5.5 Argand Plane and Polar Representation

Argand Plane and Polar Representation

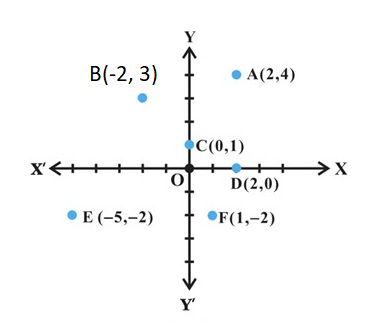

Some complex numbers such as \(2+4 i,-2+3 i, 0+1 i, 2+0 i,-5-2 i\) and \(1-2 i\) which correspond to the ordered pairs \((2,4),(-2,3),(0,1),(2,0),(-5,-2)\), and \((1,-2)\), respectively, have been represented geometrically by the points \(\mathrm{A}, \mathrm{B}, \mathrm{C}, \mathrm{D}, \mathrm{E}\), and \(\mathrm{F}\), respectively in the figure below.

The plane having a complex number assigned to each of its point is called the complex plane or the Argand plane.

Polar representation of a complex number

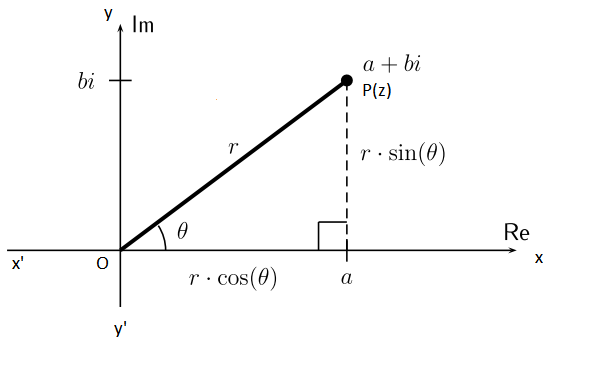

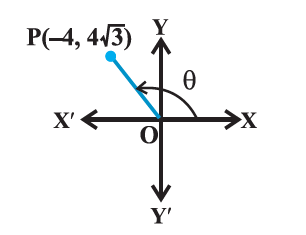

Let the point P represent the non-zero complex number \(z=a+b i\). Let the directed line segment OP be of length \(r\) and \(\theta\) be the angle which OP makes with the positive direction of \(x\)-axis (Fig below). Instead of giving the \(x\) and \(y\) coordinates, we will give a distance \(r\) (the modulus) and angle \(\theta\) (the argument). We call this the polar form of a complex number. We may note that the point \(P\) is uniquely determined by the ordered pair of real numbers \((r, \theta)\), called the polar coordinates of the point \(\mathrm{P}\). We consider the origin as the pole and the positive direction of the \(x\) axis as the initial line.

As shown in the diagram, the coordinates a and b are given by \(a=r \cos \theta, b=r \sin \theta\) and therefore, \(z=r(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)\). The latter is said to be the polar form of the complex number. Here \(r=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}=|z|\) is the modulus of \(z\) and \(\theta\) is called the argument (or amplitude) of \(z\) which is denoted by \(\arg z\).

\(\text { Polar form: } a+b i=r(\cos (\theta)+i \cdot \sin (\theta))\)How do we find the modulus \(r\) and the argument \(\theta\)?

Note that \(r\) is given by the absolute value. For \(\theta\), we note that

\(\frac{b}{a}=\frac{r \cdot \sin (\theta)}{r \cdot \cos (\theta)}=\frac{\sin (\theta)}{\cos (\theta)}=\tan (\theta)\).

This leads to the following:

Formulas for converting to polar form (finding the modulus \(r\) and argument \(\theta): r=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}, \tan (\theta)=\frac{b}{a}\)

Polar Representation of Complex Numbers in different Quadrants

We know that the unique value of \(\theta\) that lies in the range \((-\pi \leq \theta \leq \pi)\) is called the principal argument or principal value of the amplitude. The point to be remembered is the value of the principal argument of a complex number (z) depends on the position of the complex number (z) i.e the quadrant in which the complex number ( \(z\) ) lies.

Let’s discuss the different cases to find out the value of the principal argument. Let \(\alpha\) be the acute angle subtended by OP with the \(X\)-axis and \(\theta\) is the principal argument of the complex number \((z)\)

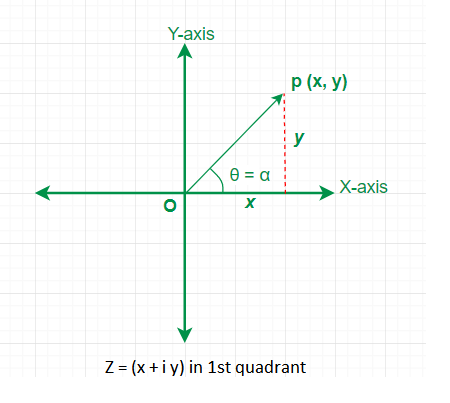

Case-1: When the complex number \(z=x+i y, z\) lies in first quadrant \((x>0\) and \(y>0)\) From the figure below \(\tan \alpha=|y / x|\) and then the value of the principal argument \((\theta=\alpha)\).Then \(\arg (z)=\tan ^{-1}|y / x|\).

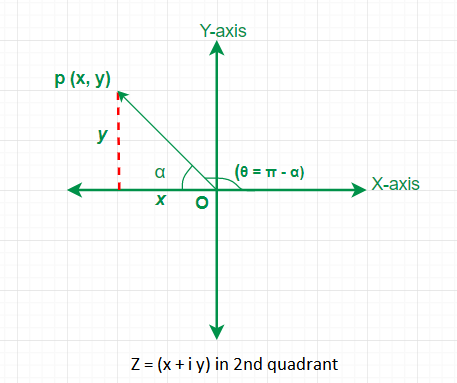

Case 2: \(z=x+i y, z\) lies in second quadrant \((x<0\) and \(y>0)\)

From the figure below \(\tan \alpha=|y / x|\) and then the value of the principal argument \(\theta=\pi-\alpha\).

Then \(\arg (z)=\pi-\alpha\), where \(\alpha\) is the acute angle given by \(\tan ^{-1}|y / x|\).

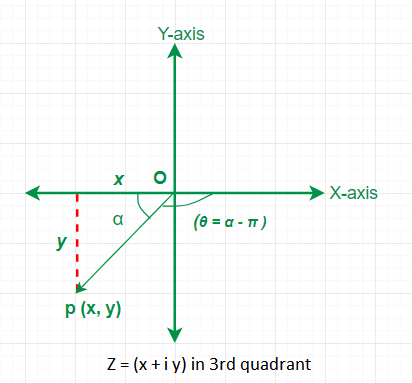

Case 3: \(z=x+i y, z\) lies in third quadrant \((x<0\) and \(y<0)\) From the figure below \(\tan \alpha=|y / x|\) and then the value of the principal argument \(\theta=-(\pi-\alpha)=-\pi+\alpha\). Then, \(\arg (z)=\alpha-\pi\) where \(\alpha\) is the acute angle given by \(\tan \alpha=|y / x|\).

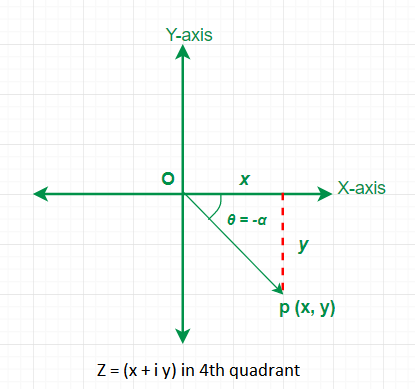

Case 4: \(z=x+i y, z\) lies in fourth quadrant \((x>0\) and \(y<0)\)

From the figure \(\tan \alpha=|y / x|\) and then the value of the principal argument \(\theta=-\alpha\).

Then \(\arg (z)=-\alpha\), where \(\alpha\) is the acute angle given by \(\tan \alpha=|y / x|\).

Polar form of a complex number

We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& z=x+i y \\

& =\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\left[\frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}+i \frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}}\right]=|z|[\cos \theta+i \sin \theta]

\end{aligned}

\)

where \(|z|\) is the modulus of complex number, i.e. the distance of \(z\) from origin and \(\theta\) is the argument or amplitude of the complex number.

Here we should take the principal value of \(\theta\). For general values of argument \(z=r[\cos (2 n \pi+\theta)+i \sin (2 n \pi+\theta)]\) (where \(n\) is an integer). This is polar form of the complex number.

The polar form of a complex number (z) is given by

\(

z=|z| \cos \theta+i|z| \sin \theta

\), Where \(|z|=r\)

\(

z=r(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)

\)

If we take the general value of the argument \(\arg (z)=2 n \pi+\theta\), then the polar form of \(z\) is given by \(z=r[\cos (2 n \pi+\theta)+i \sin (2 n \pi+\theta)]\); where \(n\) is an integer.

As we have \(\theta\) in the expression of the polar form of \(z\) then again there will be four different cases depending upon the principal argument values \(\theta\) in the four quadrants. Let’s discuss them using the results obtained above for the principal argument \(\theta\).

- Case 1: When the complex number \(z\) lies in the first quadrant then the value of the principal argument \((\theta=\alpha)\). So, the polar form of \(z=r(\cos \alpha+i \sin \alpha)\).

- Case 2: When the complex number \(z\) lies in the second quadrant then the value of the principal argument \((\theta=\pi-\alpha)\). So, the polar form of \(z=r[\cos (\pi-\alpha)+i \sin (\pi-\alpha)]\) or \(z=r\) \((-\cos \alpha+i \sin \alpha)\)

- Case 3: When the complex number \(z\) lies in the third quadrant then the value of the principal argument \((\theta=\alpha-\pi)\). So, the polar form of \(z=r[\cos (\alpha-\pi)+i \sin (\alpha-\pi)]\) or \(z=r(-\cos \alpha-i\) \(\sin \alpha)\)

- Case 4: When the complex number \(z\) lies in the fourth quadrant then the value of the principal argument \((\theta=-\alpha)\). So, the polar form of \(z=r[\cos (-\alpha)+i \sin (-\alpha)]\) or \(z=r(\cos \alpha-i\) \(\sin \alpha) .\)

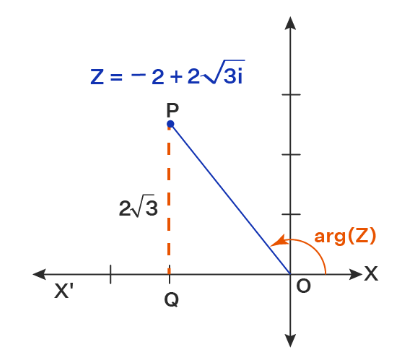

Example 1: For the complex number \(z=-2+2 \sqrt{3} i\),determine its magnitude and argument.

Solution: We know the complex number z lies in the second quadrant as shown in the figure below.

Applying Pythagoras Theorem, the distance of \(z\) from the origin, or the magnitude of \(z\), is \(|z|=\sqrt{ }\left((-2)^2+(2 \sqrt{3})^2\right)=\sqrt{ }(4+12)=\sqrt{16}=4\).

Now, let us calculate the angle between the line segment joining the origin to \(z\) (OP) and the positive real direction (ray OX). Note that the angle POX \({ }^{\prime}\) is \(\tan ^{-}\) \({ }^1(2 \sqrt{3} /(-2))=\tan ^{-1}(-\sqrt{3})=-\tan ^{-1}(\sqrt{ } 3)\).

Since the complex number lies in the second quadrant, the argument \(\theta=-\tan ^{-1}(\sqrt{3})+180^{\circ}=-60^{\circ}+180^{\circ}=\) \(120^{\circ}\).

So, the polar form of complex number \(z=-2+2 \sqrt{3}\) i will be \(4\left(\cos 120^{\circ}+i \sin 120^{\circ}\right)\)

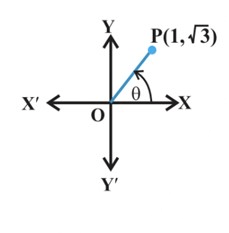

Example 2: Represent the complex number \(z=1+i \sqrt{3}\) in the polar form.

Solution: Let \(1=r \cos \theta, \sqrt{3}=r \sin \theta\)

By squaring and adding, we get

i.e., \(\quad r=\sqrt{4}=2(\) conventionally, \(r>0\) )

Therefore, \(\quad \cos \theta=\frac{1}{2}, \sin \theta=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\), which gives \(\theta=\frac{\pi}{3}\)

Therefore, required polar form is \(z=2\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{3}+i \sin \frac{\pi}{3}\right)\)

The complex number \(z=1+i \sqrt{3}\) is represented as shown in Figure below.

Example 3: Convert the complex number \(\frac{-16}{1+i \sqrt{3}}\) into polar form.

Solution: The given complex number \(\frac{-16}{1+i \sqrt{3}}=\frac{-16}{1+i \sqrt{3}} \times \frac{1-i \sqrt{3}}{1-i \sqrt{3}}\)

\(

=\frac{-16(1-i \sqrt{3})}{1-(i \sqrt{3})^2}=\frac{-16(1-i \sqrt{3})}{1+3}=-4(1-i \sqrt{3})=-4+i 4 \sqrt{3}

\)

Let \(\quad-4=r \cos \theta\), \(4 \sqrt{3}=r \sin \theta\)

By squaring and adding, we get

\(

16+48=r^2\left(\cos ^2 \theta+\sin ^2 \theta\right)

\)

which gives \(r^2=64 \text {, i.e., } r=8\)

Hence \(\cos \theta=-\frac{1}{2}, \sin \theta=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\)

\(

\theta=\pi-\frac{\pi}{3}=\frac{2 \pi}{3}

\)

Thus, the required polar form is \(8\left(\cos \frac{2 \pi}{3}+i \sin \frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)\)

Euler’s Form of Complex Number

\(e^{i \theta}=\cos \theta+i \sin \theta\)

This form makes the study of complex numbers and its properties simple. Any complex number can be expressed as

\(

\begin{aligned}

z & =x+i y \text { (Cartesian form) } \\

& =|z|[\cos \theta+i \sin \theta] \text { (polar form) } \\

& =|z| e^{i \theta}

\end{aligned}

\)

We know,

\(

|z|=r \text { and } \arg (z)=\theta

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Then, }\\

&\begin{aligned}

z & =r(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta) \\

\Rightarrow \quad z & =r e^{i \theta} \quad \text { [Using Euler’s notations] }

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

This form of \(z\) is known as the Eulerian form.

For example, if \(z=1+i\), then \(|z|=\sqrt{2}\) and \(\arg (z)=\pi / 4\)

\(

\therefore \quad z=\sqrt{2} e^{i \pi / 4}

\)

Similarly, we have

\(

-2+2 i=2 \sqrt{2} e^{i 3 \pi / 4} \text { and }-1-i \sqrt{3}=2 e^{i 4 \pi / 3}

\)

Product of Two Complex Numbers

Let two complex numbers be \(z_1=\left|z_1\right| e^{i \theta_1}\) and \(z_2=\left|z_2\right| e^{i \theta_2}\). Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

z_1 z_2 & =\left|z_1\right| e^{i \theta_1} \times\left|z_2\right| e^{i \theta_2} \\

& =\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| e^{i\left(\theta_1+\theta_2\right)} \\

& =\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right|\left[\cos \left(\theta_1+\theta_2\right)+i \sin \left(\theta_1+\theta_2\right)\right]

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left|z_1 z_2\right|=\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right| \\

& \begin{aligned}

\arg \left(z_1 z_2\right) & =\theta_1+\theta_2 \\

& =\arg \left(z_1\right)+\arg \left(z_2\right)

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Division of Two Complex Numbers

\(

\frac{z_1}{z_2}=\frac{\left|z_1\right| e^{i \theta_1}}{\left|z_2\right| e^{i \theta_2}}=\frac{\left|z_1\right|}{\left|z_2\right|} e^{i\left(\theta_1-\theta_2\right)}

\)

\(

\begin{array}{r}

\Rightarrow\left|\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right|=\frac{\left|z_1\right|}{\left|z_2\right|} \\

\text { and } \arg \left(\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right)=\theta_1-\theta_2 \\

\quad=\arg \left(z_1\right)-\arg \left(z_2\right)

\end{array}

\)

Logarithm of a complex number is given by

\(

\begin{aligned}

\log _e(x+i y) & =\log _e\left(|z| e^{i \theta}\right) \\

& =\log _e|z|+\log _e e^{i \theta} \\

& =\log _e|z|+i \theta \\

& =\log _e \sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2\right)}+i \arg (z) \\

\therefore \quad \log _e(z) \quad & =\log _e|z|+i \arg (z)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 4: Write the following complex numbers in polar form: \(\frac{(1+7 i)}{(2-i)^2}\)

Solution: Let \(z=(1+7 i) /\left[(2-i)^2\right]\) Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& z=\frac{1+7 i}{4-4 i+i^2}=\frac{1+7 i}{3-4 i}=\left(\frac{1+7 i}{3-4 i}\right)\left(\frac{3+4 i}{3+4 i}\right)=\frac{-25+25 i}{25}=-1+i \\

& r=|z|=\sqrt{(-1)^2+(1)^2}=\sqrt{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Let \(\alpha\) be the acute angle given by

\(

\tan \alpha=\left|\frac{\operatorname{Im}(z)}{\operatorname{Re}(z)}\right|=\left|-\frac{1}{1}\right|=1

\)

Then \(\alpha=\pi / 4\). Since the point \((-1,1)\) representing \(z\) lies in the second quadrant, therefore \(\theta=\arg (z)=\pi-\alpha=\pi-\pi / 4=3 \pi / 4\). Hence, \(z\) in the polar form is given by

\(

z=\sqrt{2}\left(\cos \frac{3 \pi}{4}+i \sin \frac{3 \pi}{4}\right)

\)

Example 5: If \(z=r e^{i \theta}\), then prove that \(\left|e^{i z}\right|=e^{-r \sin \theta}\).

Solution: \(z=r e^{i \theta}=r(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\Rightarrow \quad & i z=i r(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta) \\

& =-r \sin \theta+i r \cos \theta \\

\Rightarrow \quad & e^{i z}=e^{(-r \sin \theta+i r \cos \theta)} \\

& =e^{-r \sin \theta} e^{r i \cos \theta} \\

\Rightarrow & \left|e^{i z}\right|=\left|e^{-r \sin \theta}\right| e^{r i \cos \theta} \mid \\

& =e^{-r \sin \theta}\left|e^{i \alpha}\right|, \text { where } \alpha=r \cos \theta \\

& =e^{-r \sin \theta}\left[\cos ^2 \alpha+\sin ^2 \alpha\right]^{1 / 2} \\

& =e^{-r \sin \theta}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 6: Prove that

\(

\tan \left(i \log _{\mathrm{e}}\left(\frac{a-i b}{a+i b}\right)\right)=\frac{2 a b}{a^2-b^2}\left(\text { where } a, b \in R^{+}\right)

\)

Solution: Let

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a+i b=r e^{i \theta} \\

\Rightarrow & a-i b=r e^{-i \theta} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{a-i b}{a+i b}=e^{-i 2 \theta} \\

\Rightarrow & \log _e\left(\frac{a-i b}{a+i b}\right)=-i 2 \theta \\

\Rightarrow & \tan \left(i \log _e\left(\frac{a-i b}{a+i b}\right)\right)=\tan 2 \theta \\

= & \frac{2 \tan \theta}{1-\tan ^2 \theta} \\

= & \frac{2 b / a}{1-b^2 / a^2} \\

= & \frac{2 a b}{a^2-b^2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 7: Find the real part of \((1-i)^{-i}\).

Solution: Let \(z=(1-i)^{-i}\). Taking \(\log\) on both sides,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \log z=-i \log _{\mathrm{e}}(1-i) \\

&=-i \log _{\mathrm{e}} \sqrt{2}\left(\cos \frac{\pi}{4}-i \sin \frac{\pi}{4}\right) \\

&=-i \log _{\mathrm{e}}\left(\sqrt{2} e^{-i(\pi / 4)}\right) \\

&=-i\left[\frac{1}{2} \log _e 2+\log _e{ }^{-i \pi / 4}\right] \\

&=-i\left[\frac{1}{2} \log _e 2-\frac{i \pi}{4}\right] \\

&=-\frac{i}{2} \log _e 2-\frac{\pi}{4} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad z=e^{-\pi / 4} e^{-i(\log 2) / 2} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \operatorname{Re}(z)=e^{-\pi / 4} \cos \left(\frac{1}{2} \log 2\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 8: Show that \(e^{2 m i \theta}\left(\frac{i \cot \theta+1}{i \cot \theta-1}\right)^m=1\).

Solution: Let \(\cot ^{-1} p=\theta\). Then \(\cot \theta=p\). Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

\text { L.H.S. } & =e^{2 m i \theta}\left(\frac{i \cot \theta+1}{i \cot \theta-1}\right)^m \\

& =e^{2 m i \theta}\left[\frac{i(\cot \theta-i)}{i(\cot \theta+i)}\right]^m \\

& =e^{2 m i \theta}\left(\frac{\cot \theta-i}{\cot \theta+i}\right)^m

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =e^{2 m i \theta}\left(\frac{\cos \theta-i \sin \theta}{\cos \theta+i \sin \theta}\right)^m \\

& =e^{2 m i \theta}\left(\frac{e^{-i \theta}}{e^{i \theta}}\right)^m \\

& =e^{2 m i \theta}\left(e^{-2 i \theta}\right)^m \\

& =e^{2 m i \theta} e^{-2 m i \theta}=e^0=1=\text { R.H.S. }

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 9: Find the values of \(\theta\) if \((3+2 i \sin \theta) /(1 -2 i \sin \theta\) ) is purely real or purely imaginary.

Solution: \(z=\frac{3+2 i \sin \theta}{1-2 i \sin \theta}\)

Multiplying numerator and denominator by conjugate,

\(

\begin{aligned}

z & =\frac{(3+2 i \sin \theta)(1+2 i \sin \theta)}{1+4 \sin ^2 \theta} \\

& =\frac{3-4 \sin ^2 \theta+8 i \sin \theta}{1+4 \sin ^2 \theta}

\end{aligned}

\)

Now \(z\) is purely real if \(\sin \theta=0\) or \(\theta=n \pi, n \in Z\). \(z\) is purely imaginary if

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 3-4 \sin ^2 \theta=0 \\

\Rightarrow & \sin \theta= \pm \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}= \pm \sin \frac{\pi}{3} \\

\Rightarrow & \theta=n \pi \pm \frac{\pi}{3}, n \in Z

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 10: If \(z\) is a complex number such that \(z^2 =(\bar{z})^2\), then find the location of \(z\) on the Argand plane.

Solution: Let, \(z=x+i y \Rightarrow \bar{z}=x-i y\)

Given that

\(

\begin{aligned}

& z^2=(\bar{z})^2 \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-y^2+2 i x y=x^2-y^2-2 i x y \\

\Rightarrow & 4 i x y=0

\end{aligned}

\)

If \(x \neq 0\), then \(y=0\) and if \(y \neq 0\), then \(x=0\).

Example 11: Consider two complex numbers \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) as \(\alpha=[(a+b i) /(a-b i)]^2+[(a-b i) /(a+b i)]^2\), where \(a, b \in R\) and \(\beta=(z-1) /(z+1)\), where \(|z|=1\), then find the correct statement:

a. both \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are purely real

b. both \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are purely imaginary

c. \(\alpha\) is purely real and \(\beta\) is purely imaginary

d. \(\beta\) is purely real and \(\alpha\) is purely imaginary

Solution: (c) Note that \(\alpha=\bar{\alpha} \Rightarrow \alpha\) is real.

\(

\beta+\bar{\beta}=\frac{z-1}{z+1}+\frac{\bar{z}-1}{\bar{z}+1}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =\frac{(z-1)(\bar{z}+1)+(z+1)(\bar{z}-1)}{(z+1)(\bar{z}+1)} \\

& =\frac{2 z \bar{z}-2}{(z+1)(\bar{z}+1)}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(=0 \quad\left[\right.\) as \(z \bar{z}=|z|^2=1\) (given) \(]\)

Hence the correct statement is (c).

Expressing Complex Numbers in \(\boldsymbol{a}+\boldsymbol{i} \boldsymbol{b}\) Form

The following example illustrates how a complex number can be expressed in the standard \(a+i b\) form.

Solving Complex Equations

Simple equations in \(z\) may be solved by putting \(z=x+i y\) in the equation and equating the real part on the L.H.S. with the real part on the R.H.S. and the imaginary part on the L.H.S. with the imaginary part on the R.H.S.

Example 12: Find the complex number ‘ \(z\) ‘ satisfying \(\operatorname{Re}\left(z^2\right)=0,|z|=\sqrt{3}\).

Solution: \(z=x+i y\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad z^2=x^2-y^2+2 i x y \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \operatorname{Re}\left(z^2\right)=x^2-y^2

\end{aligned}

\)

Also,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& |z|=\sqrt{x^2+y^2} \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-y^2=0, x^2+y^2=3 \\

\Rightarrow & x^2=y^2=\frac{3}{2} \\

\Rightarrow & x= \pm \sqrt{\frac{3}{2}}, y= \pm \sqrt{\frac{3}{2}} \Rightarrow z= \pm \sqrt{\frac{3}{2}} \pm \sqrt{\frac{3}{2}} i

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus there are four complex numbers.

Example 13: Solve the equation \(|z|=z+1+2 i\).

Solution:

\(

|z|=z+1+2 i

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\Rightarrow \sqrt{x^2+y^2} & =x+i y+1+2 i \\

& =x+1+(2+y) i

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \sqrt{x^2+y^2}=x+1 \text { and } 0=2+y \text { or } y=-2 \\

& \Rightarrow \sqrt{x^2+4}=x+1 \\

& \Rightarrow x^2+4=x^2+2 x+1 \\

& \Rightarrow 2 x=3 \\

& \Rightarrow x=3 / 2 \\

& \Rightarrow x+i y=\frac{3}{2}-2 i

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 14: Prove that the triangle formed by the points \(1, \frac{1+i}{\sqrt{2}}\) and \(i\) as vertices in the Argand diagram is isosceles.

Solution: The vertices of the triangle are \(A(1,0), B(1 / \sqrt{2}, 1 / \sqrt{2})\) and \(C(0,1)\),

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \therefore A B^2=(1-1 / \sqrt{2})^2+(0-1 / \sqrt{2})^2=2-\sqrt{2}, B C^2=(1 / \sqrt{2}-0)^2+(1 / \sqrt{2}-1)^2=2-\sqrt{2}, A C^2==(1-0)^2+(0-1)^2=1+1=2 \\

& \therefore A B=B C \Rightarrow \text { Triangle is isosceles }

\end{aligned}

\)

Note: Since \(\boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{B}^2=\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{C}^2\), it follows that \(\boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{B}=\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{C}\). As two sides have equal lengths, the triangle is isosceles.

Example 15: If \((x+i y)^5=p+i q\), then prove that \((y+i x)^5=q+i p\).

Solution: \(\quad(x+i y)^5=p+i q\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \overline{(x+i y)^5}=\overline{p+i q} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad\left(\overline{x+i y)^5}=p-i q\right. \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(x-i y)^5=p-i q \\

& \Rightarrow \quad i^5(x-i y)^5=p i^5-i^6 q \\

& \Rightarrow \quad\left(x i-i^2 y\right)^5=p i+q \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(y+i x)^5=p i+q

\end{aligned}

\)