x+P=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & x^2-2 x-24=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 12: Find the quadratic equation with rational coefficients whose one root is \(1 /(2+\sqrt{5})\).

Solution: If the coefficients are rational, then irrational roots occur in conjugate pair. Given that if one root is \(\alpha=1 /(2+\sqrt{5})=\sqrt{5}-2\), then the other root is \(\beta=1 /(2-\sqrt{5})=-(2+\sqrt{5})\).

Sum of roots \(\alpha+\beta=-4\) and product of roots \(\alpha \beta=-1\). Thus, required equation is \(x^2+4 x-1=0\).

Example 13: Form a quadratic equation with real coefficients whose one root is \(\mathbf{3}-\mathbf{2} \boldsymbol{i}\).

Solution: Since the complex roots always occur in pairs, so the other root is \(3+2 i\). The sum of the roots is \((3+2 i)+(3-2 i)=6\). The product of the roots is \((3+2 i)(3-2 i)=9-4 i^2=9+4=13\).

Hence, the equation is

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2-S x+P=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & x^2-6 x+13=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 14: If \(a, b\) and \(c\) are in A.P. and one root of the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) is 2, then find the other root.

Solution: Let \(\alpha\) be the other root. Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 4 a+2 b+c=0 \text { and } 2 b=a+c \\

\Rightarrow & 5 a+2 c=0 \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{c}{a}=\frac{-5}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 2 \times \alpha=\frac{c}{a}=-\frac{5}{2} \\

\therefore \quad & \alpha=-\frac{5}{4}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 15: If the roots of the quadratic equation \(x^2 +p x+q=0\) are \(\tan 30^{\circ}\) and \(\tan 15^{\circ}\), respectively, then find the value of \(2+q-p\).

Solution: The equation \(x^2+p x+q=0\) has roots \(\tan 30^{\circ}\) and \(\tan 15^{\circ}\).

Therefore,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \tan 30^{\circ}+\tan 15^{\circ}=-p \dots(1)\\

& \tan 30^{\circ} \tan 15^{\circ}=q \dots(2)

\end{aligned}

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \tan 45^{\circ}=\tan \left(30^{\circ}+15^{\circ}\right) \\

\Rightarrow & 1=\frac{\tan 30+\tan 15}{1-\tan 30 \tan 15} \\

\Rightarrow & 1=\frac{-p}{1-q} \quad \text { [Using (1) and (2)] } \\

\Rightarrow & 1-q=-p \Rightarrow q-p=1

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad 2+q-p=3

\)

Note: For a quadratic equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) with roots \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), the sum of the roots is \(\alpha+\beta=-\frac{b}{a}\) and the product of the roots is \(\alpha \beta=\frac{c}{a}\).

For the equation \(x^2+p x+q=0\), the roots are \(\tan 30^{\circ}\) and \(\tan 15^{\circ}\).

The sum of the roots is \(\tan 30^{\circ}+\tan 15^{\circ}=-p\).

Example 16: Solve the equation \(x^2+p x+45=0\). It is given that the squared difference of its roots is equal to 144.

Solution: Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the roots of the equation \(x^2+p x+45=0\). Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \alpha+\beta=-p \\

& \alpha \beta=45

\end{aligned}

\)

It is given that

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (\alpha-\beta)^2=144 \\

\Rightarrow & (\alpha+\beta)^2-4 \alpha \beta=144 \\

\Rightarrow & p^2-4 \times 45=144 \\

\Rightarrow & p^2=324 \\

\Rightarrow & p= \pm 18

\end{aligned}

\)

Substituting \(p=18\) in the given equation, we obtain

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& x^2+18 x+45=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (x+3)(x+15)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & x=-3,-15

\end{array}

\)

Substituting \(p=-18\) in the given equation, we obtain

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& x^2+18 x+45=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (x-3)(x-15)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & x=3,15

\end{array}

\)

Hence, the roots of the given equation are \(-3,-15\) or 3,15.

Example 17: The harmonic mean of the roots of the equation \((5+\sqrt{2}) x^2-(4+\sqrt{5}) x+(8+2 \sqrt{5})=0\) is [IIT 1999, JEE (WB) 2007]

(a) 2

(b) 4

(c) 7

(d) 8

Solution: (b) Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the roots of the given equation. Then, \(\alpha+\beta=\frac{4+\sqrt{5}}{5+\sqrt{2}}\) and \(\alpha \beta=\frac{8+2 \sqrt{5}}{5+\sqrt{2}}\)

Let \(H\) be the H.M. of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\). Then,

\(

H=\frac{2 \alpha \beta}{\alpha+\beta}=\frac{16+4 \sqrt{5}}{4+\sqrt{5}}=4

\)

Note: Harmonic mean \(H=\frac{n}{\frac{1}{x_1}+\frac{1}{x_2}+\ldots+\frac{1}{x_n}}\)

Example 18: If \(a\) and \(b(\neq 0)\) are the roots of the equation \(x^2+a x+b=0\), then find the least value of \(x^2+a x+b (x \in R)\).

Solution: Since \(a\) and \(b\) are the roots of the equation \(x^2+a x+b =0\), so

\(

a+b=-a, a b=b

\)

Now,

\(

a b=b \Rightarrow(a-1) b=0 \Rightarrow a=1 \quad(\because b \neq 0)

\)

Putting \(a=1\) in \(a+b=-a\), we get \(b=-2\). Hence,

\(

\begin{aligned}

x^2+a x+b & =x^2+x-2=(x+1 / 2)^2-1 / 4-2 \\

& =(x+1 / 2)^2-9 / 4

\end{aligned}

\)

which has a minimum value \(-9 / 4\).

Example 19: If \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are the roots of the equation \(x^2-p(x+1)-q=0\), then the value of

\(

\frac{\alpha^2+2 \alpha+1}{\alpha^2+2 \alpha+q}+\frac{\beta^2+2 \beta+1}{\beta^2+2 \beta+q} \text { is }

\)

(a) 1

(b) 2

(c) 3

(d) 0

[CEE (Delhi) 1998, 2002]

Solution: (a) The given equation is

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& x^2-p x-(p+q)=0 \\

\therefore & \alpha+\beta=p \text { and } \alpha \beta=-(p+q) \\

\Rightarrow & \alpha \beta+\alpha+\beta=-q \\

\Rightarrow & \alpha \beta+\alpha+\beta+1=-q+1 \\

\Rightarrow & (\alpha+1)(\beta+1)=1-q \dots(i)

\end{array}

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{\alpha^2+2 \alpha+1}{\alpha^2+2 \alpha+q}+\frac{\beta^2+2 \beta+1}{\beta^2+2 \beta+q} \\

& =\frac{(\alpha+1)^2}{(\alpha+1)^2+q-1}+\frac{(\beta+1)^2}{(\beta+1)^2+(q-1)} \\

& =\frac{(\alpha+1)^2}{(\alpha+1)^2-(\alpha+1)(\beta+1)}+\frac{(\beta+1)^2}{(\beta+1)^2-(\alpha+1)(\beta+1)}[\text { Using (i) }] \\

& =\frac{\alpha+1}{\alpha-\beta}+\frac{\beta+1}{\beta-\alpha}=\frac{\alpha-\beta}{\alpha-\beta}=1

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 20: If the harmonic mean between roots of \((5+\sqrt{2}) x^2-b x+8+2 \sqrt{5}=0\) is 4, then find the value of \(b\).

Solution: Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the roots of the given equation whose H.M. is 4. Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

4 & =\frac{2 \alpha \beta}{\alpha+\beta} \\

\Rightarrow 4 & =2 \times \frac{\frac{8+2 \sqrt{5}}{5+\sqrt{2}}}{\frac{b}{5+\sqrt{2}}} \\

\Rightarrow 2 & =\frac{8+2 \sqrt{5}}{b} \Rightarrow b=4+\sqrt{5}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 21: If \(\alpha, \beta\) are the roots of the equation \(2 x^2-3 x-6=0\), find the equation whose roots are \(\alpha^2+2\) and \(\boldsymbol{\beta}^{\mathbf{2}} \boldsymbol{+} \boldsymbol{2}\).

Solution: Since \(\alpha, \beta\) are roots of the equation \(2 x^2-3 x-6=0\), so \(\alpha+\beta=3 / 2\) and \(\alpha \beta=-3\)

\(

\Rightarrow \alpha^2+\beta^2=(\alpha+\beta)^2-2 \alpha \beta=\frac{9}{4}+6=\frac{33}{4}

\)

Now,

\(

\left(\alpha^2+2\right)+\left(\beta^2+2\right)=\left(\alpha^2+\beta^2\right)+4=\frac{33}{4}+4=\frac{49}{4}

\)

and

\(

\begin{aligned}

\left(\alpha^2+2\right)\left(\beta^2+2\right) & =\alpha^2 \beta^2+2\left(\alpha^2+\beta^2\right)+4 \\

& =(3)^2+2\left(\frac{33}{4}\right)+4 \\

& =\frac{59}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

So, the equation whose roots are \(\alpha^2+2\) and \(\beta^2+2\) is

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2-x\left[\left(\alpha^2+2\right)+\left(\beta^2+2\right)\right]+\left(\alpha^2+2\right)\left(\beta^2+2\right)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-\frac{49}{4} x+\frac{59}{2}=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 4 x^2-49 x+118=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 22: If \(\alpha \neq \beta\) and \(\alpha^2=5 \alpha-3\) and \(\beta^2=5 \beta-3\), find the equation whose roots are \(\alpha / \beta\) and \(\beta / \alpha\).

Solution: We have \(\alpha^2=5 \alpha-3\) and \(\beta^2=5 \beta-3\). Hence, \(\alpha, \beta\) are roots of \(x^2=5 x-3\), i.e., \(x^2-5 x+3=0\). Therefore,

\(

\alpha+\beta=5 \text { and } \alpha \beta=3

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

S=\frac{\alpha}{\beta}+\frac{\beta}{\alpha} & =\frac{\alpha^2+\beta^2}{\alpha \beta} \\

& =\frac{(\alpha+\beta)^2-2 \alpha \beta}{\alpha \beta} \\

& =\frac{25-6}{3}=\frac{19}{3}

\end{aligned}

\)

and

\(

P=\frac{\alpha}{\beta} \frac{\beta}{\alpha}=1

\)

So, the required equation is

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2-S x+P=0 \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-\frac{19}{3} x+1=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 3 x^2-19 x+3=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Common Roots

Condition for One Common Root

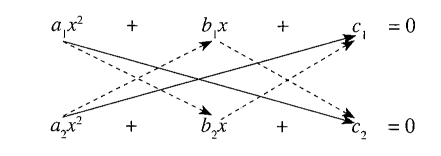

Let us find the condition that the quadratic equations \(a_1 x^2+b_1 x +c_1=0\) and \(a_2 x^2+b_2 x+c_2=0\) may have a common root. Let \(\alpha\) be the common root of the given equations. Then,

\(

a_1 \alpha^2+b_1 \alpha+c_1=0

\)

and \(a_2 \alpha^2+b_2 \alpha+c_2=0\)

Solving these two equations by cross-multiplication, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{\alpha^2}{b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1}=\frac{\alpha}{c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1}=\frac{1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1} \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \alpha^2=\frac{b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1} \quad \text { (from first and third) }

\end{aligned}

\)

and

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \alpha=\frac{c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1} \quad \text { (from second and third) } \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}=\left(\frac{c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}\right)^2 \\

\Rightarrow & \left(c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1\right)^2=\left(b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1\right)\left(a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

This condition can easily be remembered by cross-multiplication method as shown in the following figure.

(Bigger cross product) \(^2\)\(=\) Product of the two smaller crosses

This is the condition required for a root to be common to two quadratic equations. The common root is given by

\(

\alpha=\frac{c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}

\)

or \(\alpha=\frac{b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1}{c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1}\)

Example 23: Determine the values of \(\boldsymbol{m}\) for which the equations \(3 x^2+4 m x+2=0\) and \(2 x^2+3 x-2=0\) may have a common root.

Solution: Let \(\alpha\) be the common root of the equations \(3 x^2+4 m x+2 =0\) and \(2 x^2+3 x-2=0\). Then, \(\alpha\) must satisfy both the equations. Therefore,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 3 \alpha^2+4 m \alpha+2=0 \\

& 2 \alpha^2+3 \alpha-2=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Using cross-multiplication method, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (-6-4)^2=(9-8 m)(-8 m-6) \\

\Rightarrow & 50=(8 m-9)(4 m+3) \\

\Rightarrow & 32 m^2-12 m-77=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 32 m^2-56 m+44 m-77=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 8 m(4 m-7)+11(4 m-7)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (8 m+11)(4 m-7)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & m=-\frac{11}{8}, \frac{7}{4}

\end{aligned}

\)

Condition for Both the Common Roots

Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the common roots of the quadratic equations \(a_1 x^2 +b_1 x+c_1=0\) and \(a_2 x^2+b_2 x+c_2=0\). Then, both the equations are identical, hence,

\(

\frac{a_1}{a_2}=\frac{b_1}{b_2}=\frac{c_1}{c_2}

\)

Example 24: If \(x^2+3 x+5=0\) and \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) have common root/roots and \(a, b, c \in N\), then find the minimum value of \(a+b+c\).

Solution: The first quadratic equation is \(x^2+3 x+5=0\). To find its roots, we use the quadratic formula \(x=\frac{-B \pm \sqrt{B^2-4 A C}}{2 A}\). For this equation, \(A=1, B=3\), and \(C=5\).

The discriminant is \(\boldsymbol{D}=\boldsymbol{B}^2-4 \boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{C}=3^2-4(1)(5)=9-20=-11\). Since the discriminant is negative, the roots are complex conjugates:

\(

x=\frac{-3 \pm \sqrt{-11}}{2}=\frac{-3 \pm i \sqrt{11}}{2} .

\)

Therefore roots of \(x^2+3 x+5=0\) are non-real. Thus given equations will have two common roots. We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{a}{1}=\frac{b}{3}=\frac{c}{5}=\lambda \\

\Rightarrow & a+b+c=9 \lambda

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus minimum value of \(a+b+c\) is 9.

Note: The second equation is \(a x^2+b x+c=0\), with coefficients \(a, b, c \in N\). Since the coefficients are natural numbers, they are also real. For a quadratic equation with real coefficients to have a common root with another equation with complex roots, both equations must share both roots. This means the two equations must be proportional.

Therefore, the second equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) must have the same roots as \(x^2+3 x+5=0\). This implies that the ratio of corresponding coefficients is constant.

Example 25: If \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) and \(b x^2+c x+a=0\) have a common root and \(\boldsymbol{a}, \boldsymbol{b}\) and \(\boldsymbol{c}\) are non-zero real numbers then find the value of \(\left(a^3+b^3+c^3\right) / a b c\).

Solution: Given that \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) and \(b x^2+c x+a=0\) have a common root. Hence,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(b c-a^2\right)^2=\left(a b-c^2\right)\left(a c-b^2\right) \\

\Rightarrow & b^2 c^2+a^4-2 a^2 b c=a^2 b c-a b^3-a c^3+b^2 c^2 \\

\Rightarrow & a^4+a b^3+a c^3=3 a^2 b c

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad \frac{a^3+b^3+c^3}{a b c}=3

\)

Arithmetic Progression

An arithmetic progression is a sequence of numbers such tha the difference \(d\) between each consecutive term is a constant

\(

a, a+d, a+2 d, a+3 d, \ldots

\)

The \(\mathrm{n}^{\text {th }}\) term, \(T_n=a+(n-1) d\)

Sum of first n terms, \(S_n=\frac{n}{2}[2 a+(n-1) d]\)

Example 26: \(\boldsymbol{a}, \boldsymbol{b}, \boldsymbol{c}\) are positive real numbers forming a G.P. If \(a x^2+2 b x+c=0\) and \(d x^2+2 e x+f=0\) have a common root, then prove that \(d / a, e / b, f / c\) are in A.P.

Solution: Step 1: Find the common root

The numbers \(\boldsymbol{a}, \boldsymbol{b}, \boldsymbol{c}\) are in a geometric progression (G.P.), so \(\boldsymbol{b}^2=\boldsymbol{a} \boldsymbol{c}\). The first quadratic equation is given by \(a x^2+2 b x+c=0\). The discriminant of this equation is \(\Delta_1=(2 b)^2-4 a c=4 b^2-4 a c\). Since \(b^2=a c\), the discriminant is \(\Delta_1=4 a c-4 a c=0\). A quadratic equation with a discriminant of zero has exactly one repeated root. The root is given by \(x=\frac{-2 b}{2 a}=-\frac{b}{a}\).

Since the two given quadratic equations have a common root, this common root must be \(x=-\frac{b}{a}\).

Step 2: Substitute the common root into the second equation

The common root \(x=-\frac{\boldsymbol{b}}{\boldsymbol{a}}\) must also satisfy the second quadratic equation, \(d x^2+2 e x+f=0\). Substituting the value of \(x\) into this equation gives:

\(

\begin{gathered}

d\left(-\frac{b}{a}\right)^2+2 e\left(-\frac{b}{a}\right)+f=0 \\

\frac{d b^2}{a^2}-\frac{2 e b}{a}+f=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Since \(a, b, c\) are in a G.P., we have \(b^2=a c\). Substituting this into the equation, we get:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{d(a c)}{a^2}-\frac{2 e b}{a}+f=0 \\

& \frac{d c}{a}-\frac{2 e b}{a}+f=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 3: Rearrange the equation to show the arithmetic progression

Multiply the entire equation by \(\boldsymbol{a}\) to eliminate the denominators:

\(

\begin{gathered}

a\left(\frac{d c}{a}-\frac{2 e b}{a}+f\right)=a(0) \\

d c-2 e b+a f=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Rearranging the terms, we get:

\(

a f+d c=2 e b

\)

Dividing the entire equation by \(a c\), we have:

\(

\begin{gathered}

\frac{a f}{a c}+\frac{d c}{a c}=\frac{2 e b}{a c} \\

\frac{f}{c}+\frac{d}{a}=\frac{2 e}{b}

\end{gathered}

\)

This equation shows that the sum of the first and third terms is equal to twice the second term. This is the condition for \(d / a, e / b, f / c\) to be in an arithmetic progression (A.P.).

The final answer is that \(\boldsymbol{d} / \boldsymbol{a}, \boldsymbol{e} / \boldsymbol{b}, \boldsymbol{f} / \boldsymbol{c}\) are in an A.P. because they satisfy the condition that the sum of the first and third terms is twice the second term: \(\frac{d}{a}+\frac{f}{c}=2 \frac{e}{b}\).

Example 27: If the equations \(x^2+a x+12=0, x^2+b x +15=0\) and \(x^2+(a+b) x+36=0\) have a common positive root, then find the values of \(a\) and \(b\).

Solution: We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2+a x+12=0 \dots(1) \\

& x^2+b x+15=0 \dots(2)

\end{aligned}

\)

Adding (1) and (2), we get

\(

2 x^2+(a+b) x+27=0

\)

Now subtracting it from the third given equation, we get

\(

x^2-9=0 \Rightarrow x=3,-3

\)

Thus, common positive root is 3. Hence,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 9+12+3 a=0 \\

\Rightarrow & a=-7 \text { and } 9+3 b+15=0 \\

\Rightarrow & b=-8

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 28: The equations \(a x^2+b x+a=0\) and \(x^3-2 x^2+2 x-1=0\) have two roots common. Then find the value of \(\boldsymbol{a}+\boldsymbol{b}\).

Solution: By observation, \(x=1\) is a root of equation \(x^3-2 x^2+2 x-1 =0\). Thus we have

\(

(x-1)\left(x^2-x+1\right)=0

\)

Now roots of \(x^2-x+1=0\) are non-real.

Then equation \(a x^2+b x+a=0\) has both roots common with \(x^2-x+1=0\). Hence, we have

\(

\frac{a}{1}=\frac{b}{-1}=\frac{a}{1}

\)

or \(\quad a+b=0\)

Cubic Equation

If \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma\) are roots of a cubic equation \(a x^3+b x^2+c x+d=0\), then

\(

\alpha+\beta+\gamma=-\frac{b}{a}

\)

\(

\alpha \beta+\beta \gamma+\gamma \alpha=(-1)^2 \frac{c}{a}=\frac{c}{a}

\)

and,

\(

\alpha \beta \gamma=(-1)^3 \frac{d}{a}=-\frac{d}{a}

\)

Example 29: If the sum of two roots of the equation

\(

x^3-p x^2+q x-r=0

\)

is zero, then [CEE (Delhi) 2005]

(a) \(p q=r\)

(b) \(q r=p\)

(c) \(p r=q\)

(d) \(p q r=1\)

Solution: (a) Let the roots of the given equation be \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma\) such that \(\alpha+\beta=0\). Then,

\(

\alpha+\beta+\gamma=-\frac{(-p)}{1} \Rightarrow \alpha+\beta+\gamma=p \Rightarrow \gamma=p \quad[\because \alpha+\beta=0]

\)

But, \(\gamma\) is a root of the given equation.

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & \gamma^3-p \gamma^2+q \gamma-r=0 \\

\Rightarrow & p^3-p^3+q p-r=0 \quad [\because \gamma=p]\\

\Rightarrow & p q=r

\end{array}

\)

Example 30: If the roots \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma\) of the equation \(x^3-3 a x^2+3 b x-c=0\) are in H.P., then

(a) \(\beta=\frac{1}{\alpha}\)

(b) \(\beta=b\)

(c) \(\beta=\frac{c}{b}\)

(d) \(\beta=\frac{b}{c}\)

Solution: (c) Clearly, \(\frac{1}{\alpha}, \frac{1}{\beta}, \frac{1}{\gamma}\) are the roots of the equation \(-c x^3+3 b x^2-3 a x+1=0\) and are in A.P.

Now,

\(

\frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\beta}+\frac{1}{\gamma}=\frac{3 b}{c}

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \frac{3}{\beta}=\frac{3 b}{c} \quad\left[\because \frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\gamma}=\frac{2}{\beta}\right]

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad \beta=\frac{c}{b}

\)

Example 31: If the roots of the equation \(x^3-p x^2+q x-r=0\) are in A.P., then

(a) \(2 p^3=9 p q-27 r\)

(b) \(2 q^3=9 p q-27 r\)

(c) \(p^3=9 p q-27 r\)

(d) \(2 p^3=9 p q+27 r\)

Solution: (a) Let the roots of the given equation be \(a-d, a, a+d\). Then,

\(

(a-d)+a+(a+d)=-\frac{(-p)}{1} \Rightarrow a=\frac{p}{3}

\)

Since \(a\) is a root of the given equation.

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \therefore \quad a^3-p a^2+q a-r=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{p^3}{27}-\frac{p^3}{9}+\frac{q p}{3}-r=0 \Rightarrow 2 p^3-9 p q+27 r=0

\end{aligned}

\)

This is the required condition.

Example 32: If \(x^2+x+1\) is a factor of \(a x^3+b x^2+c x+d\), then the real root of \(a x^3+b x^2+c x+d=0\) is [CEE (Delhi) 2002]

(a) \(\frac{d}{a}\)

(b) \(-\frac{d}{a}\)

(c) \(-\frac{b}{a}\)

(d) \(-\frac{c}{a}\)

Solution: (b) It is given that \(x^2+x+1\) is a factor of \(a x^3+b x^2+c x+d\). Therefore, roots of \(x^2+x+1=0\) are also the roots of the equation \(a x^3+b x^2+c x+d=0\).

But, \(x^2+x+1=0\) has its roots as \(\omega\) and \(\omega^2\).

So, two imaginary roots of \(a x^3+b x^2+c x+d=0\) are \(\omega\) and \(\omega^2\).

Let the third real root be \(\alpha\). Then,

\(\omega \omega^2 \alpha=(-1)^3 \frac{d}{a} \Rightarrow \alpha=-\frac{d}{a}\)

Hence, the real root of \(a x^3+b x^2+c x+d=0\) is \(-\frac{d}{a}\).

Solving Cubic Equation

By using factor theorem together with some intelligent guessing, we can factorise polynomials of higher degree.

In summary, to solve a cubic equation of the form \(a x^3+b x^2 +c x+d=0\),

- Obtain one factor ( \(x-\alpha\) ) by trial and error.

- Factorize \(a x^3+b x^2+c x+d=0\) as \((x-\alpha)\left(h x^2+k x+s\right)=0\).

- Solve the quadratic expression for other roots.

Example 33: If \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma\) are the roots of the equation \(x^3+4 x+1=0\), then find the value of \((\alpha+\beta)^{-1}+(\beta+\gamma)^{-1} +(\gamma+\alpha)^{-1}\).

Solution: For the given equation \(\alpha+\beta+\gamma=0\),

\(

\alpha \beta+\beta \gamma+\alpha \gamma=4, \alpha \beta \gamma=-1

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

(\alpha+\beta)^{-1}+(\beta+\gamma)^{-1}+(\gamma+\alpha)^{-1} & =(-\gamma)^{-1}+(-\alpha)^{-1}+(-\beta)^{-1} \\

& =-\frac{\alpha \beta+\beta \gamma+\alpha \gamma}{\alpha \beta \gamma} \\

& =-\frac{4}{(-1)} \\

& =4

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 34: Let \(\alpha+i \beta(\alpha, \beta \in R)\) be a root of the equation \(x^3+q x+r=0, q, r \in R\). Find a real cubic equation, independent of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), whose one root is \(2 \alpha\).

Solution: If \(\alpha+i \beta\) is a root then, \(\alpha-i \beta\) will also be a root. If the third root is \(\gamma\), then

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (\alpha+i \beta)+(\alpha-i \beta)+\gamma=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \gamma=-2 \alpha

\end{aligned}

\)

But \(\gamma\) is a root of the given equation \(x^3+q x+r=0\). Hence,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (-2 \alpha)^3+q(-2 \alpha)+r=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & (2 \alpha)^3+q(2 \alpha)-r=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Therefore, \(2 \alpha\) is a root of \(t^3+q t-r=0\), which is independent of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\).

Example 35: In equation \(x^4-2 x^3+4 x^2+6 x-21=0\) if two of its roots are equal in magnitude but opposite in sign, find the roots.

Solution: Given that \(\alpha+\beta=0\) but \(\alpha+\beta+\gamma+\delta=2\). Hence,

\(

\gamma+\delta=2

\)

Let \(\alpha \beta=p\) and \(\gamma \delta=q\). Therefore, given equation is equivalent to \(\left(x^2+p\right)\left(x^2-2 x+q\right)=0\). Comparing the coefficients, we get

\(p+q=4,-2 p=6, p q=-21\). Therefore, \(p=-3, q=7\) and they satisfy \(p q=-21\). Hence,

\(

\left(x^2-3\right)\left(x^2-2 x+7\right)=0

\)

Therefore, the roots are \(\pm \sqrt{3}\) and \(1 \pm i \sqrt{6}\). (where \(i=\sqrt{-1}\) )

Example 36: Solve the equation \(x^3-13 x^2+15 x+189 =0\) if one root exceeds the other by 2.

Solution: Let the roots be \(\alpha, \alpha+2, \beta\). Sum of roots is \(2 \alpha+\beta+2=13\).

\(

\therefore \quad \beta=11-2 \alpha \dots(1)

\)

Sum of the product of roots taken two at a time is

\(

\alpha(\alpha+2)+(\alpha+2) \beta+\beta \alpha=15

\)

\(

\alpha^2+2 \alpha+2(\alpha+1) \beta=15 \dots(2)

\)

Product of the roots is

\(

\alpha \beta(\alpha+2)=-189 \dots(3)

\)

Eliminating \(\beta\) from (1) and (2), we get

\(

\alpha^2+2 \alpha+2(\alpha+1)(11-2 \alpha)=15

\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& 3 \alpha^2-20 \alpha-7=0 \\

\therefore & (\alpha-7)(3 \alpha+1)=0 \\

\therefore & \alpha=7 \text { or }-\frac{1}{3} \\

\therefore & \beta=-3, \frac{35}{3}

\end{array}

\)

Out of these values, \(\alpha=7, \beta=-3\) satisfy the third relation \(\alpha \beta(\alpha+2)=-189\), i.e., \((-21)(9)=-189\). Hence, the roots are 7 , \(7+2,-3\) or \(7,9,-3\).

Biquadratic Equations

If \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma, \delta\) are roots of the biquadratic equation \(a x^4+b x^3+c x^2+d x+e=0\), then

\(

\begin{aligned}

& S_1=\alpha+\beta+\gamma+\delta=-\frac{b}{a} \\

& S_2=\alpha \beta+\beta \gamma+\alpha \delta+\beta \gamma+\beta \delta+\gamma \delta=(-1)^2 \frac{c}{a}=\frac{c}{a}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& S_2=(\alpha+\beta)(\gamma+\delta)+\alpha \beta+\gamma \delta=\frac{c}{a} \\

& S_3=\alpha \beta \gamma+\beta \gamma \delta+\gamma \delta \alpha+\alpha \beta \delta=(-1)^3 \frac{d}{a}=-\frac{d}{a}

\end{aligned}

\)

or, \(\quad S_3=\alpha \beta(\gamma+\delta)+\gamma \delta(\alpha+\beta)=-\frac{d}{a}\)

and, \(S_4=\alpha \beta \gamma \delta=(-1)^4 \frac{e}{a}=\frac{e}{a}\).

Illustration: Step 1: Define a biquadratic equation

Let’s consider the biquadratic equation with roots \(\alpha=1, \beta=2, \gamma=3\), and \(\delta=4\). The polynomial can be written as \((x-1)(x-2)(x-3)(x-4)=0\).

Expanding this, we get:

\(

\begin{gathered}

\left(x^2-3 x+2\right)\left(x^2-7 x+12\right)=0 \\

x^4-7 x^3+12 x^2-3 x^3+21 x^2-36 x+2 x^2-14 x+24=0 \\

x^4-10 x^3+35 x^2-50 x+24=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Comparing this to the general form \(a x^4+b x^3+c x^2+d x+e=0\), we have \(a=1, b=-10, c=35, d=-50, e=24\).

Step 2: Calculate the sum of roots using the formulas

Using the formulas provided, we can find the sums of the roots.

\(

\begin{gathered}

S_1=\alpha+\beta+\gamma+\delta=-\frac{b}{a}=-\frac{-10}{1}=10 \\

S_2=\alpha \beta+\alpha \gamma+\alpha \delta+\beta \gamma+\beta \delta+\gamma \delta=\frac{c}{a}=\frac{35}{1}=35 \\

S_3=\alpha \beta \gamma+\alpha \beta \delta+\alpha \gamma \delta+\beta \gamma \delta=-\frac{d}{a}=-\frac{-50}{1}=50 \\

S_4=\alpha \beta \gamma \delta=\frac{e}{a}=\frac{24}{1}=24

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 3: Verify the results with the given roots

Now we will calculate the sums directly using the chosen roots \(\alpha=1, \beta=2, \gamma=3, \delta=4\).

\(

\begin{gathered}

S_1=1+2+3+4=10 \\

S_2=(1)(2)+(1)(3)+(1)(4)+(2)(3)+(2)(4)+(3)(4)=2+3+4+6+8+12=35 \\

S_3=(1)(2)(3)+(1)(2)(4)+(1)(3)(4)+(2)(3)(4)=6+8+12+24=50 \\

S_4=(1)(2)(3)(4)=24

\end{gathered}

\)

The calculated values from the formulas match the direct sum of the roots. Therefore, for the biquadratic equation \(x^4-10 x^3+35 x^2-50 x+24=0\), the relationships hold:

\(\mathrm{S}_1=10\)

\(\mathrm{S}_2=35\)

\(S_3=50\)

\(S_4=24\)

Formation Of a Polynomial Equation

If \(\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \alpha_3, \ldots, \alpha_n\) are the roots of an \(n\)th degree equation, then the equation is given by

\(

x^n-S_1 x^{n-1}+S_2 x^{n-2}-S_3 x^{n-3}+\ldots+(-1)^n S_n=0

\)

where \(S_k\) denotes the sum of the products of roots taken \(k\) at a time.

Particular Cases

Quadratic Equation

If \(\alpha, \beta\) are the roots of a quadratic equation, then the equation is

\(

x^2-S_1 x+S_2=0

\)

i.e.

\(

x^2-(\alpha+\beta) x+\alpha \beta=0

\)

Cubic Equation

If \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma\) are the roots of a cubic equation, then the equation is

\(

x^3-S_1 x^2+S_2 x-S_3=0

\)

i.e. \(\quad x^3-(\alpha+\beta+\gamma) x^2+(\alpha \beta+\beta \gamma+\gamma \alpha) x-\alpha \beta \gamma=0\)

Biquadratic Equation

If \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma, \delta\) are the roots of a biquadratic equation, then the equation is

\(

x^4-S_1 x^3+S_2 x^2-S_3 x+S_4=0

\)

i.e.

\(

\begin{aligned}

x^4-(\alpha+\beta+\gamma+\delta) & x^3+(\alpha \beta+\beta \gamma+\gamma \delta+\alpha \delta+\beta \delta+\alpha \gamma) x^2 \\

& -(\alpha \beta \gamma+\alpha \beta \delta+\beta \gamma \delta+\gamma \delta \alpha) x+\alpha \beta \gamma \delta=0

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

x^4-(\alpha+\beta+\gamma+\delta) & x^3+\{(\alpha+\beta)(\gamma+\delta)+\alpha \beta+\gamma \delta\} x^2 \\

& -\{(\alpha+\beta) \gamma \delta+\alpha \beta(\gamma+\delta)\} x+\alpha \beta \gamma \delta=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 37: If A, G and H are respectively the A.M., G.M. and H.M. of three positive numbers \(a, b\) and \(c\), then the equation whose roots are \(a, b, c\) is

(a) \(x^3-3 A x^2+\frac{3 G^3}{H} x-G^3=0\)

(b) \(x^3+3 A x^2+\frac{3 G^3}{H} x-G^3=0\)

(c) \(x^3+A x^2+\frac{G^3}{H}-G^3=0\)

(d) \(x^3-3 A x^2-\frac{3 G^3}{H} x-G^3=0\)

Solution: (a) By definition, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

A & =\frac{a+b+c}{3} \Rightarrow a+b+c=3 A \dots(i)\\

G & =(a b c)^{1 / 3} \Rightarrow a b c=G^3 \dots(ii) \\

\text { and, } \frac{1}{H} & =\frac{\frac{1}{a}+\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c}}{3} \\

\Rightarrow \quad \frac{3}{H} & =\frac{b c+c a+a b}{a b c} \\

\Rightarrow \quad \frac{3}{H} & =\frac{a b+b c+c a}{G^3} \Rightarrow a b+b c+c a=\frac{3 G^3}{H} \dots(iii)

\end{aligned}

\)

The equation whose roots are \(a, b\) and \(c\) is

\(

x^3-S_1 x^2+S_2 x-S_3=0

\)

or, \(\quad x^3-(a+b+c) x^2+(a b+b c+c a) x-a b c=0\)

or, \(x^3-3 A x^2+\frac{3 G^3}{H} x-G^3=0\)

[Using (i), (ii) and (iii)]

Transformation of Equations

Case-I: An equation whose roots are reciprocals of the roots of a given equation is obtained by replacing \(x\) by \(1 / x\) in the given equation.

Example 38: The quadratic equation whose roots are reciprocal of the roots of the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) is

(a) \(c x^2+b x+a=0\)

(b) \(b x^2+c x+a=0\)

(c) \(c x^2+a x+b=0\)

(d) \(b x^2+a x+c=0\)

Solution: (a) The quadratic equation whose roots are reciprocal of the roots of the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) is obtained by replacing \(x\) by \(1 / x\). Thus, the required equation is

\(\frac{a}{x^2}+\frac{b}{x}+c=0\) or, \(c x^2+b x+a=0\).

Example 39: If the roots of the equation \(x^3-p x^2+q x-r=0\) are in H.P., then

(a) \(27 r^2+9 p q r+2 q^3=0\)

(b) \(27 r^2-9 p q r+2 q^3=0\)

(c) \(2 r^2-9 p q r+27 q^3=0\)

(d) \(27 r^2-9 p q r-2 q^3=0\)

Solution: (b) The equation whose roots are reciprocals of the roots of the given equation is given by

\(

\frac{1}{x^3}-\frac{p}{x^2}+\frac{q}{x}-r=0 \Rightarrow r x^3-q x^2+p x-1=0 \dots(i)

\)

Since the roots of the given equation are in H.P. Therefore, the roots of equation (i) are in A.P. Let its roots be \(a-d, a\) and \(a+d\). Then,

\(

(a-d)+a+(a+d)=-\left(-\frac{q}{r}\right) \Rightarrow 3 a=\frac{q}{r} \Rightarrow a=\frac{q}{3 r}

\)

Since \(a\) is a root of equation (i).

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \therefore \quad r a^3-q a^2+p a-1=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad r\left(\frac{q}{3 r}\right)^3-q\left(\frac{q}{3 r}\right)^2+p\left(\frac{q}{3 r}\right)-1=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{q^3}{27 r^2}-\frac{q^3}{9 r^2}+\frac{p q}{3 r}-1=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad q^3-3 q^3+9 p q r-27 r^2=0 \Rightarrow 27 r^2-9 p q r+2 q^3=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Case-II: An equation whose roots are negative of the roots of a given equation is obtained by replacing \(x\) by \(-x\) in the given equation.

Case-III: An equation whose roots are squares of the roots of a given equation is obtained by replacing \(x\) by \(\sqrt{x}\) in the given equation.

Case-IV: An equation whose roots are cubes of the roots of a given equation is obtained by replacing \(x\) by \(x^{1 / 3}\) in the given equation.

Condition for Resolution of a Quadratic Function into Linear Factors (Quadratic Expression in two variables)

The quadratic function

\(

a x^2+2 h x y+b y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c

\)

is resolvable into linear rational factors iff

\(

a b c+2 f g h-a f^2-b g^2-c h^2=0 \text { i.e. }\left|\begin{array}{lll}

a & h & g \\

h & b & f \\

g & f & c

\end{array}\right|=0

\)

Proof: The equation corresponding to the given quadratic function \(a x^2+2 h x y+b y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c\) is

\(

\begin{aligned}

a x^2+2 h x y+b y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c & =0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad a x^2+2 x(h y+g)+b y^2+2 f y+c & =0

\end{aligned}

\)

Solving for \(x\), we get

\(

x=\frac{-2(h y+g) \pm \sqrt{4(h y+g)^2-4 a\left(b y^2+2 f y+c\right)}}{2 a}, \text { where } a \neq 0

\)

The given expression will have linear rational factors only if the values of \(x\) are rational linear expression in \(y\). This is possible only when the roots of the above equation are real and equali.e.,

Discriminant \(D=0\).

or, \(4(h y+g)^2-4 a\left(b y^2+2 f y+c\right)=0\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad y^2\left(h^2-a b\right)+2(h g-a f) y+g^2-a c=0

\)

The roots of this equation are equal, if

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \quad \text { Discriminant }=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 4(h g-a f)^2-4\left(h^2-a b\right)\left(g^2-a c\right)=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a b c+2 f g h-a f^2-b g^2-c h^2=0

\end{aligned}

\)

This is the required condition.

Example 40: The values of \(m\) for which the expression

\(

2 x^2+m x y+3 y^2-5 y-2

\)

can be expressed as the product of two linear factors are

(a) \(\pm 7\)

(b) \(\pm 5\)

(c) \(\pm 4\)

(d) \(\pm 1\)

Solution: (a) Comparing the given equation with

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a x^2+2 h x y+b y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0, \text { we have } \\

& a=2, h=m / 2, b=3, c=-2, f=-5 / 2, g=0

\end{aligned}

\)

The given expression is resolvable into linear factors, if

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a b c+2 f g h-a f^2-b g^2-c h^2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & -12-\frac{25}{2}+2\left(\frac{m^2}{4}\right)=0 \Rightarrow m^2=49 \Rightarrow m= \pm 7

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 41: Find the linear factors of \(2 x^2-y^2-x +x y+2 y-1\).

Solution: Given expression is

\(

2 x^2-y^2-x+x y+2 y-1 \dots(1)

\)

Its corresponding equation is

\(

2 x^2-y^2-x+x y+2 y-1=0

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

2 x^2 & -(1-y) x-\left(y^2-2 y+1\right)=0 \\

\therefore \quad x & =\frac{1-y \pm \sqrt{(1-y)^2+4.2\left(y^2-2 y+1\right)}}{4} \\

& =\frac{1-y \pm \sqrt{(1-y)^2+8(y-1)^2}}{4} \\

& =\frac{1-y \pm \sqrt{9(1-y)^2}}{4} \\

& =\frac{1-y \pm 3(1-y)}{4} \\

& =1-y,-\frac{1-y}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the required linear factors are \((x+y-1)\) and \((2 x-y+1)\).

Example 42: If the expression \(a x^2+b y^2+c z^2+2 a y z +2 b z x+2 c x y\) can be resolved into rational factors, then \(a^3+b^3+c^3\) is equal to

(a) \(a b c\)

(b) \(3 a b c\)

(c) \(2 a b c\)

(d) \(-3 a b c\)

Solution: (b) The given expression is

\(

a x^2+b y^2+c z^2+2 a y z+2 b z x+2 c x y

\)

\(

=z^2\left\{a\left(\frac{x}{z}\right)^2+b\left(\frac{y}{z}\right)^2+c+2 a\left(\frac{y}{z}\right)+2 b\left(\frac{x}{z}\right)+2 c\left(\frac{x}{z}\right)\left(\frac{y}{z}\right)\right\}

\)

\(

=z^2\left\{a X^2+b Y^2+2 c X Y+2 b X+2 a Y+c\right\} \dots(i)

\)

where \(X=\frac{x}{z}\) and \(Y=\frac{y}{z}\).

The given expression can be resolved into rational factors if the expression within brackets in (i) is expressible into rational facors, the condition for which is

\(

a b c+2 a b c-a \times a^2-b \times b^2-c \times c^2=0 \Rightarrow a^3+b^3+c^3=3 a b c

\)

Finding Range of a function Involving Quadratic Expression

In this section, some examples are given to illustrate the range of a function involving quadratic expression.

Example 43: Find the range of the function \(f(x)=x^2 -2 x-4\).

Solution: Let

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2-2 x-4=y \\

\Rightarrow \quad & x^2-2 x-4-y=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Now if \(x\) is real, then

\(

\begin{aligned}

& D \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & (-2)^2-4(1)(-4-y) \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & 4+16+4 y \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & y \geq-5

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence range of \(f(x)\) is \([-5, \infty)\).

Alternative method:

\(

\begin{aligned}

f(x) & =x^2-2 x-4 \\

& =(x-1)^2-5 \\

& \geq-5

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, range is

\(

[-5, \infty)

\)

Example 44: Find the least value of \(\frac{\left(6 x^2-22 x+21\right)}{\left(5 x^2-18 x+17\right)}\) for real \(x\).

Solution: Let,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{6 x^2-22 x+21}{5 x^2-18 x+17}=y \\

\Rightarrow & (6-5 y) x^2-2 x(11-9 y)+21-17 y=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Since \(x\) is real

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 4(11-9 y)^2-4(6-5 y)(21-17 y) \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & -4 y^2+9 y-5 \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & 4 y^2-9 y+5 \leq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & 4(y-1)(y-5 / 4) \leq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & 1 \leq y \leq 5 / 4

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the least value of the given expression is 1.

Example 45: Find the domain and the range of

\(

f(x)=\sqrt{3-2 x-x^2}

\)

Solution: \(f(x)=\sqrt{3-2 x-x^2}\) is defined if

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 3-2 x-x^2 \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & x^2+2 x-3 \leq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & (x-1)(x+3) \leq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & x \in[-3,1]

\end{aligned}

\)

Also, \(f(x)=\sqrt{4-(x+1)^2}\) has maximum value when \(x+1 =0\). Hence range is \([0,2]\).

Example 46: Find the domain and range of

\(

f(x)=\sqrt{x^2-3 x+2} .

\)

Solution: \(x^2-3 x+2 \geq 0\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & (x-1)(x-2) \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & x \in(-\infty, 1] \cup[2, \infty)

\end{array}

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(x)=\sqrt{x^2-3 x+2} \\

& =\sqrt{\left(x-\frac{3}{2}\right)^2+2-\frac{9}{4}} \\

& =\sqrt{\left(x-\frac{3}{2}\right)^2-\frac{1}{4}}

\end{aligned}

\)

Now, the least permissible value of \((x-3 / 2)^2-1 / 4\) is 0 when \((x-3 / 2)= \pm 1 / 2\). Hence, the range is \([0, \infty)\).

Maximum and Minimum Value of rational Expressions

In order to find the values attained by a rational expression of the form \(\frac{a_1 x^2+b_1 x+c_1}{a_2 x^2+b_2 x+c_2}\) for real values of \(x\), we may follow the following algorithm.

Algorithm

- Step I: Equate the given rational expression to \(y\).

- Step II: Obtain a quadratic equation in \(x\) by simplifying the expression in step \(I\).

- Step III: Obtain the discriminant of the quadratic in step II.

- Step IV: Put Disc \(\geq 0\) and solve the inequation for \(y\). The values of \(y\) so obtained determine the set of values attained by the given rational expression.

Example 47: For real values of \(x\) the values of \(\frac{x^2-3 x+4}{x^2+3 x+4}\) lie in the interval

(a) \((0,1 / 7)\)

(b) \((7, \infty)\)

(c) \([1 / 7,7]\)

(d) \([-1 / 7,7]\)

Solution: (c) Let \(y=\frac{x^2-3 x+4}{x^2+3 x+4}\). Then,

\(

x^2(y-1)+3 x(y+1)+4(y-1)=0

\)

This equation gives the values of \(x\) for given values of \(y\). But, \(y\) is the value when \(x\) is real. So, the roots of this equation are real.

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{aligned}

& \therefore \quad 9(y+1)^2-16(y-1)^2 \geq 0 \quad \text { [Using Discriminant } \geq 0 \text { ] } \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 7 y^2-50 y+7 \leq 0 \Rightarrow(7 y-1)(y-7) \leq 0 \Rightarrow 1 / 7 \leq y \leq 7 .

\end{aligned}\\

&\text { Hence, the given expression lies between } 1 / 7 \text { and } 7 \text {. }

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 48: If \(x\) is real, then the values of \(\frac{x^2+34 x-71}{x^2+2 x-7}\) does not lie in the interval

(a) \([5,9]\)

(b) \((-\infty, 5]\)

(c) \([9, \infty)\)

(d) \(R-(5,9)\)

Solution: (d) Let \(y=\frac{x^2+34 x-71}{x^2+2 x-7}\). Then,

\(

x^2(y-1)+2 x(y-17)-(7 y-71)=0

\)

Since \(x\) is real. Therefore, the above equation has real roots.

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & 4(y-17)^2+4(y-1)(7 y-71) \geq 0 \quad \text { [Putting Disc } \geq 0 \text { ] } \\

\Rightarrow & y^2-14 y+45 \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & (y-5)(y-9) \geq 0 \Rightarrow y \leq 5 \text { or } y \geq 9 \Rightarrow y \in R-(5,9)

\end{array}

\)

Example 49: The maximum and minimum values of \(\frac{x^2+14 x+9}{x^2+2 x+3}\) are

(a) 3,1

(b) \(4,-5\)

(c) \(0,-\infty\)

(d) \(\infty,-\infty\)

Solution: (b) Let \(y=\frac{x^2+14 x+9}{x^2+2 x+3}\). Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2(y-1)+2 x(y-7)+3 y-9=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 4(y-7)^2-4(y-1)(3 y-9) \geq 0 \quad [\text { because } x \text { is real }]\\

\Rightarrow & y^2+y-20 \leq 0 \Rightarrow-5 \leq y \leq 4

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 50: The values of a for which the expression \(\frac{a x^2+3 x-4}{a+3 x-4 x^2}\) can assume all real values for real \(x\) lie in the interval

(a) \(a \leq 1\) or \(a \geq 7\)

(b) \(a \geq 1\) or \(a \leq 7\)

(c) \(1 \leq a \leq 7\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) Let \(y=\frac{a x^2+3 x-4}{a+3 x-4 x^2}\)

Then, \(y\) takes all real values for real values of \(x\).

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& y=\frac{a x^2+3 x-4}{a+3 x-4 x^2} \\

\Rightarrow & x^2(a+4 y)+3 x(1-y)-(4+a y)=0 \text { for all } y \in R \\

\Rightarrow & 9(1-y)^2-4(a+4 y)(4+a y) \geq 0 \text { for all } y \in R \\

& \quad \because x \in R \therefore \text { Disc } \geq 0] \\

\Rightarrow & \quad(9+16 a) y^2+\left(4 a^2+46\right) y+(9+16 a) \geq 0 \text { for all } y \in R \\

\Rightarrow & \quad 9+16 a>0 \text { and }\left(4 a^2+46\right)^2-4(9+16 a)^2 \leq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & \quad 9+16 a>0 \text { and } 4(a+4)^2\left(a^2-8 a+7\right) \leq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & \quad a \geq-\frac{9}{16} \text { and } a^2-8 a+7 \leq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & \quad a \geq-\frac{9}{16} \text { and } 1 \leq a \leq 7 \Rightarrow 1 \leq a \leq 7

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 51: The value of a for which the sum of the squares of the roots of the equation \(x^2-(a-2) x-a-1=0\) assumes the least value is [AIEEE 2005]

(a) 0

(b) 1

(c) 2

(d) 3

Solution: (b) Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the roots of the given equation. Then, \(\alpha+\beta=a-2\) and \(\alpha \beta=-(a+1)\).

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & \alpha^2+\beta^2=(\alpha+\beta)^2-2 \alpha \beta=(a-2)^2+2(a+1) \\

\Rightarrow & \alpha^2+\beta^2=a^2-2 a+6=(a-1)^2+5

\end{array}

\)

Clearly, \(\alpha^2+\beta^2 \geq 5\). So, the minimum value of \(\alpha^2+\beta^2\) is 5 which it attains at \(a=1\).

Example 51: In a triangle \(P Q R, \angle R=\pi / 2\). If \(\tan (P / 2)\) and \(\tan (Q / 2)\) are the roots of the equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0(a \neq 0)\), then [IIT 1999, AIEEE 2005]

(a) \(a+b=c\)

(b) \(b+c=0\)

(c) \(a+c=b\)

(d) \(b=c\)

Solution: (a) We have,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& \angle R=\frac{\pi}{2} \Rightarrow \angle P+\angle Q=\frac{\pi}{2} \Rightarrow \frac{P}{2}+\frac{Q}{2}=\frac{\pi}{4} \\

\therefore & \tan \left(\frac{P}{2}+\frac{Q}{2}\right)=\tan \frac{\pi}{4} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{\tan P / 2+\tan Q / 2}{1-\tan P / 2 \tan Q / 2}=1 \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{-\frac{b}{a}}{1-\frac{c}{a}}=1 \quad\left[\because \tan \frac{P}{2}+\tan \frac{Q}{2}=-\frac{b}{a} \text { and } \tan \frac{P}{2} \tan \frac{Q}{2}=\frac{c}{a}\right] \\

\Rightarrow & 1-\frac{c}{a}=-\frac{b}{a} \Rightarrow a-c=-b \Rightarrow a+b=c

\end{array}

\)

Example 52: For the equation \(3 x^2+p x+3=0, p>0\), if one of the roots is square of the other, then \(p\) is equal to [IIT (S) 2000]

(a) \(\frac{1}{3}\)

(b) 1

(c) 3

(d) \(2 / 3\)

Solution: (c) Let \(\alpha\) and \(\alpha^2\) be the roots of the given equation. Then

\(

\alpha+\alpha^2=-p / 3 \text { and } \alpha^3=1

\)

Now, \(\alpha^3=1 \Rightarrow \alpha=1, \omega, \omega^2\)

Thus, the roots of the given equation are \(\omega\) and \(\omega^2\). Therefore, \(\alpha=\omega\).

Now,

\(

\therefore \quad \alpha+\alpha^2=-\frac{p}{3} \Rightarrow \omega+\omega^2=-\frac{p}{3} \Rightarrow-1=-\frac{p}{3} \Rightarrow p=3

\)

Example 53: If \(b>a\), then the equation \((x-a)(x-b)-1=0\), has [IIT (S) 2000]

(a) both roots in \([a, b]\)

(b) both roots in \((-\infty, a]\)

(c) both roots in ( \(b, \infty\) ]

(d) one roots in \((-\infty, a)\) and other in ( \(b, \infty\) )

Solution: (d) Let \(f(x)=(x-a)(x-b)-1\).

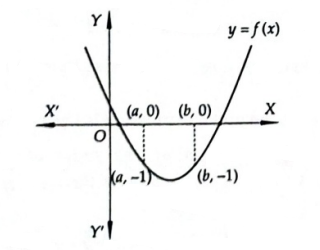

We observe that the coefficient of \(x^2\) in \(f(x)\) is positive and \(f(a)=f(b)=-1\). Thus the graph of \(f(x)\) is as shown in Figure below.

It is evident from the graph that one of the roots of \(f(x)=0\) lies in ( \(-\infty, a\) ) and the other lies in ( \(b, \infty\) ).

Example 54: Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the roots of the equation \(x^2-x+p=0\) and \(\gamma, \delta\) be the roots of the equation \(x^2-4 x+q=0\). If \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma, \delta\) are in G.P., then the integral values of \(p\) and \(q\) respectively, are [IIT (S) 2001]

(a) \(-2,-32\)

(b) \(-2,3\)

(c) \(-6,3\)

(d) \(-6,-32\)

Solution: (a) Since \(\alpha, \beta\) are the roots of the equation \(x^2-x+p=0\) and \(\gamma, \delta\) are the roots of the equation \(x^2-4 x+q=0\). Therefore,

\(

\alpha+\beta=1, \alpha \beta=p, \gamma+\delta=4, \gamma \delta=q

\)

Let \(r\) be the common ratio of the G.P. \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma, \delta\). Then,

\(

\beta=\alpha r, \gamma=\alpha r^2 \text { and } \delta=\alpha r^3 .

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \alpha+\beta=1 \Rightarrow \alpha+\alpha r=1 \\

& \gamma+\delta=4 \Rightarrow \alpha r^2+\alpha r^3=4 \\

& \therefore \quad \frac{\alpha r^2+\alpha r^3}{\alpha+\alpha r}=4 \Rightarrow r^2=4 \Rightarrow r= \pm 2 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Case I: When \(r=2\)

In this case, we have

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& \alpha+\beta=1 \\

\Rightarrow & \alpha+\alpha r=1 \Rightarrow 3 \alpha=1 \Rightarrow \alpha=\frac{1}{3} \quad[\because r=2] \\

\therefore & p=\alpha \beta=\alpha^2 r=\frac{2}{9}

\end{array}

\)

But, \(p\) is an integer. Therefore, \(r=2\) is not possible.

Case II: When \(r=-2\)

In this case, we have

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& \alpha+\beta=1 \\

\Rightarrow & \alpha+\alpha r=1 \Rightarrow-\alpha=1 \Rightarrow \alpha=-1 \\

\therefore & \alpha+\beta=1 \Rightarrow \beta=2

\end{array} \quad[\because r=-2]

\)

Now, \(p=\alpha \beta \Rightarrow p=-2\)

and, \(q=\gamma \delta=\left(\alpha r^2\right)\left(\alpha r^3\right)=-32\)

Hence, \(p=-2\) and \(q=-32\).

Example 55: Let \(p\) and \(q\) be roots of the equation \(x^2-2 x+A=0\) and let \(r\) and \(s\) be the roots of the equation \(x^2-18 x+B=0\). If \(p<q<r<s\) are in \(A\). \(P\)., then the values of \(A\) and \(B\) are [IIT 1997]

(a) \(A=3, B=77\)

(b) \(A=-3, B=77\)

(c) \(A=3, B=-17\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) Let \(p=a-3 d, q=a-d, r=a+d\) and \(s=a+3 d\), where \(d>0\).

Since \(p, q\) are the roots of \(x^2-2 x+A=0\).

\(

\therefore \quad p+q=2 \text { and } p q=A .

\)

It is given that \(r\) and \(s\) are the roots of \(x^2-18 x+B=0\).

\(

\therefore \quad r+s=18 \text { and } r s=B .

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& p+q=2 \text { and } r+s=18 \\

\Rightarrow & 2 a-4 d=2 \text { and } 2 a+4 d=18 \\

\Rightarrow & a-2 d=1 \text { and } a+2 d=9 \\

\Rightarrow & a=5, d=2 \Rightarrow p=-1, q=3 \cdot r=7 \text { and } s=11 \\

\therefore & A=p q=-3, \text { and } B=r s=77 .

\end{array}

\)

Example 56: If \(\alpha\) and \(\beta(\alpha<\beta)\) are the roots of the equation \(x^2+b x+c=0\), where \(c<0<b\), then [IIT (S) 2000]

(a) \(0<\alpha<\beta\)

(b) \(\alpha<0<\beta<|\alpha|\)

(c) \(\alpha<\beta<0\)

(d) \(\alpha<0<|\alpha|<\beta\)

Solution: (b) Since, \(\alpha, \beta\) are the roots of the equation \(x^2+b x+c=0\).

\(\therefore \quad \alpha+\beta=-b\) and \(\alpha \beta=c\).

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& c<0<b \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \alpha \beta<0 \text { and } \alpha+\beta<0

\end{aligned}

\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad\) One of the roots is positive and other is negative. It is given that \(\alpha<\beta\). Therefore, \(\alpha<0\) and \(\beta>0\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \alpha+\beta=-b \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \beta=-b-\alpha

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad \beta<-\alpha [\because b>0]

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad \beta<|\alpha| [\because \alpha<0, \therefore|\alpha|=-\alpha]

\)

Thus, \(\alpha<0<\beta<|\alpha|\).

Example 57: If \(f(x)=x^2+2 b x+2 c^2\) and \(g(x)=-x^2-2 c x+b^2\) be such that \(\min f(x)>\max g(x)\), then the relation between \(b\) and \(c\), is [IIT (S) 2003]

(a) no real values of \(b\) and \(c\)

(b) \(0<c<\sqrt{2} b\)

(c) \(|c|<\sqrt{2}|b|\)

(d) \(|c|>\sqrt{2}|b|\)

Solution: (d) If \(y=a x^2+b x+c\), then

\(y_{\text {min }}=-\left(\frac{b^2-4 a c}{4 a}\right)\), if \(a>0\) and \(y_{\text {max }}=-\left(\frac{b^2-4 a c}{4 a}\right)\), if \(a<0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \therefore \quad \operatorname{Min} f(x)>\operatorname{Max} g(x) \\

& \Rightarrow \quad-\left(\frac{4 b^2-8 c^2}{4}\right)>-\left(\frac{4 c^2+4 b^2}{-4}\right) \\

& \Rightarrow \quad\left(2 c^2-b^2\right)>\left(b^2+c^2\right) \\

& \Rightarrow \quad c^2-2 b^2>0 \Rightarrow c^2-(\sqrt{2}|b|)^2>0 \Rightarrow|c|>\sqrt{2}|b|

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 58: If one root is square of the other root of the equation \(x^2+p x+q=0\), then the relation between \(p\) and \(q\) is [IIT (s) 2004]

(a) \(p^3-(3 p-1) q+q^2=0\)

(b) \(p^3-(3 p+1) q+q^2=0\)

(c) \(p^3+(3 p-1) q+q^2=0\)

(d) \(p^3+(3 p+1) q+q^2=0\)

Solution: (a) Let \(\alpha, \alpha^2\) be the roots of the equation \(x^2+p x+q=0\). Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \alpha+\alpha^2=-p \text { and } \alpha \times \alpha^2=q \\

\Rightarrow & \alpha+\alpha^2=-p \text { and } \alpha=q^{1 / 3} \\

\Rightarrow & q^{1 / 3}+q^{2 / 3}=-p \\

\Rightarrow & \left(q^{1 / 3}+q^{2 / 3}\right)^3=-p^3 \\

\Rightarrow & q+q^2-3 p q=-p^3 \Rightarrow p^3-q(3 p-1)+q^2=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 59: If \((1-p)\) is a root of the quadratic equation \(x^2+p x+(1-p)=0\), then its roots are [AIEEE 2004]

(a) \(-1,2\)

(b) \(-1,1\)

(c) \(0,-1\)

(d) \(0,1\)

Solution: (c) Since \((1-p)\) is a root of the given equation.

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & (1-p)^2+p(1-p)+(1-p)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (1-p)\{(1-p)+p+1\}=0 \Rightarrow 2(1-p)=0 \Rightarrow p=1

\end{array}

\)

Substituting \(p=1\) in the given equation, we get

\(

x^2+x=0 \Rightarrow x=0,-1

\)

Hence, 0 and -1 are the roots of the given equation.

Example 60: If both the roots of the quadratic equation \(x^2-2 k x+k^2+k-5=0\) are less than 5 , then \(k\) lies in the interval [AIEEE 2005]

(a) \([4,5]\)

(b) \((-\infty, 4)\)

(c) \((6, \infty)\)

(d) \((5,6]\)

Solution: (b) Let \(f(x)=x^2-2 k x+k^2+k-5\). If both roots of the given quadratic equation are less than 5 , then we must have

(i) \(D \geq 0\)

(ii) \(f(5)>0\)

(iii) Vertex of \(y=f(x)\) lies on the left side of \((5,0)\)

Now,

(i) \(D \geq 0 \Rightarrow 4 k^2-4\left(k^2+k-5\right) \geq 0 \Rightarrow k-5 \leq 0 \Rightarrow k \leq 5 \dots(i)\)

(ii) \(f(5)>0 \Rightarrow k^2-9 k+20>0 \Rightarrow k<4\) or \(k>5 \dots(ii)\)

(iii) Vertex of \(y=f(x)\) lies on the left hand side of \((5,0)\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad k<5 \dots(iii)\)

From (i), (ii) and (iii), we get \(k \in(-\infty, 4)\)

Example 61: If the difference between the roots of the equation \(x^2+a x+1=0\) is less than \(\sqrt{5}\), then the set of possible values of \(a\) is [AIEEE 2007]

(a) \((3, \infty)\)

(b) \((-\infty,-3)\)

(c) \((-3,3)\)

(d) \((-3, \infty)\)

Solution: (c) Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the roots of the equation \(x^2+a x+1=0\).

Then,

\(

\alpha+\beta=-a \text { and } \alpha \beta=1

\)

Now, \(|\alpha-\beta|<\sqrt{5}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad(\alpha-\beta)^2<5 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(\alpha+\beta)^2-4 \alpha \beta<5 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a^2-4<5 \Rightarrow a^2-9<0 \Rightarrow-3<a<3

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 62: All the values of \(m\) for which both roots of the equation \(x^2-2 m x+m^2-1=0\) are greater than -2 but less than 4, lie in the interval [AIEEE 2006]

(a) \((-2,0)\)

(b) \((3, \infty)\)

(c) \((-1,3)\)

(d) \((1,4)\)

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2-2 m x+m^2-1=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & (x-m)^2=1 \Rightarrow x-m= \pm 1 \Rightarrow x=m \pm 1

\end{aligned}

\)

We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& -2<m-1<4 \text { and }-2<m+1<4 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & -1<m<5 \text { and }-3<m<3 \Rightarrow-1<m<3

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 63: If \(x\) is real, the maximum value of \(\frac{3 x^2+9 x+17}{3 x^2+9 x+7}\), is [AIEEE 2006]

(a) \(\frac{1}{4}\)

(b) 41

(c) 1

(d) \(\frac{17}{7}\)

Solution: (b) Let \(y=\frac{3 x^2+9 x+17}{3 x^2+9 x+7}\). Then,

\(

3 x^2(y-1)+9 x(y-1)+7 y-17=0

\)

Since \(x\) is real.

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & 81(y-1)^2-12(y-1)(7 y-17) \geq 0 \\

\Rightarrow & -3(y-1)(y-41) \geq 0 \Rightarrow(y-1)(y-41) \leq 0 \Rightarrow 1 \leq y \leq 41

\end{array}

\)

Hence, the maximum value of \(y\) is 41.

Example 64: If the roots of the equation \(b x^2+c x+a=0\) be imaginary, then for all real values of \(x\) the expression \(3 b^2 x^2+6 b c x+2 c^2\) is [AIEEE 2009]

(a) greater than \(4 a b\)

(b) less than \(4 a b\)

(c) greater than \(-4 a b\)

(d) less than \(-4 a b\)

Solution: (c) It is given that the roots of \(b x^2+c x+a=0\) are imaginary.

\(

\therefore \quad c^2-4 a b<0 \Rightarrow c^2<4 a b

\)

Let \(y=3 b^2 x^2+6 b c x+2 c^2\). Clearly, it represents a parabola opening upward. So,

\(

y_{\min }=-\frac{36 b^2 c^2-24 b^2 c^2}{12 b^2}=-c^2>-4 a b

\)

Example 65: The quadratic equations \(x^2-6 x+a=0\) and \(x^2-c x+6=0\) have one root in common. The other roots of the first and second equations are integers in the ratio \(4: 3\). Then, the common root is [AIEEE 2008]

(a) 3

(b) 2

(c) 1

(d) 4

Solution: (b) Let \(\alpha\) be the common root and other roots be \(4 \beta\) and \(3 \beta\) respectively.

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore \quad \alpha+4 \beta=6 \text { and } 4 \alpha \beta=a & {\left[\begin{array}{r}

\because \alpha, 4 \beta \text { are roots of } \\

x^2-6 x+a=0

\end{array}\right]} \\

\alpha+3 \beta=c \text { and } 3 \alpha \beta=6 & {\left[\begin{array}{r}

\because \alpha, 3 \beta \text { are roots of } \\

x^2-c x+6=0

\end{array}\right]}

\end{array}

\)

Now, \(4 \alpha \beta=a\) and \(3 \alpha \beta=6 \Rightarrow a=8\)

Putting \(a=8\) in \(x^2-6 x+a=0\), we get \(x=2,4\).

If \(\alpha=2\) and \(4 \beta=4\), then \(\beta=1\).

So, roots of the two equations are 2,4 and 2,3.

Clearly, 2 is the common root.

If \(\alpha=4,4 \beta=2\), then \(\beta=\frac{1}{2}\).

In this case, roots of the second equation are not integer.

So, \(\alpha=4,4 \beta=2\) is not possible.

Example 66: The smallest value of \(k\) for which both the roots of the equation \(x^2-8 k x+16\left(k^2-k+1\right)=0\) are real, distinct and have values at least 4 , is [IIT 2009]

(a) 2

(b) 3

(c) 4

(d) none of these

Solution: (a) Let \(f(x)=x^2-8 k x+16\left(k^2-k+1\right)\). Both the roots of the equation \(f(x)=0\) will be real, distinct and have values at least 4, if

(i) \(D>0\)

(ii) \(f(4) \geq 0\)

(iii) Vertex of \(y=f(x)\) lies on the right side of \((4,0)\)

Now,

(i) \(D>0 \Rightarrow 64 k^2-64\left(k^2-k+1\right)>0 \Rightarrow k-1>0 \Rightarrow k>1\)

(ii) \(f(4) \geq 0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}