2.7 JEE Entrance Corner (Relations and Functions)

Ordered Pairs

An ordered pair consists of two objects or elements in a given fixed order.

For example, if \(A\) and \(B\) are any two sets, then by an ordered pair of elements we mean a pair \((a, b)\) in that order, where \(a \in A, b \in B\).

Illustration 1: The position of a point in a two-dimensional plane in Cartesian coordinates is represented by an ordered pair. Accordingly, the ordered pairs \((1,3),(2,4),(2,3)\) and \((3,2)\) represents different points in a \(x-y\) plane.

Equality of Ordered Pairs

Two ordered pairs \(\left(a_1, b_1\right)\) and \(\left(a_2, b_2\right)\) are equal iff \(a_1=a_2\) and \(b_1=b_2\).

i.e. \(\quad\left(a_1, b_1\right)=\left(a_2, b_2\right) \Leftrightarrow a_1=a_2\) and \(b_1=b_2\)

It is evident from this definition that \((1,2) \neq(2,1)\) and \((1,1) \neq(2,2)\).

Illustration 2: Find the values of \(a\) and \(b\), if \((3 a-2, b+3)=(2 a-1,3)\).

Solution: By the definition of equality of ordered pairs, we obtain

\(

(3 a-2, b+3)=(2 a-1,3) \Leftrightarrow 3 a-2=2 a-1 \text { and } b+3=3 \Leftrightarrow a=1 \text { and } b=0

\)

CARTESIAN PRODUCT OF SETS

If \(A\) and \(B\) are any two non-empty sets, then the set of all ordered pairs \((a, b)\) such that \(a \in A\) and \(b \in B\) is called the cartesian product of the set \(A\) with set \(B\) and is denoted by \(A \times B\).

Thus, \(A \times B=\{(a, b): a \in A\) and \(b \in B\}\)

Remarks

- \(A \times B \neq B \times A\) \(\text { and } A \times B=B \times A \Leftrightarrow A=B \text {. }\)

- If \(A\) has \(m\) elements and \(B\) has \(n\) elements, then \(A \times B\) has \(mn\) elements (\(n(A \times B)=m n=n(A) \times n(B)\))

- If \(A=\phi\) and \(B=\phi\), then \(A \times B=\phi\) (null set).

- If either \(A\) or \(B\) is an infinite set, then \(A \times B\) is an infinite set.

- If \(A, B, C\) are finite sets, then \(n(A \times B \times C)=n(A) \times n(B) \times n(C)\)

Example 1: If \(A=\{1,2,3\}\) and \(B=\{4,5\}\), find \(A \times B\), \(B \times A\) and show that \(A \times B \neq B \times A\).

Solution: \(A \times B=\{1,2,3\} \times\{4,5\}=\{(1,4),(1,5),(2,4),(2,5),(3,4)\), \((3,5)\}\)

and \(B \times A=\{4,5\} \times\{1,2,3\}=\{(4,1),(4,2),(4,3),(5,1)\), \((5,2),(5,3)\}\)

It is clear that \(A \times B \neq B \times A\).

Example 2: If \(A=\{1,2,3\}, B=\{3,4,5\}\), then \((A \cap B) \times A\) is

Solution: We have,

\(

\begin{gathered}

A \cap B=\{3\} \text { and } A=\{1,2,3\} \\

(A \cap B) \times A=\{(3,1),(3,2),(3,3)\}

\end{gathered}

\)

Example 3: If \(A\) and \(B\) be two sets and \(A \times B=\{(3,3)\), \((3,4),(5,2),(5,4)\}\), find \(A\) and \(B\).

Solution: \(A=\) First coordinates of all ordered pairs \(=\{3,5\}\) and \(B=\) Second coordinates of all ordered pairs \(=\{2,3,4\}\)

Hence, \(A=\{3,5\}\) and \(B=\{2,3,4\}\)

Example 4: If \(A=\{x \in R: 0<x<1\}\) and \(B=\{y \in R:-1<y<1\}\), then \(A \times B\) is the set of all points lying inside the rectangle having vertices at

Solution: The set \(A\) defines the range for the \(x\)-coordinate.

\(

0<x<1

\)

The set \(\boldsymbol{B}\) defines the range for the \(y\)-coordinate.

\(

-1<y<1

\)

The vertices are formed by combining the extreme values of \(x\) and \(y\).

Vertices are (min \(x, \min y\) ), (min \(x, \max y\) ), (max \(x, \min y\) ), (max \(x, \max y\) ).

Vertices are \((0,-1),(0,1),(1,-1),(1,1)\).

Important Theorems on Cartesian Product

If \(A, B\) and \(C\) are three sets, then

- \(A \times(B \cup C)=(A \times B) \cup(A \times C)\)

- \(A \times(B \cap C)=(A \times B) \cap(A \times C)\)

- \(A \times(B-C)=(A \times B)-(A \times C)\)

- \(A \times B=B \times A \Rightarrow A=B\)

- If \(A \subseteq B\), then \(A \times A \subseteq(A \times B) \cap(B \times A)\) and \(A \times C \subseteq B \times C\) for any set \(C\).

- If \(A \subseteq B\) and \(C \subseteq D\), then \(A \times C \subseteq B \times D\)

- \((A \times B) \cap(C \times D)=(A \cap C) \times(B \cap D)\)

- \((A \times B) \cap(B \times A)=(A \cap B) \times(B \cap A)\)

- \(A \times\left(B^{\prime} \cup C^{\prime}\right)^{\prime}=(A \times B) \cap(A \times C)\)

- \(A \times\left(B^{\prime} \cap C^{\prime}\right)^{\prime}=(A \times B) \cup(A \times C)\)

- If \(A\) and \(B\) have \(n\) elements in common, then \(A \times B\) and \(B \times A\) have \(n^2\) elements in common.

- If \(A \subseteq B\), then \((A \times B) \cap(B \times A)=A^2\)

- \((A \times B) \cap(S \times T)=(A \cap S) \times(B \cap T)\), where \(S\) and \(T\) are two sets.

Example 5: If \(A\) and \(B\) are two sets given in such \(a\) way that \(A \times B\) consists of 6 elements and if three elements of \(A \times B\) are \((1,5),(2,3)\) and \((3,5)\), what are the remaining elements?

Solution: Since, \((1,5),(2,3),(3,5) \in A \times B\), then clearly \(1,2,3 \in A\) and

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 3,5 \in B \\

& \begin{aligned}

A \times B & =\{1,2,3\} \times(3,5) \\

& =(1,3),(1,5),(2,3),(2,5),(3,3),(3,5)

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the remaining elements are \((1,3),(2,5),(3,3)\).

Example 6: If \(A=\{1,2,3\}, B=\{3,4\}\) and \(C=\{1,3,5\}\), find

(i) \(A \times(B \cup C)\)

(ii) \(A \times(B \cap C)\)

(iii) \((A \times B) \cap(A \times C)\)

Solution: (i) Clearly, \(B \cup C=\{1,3,4,5\}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\therefore A \times(B \cup C) & =\{1,2,3\} \times\{1,3,4,5\} \\

& =\{(1,1),(1,3),(1,4),(1,5),(2,1),(2,3),(2,4),(2,5),(3,1),(3,3),(3,4),(3,5)\}

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) Clearly, \(B \cap C=\{3\}\).

\(

\therefore \quad A \times(B \cap C)=\{1,2,3\} \times\{3\}=\{(1,3),(2,3),(3,3)\}

\)

(iii) \(A \times B=\{(1,3),(1,4),(2,3),(2,4),(3,3),(3,4)\}\),

and, \(A \times C=\{(1,1),(1,3),(1,5),(2,1),(2,3),(2,5),(3,1),(3,3),(35)\}\)

\(

\therefore \quad(A \times B) \cap(A \times C)=\{(1,3),(2,3),(3,3)\} .

\)

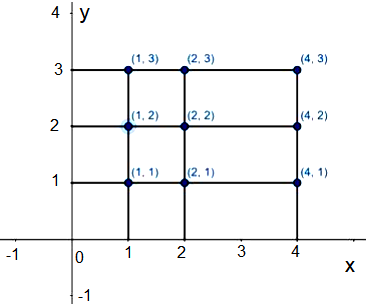

Example 7: If \(A=\{1,2,4\}\) and \(B=\{1,2,3\}\), find \(A \times B\) and show it graphically.

Solution:

\(

A \times B=\{(1,1),(1,2),(1,3),(2,1),(2,2),(2,3),(4,1),(4,2),(4,3)\}

\)

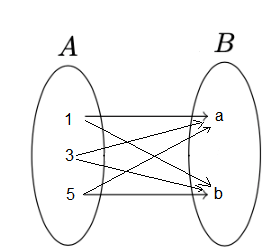

DIAGRAMATIC REPRESENTATION OF CARTESIAN PRODUCT OF TWO SETS

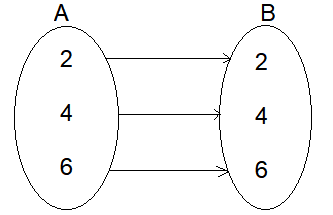

In order to represent \(A \times B\) by an arrow diagram, we first draw Venn diagrams representing sets \(A\) and \(B\) one opposite to the other as shown in the Figure below. Now, we draw line segments starting from each element of \(A\) and terminating to each element of set \(B\).

If \(A=\{1,3,5\}\) and \(B=\{a, b\}\), then the following figure gives the arrow diagram of \(A \times B\).

Relations

Relation is a relationship between two sets. Let \(A\) and \(B\) be two sets. Then, a relation \(R\) from \(A\) to \(B\) is a subset of \(A \times B\).

If \((a, b) \in R\), then we write \(a R b\) which is read as \(a\) is related to \(b\) by the relation \(R\). If \((a, b) \notin R\), then we write \(a \not R b\) and we say that \(a\) is not related to \(b\) by the relation \(R\).

Example 8: If \(A=\{a, b, c, d\}\) and \(B=\{1,2,3\}\), then which of the following is a relation from \(A\) to \(B\)?

(a) \(R_1=\{(a, 1),(2, b),(c, 3)\}\)

(b) \(R_2=\{(a, 1),(d, 3),(b, 2),(b, 3)\}\)

(c) \(R_3=\{(1, a),(2, b),(3, c)\}\)

(d) \(R_4=\{(a, 1),(b, 2),(c, 3),(3, d)\}\)

Solution: (b) is the correct answer.

Explanation: We observe that \((a, 1),(c, 3) \in A \times B\) but \((2, b) \notin A \times B\). So, \(R_1\) is not a relation from \(A\) to \(B\).

Clearly, \(R_2 \subset A \times B\). So, it is a relation from \(A\) to \(B\).

Since \((2, b) \in R_3\) but \((2, b) \notin A \times B\). So, \(R_3 \nsubseteq A \times B\). Hence, it is not a relation from \(A\) to \(B\).

We find that \((3, d) \in R_4\) but \((3, d) \notin A \times B\). So, \(R_4\) is not a relation from \(A\) to \(B\).

Remarks

- If \(A\) and \(B\) are two finite sets consisting of \(m\) and \(n\) elements respectively, then \(A \times B\) consists of \(m n\) ordered pairs. So, the total number of subsets of \(A \times B\) is \(2^{m n}\). Hence, \(2^{m n}\) relations can be defined from \(A\) to \(B\). For example,

Let \(A=\{1,2,3\}\) and \(B=\{4,5\}\), then number of different relations from \(A\) to \(B\) is \(2^{3 \times 2}=2^6=64\) because \(A\) has 3 elements and \(B\) has 2 elements. - Any subset of \(A \times A\) is said to be a relation on \(A\)

REPRESENTATION OF A RELATION

A relation from a set \(A\) to a set \(B\) can be represented in any one of the following forms:

ROSTER FORM: In this form, a relation is represented by the set of all ordered pairs belonging to \(R\).

For example, if \(R\) is a relation from set \(A=\{-2,-1,0,1,2\}\) to set \(B=\{0,1,4,9,10\}\) by the rule \(a R b \Leftrightarrow a^2=b\). Then, \(0 R 0,-2 R 4,-1 R 1,1 R 1\) and \(2 R 4\).

So, \(R\) can be described in Roster form as \(R=\{(0,0),(-1,1),(-2,4),(1,1),(2,4)\}\)

SET-BUILDER FORM: In this form the relation \(R\) from set \(A\) to set \(B\) is represented as \(R=\{(a, b): a \in A, b \in B\) and \(a, b\) satisfy the rule which associates \(a\) and \(b\}\).

For example, if \(A=\{1,2,3,4,5\}, B=\left\{1, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{3}, \frac{1}{4}, \frac{1}{5}, \frac{1}{6}, \ldots\right\}\) and \(R\) is a relation from \(A\) to \(B\) given by \(R=\left\{(1,1),\left(2, \frac{1}{2}\right),\left(3, \frac{1}{3}\right),\left(4, \frac{1}{4}\right),\left(5, \frac{1}{5}\right)\right\}\).

Then, \(R\) in set-builder form can be described as: \(R=\left\{(a, b): a \in A, b \in B\right.\) and \(\left.b=\frac{1}{a}\right\}\).

It should be noted that it is not possible to express every relation from set \(A\) to set \(B\) in set-builder form. For example, the relation \(R=\{(1, a),(1, c),(3, b)\}\) from set \(A=\{1,2,3,4\}\) to set \(B=\{a, b, c\}\) cannot be described in set-builder form.

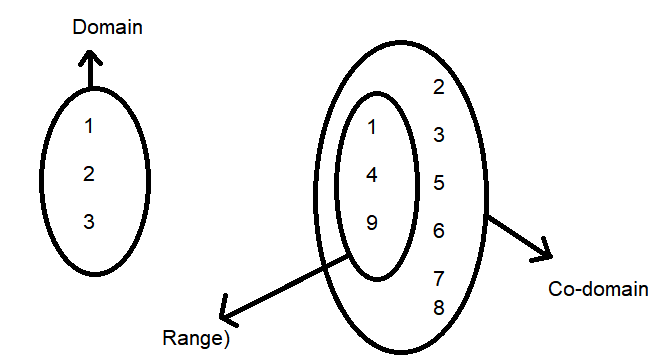

Domain, Co-Domain and Range

Domain

The domain is the set of all possible input values (the ” \(x\) ” values), and the range is the set of all possible output values (the ” \(y\) ” values) in a relation.

For any two non-empty sets \(A\) and \(B\), we define the relation \(R\) as the subset of the Cartesian product of \(A \times B\) where each member of set \(A\) is related to a member of set \(B\) through some unique rule.

We defined relation as,

\(

R=\{(x, y): x \in A \text { and } y \in B\}

\)

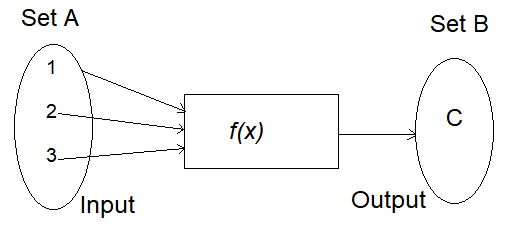

For example, The relation \(R=\{(1,1),(2,4),(3,9)\}\) and it is represented using following diagram:

Range of a Relation

Range of any Relation is the set of output values of the relation. For example, if we take two sets \(A\) and \(B\), and define a relation \(R:\{(a, b): a \in A, b \in B\}\), then the set of values of \(B\) is called the domain of the function.

Codomain of a Relation

We define the codomain of the relation \(R\) as the set \(B\) of the Cartesian product \(A \times B\) on which the relation is defined. Now it is clear that the range of the function is a proper subset of the Codomain.

Range \(\subseteq\) Codomain.

The image given below represents the domain, range and co-domain of a relation.

Illustration: Find the domain and range of the relation \(R:\left\{\left(a, a^2\right) \mid a \in A, a^2 \in A\right\}\) which is defined on \(A \times A\) and the set \(A=\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9\}\).

Solution: Set \(A=\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9\}\)

Relation \(R=\left\{\left(a, a^2\right) \mid a \in A, a^2 \in A\right\}\), defined on \(A \times A\)

If

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a=1: a^2=1 \Rightarrow(1,1) a^2 \in A \\

& a=2: a^2=4 \Rightarrow(2,4) a^2 \in A \\

& a=3: a^2=9 \Rightarrow(3,9) a^2 \in A \\

& a=4: a^2=16 \Rightarrow(4,16) a^2 \notin A

\end{aligned}

\)

Relation \(R\) is defined as,

\(

R=\{(1,1),(2,4),(3,9)\}

\)

Domain of \(R=\{1,2,3\}\)

Range of \(R=\{1,4,9\}\)

Codomain of \(R=\operatorname{Set} A==\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9\}\)

Types of Relations from One Set to Another Set

1. Empty Relation

A relation \(R\) from \(A\) to \(B\) is called an empty relation or a void relation from \(A\) to \(B\) if \(R=\phi\).

For example,

Let \(A=\{2,4,6\}\) and \(B=\{7,11\}\)

Let \(R=\{(a, b): a \in A, b \in B\) and \(a-b\) is even \(\}\)

As, none of the numbers \(2-7,2-11,4-7,4-11\), \(6-7,6-11\) is an even number, \(R=\phi\).

Hence, \(R\) is an empty relation.

2. Universal Relation

A relation \(R\) from \(A\) to \(B\) is said to be the universal relation, if \(R=A \times B\).

For example, Let \(A=\{1,2\}, B=\{1,3\}\) and

\(

R=\{(1,1),(1,3),(2,1),(2,3)\}

\)

Here, \(R=A \times B\)

Hence, \(R\) is the universal relation from \(A\) to \(B\).

Example 9: Let \(A=\{3,5\}, B=\{7,11\}\).

Let \(R=\{(a, b): a \in A, b \in B, a-b\) is even \(\}\).

Show that \(R\) is an universal relation from \(A\) to \(B\).

Solution: Given, \(A=\{3,5\}, B=\{7,11\}\).

Now, \(R=\{(a, b): a \in A, b \in B\) and \(a-b\) is even \(\}\)

\(

=\{(3,7),(3,11),(5,7),(5,11)\}

\)

Also, \(\quad A \times B=\{(3,7),(3,11),(5,7),(5,11)\}\)

Clearly, \(\quad R=A \times B\)

Hence, \(R\) is an universal relation from \(A\) to \(B\).

3. Identity Relation

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is said to be the identity relation on \(A\), if

\(

R=[(a, b): a \in A, b \in A \text { and } a=b]

\)

Thus, identity relation, \(R=[(a, a): \forall a \in A]\)

Identity relation on set \(A\) is also denoted by \(I_A\).

Symbolically, \(I_A=[(a, a): a \in A]\)

For example,

Let \(\quad A=\{1,2,3\}\)

Then, \(I_A=\{(1,1),(2,2),(3,3)\}\)

Example 10: Let \(A=\{1,2,3\}\) and \(R=\{(a, b): a, b \in A, a\) divides \(b\) and \(b\) divides \(a\) }. Show that \(R\) is an identity relation on \(A\).

Solution: Given, \(A=\{1,2,3\}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a \in A, b \in B, a \text { divides } b \text { and } b \text { divides } a . \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a=b \\

& \therefore \quad R=\{(a, a), a \in A\}=\{(1,1),(2,2),(3,3)\}

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, \(R\) is the identity relation on \(A\).

Remark

- In an identity relation on \(A\) every element of \(A\) should be related to itself only.

4. Inverse Relation

If \(R\) is a relation from a set \(A\) to a set \(B\), then inverse relation of \(R\) to be denoted by \(R^{-1}\), is a relation from \(B\) to \(A\).

Symbolically, \(R^{-1}=\{(b, a):(a, b) \in R\}\)

Thus, \(\quad(a, b) \in R \Leftrightarrow(b, a) \in R^{-1}, \forall a \in A, b \in B\).

\begin{aligned}

&\text { For example, }\\

&\begin{aligned}

\text { If } \quad R & =\{(1,2),(3,4),(5,6)\} \text {, then } \\

R^{-1} & =\{(2,1),(4,3),(6,5)\} \\

\therefore\left(R^{-1}\right)^{-1} & =\{(1,2),(3,4),(5,6)\}=R

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Here, \(\operatorname{dom}(R)=\{1,3,5\}\), range \((R)=\{2,4,6\}\)

and \(\operatorname{dom}\left(R^{-1}\right)=\{2,4,6\}\), range \(\left(R^{-1}\right)=\{1,3,5\}\)

Clearly, \(\operatorname{dom}\left(R^{-1}\right)=\operatorname{range}(R)\)

and range \(\left(R^{-1}\right)=\operatorname{dom}(R)\)

Remarks

- Domain \((R)=\) Range \(\left(R^{-1}\right)\) and, Range \((R)=\) Domain \(\left(R^{-1}\right)\).

- \(\left(R^{-1}\right)^{-1}=R\)

Example 11: Let \(A=\{1,2,3, \ldots, 10\}\) and \(R=\{(x, y): x+2 y=10, x, y \in A\}\) be a relation on \(A\). Then, \(R^{-1}=\)

Solution: We have,

\(

(x, y) \in R \Leftrightarrow x+2 y=10 \Leftrightarrow y=\frac{10-x}{2}, \text { where } x, y \in A

\)

We observe that

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=2 \Rightarrow y=4, x=4 \Rightarrow y=3, \\

& x=6 \Rightarrow y=2, x=8, y=1

\end{aligned}

\)

Also, \(x \notin A\) for \(x=1,3,5,7,9,10\).

\(

\therefore \quad R=\{(2,4),(4,3),(6,2),(8,1)\}

\)

Hence, \(R^{-1}=\{(4,2),(3,4),(2,6),(1,8)\}\)

5. Reflexive Relation

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is said to be reflexive, if every element of \(A\) is related to itself. \(R \text { is reflexive } \Leftrightarrow(a, a) \in R \text { for all } a \in A .\)

For example,

Let

\(

\begin{aligned}

A & =\{1,2,3\} \\

R_1 & =\{(1,1),(2,2),(3,3)\} \\

R_2 & =\{(1,1),(2,2),(3,3),(1,2),(2,1),(1,3)\} \\

R_3 & =\{(1,1),(2,2),(2,3),(3,2)\}

\end{aligned}

\)

Here, \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) are reflexive relations on \(A, R_3\) is not a reflexive relation on \(A\) as \((3,3) \notin R_3\), i.e. \(3 R_3 3\).

Remark

- The identity relation is always a reflexive relation but a reflexive relation may or may not be the identity relation. It is clear in the above example given, \(R_1\) is both reflexive and identity relation on \(A\) but \(R_2\) is a reflexive relation on \(A\) but not an identity relation on \(A\)

6. Symmetric Relation

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is said to be a symmetric relation iff

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \quad(a, b) \in R \Rightarrow(b, a) \in R \text { for all } a, b \in A \\

& \text { i.e. } \quad a R b \Rightarrow b R a \text { for all } a, b \in A .

\end{aligned}

\)

It follows from the above definition that a relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is symmetric iff \(R=R^{-1}\). Also, the identity and universal relations on a set \(A\) are always symmetric.

For example,

\(

\text { Let } \quad \begin{aligned}

A & =\{1,2,3\} \\

& R_1=\{(1,2),(2,1)\} \\

& R_2=\{(1,2),(2,1),(1,3),(3,1)\} \\

\text { and } & R_3=\{(2,3),(1,3),(3,1)\}

\end{aligned}

\)

Here, \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) are symmetric relations on \(A\) but \(R_3\) is not a symmetric relation on \(A\) because \((2,3) \in R_3\) and \((3,2) \notin R_3\).

Example 12: Which of the following relations is not symmetric?

(a) \(R_1\) on \(R\) defined by \((x, y) \in R_1 \Leftrightarrow 1+x y>0\) for all \(x, y \in R\)

(b) \(R_2\) on \(N \times N\) defined by \((a, b) R_2(c, d) \Leftrightarrow a+d=b+c\) for all \(a, b, c, d \in N\)

(c) \(R_3\) on \(Z\) defined by \((a, b) \in R_3 \Leftrightarrow b-a\) is an even integer

(d) \(R_4\) on power set of a set \(X\) defined by \(A R_4 B\) iff \(A \subseteq B\).

Solution: Let \((x, y) \in R_1\). Then, \(x, y \in R\) such that

\(

1+x y>0 \Rightarrow 1+y x>0 \Rightarrow(y, x) \in R_1

\)

So, \(R_1\) is a symmetric relation on \(R\).

We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

(a, b) R_2(c, d) & \Leftrightarrow a+d=b+c \\

& \Leftrightarrow c+b=d+a \Leftrightarrow(c, d) R_2(a, b)

\end{aligned}

\)

\(\therefore \quad R_2\) is a symmetric relation on \(N \times N\).

Let \((a, b) \in R_3\). Then,

\(b-a\) is an even integer

\(\Rightarrow \quad a-b\) is an even integer

\(\Rightarrow \quad(b, a) \in R_3\)

\(\therefore \quad R_3\) is a symmetric relation on Z.

Let \(A, B \in P(X)\) such that \(A R_4 B\). Then, \(A \subseteq B\)

This need not imply that \(B \subseteq A\).

So, \(R_4\) is not a symmetric relation on \(P(X)\).

Example 13: Prove that the relation \(R\) defined on the set \(N\) of natural numbers by \(x R y \Leftrightarrow 2 x^2-3 x y+y^2=0\) is not symmetric but it is reflexive.

Solution:

(i) \(2 x^2-3 x \cdot x+x^2=0, \forall x \in N\).

\(\therefore x R x, \forall x \in N\), i.e. \(R\) is reflexive.

(ii) For \(x=1, y=2,2 x^2-3 x y+y^2=0\)

\(

\therefore 1 R 2

\)

But \(2 \cdot 2^2-3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1+1^2=3 \neq 0\)

So, 2 is not related to 1 i.e., \(2 \not R_1\)

\(\therefore R\) is not symmetric.

7. Anti-symmetric Relation

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is said to be anti-symmetric, if \(a R b, b R a \Rightarrow a=b, \forall a, b \in A\)

i.e., \((a, b) \in R\) and \((b, a) \in R \Rightarrow a=b, \forall a, b \in A\)

Example 14: Which of these are antisymmetric?

(i) \(R=\{(1,1),(1,2),(2,1),(2,2),(3,4),(4,1),(4,4)\}\)

(ii) \(R=\{(1,1),(1,3),(3,1)\}\)

(iii) \(R=\{(1,1),(1,2),(1,4),(2,1),(2,2),(3,3),(4,1),(4,4)\}\)

Solution:

(i) \(R\) is not antisymmetric here because of \((1,2) \in R\) and \((2,1) \in R\), but \(1 \neq 2\).

(ii) \(R\) is not antisymmetric here because of \((1,3) \in R\) and \((3,1) \in R\), but \(1 \neq 3\).

(iii) \(R\) is not antisymmetric here because of \((1,2) \in R\) and \((2,1) \in R\), but \(1 \neq 2\) and also \((1,4) \in R\) and \((4,1) \in R\) but \(1 \neq 4\).

Note: A relation that is not antisymmetric is symmetric.

8. Transitive Relation

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is said to be a transitive relation, if \(a R b\) and \(b R c \Rightarrow a R c, \forall a, b, c \in A\)

i.e., \(\quad(a, b) \in R\) and \((b, c) \in R \Rightarrow(a, c) \in R, \forall a, b, c \in A\)

For example,

Let

\(

\begin{aligned}

A & =\{1,2,3\} \\

R_1 & =\{(1,2),(2,3),(1,3),(3,2)\} \\

R_2 & =\{(2,3),(3,1)\} \\

R_3 & =\{(1,3),(3,2),(1,2)\}

\end{aligned}

\)

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is transitive if for all \(a, b, c \in A\), if \((a, b) \in R\) and \((b, c) \in R\), then \((a, c) \in R\).

Check transitivity for \(\boldsymbol{R}_{\mathbf{1}}\):

Given \((2,3) \in R_1\) and \((3,2) \in R_1\).

For transitivity, \((2,2)\) must be in \(R_{\mathbf{I}}\).

Since \((2,2) \notin R_1, R_1\) is not transitive.

Check transitivity for \(\boldsymbol{R}_2\):

Given \((2,3) \in R_2\) and \((3,1) \in R_2\).

For transitivity, \((2,1)\) must be in \(\boldsymbol{R}_2\).

Since \((2,1) \notin R_2, R_2\) is not transitive.

Check transitivity for \(\boldsymbol{R}_3\):

Consider pairs \((a, b) \in R_3\) and \((b, c) \in R_3\).

If \((1,3) \in R_3\) and \((3,2) \in R_3\), then \((1,2)\) must be in \(R_3\), which it is.

No other pairs \((a, b)\) and \((b, c)\) exist where \(b\) is common.

Thus, \(R_3\) is transitive.

\(R_1\) is not transitive, \(R_2\) is not transitive, and \(R_3\) is transitive.

Example 15: Let \(N\) be the set of natural numbers and relation \(R\) on \(N\) be defined by \(x R y \Leftrightarrow x\) divides \(y\), \(\forall x, y \in N\).

Examine whether \(R\) is reflexive, symmetric, anti-symmetric or transitive.

Solution:The set is \(N\), the set of natural numbers.

The relation \(\boldsymbol{R}\) is defined as \(x \boldsymbol{R} y \Leftrightarrow x\) divides \(y\).

How to solve?

We need to check each property (reflexivity, symmetry, anti-symmetry, transitivity) based on the definition of the relation.

Check for Reflexivity:

A relation \(R\) is reflexive if \(x R x\) for all \(x \in N\).

For any natural number \(x, x\) divides \(x\).

So, \(x R x\) holds for all \(x \in N\).

Therefore, \(R\) is reflexive.

Check for Symmetry:

A relation \(R\) is symmetric if \(x R y \Rightarrow y R x\) for all \(x, y \in N\).

Consider \(x=2\) and \(y=4\).

2 divides 4 , so \(2 R 4\).

However, 4 does not divide 2.

So, \(4 R 2\) does not hold.

Therefore, \(R\) is not symmetric.

Check for Anti-symmetry:

A relation \(R\) is anti-symmetric if \(x R y\) and \(y R x \Rightarrow x=y\) for all \(x, y \in N\). If \(x\) divides \(y\) and \(y\) divides \(x\), then \(x=y\) must be true for natural numbers. For example, if \(x=3\) and \(y=3\), then 3 divides 3 and 3 divides 3 , so \(3=3\). Therefore, \(R\) is anti-symmetric.

Check for Transitivity:

A relation \(R\) is transitive if \(x R y\) and \(y R z \Rightarrow x R z\) for all \(x, y, z \in N\).

If \(x\) divides \(y\) and \(y\) divides \(z\), then \(x\) must divide \(z\).

For example, if \(x=2, y=4, z=8\).

2 divides \(4(2 R 4)\) and 4 divides \(8(4 R 8)\).

Also, 2 divides \(8(2 R 8)\).

Therefore, \(R\) is transitive.

The relation \(R\) is reflexive, anti-symmetric, and transitive, but not symmetric.

9. Equivalence Relation

A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is said to be an equivalence relation on \(A\), when \(R\) is (i) reflexive (ii) symmetric and (iii) transitive. The equivalence relation denoted by \(\sim\).

- It is reflexive i.e. \((a, a) \in R\) for all \(a \in A\)

- It is symmetric i.e. \((a, b) \in R \Rightarrow(b, a) \in R\) for all \(a, b \in A\)

- It is transitive i.e. \((a, b) \in R\) and \((b, c) \in R \Rightarrow(a, c) \in R\) for all \(a, b, c \in A\).

Example 16: \(N\) is the set of natural numbers. The relation \(R\) is defined on \(N \times N\) as follows

\(

(a, b) R(c, d) \Leftrightarrow a+d=b+c

\)

Prove that \(R\) is an equivalence relation.

Solution: (i) \((a, b) R(a, b) \Rightarrow a+b=b+a\)

\(\therefore R\) is reflexive.

(ii)

\(

\begin{aligned}

(a, b) R(c, d) \Rightarrow a+d & =b+c \\

\Rightarrow \quad c+b & =d+a \Rightarrow(c, d) R(a, b)

\end{aligned}

\)

\(\therefore R\) is symmetric.

(iii)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (a, b) R(c, d) \text { and }(c, d) R(e, f) \Rightarrow a+d=b+c \\

& \text { and } \quad c+f=d+e \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a+d+c+f=b+c+d+e \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a+f=b+e \Rightarrow(a, b) R(e, f)

\end{aligned}

\)

\(\therefore R\) is transitive.

Thus, \(R\) is an equivalence relation on \(N \times N\).

Example 17:Which one of the following is not an equivalence relation?

(a) \(R_1\) on \(Z\) defined by a \(R_1 b \Leftrightarrow a-b\) is divisible by \(m\), where \(m\) is a fixed positive integer

(b) \(R_2\) on \(R\) defined by a \(R_2 b \Leftrightarrow 1+a b>0\) for all \(a, b \in R\)

(c) \(R_3\) on \(N \times N\) defined by \((a, b) R_3(c, d) \Leftrightarrow a d=b c\) for all \(a, b, c, d \in N\)

(d) \(R_4\) on \(Z\) defined by \(a R_4 b \Leftrightarrow a-b\) is an even integer for all \(a, b \in Z\)

Solution: We observe that \(\left(1, \frac{1}{2}\right) \in R_2\) and \(\left(\frac{1}{2},-1\right) \in R_2\) but \((1,-1) \notin R_2\). So, \(R_2\) is not a transitive relation. Hence, it is not an equivalence relation.

It can be easily checked that \(R_1, R_3\) and \(R_4\) are equivalence relations.

Explanation: An equivalence relation must be reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.

Reflexive: \(a R a\).

Symmetric: If \(a R b\), then \(b R a\).

Transitive: If \(a R b\) and \(b R c\), then \(a R c\).

How to solve?

Check each relation for reflexivity, symmetry, and transitivity to find the one that fails at least one property.

Check \(R_1\) for equivalence properties:

Reflexive: \(a-a=0\), which is divisible by \(m\). So, \(a R_1 a\).

Symmetric: If \(a-b\) is divisible by \(m\), then \(b-a=-(a-b)\) is also divisible by \(m\). So, \(b R_1 a\).

Transitive: If \(a-b\) and \(b-c\) are divisible by \(m\), then \((a-b)+(b-c)=a-c\) is divisible by \(m\). So, \(a R_1 c\).

\(R_1\) is an equivalence relation.

Check \(R_2\) for equivalence properties:

Reflexive: \(1+a \cdot a=1+a^2>0\) for all \(a \in R\). So, \(a R_2 a\).

Symmetric: If \(1+a b>0\), then \(1+b a>0\). So, \(b R_2 a\).

Transitive: Consider \(a=1, b=-0.5, c=-3\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 1+a b=1+(1)(-0.5)=0.5>0, \text { so } a R_2 b \\

& 1+b c=1+(-0.5)(-3)=1+1.5=2.5>0, \text { so } b R_2 c \\

& 1+a c=1+(1)(-3)=-2<0, \text { so } a R_2 c \text { is false. }

\end{aligned}

\)

\(R_2\) is not transitive, thus not an equivalence relation.

Check \(R_3\) for equivalence properties:

Reflexive: \((a, b) R_3(a, b) \Leftrightarrow a b=b a\), which is true.

Symmetric: If \((a, b) \boldsymbol{R}_3(c, d) \Leftrightarrow a d=b c\), then \((c, d) \boldsymbol{R}_3(a, b) \Leftrightarrow c b=d a\), which is equivalent.

Transitive: If \((a, b) \boldsymbol{R}_3(c, d)\) and \((c, d) \boldsymbol{R}_3(e, f)\), then \(a d=b c\) and \(c f=d e\).

Multiply equations: \(a d c f=b c d e\).

Since \(c, d \in N, c \neq 0, d \neq 0\), so \(a f=b e\).

Thus, \((a, b) R_3(e, f)\).

\(R_3\) is an equivalence relation.

Check \(\boldsymbol{R}_4\) for equivalence properties:

Reflexive: \(a-a=0\), which is an even integer. So, \(a R_4 a\).

Symmetric: If \(a-b\) is even, then \(b-a=-(a-b)\) is also even. So, \(b R_4 a\).

Transitive: If \(a-b\) and \(b-c\) are even, then \((a-b)+(b-c)=a-c\) is even. So, \(a R_4 c\). \(R_4\) is an equivalence relation.

The relation \(R_2\) is not an equivalence relation because it is not transitive.

SOME USEFUL RESULTS ON EQUIVALENCE RELATIONS

Following are some useful results on relations.

- The intersection of two equivalence relations on a set is an equivalence relation on the set.

- The union of two equivalence relations on a set is not necessarily an equivalence relation on the set.

- The inverse of an equivalence relation on a set is also an equivalence relation on the set.

- A relation \(R\) on a set \(A\) is symmetric iff \(R=R^{-1}\).

10. COMPOSITION OF RELATIONS

A composition of relations is a method whereby two sets are combined to produce a new one by use of a combination of every feasible pair of elements from the two sets, so indirectly.

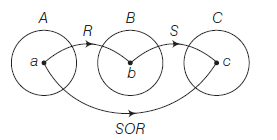

For example, let us consider that we have three sets: \(A, B\), and \(C\). Let \(R\) be a relation from \(A\) to \(B\) and let \(S\) be a relation from \(B\) to \(C\). The composition \(S o R\) is a relation from \(A\) to \(C\) that contains all pairs \((a, c)\) such as there is an element \({b} \in {B}\) such that \(({a}, {b}) \in R\) and \(({b}, {c}) \in S\).

For Example, Suppose, we have three sets namely, \(A=\{1,2\}, B=\{3,4\}\), and \(C=\{5,6\}\), with \(R= \{(1,3),(2,4)\}\), and \(S=\{(3,5),(4,6)\}\). Then the composition \(S o R\) would be \(\{(1\), \(5),(2,6)\), because 1 is linked to 5 through 3 and 2 is linked to 6 through 4.

For example, if \(A=\{1,2,3\}, B=\{a, b, c, d\}, C=\langle p, q, r, s\rangle\) be three sets such that \(R=\{(1, a),(2, c),(1, c),(2, d)\}\) is a relation from \(A\) to \(B\) and \(S=\{(a, s),(b, q),(c, r)\}\) is relation from \(B\) to \(C\). Then, \(SoR\) is a relation from \(A\) to \(C\) given by

\(

S o R=\{(1, s)(2, r)(1, r)\}

\)

In this case, \(R o S\) does not exist.

Explanation: Given,

Set \(A=\{1,2,3\}\).

Set \(B=\{a, b, c, d\}\).

Set \(C=\{p, q, r, s\}\).

Relation \(R=\{(1, a),(2, c),(1, c),(2, d)\}\) is from \(A\) to \(B\).

Relation \(S=\{(a, s),(b, q),(c, r)\}\) is from \(B\) to \(C\).

Find pairs \((x, z)\) such that there exists a \(y \in B\) where \((x, y) \in R\) and \((y, z) \in S\).

Identify elements in \(R\) and \(S\) that can be chained:

For each \((x, y) \in R\), check if there is a \((y, z) \in S\).

Form the composite relation SoR:

If \((x, y) \in R\) and \((y, z) \in S\), then \((x, z) \in S o R\).

For \((1, a) \in R\) and \((a, s) \in S\), we get \((1, s) \in S o R\).

For \((2, c) \in R\) and \((c, r) \in S\), we get \((2, r) \in S o R\).

For \((1, c) \in R\) and \((c, r) \in S\), we get \((1, r) \in S o R\).

For \((2, d) \in R\), there is no pair in \(S\) starting with \(d\).

The composite relation \(S o R\) is given by \(\{(1, s),(2, r),(1, r)\}\).

Example 18: Given the two relations as below:

Relation ( \(R\) ) is given as: \(\{(1,2),(2,3)\}\)

Relation (\(S\)) is given as: \(\{(2,1),(3,2)\}\)

Find \(S o R\) and \(R o S\).

Solution: Now, let us consider that \((a, b) \in R\), and we need to find the corresponding \(b\) in \(S\) as ( \(b, c\) ) in order to form the composition of relations.

And finally after combining the pairs we can get \(S o R\) where \((a, c) \in(S o R\) ). Now, from the given relations:

Now if we combine \((1,2)\) from \(R\) and \((2,1)\) from \(S\) it is going to result of \((1,1)\).

We can merge \((2,3)\) from \(R\) and \((3,2)\) from \(S\) to get \((2,2)\).

Therefore, we obtain \(S o R=\{(1,1),(2,2)\}\).

Now, let us consider that \((a, b) \in S\), and we need to find the corresponding \(b\) in \(R\) as ( \(b, c\) ) in order to form the composition of relations.

And finally after combining the pairs we can get \(R o S\) where \((a, c) \in(R o S\)). Now, from the given relations:

Now if we combine \((2,1)\) from \(R\) and \((1,2)\) from \(S\) it is going to result of \((2,2)\).

We can merge \((3,2)\) from \(R\) and \((2,3)\) from \(S\) to get \((3,3)\).

Therefore, we obtain \(R o S=\{(2,2),(3,3)\}\).

Note: In general, we have \(R o S \neq S o R\). Also, \((S o R)^{-1}=R^{-1} o S^{-1}\).

For example, If \(A, B\) and \(C\) are three sets such that \(R \subseteq A \times B\) and \(S \subseteq B \times C\), then \((S O R)^{-1}=R^{-1} O S^{-1}\). It is clear that \(a R b, b S c\) \(\Rightarrow a S O R c\).

\begin{aligned}

&\text { More generally, }\\

&\left(R_1 O R_2 O R_3 O \ldots O R_n\right)^{-1}=R_n^{-1} O \ldots O R_3^{-1} O R_2^{-1} O R_1^{-1} \\

\end{aligned}

\)

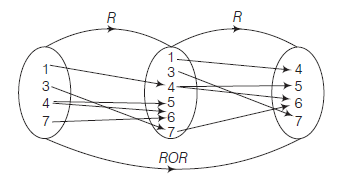

Example 19: Let \(R\) be a relation such that \(R=\{(1,4),(3,7),(4,5),(4,6),(7,6)\}\), find

(i) \(R^{-1} O R^{-1}\) and

(ii) \(\left(R^{-1} O R\right)^{-1}\).

Solution: (i) We know that, \((R O R)^{-1}=R^{-1} O R^{-1}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \operatorname{Dom}(R)=\{1,3,4,7\} \\

& \operatorname{Range}(R)=\{4,5,6,7\}

\end{aligned}

\)

We know that,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 1 \longrightarrow 4 \longrightarrow 5 \Rightarrow(1,5) \in R O R \\

& 1 \longrightarrow 4 \longrightarrow 6 \Rightarrow(1,6) \in R O R \\

& 3 \longrightarrow 7 \longrightarrow 6 \Rightarrow(3,6) \in R O R

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\therefore \quad R O R & =\{(1,5),(1,6),(3,6)\} \\

\text { Then, } R^{-1} O R^{-1} & =(R O R)^{-1} \\

& =\{(5,1),(6,1),(6,3)\}

\end{aligned}

\)

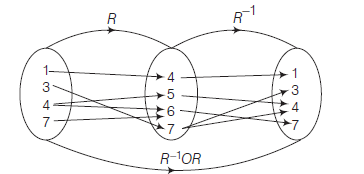

(ii) We know that, \(\left(R^{-1} O R\right)^{-1}=R^{-1} O\left(R^{-1}\right)^{-1}=R^{-1} O R\) Since,

\(

\begin{aligned}

R & =\{(1,4),(3,7),(4,5),(4,6),(7,6)\} \\

\therefore \quad R^{-1} & =\{(4,1),(7,3),(5,4),(6,4),(6,7)\} \\

\therefore \operatorname{Dom}(R) & =\{1,3,4,7\}, \text { Range }(R)=\{4,5,6,7\}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\operatorname{Dom}\left(R^{-1}\right)=\{4,5,6,7\}, \operatorname{Range}\left(R^{-1}\right)=\{1,3,4,7\}

\)

We se that,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 1 \xrightarrow{R} 4 \xrightarrow{R^{-1}} 1 \Rightarrow(1,1) \in R^{-1} O R \\

& 3 \xrightarrow{R} 7 \xrightarrow{R^{-1}} 3 \Rightarrow(3,3) \in R^{-1} O R \\

& 4 \xrightarrow{R} 5 \xrightarrow{R^{-1}} 4 \Rightarrow(4,4) \in R^{-1} O R \\

& 4 \xrightarrow{R} 6 \xrightarrow{R^{-1}} 4 \Rightarrow(4,4) \in R^{-1} O R

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 4 \xrightarrow{R} 6 \xrightarrow{R^{-1}} 7 \Rightarrow(4,7) \in R^{-1} O R \\

& 7 \xrightarrow{R} 6 \xrightarrow{R^{-1}} 4 \Rightarrow(7,4) \in R^{-1} O R \\

& 7 \xrightarrow{R} 6 \xrightarrow{R^{-1}} 7 \Rightarrow(7,7) \in R^{-1} O R

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\therefore R^{-1} O R=\{(1,1),(3,3),(4,4),(7,7),(4,7),(7,4)\}\\

&\text { Hence, }\left(R^{-1} O R\right)^{-1}=R^{-1} O R=\{(1,1),(3,3)\\

&(4,4),(7,7),(4,7),(7,4)\}

\end{aligned}

\)

Theorems on Binary Relations: If \(R\) is a relation on a set \(A\), then

- \(R\) is reflexive \(\Rightarrow R^{-1}\) is reflexive.

- \(R\) is symmetric \(\Rightarrow R^{-1}\) is symmetric.

- \(R\) is transitive \(\Rightarrow R^{-1}\) is transitive.

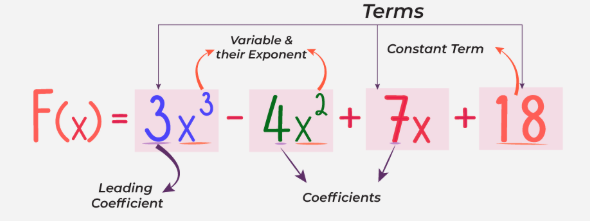

Functions

Introduction

Roughly speaking, term function is used to define the dependence of one physical quantity on another e.g., volume \(V\) of a sphere of radius \(r\) is given by \(V=\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3\). This dependence of \(V\) on \(r\) would be denoted as \(V=f(r)\) and we would simply say that \(V\) is a function of \(r\). Here \(f\) is purely a symbol (for that matter, any other letter could have been used in place of \(f\) ), and it is simply used to represent the dependence of one quantity on the other.

If two variable quantities \(x\) and \(y\) are so related that corresponding to each value of \(x\) (considered only real), which belongs to set \(A\), there corresponds one and only one finite value of the quantity \(y\) (i.e., unique value of \(y\) ). Then, \(y\) is said to be a function (single valued) of \(x\), defined by \(y=f(x)\), where \(x\) is the argument or independent variable and \(y\) is the dependent variable defined on the set \(A\).

For example, If \(r\) is the radius of the circle and \(A\) its area, then \(r\) and \(A\) are related by \(A=\pi r^2\) or \(A=f(r)\). Then, we say that the area \(A\) of the circle is the function of the radius \(r\). Graphically,

Where, \(y\) is the image of \(x\) and \(x\) is the pre-image of \(y\) under \(f\).

Remark

- If to each value of \(x\), which belongs to set \(A\) there corresponds one or more than one values of the quantity \(y\). Then, \(y\) is called the multiple valued function of \(x\) defined on the set \(A\).

- The word ‘FUNCTION’ is used only for single valued function. For example, \(y=\sqrt{x}\) is single valued functions but \(y^2=x\) is a multiple valued function.

\(\therefore \quad y^2=x \Rightarrow y= \pm \sqrt{x}\) for one value of \(x, y\) gives two values.

Definition of Functions

Function can be easily defined with the help of the concept of mapping.

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be any two non-empty sets. “then a function from \(A\) to \(B\) is a correspondence that assigns to each element of \(x\) in set \(A\), one and only one element of set \(B\) “. Let the correspondence be \(f\).

Then mathematically we write \(f: A \rightarrow B\) (which is read as \(f\) is a mapping from \(A\) to \(B\).) where \(y=f(x), x \in A\) and \(y \in B\). We say that \(y\) is the image of \(x\) under \(f\) (or \(x\) is the pre-image of \(y\) ).

The other terms used for functions are operators or transformations.

Remark

- If \(x \in A, y=[f(x)] \in B\), then \((x, y) \in f\).

- If \(\left(x_1, y_1\right) \in f\) and \(\left(x_2, y_2\right) \in f\), then \(y_1=y_2\).

One-one and Many-one Mapping

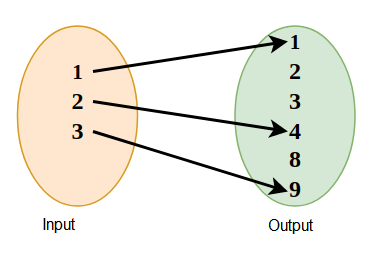

The mapping \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is said to be a function if each element in the set \(A\) has a image in set \(B\). It is possible that a few elements in the set \(B\) are present which are not the images of any element in set \(A\).

Every element in set \(A\) should have one and only one image. That means it is impossible to have more than one image for a specific element in set \(A\). Functions cannot be multi-valued (A mapping that is multi-valued is called a relation from \(A\) and \(B\) ).

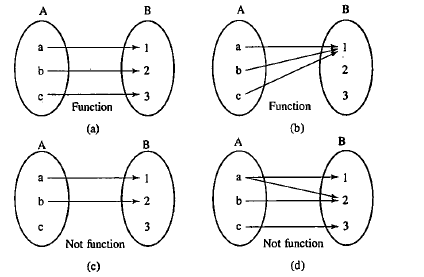

Figure below shows which are functions and which are not.

One-one Mapping

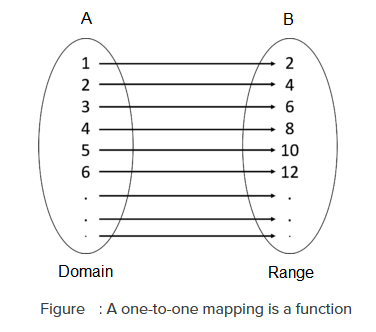

\(f: A \rightarrow B\) is called one-one mapping, if no two different elements of \(A\) have the same image in \(B\). A one-to-one mapping means every element in the domain (input) is mapped to exactly one element in the range (output), and every element in the range is mapped by only one element in the domain (shown in figure below).

Many-one Mapping

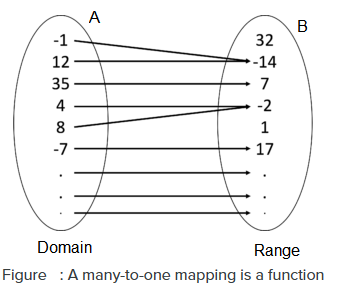

The mapping \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is called many-one mapping, if two or more than two different elements in \(A\) have the same image in \(B\) (as shown in Figure below).

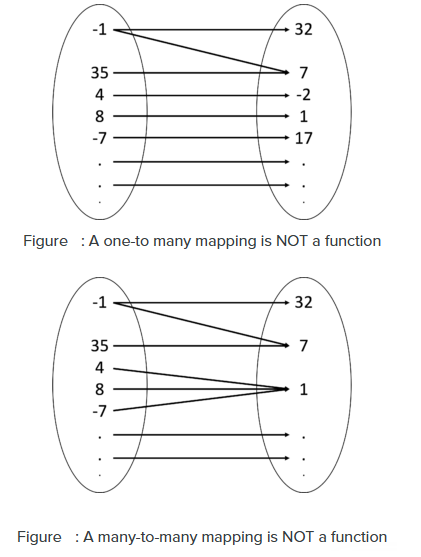

One-to-many and many-to-many mappings are not functions

A one-to-many mapping means, there is at least one element in the domain that is mapped to two or more elements in the range (See Figure below). A many-to-many mapping means there are many-to-one and one-to-many cases in the mapping (See Figure below).

Remarks

- For each value in the domain, there is one and only one corresponding value in the range.

- Every element in the domain must be mapped to one and only one corresponding element in the range.

- Every function is a relation but every relation is not necessarily a function.

ONE-ONE FUNCTION (injective function)

If each element in the domain of a function has a distinct image in the co-domain, the function is said to be one-one. One-one functions are also called injective functions.

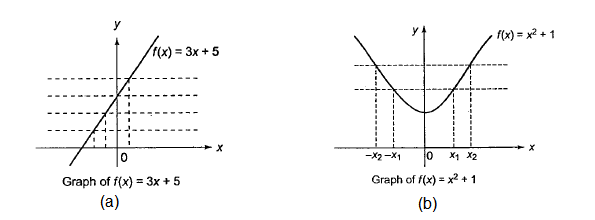

For example, \(f: R \rightarrow R\) given by \(f(x)=3 x+5\) is one-one.

On the other hand, if there are at least two elements in the domain whose images are the same, the function is known as many-one.

For example, \(f: R \rightarrow R\) given by \(f(x)=x^2+1\) is many-one.

Note: A function will be either one-one or many-one.

A function ‘ \(f\) ‘ from a set ‘ \(A\) ‘ to a set ‘ \(B\) ‘ is one-to-one if no two elements in ‘ \(A\) ‘ are mapped to the same element in ‘\(B\).’ Thus,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& f: A \rightarrow B \text { is one-one } \\

\Leftrightarrow & f(a)=f(b) \Rightarrow a=b \text { for all } a, b \in A

\end{array}

\)

If \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is not one-one, then it is said to be a many-one function.

Example 20: A mapping \(f: X \rightarrow Y\) is one-one, if

(a) \(f\left(x_1\right) \neq f\left(x_2\right)\) for all \(x_1, x_2 \in X\)

(b) \(f\left(x_1\right)=f\left(x_2\right) \Rightarrow x_1=x_2 \quad\) for all \(x_1, x_2 \in \mathrm{X}\)

(c) \(\quad x_1=x_2 \quad \Rightarrow f\left(x_1\right)=f\left(x_2\right) \quad\) for all \(x_1, x_2 \in X\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) is the correct option.

Explanation: (a) \(f\left(x_1\right) \neq f\left(x_2\right)\) for all \(x_1, x_2 \in X\) :

This condition states that if \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) are different, their images under \(f\) must be different. While this is a necessary condition for a function to be one-to-one, it’s not sufficient. It is not necessary for every distinct input to have a different output. For example: \(f(x)=x^2\) is not one to one because \(f(2)=f(-2)=4\).

(b) \(f\left(x_1\right)=f\left(x_2\right) \Rightarrow x_1=x_2\) for all \(x_1, x_2 \in X\) :

This is the definition of a one-to-one function. It states that if the images of two elements are the same, then the elements themselves must be the same. This is a formal way of saying that each output has only one possible input.

(c) \(x_1=x_2 \Rightarrow f\left(x_1\right)=f\left(x_2\right)\) for all \(x_1, x_2 \in X\) :

This condition is simply stating that the function is well-defined. It essentially means that for a given input, there is only one possible output. This condition is true for any function, not just one-to-one functions.

METHODS OF CHECKING INJECTIVITY OF A FUNCTION

Algebraic Method:

Following steps may be used to check the injectivity of a function \(f\) :

- Step 1: Take two arbitrary elements \(x, y\) (say) in the domain of \(f\).

- Step 2: Put \(f(x)=f(y)\) and simplify it. If it gives \(x=y\) only, then \(f\) is one-one otherwise it is a many-one function.

Example 21: Which one of the following functions is one-one?

(a) \(f: R \rightarrow R\) given by \(f(x)=2 x^2+1\) for all \(x \in R\)

(b) \(g: Z \rightarrow Z\) given by \(g(x)=x^4\) for all \(x \in Z\)

(c) \(h: R \rightarrow R\) given \(h(x)=x^3+4\) for all \(x \in R\)

(d) \(\phi: C \rightarrow C\) given by \(\phi(z)=z^3+4\) for all \(z \in C\)

Solution: (c)

We observe that \(f(1)=3\) and \(f(-1)=3\).

\(

\therefore \quad 1 \neq-1 \text { but } f(1)=f(-1)

\)

So, \(f\) is not a one-one function.

Clearly, \(1,-1 \in Z\) such that \(g(1)=1\) and \(g(-1)=(-1)^4=1\)

i.e. \(\quad 1 \neq-1\) but \(g(1)=g(-1)\)

So, \(g\) is not a one-one function.

Let \(x, y \in R\) be such that

\(

h(x)=h(y) \Rightarrow x^3+4=y^3+4 \Rightarrow x^3=y^3 \Rightarrow x=y

\)

\(\therefore \quad h: R \rightarrow R\) is a one-one function.

Analyze function \(\phi(z)=z^3+4\).

Consider the complex cube roots of unity.

For example, \(z^3=1\) has solutions \(z=1, z=e^{i \frac{2 \pi}{3}}, z=e^{i \frac{4 \pi}{3}}\).

Let \(z_1=1\) and \(z_2=e^{i \frac{2 \pi}{3}}\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \phi\left(z_1\right)=1^3+4=5 \\

& \phi\left(z_2\right)=\left(e^{i \frac{z \pi}{3}}\right)^3+4=1+4=5

\end{aligned}

\)

Since \(z_1 \neq z_2\) but \(\phi\left(z_1\right)=\phi\left(z_2\right), \phi\) is not one-one.

Graphical Method:

Following steps may be used to check the injectivity of a function from its graph:

- Step 1: Draw the curve \(y=f(x)\).

- Step 2: If every line parallel to \(x\)-axis cuts the curve exactly at one point i.e. the curve has no bend or turn, then \(f(x)\) is one-one. Otherwise it is a many-one function. If there exists a line parallel to \(x\)-axis cutting the curve \(y=f(x)\) at more than one point, then \(f(x)\) is a many one function.

Example 22: Which one of the following functions is one-one?

(a) \(f: R \rightarrow R\) given by \(f(x)=|x-1|\) for all \(x \in R\)

(b) \(g:[-\pi / 2, \pi / 2] \rightarrow R\) given by \(g(x)=|\sin x|\) for all \(x \in[-\pi / 2, \pi / 2]\)

(c) \(h:[-\pi / 2, \pi / 2] \in R\) given by \(h(x)=\sin x\) for all \(x \in[-\pi / 2, \pi / 2]\)

(d) \(\phi: R \rightarrow R\) given by \(f(x)=x^2-4\) for all \(x \in R\).

Solution: (c)

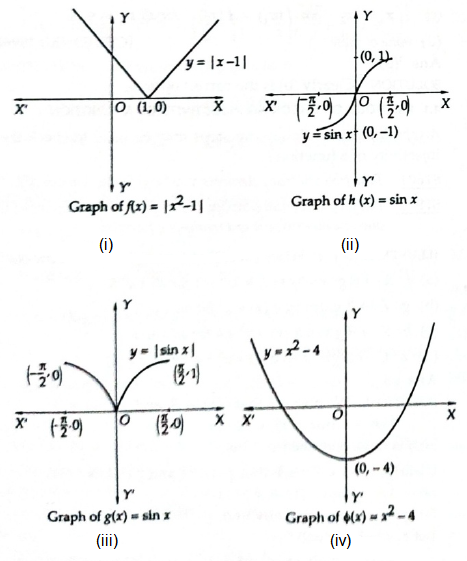

The graphs of \(f, g, h\) and \(\phi\) are as shown below:

It is evident from these graphs that \(h:[-\pi / 2, \pi / 2] \rightarrow R\) given by \(h(x)=\sin x\) is ne-one and all other functions are many-one as it is possible to draw horizontal lines cutting or intersecting the curves represented by them at more than one point.

Calculus Method:

A function function \(f: A \rightarrow B\) ( \(A\) and \(B\) are subsets of \(R\) ) is a one-one function iff it is either strictly increasing or strictly decreasing i.e. iff \(f^{\prime}(x)>0\) or \(f^{\prime}(x)<0\) for all \(x \in A\).

Example 23: Which one of the following functions is not one-one?

(a) \(f:(-1, \infty) \rightarrow R\) given by \(f(x)=x^2+2 x\)

(b) \(g:(1, \infty) \rightarrow R\) given by \(g(x)=e^{x^3-3 x+2}\)

(c) \(h: R \rightarrow R\) given by \(h(x)=2^{x(x-1)}\)

(d) \(\phi:(-\infty, 0) \rightarrow R\) given by \(\phi(x)=\frac{x^2}{x^2+1}\)

Solution: (c)

We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(x)=x^2+2 x, x \in(-1, \infty) \\

\Rightarrow & f^{\prime}(x)=2(x+1)>0 \text { for all } x \in(-1, \infty) \\

\Rightarrow & f(x) \text { is one-one. }

\end{aligned}

\)

It is given that \(g(x)=e^{x^3-3 x+2}, x \in(1, \infty)\)

\(\therefore \quad g^{\prime}(x)=e^{x^3-3 x+2} \times 3\left(x^2-1\right)>0\) for all \(x \in(1, \infty)\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad g(x)\) is one-one.

We have,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& h(x)=2^{x(x-1)} \\

\Rightarrow & h^{\prime}(x)=2^{x(x-1)}(2 x-1) \\

\Rightarrow & h^{\prime}(x)>0 \text { for all } x>\frac{1}{2} \text { and } h^{\prime}(x)<0 \text { for all } x<\frac{1}{2} \\

\Rightarrow & h(x) \text { is not one-one. } \\

\because & \phi(x)=\frac{x^2}{x^2+1} \text { for all } x \in(-\infty, 0) \\

\therefore & \phi^{\prime}(x)=\frac{\left(x^2+1\right) 2 x-x^2 \times 2 x}{\left(x^2+1\right)^2} \\

\Rightarrow & f^{\prime}(x)=\frac{2 x}{\left(x^2+1\right)^2}<0 \text { for all } x \in(-\infty, 0) \\

\Rightarrow & \phi(x) \text { is one-one. }

\end{array}

\)

Example 24: If \(f: R \rightarrow R\) given by

\(

f(x)=x^3+(a+2) x^2+3 a x+5

\)

is one-one, then a belongs to the interval

(a) \((-\infty, 1)\)

(b) \((1, \infty)\)

(c) \((1,4)\)

(d) \((4, \infty)\)

Solution: (c)

Since \(f: R \rightarrow R\) is one-one. Therefore, \(f(x)\) is either strictly increasing or strictly decreasing.

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad f^{\prime}(x)>0 \text { or } f^{\prime}(x)<0 \text { for all } x \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 3 x^2+2 x(a+2)+3 a>0 \text { for all } x \in R \\

& \text { or, } \quad 3 x^2+2 x(a+2)+3 a<0 \text { for all } x \in R \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 3 x^2+2 x(a+2)+3 a>0 \text { for all } x

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 4(a+2)^2-36 a<0\left[\because a x^2+b x+c>0 \text { for all } x \Rightarrow \text { Disc }<0\right] \\

& \Rightarrow \quad 4\left(a^2+4 a+4-9 a\right)<0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad\left(a^2-5 a+4\right)<0 \Rightarrow(a-1)(a-4)<0 \Rightarrow 1<a<4

\end{aligned}\\

&\text { Hence, } f(x) \text { is one-one if } a \in(1,4) \text {. }

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 25: Determine if the relations are functions:

(i) \(\{(0,6),(1,7),(2,9),(4,6)\}\)

(ii) \(\{(-6,9),(7,3),(-8,5),(5,4)\}\)

(iii) \(\{(-8,4),(7,9),(-8,6),(0,5)\}\)

Solution:

(i) This relation is a function: each \(\boldsymbol{x}\) appears only once. It is a many-to-one mapping since 0 and 4 map to 6.

(ii) This relation is a function: each \(\boldsymbol{x}\) appears only once. It is a one-to-one mapping.

(iii) This relation is not a function: It is a one-to-many mapping since -8 maps to 4 and 6.

Let us consider some more examples to make the above mentioned concepts clear.

- Let \(f: R^{+} \rightarrow R\) where \(y^2=x\). This cannot be considered a function as each \(x \in R^{+}\)would have two images namely \(\pm \sqrt{x}\). Hence, it does not represent a function. Thus, it would be a relation.

- Let \(f:[-2,2] \rightarrow R\), where \(x^2+y^2=4\). Here \(y= \pm \sqrt{4-x^2}\), that means for every \(x \in[-2,2]\) we would have two values of \(y\) (except when \(x= \pm 2\) ). Hence, it does not represent a function.

- Let \(f: R \rightarrow R\) where \(y=x^3\). Here for each \(x \in R\) we would have a unique value of \(y\) in the set \(R\) (as cube of any two distinct real numbers are distinct). Hence, it would represent a function.

Example 26: Let \(A=\{1,2,3\}, B=\{2,3,4\}\) be two sets. Which one of the following subsets of \(A \times B\) defines a function from \(A\) to \(B\)?

(a) \(f_1=\{(1,2),(2,3),(3,4)\}\)

(b) \(f_2=\{(1,2),(1,3),(2,3),(3,4)\}\)

(c) \(f_3=\{(1,3)(2,4)\}\)

(d) \(f_4=\{(1,4),(2,4),(3,4),(2,3)\}\)

Solution: (a) We observe that corresponding to each element in \(A\) there is unique ordered pair in \(f_1\). So, \(f_1\) is a function from \(A\) to \(B . f_2\) is not a function, becasue there are two ordered pairs \((1,2)\) and \((1,3)\) in \(f_3\) corresponding to \(1 \in A\).

As there is no ordered pair in \(f_3\) corresponding to \(3 \in A\). So, it is not a function from \(A\) to \(B\).

Similarly, \(f_4\) is not a function from \(A\) to \(B\) as there are two ordered pairs \((2,3)\) and \((2,4)\) in \(f_4\) corresponding to \(2 \in A\).

Example 27: If \(A=\{1,2,3,4\}\), then which of the following are functions from \(A\) to itself?

(a) \(f_1=\{(x, y): y=x+1\}\)

(b) \(f_2=\{(x, y): x+y>4\}\)

(c) \(f_3=\{(x, y) ; y<x\}\)

(d) \(f_4=\{(x, y): x+y=5\}\)

Solution: (d) We have, \(f_1=\{(1,2),(2,3),(3,4)\}\),

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f_2=\{(1,4)(2,3),(2,4),(3,3),(3,4),(4,4),(4,1),(4,2),(4,3)\}, \\

& f_3=\{(2,1),(3,1)(3,2) \ldots\} \text { and } f_4=\{(1,4),(2,3),(3,2),(4,1)\} .

\end{aligned}

\)

Obviously, \(f_4\) is a function from \(A\) to itself and \(f_1, f_2, f_3\) are not functions from \(A\) to itself.

Example 28: If function \(f=\{(1,1),(2,3),(3,5),(4,7)\}\) is described by a linear relation, then \(f(x)=\)

(a) \(2 x-1\)

(b) \(2 x+1\)

(c) \(x+2\)

(d) \(x-2\)

Solution: (a)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { Let } f(x)=a x+b \\

& \text { We have, } f(1)=1, f(2)=3, f(3)=5 \text { and } f(4)=7 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a+b=1,2 a+b=3,3 a+b=5 \text { and } 4 a+b=7 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad a=2 \text { and } b=-1 \\

& \text { Hence, } f(x)=2 x-1 \text {. }

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 29: If \(A=\left\{x: \frac{\pi}{6} \leq x \leq \frac{\pi}{3}\right\}\) and \(f: A \rightarrow R\) is given by \(f(x)=\cos x-x(1+x)\), then \(f(A)\) is equal to

(a) \(\left[\frac{\pi}{6}, \frac{\pi}{3}\right]\)

(b) \(\left[-\frac{\pi}{3},-\frac{\pi}{6}\right]\)

(c) \(\left[\frac{1}{2}-\frac{\pi}{3}\left(1+\frac{\pi}{3}\right), \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}-\frac{\pi}{6}\left(1+\frac{\pi}{6}\right)\right]\)

(d) \(\left[\frac{1}{2}+\frac{\pi}{3}\left(1-\frac{\pi}{3}\right), \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}+\frac{\pi}{6}\left(1-\frac{\pi}{6}\right)\right]\)

Solution: (c)

Since \(f(x)\) is a continuous decreasing function on \([\pi / 6, \pi / 3]\). Therefore, \(f(x)\) attains every value between its minimum and maximum values

\(

f\left(\frac{\pi}{3}\right)=\frac{1}{2}-\frac{\pi}{3}\left(1+\frac{\pi}{3}\right)

\)

and, \(f\left(\frac{\pi}{6}\right)=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}-\frac{\pi}{6}\left(1+\frac{\pi}{6}\right)\) respectively.

Hence,

\(

f(A)=\text { Range of } f(x)=\left[\frac{1}{2}-\frac{\pi}{3}\left(1+\frac{\pi}{3}\right), \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}-\frac{\pi}{6}\left(1+\frac{\pi}{6}\right)\right]

\)

Example 30: If \(f(x)=\cos \left(\log _e x\right)\), then \(f(x) f(y)-\frac{1}{2}\left\{f\left(\frac{x}{y}\right)+f(x y)\right\}\) is equal to

(a) 0

(b) \(\frac{1}{2} f(x) f(y)\)

(c) \(f(x+y)\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (a)

We have, \(f(x)=\cos \left(\log _e x\right)\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\therefore \quad & f(x) f(y)-\frac{1}{2}\left\{f\left(\frac{x}{y}\right)+f(x y)\right\} \\

& =\cos (\log x) \cos (\log y)-\frac{1}{2}\left\{\cos \log \left(\frac{x}{y}\right)+\cos (\log (x y))\right\} \\

& =\cos (\log x) \cos (\log y)-\frac{1}{2}\{\cos (\log x-\log y) \\

& \quad+\cos (\log x+\log y)\} \\

& =\cos (\log x) \cos (\log y)-\frac{1}{2}\{2 \cos (\log x) \cos (\log y)\} \\

& =0

\end{aligned}

\)

EQUAL FUNCTIONS

Two functions \(f: A \rightarrow B\) and \(g: C \rightarrow D\) are said to be equal iff

- \(A=C\) i.e. Domain of \(f=\) Domain of \(g\)

- \(B=D\) i.e. Co-domain of \(f=C o\)-domain of \(g\)

- \(f(x)=g(x)\) for every \(x\) belonging to their common domain.

Note: Two functions are equal if they have the same domain and codomain and their values are the same for all elements of the domain.

Example 31: The domain for which functions \(f(x)=2 x^2-1\) and \(g(x)=1-3 x\) are equal, is

(a) \(\{2,-1 / 2\}\)

(b) \(|-2,1 / 2|\)

(c) \(\{1,2\}\)

(d) \(\{-2,-1 / 2\}\)

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(x)=g(x) \\

\Rightarrow & 2 x^2-1=1-3 x \\

\Rightarrow & 2 x^2+3 x-2=0 \Rightarrow(2 x-1)(x+2)=0 \Rightarrow x=-2, \frac{1}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, \(f(x)=g(x)\) for all \(x \in\left\{-2, \frac{1}{2}\right\}\)

Example 32: If function \(f\) and \(g\) given by \(f(x)=\log (x-1)-\log (x-2)\) and \(g(x)=\log \left(\frac{x-1}{x-2}\right)\) are equal, then \(x\) lies in the interval

(a) \([1,2]\)

(b) \([2, \infty)\)

(c) \((2, \infty)\)

(d) \((-\infty, \infty)\)

Solution: (c) \(f(x)\) is defined for all \(x\) satisfying \(x-1>0\) and \(x-2>0\) i.e. \(x>2\)

\(

\therefore \quad \operatorname{Domain}(f)=(2, \infty)

\)

\(g(x)\) is defined for all \(x\) satisfying

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& \frac{x-1}{x-2}>0 \Rightarrow x \in(-\infty, 1) \cup(2, \infty) \\

\therefore \quad & \text { Domain }(g)=(-\infty, 1) \cup(2, \infty)

\end{array}

\)

Thus, \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\) are equal for all \(x\) belonging to their common domain i.e. \((2, \infty)\).

NUMBER OF FUNCTIONS

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be two finite sets having \(m\) and \(n\) elements respectively. Then, each element of set \(A\) can be associated to any one of \(n\) elements of set \(A\). So, total number of functions from set \(A\) to set \(B\) is equal to the number of ways of doing \(m\) jobs where each job can be done in \(n\) ways. The total number of such ways is

\(

\begin{gathered}

n \times n \times n \ldots \ldots . . \times n \\

m \text {-times }

\end{gathered}

\)

Hence, the total number of functions from \(A\) to \(B\) is \(n^m\)

Example 33: If \(A=\{1,2,3\}, B=\{x, y\}\), then the number of functions that can be defined from \(A\) into \(B\) is

(a) 12

(b) 8

(c) 6

(d) 3

Solution: (b) Total number of functions from \(A\) to \(B=2^3=8\)

Example 34: Let \(A\) be a set containing 10 distinct elements, then the total number of distinct functions from \(A\) to \(A\) is

(a) 10 !

(b) \(10^{10}\)

(c) \(2^{10}\)

(d) \(2^{10}-1\)

Solution: (b) Total number of functions \(=10^{10}\).

Example 35: If \(P=\{a, b, c\}\) and \(Q=\{1,2\}\), then the total number of relations from \(P\) to \(Q\) which are not functions, is

(a) 56

(b) 8

(c) 9

(d) 55

Solution: (a) We have,

Total number of relations from \(A\) to \(B=2^{3 \times 2}=64\)

Total number of functions from \(A\) to \(B=2^3=8\)

Total number of relations which are not functions

\(

=64-8=56

\)

Example 36: Identify the function described below are one-one or many-one?

Solution: (a) Graph of \(f(x)=3 x+5\) (one-one function) (b) Graph of \(f(x)=x^2+1\) (many-one function)

- Note: Lines drawn parallel to the \(x\)-axis from the each corresponding image point should intersect the graph of \(y=f(x)\) at one (and only one) point if \(f(x)\) is one-one and there will be at least one line parallel to \(x\)-axis that will cut the graph at least at two different points if \(f(x)\) is many-one and vice versa.

- Note that a many-one function can be made one-one by restricting the domain of the original function.

NUMBER OF ONE-ONE FUNCTIONS

If \(A\) and \(B\) are finite sets having \(m\) and \(n\) elements respectively such that \(m \leq n\), then to define a one-one function from \(A\) to \(B\), we have to relate \(m\) elements in \(A\) to \(n\) distinct elements in \(B\). For this, we first select \(m\) elements out of \(n\) elements in \(B\). This can be done in \({ }^n C_m\) ways. Now, we relate \(m\) elements in \(A\) to \(m\) distinct selected elements in \(B\) which can be done in \(m\) ! ways. Therefore, total number of one-one functions from \(A\) to \(B\) is \({ }^n C_m \times m!\). If \(m>n\), then it is not possible to define a one-one function from \(A\) to \(B\). Thus, we have

Number of one-one functions from \(A\) to \(B\)

\(

=\left\{\begin{array}{cc}

{ }^n C_m \times m! & , \text { if } m \leq n \\

0 & , \text { if } m>n

\end{array}\right.

\)

Alternate way: \(n P m=\frac{n!}{(n-m)!} \quad [{ }^n C_m=\frac{n!}{m!(n-m)!}]\)

where \(n \mathrm{Pm}\) is the permutation of \(n\) items taken \(m\) at a time, \(n!\) is the factorial of \(n\), and \((n-m)!\) is the factorial of \((n-m)\).

Example 37: Set \(A\) has 3 elements and set \(B\) has 4 elements. The number of injections that can be defined from \(A\) to \(B\) is

(a) 144

(b) 12

(c) 24

(d) 64

Solution: (c) The total number of injective mappings from a set \(A\) containing 3 elements to a set \(B\) containing 4 elements is equal to the total number of arrangements of 4 by taking 3 at a time i.e. \({ }^4 C_3 \times 3!=24\).

Onto function (surjective function) and Into Function

Onto function:

In the mapping \(f: A \rightarrow B\) such

\(f(A)=B\)

i.e., Range \(=\) Codomain

Then, the function is Onto.

Into function:

In the mapping \(f: A \rightarrow B\) such

\(f(A) \subset B\),

i.e. Range \(\subset\) Codomain, then the function is Into.

Note: Onto function is also called surjective function and a function which is both one-one and onto is called bijective function.

Method to Test Onto or Into Mapping

- Step 1: Choose an arbitrary element \(y\) in \(B\).

- Step 2: Put \(f(x)=y\)

- Step 3: Solve the equation \(f(x)=y\) for \(x\) and obtain \(x\) in terms of \(y\).

\(

\text { Let } x=g(y)

\) - Step 4: If for all values of \(y \in B\), the values \(x\) obtained from \(x=g(y)\) are in \(A\), then \(f\) is onto.

If there are some \(y \in B\) for which \(x\), given by \(x=g(y)\), is not in A. Then, \(f\) is not onto (into function).

Example 38: Let \(f: N \rightarrow Z\) be a function defined as \(f(x)=x-1000\). Show that \(f\) is an into function.

Solution: Let \(f(x)=y=x-1000\)

\(

\Rightarrow x=y+1000=g(y) \text { (say) }

\)

Here, \(g(y)\) is defined for each \(y \in I\), but \(g(y) \notin N\) for \(y \leq-1000\). Hence, \(f\) is into.

Explanation: The function is \(f: N \rightarrow Z\).

The function is defined as \(f(x)=x-1000\).

An into function means the range is a proper subset of the codomain.

The set of natural numbers \(N=\{1,2,3, \ldots\}\).

The set of integers \(Z=\{\ldots,-2,-1,0,1,2, \ldots\}\).

How to solve?

Determine the range of the function and show it is a proper subset of the codomain.

Step 1: Determine the range of the function.

The domain is \(N=\{1,2,3, \ldots\}\).

For \(x=1, f(1)=1-1000=-999\).

For \(x=2, f(2)=2-1000=-998\).

The range of \(f\) is \(R=\{-999,-998,-997, \ldots\}\).

Step 2: Compare the range with the codomain.

The codomain is \(Z=\{\ldots,-2,-1,0,1,2, \ldots\}\).

The range \(R=\{-999,-998,-997, \ldots\}\) is a subset of \(Z\).

Therefore, \(\boldsymbol{R} \subset \boldsymbol{Z}\).

Step 3: Since the range \(R\) is a proper subset of the codomain \(Z\), the function \(f\) is an into function.

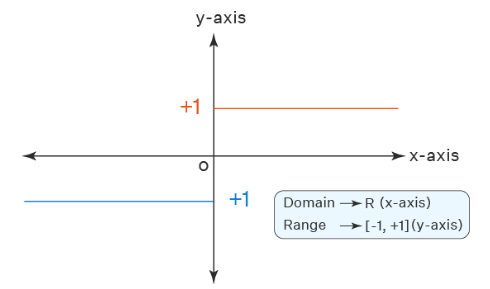

Example 39: Let \(f: R \rightarrow R\) where \(f(x)=\sin x\). Show that \(f\) is into.

Solution: The given function is \(f(x)=\sin x\), where the domain is \(\boldsymbol{R}\) (all real numbers) and the codomain is also \(\boldsymbol{R}\) (all real numbers).

The properties of the sine function state that its values always lie within the interval \([-1,1]\). Thus, the range of the function \(f(x)=\sin x\) is \([-1,1]\).

Comparing the range and the codomain:

Range: \([-1,1]\)

Codomain: \(\boldsymbol{R}\) (all real numbers)

Since the range \([-1,1]\) is a proper subset of the codomain \(\boldsymbol{R}\) (meaning there are elements in \(\boldsymbol{R}\) like 2 or -5 that are not in the range), the function \(f(x)=\sin x\) is an into function.

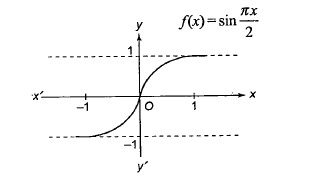

Example 40: Let \(A=\{x:-1 \leq x \leq 1\}=B\) be a mapping \(f: A \rightarrow B\).

then, function \(f(x)=\sin \frac{\pi x}{2}\) is into or onto?

Solution: The domain is \(A=\{x:-1 \leq x \leq 1\}\).

The codomain is \(\boldsymbol{B}=\{x:-1 \leq x \leq 1\}\).

The function is \(f(x)=\sin \frac{\pi x}{2}\).

A function is onto (surjective) if its range equals its codomain.

A function is into if its range is a proper subset of its codomain.

How to solve?

We need to find the range of the function \(f(x)\) over the given domain and compare it to the codomain.

The argument of the sine function is \(\frac{\pi x}{2}\).

Given \(-1 \leq x \leq 1\).

Multiply by \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) : \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \frac{\pi x}{2} \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\).

The range of \(\sin \theta\) for \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\) is \([-1,1]\).

So, the range of \(f(x)=\sin \frac{\pi x}{2}\) is \([-1,1]\).

The range of \(f(x)\) is \([-1,1]\).

The codomain \(\boldsymbol{B}\) is \([-1,1]\).

Since the range equals the codomain, the function is onto.

The graph shows that \(f(x)\) is one-one and onto as range \(=\) co-domain.

Therefore, \(f(x)\) is bijective.

Example 41: If \(f: R \rightarrow R, f(x)=\left\{\begin{aligned} x|x|-4, & x \in Q \\ x|x|-\sqrt{3}, & x \notin Q\end{aligned}\right.\), then identify the type of function.

Solution: The function is defined as \(f: R \rightarrow R\).

\(f(x)=x|x|-4\) when \(x \in Q\) (rational numbers).

\(f(x)=x|x|-\sqrt{3}\) when \(x \notin Q\) (irrational numbers).

How to solve?

Determine if the function is one-to-one (injective) and onto (surjective) to classify its type.

Step 1: Check if the function is one-to-one.

A function is one-to-one if \(f\left(x_1\right)=f\left(x_2\right)\) implies \(x_1=x_2\).

Consider \(f(x)=0\).

If \(x \in Q, x|x|-4=0 \Rightarrow x|x|=4\).

If \(x \geq 0, x^2=4 \Rightarrow x=2\).

If \(x<0,-x^2=4 \Rightarrow x^2=-4\), which has no real solutions.

So, \(f(2)=0\).

If \(x \notin Q, x|x|-\sqrt{3}=0 \Rightarrow x|x|=\sqrt{3}\).

If \(x \geq 0, x^2=\sqrt{3} \Rightarrow x=3^{1 / 4}\).

If \(x<0,-x^2=\sqrt{3} \Rightarrow x^2=-\sqrt{3}\), which has no real solutions.

So, \(f\left(3^{1 / 4}\right)=0\).

Since \(f(2)=f\left(3^{1 / 4}\right)=0\) and \(2 \neq 3^{1 / 4}\), the function is not one-to-one (many to one).

Step 2: Check if the function is onto.

A function is onto if its range equals its codomain, which is \(R\).

The range of \(x|x|\) is \(R\).

The range of \(x|x|-4\) is \(R\).

The range of \(x|x|-\sqrt{3}\) is \(R\).

However, the function \(f(x)\) cannot take certain values.

For example, \(f(x) \neq \sqrt{3}\) for any \(x \in R\).

Since there exists a value in the codomain ( \(R\) ) that is not in the range of \(f(x)\), the function is not onto (into function).

Example 42: If the function \(f: R \rightarrow A\) given by \(f(x)=\frac{x^2}{x^2+1}\) is surjection, then find \(A\).

Solution: The domain of \(f(x)\) is all real numbers.

Since, \(f: R \rightarrow A\) is surjective, therefore \(A\) must be the range of \(f(x)\).

Let \(f(x)=y\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow y=\frac{x^2}{x^2+1} \\

& \Rightarrow x^2 y+y=x^2 \\

& \Rightarrow x=\sqrt{\frac{y}{1-y}} \text { exists, if } \frac{y}{1-y} \geq 0

\end{aligned}

\)

\(\Rightarrow 0 \leq y<1\). Hence, \(A \in[0,1)\).

Explanation:

The function is \(f: R \rightarrow A\).

The function is given by \(f(x)=\frac{x^2}{x^2+1}\).

The function is a surjection.

For a surjective function, the codomain \(A\) is equal to its range.

How to solve?

Find the range of the function \(f(x)=\frac{x^2}{x^2+1}\).

Step 1: Determine the lower bound of the range.

Since \(x^2 \geq 0\) for all real \(x\), and \(x^2+1>0\), the fraction \(\frac{x^2}{x^2+1} \geq 0\).

When \(x=0, f(0)=\frac{0^2}{0^2+1}=\frac{0}{1}=0\).

So, the minimum value is 0 , and it is included in the range.

Step 2: Determine the upper bound of the range.

Rewrite \(f(x)\) as \(f(x)=\frac{x^2+1-1}{x^2+1}=\frac{x^2+1}{x^2+1}-\frac{1}{x^2+1}=1-\frac{1}{x^2+1}\).

Since \(x^2 \geq 0\), we have \(x^2+1 \geq 1\).

This implies \(0<\frac{1}{x^2+1} \leq 1\).

Therefore, \(1-1 \leq 1-\frac{1}{x^2+1}<1-0\).

So, \(0 \leq f(x)<1\).

The value 1 is never reached, as \(\frac{1}{x^2+1}\) can never be 0.

The range of \(f(x)\) is \([0,1)\).

Since \(f\) is a surjection, \(A\) must be equal to the range.

NUMBER OF ONTO FUNCTIONS

If \(A\) and \(B\) are two sets having \(m\) and \(n\) elements respectively such that \(1 \leq n \leq m\), then the number of onto functions from \(A\) to \(B\) is equal to the

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { Coefficient of } x^m \text { in } m!\left(e^x-1\right)^n \\

& =m!\times \text { Coefficient of } x^m \text { in }\left(e^x-1\right)^n \\

& =m!\times \text { Coefficient of } x^m \text { in } \sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r\left(e^x\right)^r(-1)^{n-r} \\

& =m!\times \text { Coefficient of } x^m \text { in } \sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r(-1)^{n-r}\left(\sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{(r x)^k}{k!}\right) \\

& =m!\times \sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r(-1)^{n-r} \frac{r^m}{m!} \\

& =\sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r(-1)^{n-r} r^m=\sum_{r=1}^n{ }^n C_r(-1)^{n-r} r^m

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 43: The total number of onto functions from the set \(\{1,2,3,4\}\) to the set \(\{3,4,7\}\) is

(a) 18

(b) 36

(c) 64

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) If \(A\) and \(B\) are two sets consisting of \(m\) and \(n\) elements respectively such that \(1 \leq n \leq m\), then number of onto functions from \(A\) to \(B\) is

\(

\sum_{r=1}^n(-1)^{n-r}{ }^n C_r r^m

\)

Here, \(m=4\) and \(n=3\).

So, total number of onto functions

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =\sum_{r=1}^3(-1)^{3-r{ }^3 C_r r^4} \\

& ={ }^3 C_1-{ }^3 C_2 \times 2^4+{ }^3 C_3 \times 3^4=3-48+81=36 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Constant Function

Constant Function is a specific type of mathematical function that, as its name suggests, outputs will always be the same value for any input. In other words, the output of a constant function remains constant.

The function \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is known as a constant function, if the range of \(B\) has only one element.

For all \(x \in A, f(x)=C\), where as \(C \in B\). \(f(x)=C\) for all \(x \in A\) means every element in the domain \(A\) maps to the same constant value \(C\) in the codomain \(B\).

If the function \(f: \mathbf{} \mathbf{R} \rightarrow \mathbf{R}\) defined by \(y=f(x)=\mathbf{C}, x \in \mathbf{R}\), where C is a constant \(\in \mathbf{R}\), is a constant function.

Domain of \(f=\mathbf{R}\)

Range of \(f=\{\mathrm{C}\}\)

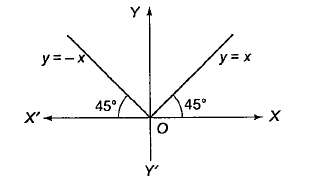

Identity Function

The identity function is a function that returns the same value that was used as its input. The function \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is known as an identity function, if \(f(a)=a, \forall a \in A\) and it is denoted by \(I_A\).

Example:

If the input is \(\mathbf{2}\), then the output is \(\mathbf{2}\). If the input is \(\mathbf{4}\), the output is \(\mathbf{4}\) and so on. Representing it as a set of ordered pairs:

\(

f=\{(2,2),(4,4),(6,6)\}

\)

The function \(f: \mathbf{R} \rightarrow \mathbf{R}\) defined by \(y=f(x)=x\) for each \(x \in \mathbf{R}\) is called the identity function.

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { Domain of } f=\mathbf{R} \\

& \text { Range of } f=\mathbf{R}

\end{aligned}

\)

Remark

- \(I_A\) is bijective or bijection: Yes, the identity function is bijective. A bijective function, also known as a bijection, is both injective (one-to-one) and surjective (onto). The identity function, which maps each element to itself, satisfies both of these properties, making it a bijection.

Inverse of a Function

If \(f: A \rightarrow B\) be one-one and onto function, let \(b \in B\), then there exist exactly one element \(a \in A\) such that \(f(a)=b\), so we may define

\(

\begin{aligned}

f^{-1}: B \rightarrow A: f^{-1}(b) & =a \\

\Leftrightarrow \quad f(a) & =b

\end{aligned}

\)

The function \(f^{-1}\) is called the inverse of \(f\). A functions is invertible iff \(f\) is one-one onto.

Remark

- \(f^{-1}(b) \subseteq A\)

- If \(f: A \rightarrow B\) and \(g: B \rightarrow A\), then \(f\) and \(g\) are said to be invertible.

- The inverse of a bijection is unique.

- The inverse of a bijection is also a bijection.

- If \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is a bijection and \(g: B \rightarrow A\) is the inverse of \(f\), then \(f \circ g=I_B\) and \(g \circ f=I_A\), where \(I_A\) and \(I_B\) are the identity functions on the sets \(A\) and \(B\) respectively.

METHODS OF FINDING THE INVERSE OF A BIJECTION

METHOD I:

- Step 1: Obtain the bijection, let it be \(f: A \rightarrow B\).

- Step 2: Put \(f(x)=y\), where \(y \in B\) and \(x \in A\).

- Step 3: Solve \(f(x)=y\) to obtain \(x\) in terms of \(y\).

- Step 4: Replace \(x\) by \(f^{-1}(y)\) in the relation obtained in step 3 to obtain the inverse off.

Example 44: If \(f: R \rightarrow R\) is given by \(f(x)=3 x-5\), then \(f^{-1}(x)\)

(a) is given by \(\frac{1}{3 x-5}\)

(b) is given by \(\frac{x+5}{3}\)

(c) does not exist because \(f\) is not one-one

(d) does not exist because \(f\) is not onto

Solution:

Step 1: Obtain the bijection

Clearly, \(f: R \rightarrow R\) is a one-one onto function. So, it is invertible.

Step 2: Put \(f(x)=y\), where \(y \in B\) and \(x \in A\).

Step 3: Solve \(f(x)=y\) to obtain \(x\) in terms of \(y\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Let } f(x)=y \text {. Then, }\\

&3 x-5=y \Rightarrow x=\frac{y+5}{3}

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 4: Replace \(x\) by \(f^{-1}(y)\) in the relation obtained in step 3 to obtain the inverse off

\(

f^{-1}(y)=\frac{y+5}{3}

\)

\(

\text { Hence, } f^{-1}(x)=\frac{x+5}{3}

\)

Example 45: Let \(f:[4, \infty) \rightarrow[4, \infty)\) be defined by \(f(x)=5^{x(x-4)}\). Then, \(f^{-1}(x)\) is

(a) \(2-\sqrt{4+\log _5 x}\)

(b) \(2+\sqrt{4+\log _5 x}\)

(c) \(\left(\frac{1}{5}\right)^{x(x-4)}\)

(d) not defined

Solution: (b)

Clearly, \(f:[4, \infty) \rightarrow[4, \infty)\) is a bijection. So, it is invertible.

Let \(f(x)=y\). Then,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& 5^{x(x-4)}=y \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-4 x=\log _5 y \\

\Rightarrow & x^2-4 x-\log _5 y=0 \\

\Rightarrow & x=\frac{4 \pm \sqrt{16+4 \log _5 y}}{2}

\end{array}

\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow \quad f^{-1}(y)=2+\sqrt{4+\log _5 y} & {[\because x \geq 4]} \\

\text { Hence, } f^{-1}(x)=2+\sqrt{4+\log _5 x} &

\end{array}

\)

METHOD II:

- Step 1: Obtain the bijection \(f(x)\).

- Step 2: In the formula for \(f(x)\) replace \(f(x)\) by \(x\) and \(x\) by \(f^{-1}(x)\).

- Step 3: Simplify the relation obtained in step 2 to get \(f^{-1}(x)\).

Example 46: If \(f(x)=\frac{1-x}{1+x}, x \neq-1\), then \(f^{-1}(x)\) equals to

(a) \(f(x)\)

(b) \(\frac{1}{f(x)}\)

(c) \(-f(x)\)

(d) \(-\frac{1}{f(x)}\)

Solution: (a) Replacing \(f(x)\) by \(x\) and \(x\) by \(f^{-1}(x)\) in \(f(x)=\frac{1-x}{1+x}\), we get

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=\frac{1-f^{-1}(x)}{1+f^{-1}(x)} \Rightarrow \frac{x+1}{x-1}=\frac{2}{-2 f^{-1}(x)} \\

\Rightarrow & f^{-1}(x)=\frac{1-x}{1+x}=f(x)

\end{aligned}

\)

Composition of Functions

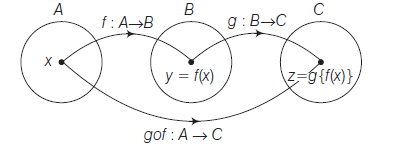

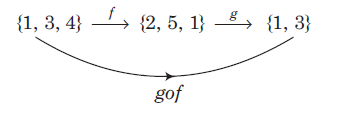

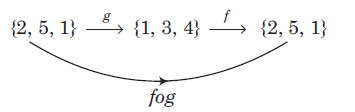

Let \(A, B\) and \(C\) be three non-empty sets. Let \(f: A \rightarrow B\) and \(g: B \rightarrow C\) be two mappings, then gof \(: A \rightarrow C\). This function is called the product or composite of \(f\) and \(g\), given by \((g \circ f) x=g\{f(x)\}, \forall x \in A\).

Example 47: If \(g(x)=x^2+x-2\) and \(\frac{1}{2} g \circ f(x)=2 x^2-5 x+2\), then \(f(x)\) is equal to

(a) \(2 x-3\)

(b) \(2 x+3\)

(c) \(2 x^2+3 x+1\)

(d) \(2 x^2-3 x-1\)

Solution: (a) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{1}{2} g o f(x)=2 x^2-5 x+2 \\

\Rightarrow & g(f(x))=4 x^2-10 x+4 \\

\Rightarrow & (f(x))^2+f(x)-2=4 x^2-10 x+4 \\

\Rightarrow & (f(x))^2+f(x)-\left(4 x^2-10 x+6\right)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & f(x)=\frac{-1 \pm \sqrt{1+4\left(4 x^2-10 x+6\right)}}{2} \\

\Rightarrow & f(x)=\frac{-1 \pm \sqrt{16 x^2-40 x+25}}{2} \\

\Rightarrow & f(x)=\frac{-1 \pm(4 x-5)}{2}=2 x-3,-2 x+2

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 48: If \(f(x)=\sin ^2 x\) and the composite function \(g(f(x))=|\sin x|\), then \(g(x)\) is equal to

(a) \(\sqrt{x-1}\)

(b) \(\sqrt{x}\)

(c) \(\sqrt{x+1}\)

(d) \(-\sqrt{x}\)

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

f(x)=\sin ^2 x \text { and } g(f(x))=|\sin x|

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{array}{rlrl}

& g(f(x)) =|\sin x| \\

\Rightarrow & g(f(x)) =\sqrt{\sin ^2 x} \Rightarrow g\left(\sin ^2 x\right)=\sqrt{\sin ^2 x} \\

\therefore & g(x) =\sqrt{x}

\end{array}

\)

Example 49: If

\(

f(x)=\sin ^2 x+\sin ^2\left(x+\frac{\pi}{3}\right)+\cos \left(x+\frac{\pi}{2}\right) \cos x

\)

and \(g(5 / 4)=1\), then \(g \circ f(x)\) is

(a) a polynomial of first degree in \(\sin x\) and \(\cos x\)

(b) a constant function

(c) a polynomial of second degree in \(\sin x\) and \(\cos x\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

f(x)=\sin ^2 x+\sin ^2\left(x+\frac{\pi}{3}\right)+\cos \left(x+\frac{\pi}{3}\right) \cos x

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad f(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left\{1-\cos 2 x+1-\cos \left(2 x+\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)\right. \\

& \left.\quad+\cos \left(2 x+\frac{\pi}{3}\right)+\cos \frac{\pi}{3}\right\} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad f(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left[\frac{5}{2}-\left\{\cos 2 x+\cos \left(2 x+\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)\right\}+\cos \left(2 x+\frac{\pi}{3}\right)\right] \\

& \Rightarrow \quad f(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left[\frac{5}{2}-2 \cos \left(2 x+\frac{\pi}{3}\right) \cos \frac{\pi}{3}+\cos \left(2 x+\frac{\pi}{3}\right)\right] \\

& \Rightarrow \quad f(x)=\frac{5}{4}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\therefore \quad g \circ f(x)=g(f(x))=g\left(\frac{5}{4}\right)=1 \text { for all } x .\\

&\text { Hence, } g o f(x) \text { is a constant function. }

\end{aligned}

\)

PROPERTIES OF COMPOSITION OF FUNCTIONS

- The composition of functions is not commutative i.e. \(f o g \neq g o f .\)

- The composition of functions is associative i.e. \((f o g)\) oh \(=f o(g o h)\).

- The composition of two bijections is a bijection.

- Let \(f: A \rightarrow B\). Then, \(fo I_A=I_B of\) \(=f\)

i.e. the composition of any function with the identity function is the function itself. - Let \(f: A \rightarrow B, g: B \rightarrow A\) be two functions such that \(g o f=I_A\). Then, \(f\) is an injection and \(g\) is a surjection.

- Let \(f: A \rightarrow B\) and \(g: B \rightarrow A\) be two function such that \(f o g=I_B\). Then, \(f\) is a surjection and \(g\) is an injection.