11.8 Entrance Corner

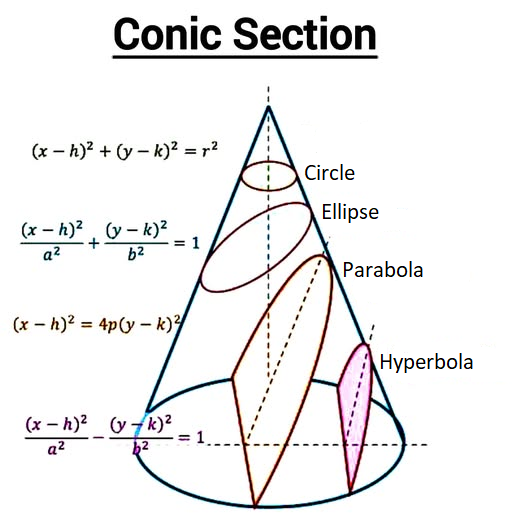

Conic Section

A conic section is a two-dimensional curve formed by the intersection of a plane and a three-dimensional double-napped cone. The four primary types of conic sections are the circle, ellipse, parabola, and hyperbola, which are defined by the angle and position of the intersecting plane relative to the cone.

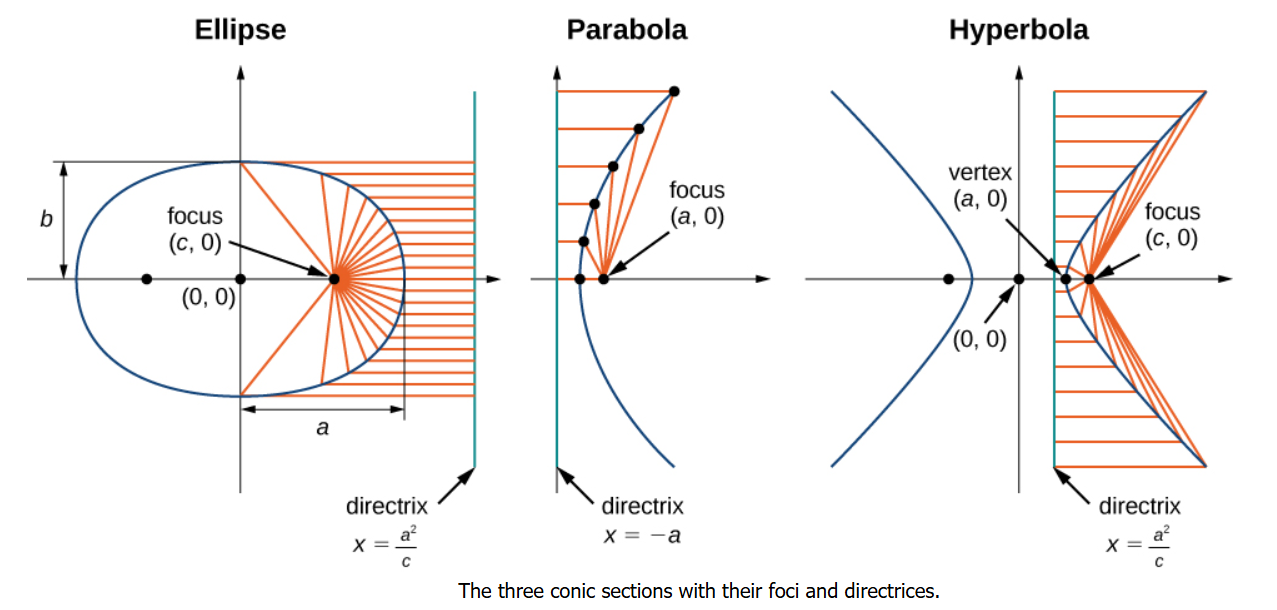

Eccentricity

Eccentricity ( \(e\)) is a measure that defines the shape of a conic section based on the ratio of the distance from any point on the curve to a focus to the distance from that same point to a fixed line called the directrix.

Directrix

A directrix is a fixed reference line used to define conic sections (parabolas, ellipses, and hyperbolas). For a parabola, it is a line perpendicular to the axis of symmetry, where any point on the parabola is equidistant from both the focus and this directrix. It lies outside the curve and does not touch it.

Key Characteristics of Conic Sections:

Circle: Formed when the plane is perpendicular to the cone’s axis.

Ellipse: Formed when the plane cuts through one nappe at a slant, creating a closed curve.

Parabola: Formed when the plane is parallel to the slope of the cone (the generator line).

Hyperbola: Formed when the plane intersects both nappes, creating two separate unbounded curves.

Eccentricity (\(e\)): Defines the shape based on the ratio of distances to a focus and a directrix: \(e=0\) (circle), \(0<e<1\) (ellipse), \(e=1\) (parabola), \(e>1\) (hyperbola).

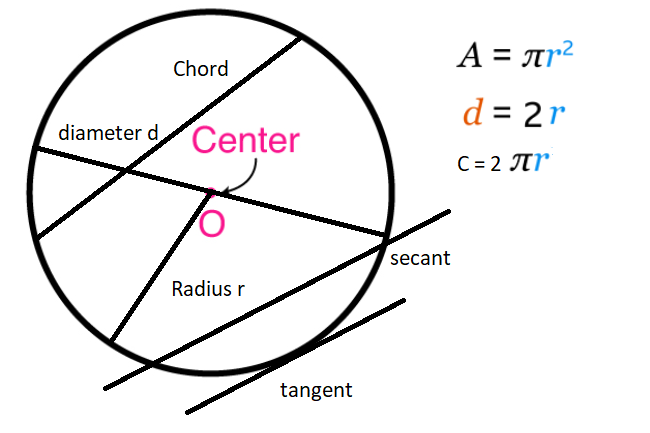

Circle

A circle is the locus of a point which moves in a plane such that its distance from a fixed point in plane is always a constant. The fixed point is called the centre and the constant distance is called the radius of the circle.

Center (Centre): The center is the point that is equidistant from all points on a circle. It is also called the origin.

Chord: A chord is a line segment with endpoints on the circle. The diameter is the longest chord.

Circumference: The circumference is the distance around a circle.

Secant: A secant is a chord that extends beyond the circle. In other words, it is a coplanar line that intersects a circle at two points.

Semicircle: A semicircle is an arc which has the diameter as endpoints and center as midpoint. The interior of a semicircle is a half-disc.

Tangent: A tangent is a coplanar line sharing one single point in common with a circle.

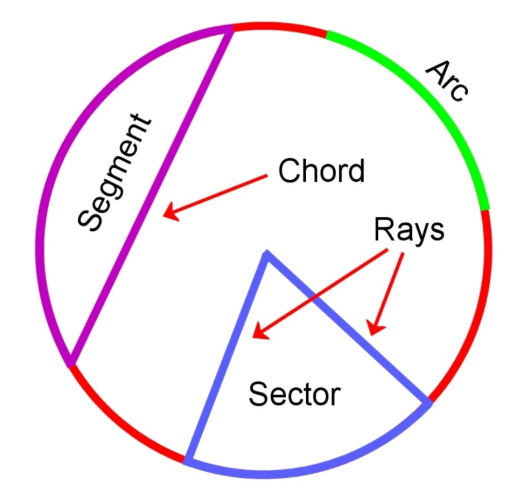

Arc: An arc is any segment of a circle formed by connected points.

Segment: A segment is an area bounded by an arc and a chord.

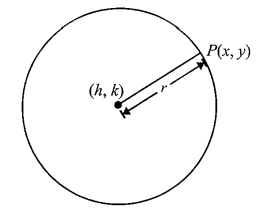

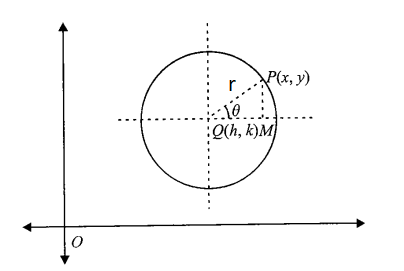

Equation of Circle with Centre \((h, k)\) and Radius \(r\)

The equation of circle is

\(

(x-h)^2+(y-k)^2=r^2

\)

In particular: If the centre is at the origin, the equation of circle is \(x^2+y^2=r^2\).

The Derivation:

Identify the coordinates: We place the center of the circle at \(C(h, k)\) and pick any arbitrary point on the edge of the circle, \(P(x, y)\). The distance between these two points is the radius, \(r\).

Apply the distance formula: The distance between any two points in a 2D plane is found using the formula \(d=\sqrt{\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2}\). Substituting our circle’s values, we get:

\(

r=\sqrt{(x-h)^2+(y-k)^2}

\)

Square both sides: To eliminate the radical and arrive at the standard form, we square both sides of the equation:

\(

r^2=(x-h)^2+(y-k)^2

\)

Note: Relate to Pythagoras: Notice that \((x-h)\) represents the horizontal distance and (\(y-k\)) represents the vertical distance. This creates a right triangle where \(r\) is the hypotenuse. Thus, the equation is simply a restatement of \(a^2+b^2=c^2\).

Remarks

- The above equation is known as the central form of the equation of a circle.

- If the centre of the circle is at the origin and radius is \(r\), then from the above form the equation of the circle is

\(

x^2+y^2=r^2

\)

Example 1: The radius of the circle passing through the point \((6,2)\), two of whose diameters are \(x+y=6\) and \(x+2 y=4\) is

Solution: To find the radius of the circle, we first need to identify its center and then calculate the distance from that center to the given point on the circle.

Step 1: Find the center of the circle

Since all diameters of a circle intersect at the center, we solve the system of linear equations formed by the two given diameters:

\(x+y=6\)

\(x+2 y=4\)

Subtracting the first equation from the second:

\(

\begin{gathered}

(x+2 y)-(x+y)=4-6 \\

y=-2

\end{gathered}

\)

Substituting \(y=-2\) back into the first equation:

\(

x+(-2)=6 \Longrightarrow x=8

\)

The center of the circle is \((h, k)=(8,-2)\).

Step 2: Calculate the radius using the distance formula

The radius \(r\) is the distance between the center \((8,-2)\) and the given point on the circle \((6,2)\). We use the formula derived from the equation of a circle:

\(

r=\sqrt{(x-h)^2+(y-k)^2}

\)

Substitute the coordinates:

\(

r=\sqrt{(6-8)^2+(2-(-2))^2}=\sqrt{20}

\)

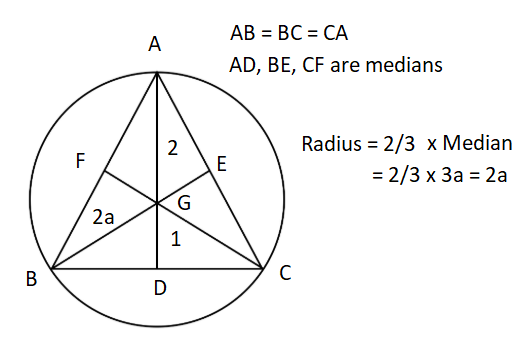

Example 2: The equation of a circle with origin as centre and passing through the vertices of an equilateral triangle whose median is of length \(3 a\) is [AIEEE 2002]

(a) \(x^2+y^2=9 a^2\)

(b) \(x^2+y^2=16 a^2\)

(c) \(x^2+y^2=4 a^2\)

(d) \(x^2+y^2=a^2\)

Solution: (c) To solve this, we need to find the relationship between the median of an equilateral triangle and its circumradius (the distance from the center to the vertices).

Step 1: Understand the geometry

In an equilateral triangle, the centroid, circumcenter, and orthocenter are all the same point. Since the circle’s center is at the origin \((0,0)\) and passes through the vertices, this origin is the circumcenter.

Step 2: Use the property of the centroid

The centroid (center) of a triangle divides each median in a ratio of \(2: 1\).

The part from the vertex to the centroid is the circumradius (\(R\)).

The part from the centroid to the base is the inradius (\(r\)).

Given that the total length of the median is \(3 a\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

R=\frac{2}{3} \times(\text { Length of Median }) \\

R=\frac{2}{3} \times(3 a) \\

R=2 a

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 3: Write the equation

Since the circle is centered at the origin \((0,0)\), we use the simplified form of the circle equation:

\(

x^2+y^2=R^2

\)

Substituting \(R=2 a\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

x^2+y^2=(2 a)^2 \\

x^2+y^2=4 a^2

\end{gathered}

\)

Example 3: The lines \(2 x-3 y-5=0\) and \(3 x-4 y=7\) are diameters of a circle of area \(154(=49 \pi)\) sq. units, then the equation of the circle is [AIEEE 2003, 2006]

(a) \(x^2+y^2+2 x-2 y-62=0\)

(b) \(x^2+y^2+2 x-2 y-47=0\)

(c) \(x^2+y^2-2 x+2 y-47=0\)

(d) \(x^2+y^2-2 x+2 y-62=0\)

Solution: (c) To solve this, we follow the same logic as before: find the intersection of the diameters to get the center, and use the area to find the radius.

Step 1: Find the center of the circle

The center \((h, k)\) is the point where the two diameters intersect. We solve the system:

\(2 x-3 y=5 \dots(i)\)

\(3 x-4 y=7 \dots(ii)\)

Solving (1) and (ii) \(y=-1\) and \(x=1\)

The center is \((1,-1)\).

Step 2: Find the radius squared \(\left(r^2\right)\)

We are given that the area is 154 sq. units, and the problem notes this is approximately \(49 \pi\).

Using the area formula:

\(

\text { Area }=\pi r^2

\)

\(

\begin{gathered}

49 \pi=\pi r^2 \\

r^2=49

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 3: Write the equation

Using the standard form \((x-h)^2+(y-k)^2=r^2\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

(x-1)^2+(y-(-1))^2=49 \\

(x-1)^2+(y+1)^2=49

\end{gathered}

\)

Now, expand the equation to match the options:

\(

\begin{gathered}

\left(x^2-2 x+1\right)+\left(y^2+2 y+1\right)=49 \\

x^2+y^2-2 x+2 y+2=49 \\

x^2+y^2-2 x+2 y-47=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Example 4: If the lines \(2 x+3 y+1=0\) and \(3 x-y-4=0\) lie along diameters of a circle of circumference \(10 \pi\), then the equation of the circle is [AIEEE 2004]

(a) \(x^2+y^2+2 x-2 y-23=0\)

(b) \(x^2+y^2-2 x-2 y-23=0\)

(c) \(x^2+y^2+2 x+2 y-23=0\)

(d) \(x^2+y^2-2 x+2 y-23=0\)

Solution: (d) This problem follows the same logical flow as the previous one, but with a slight twist: we are given the circumference instead of the area.

Step 1: Find the center of the circle

The center \((h, k)\) is the intersection point of the two diameter lines. Let’s solve the system:

\(2 x+3 y=-1 \dots(i)\)

\(3 x-y=4 \dots(ii)\)

Solving eqns (i) and (ii) we get

\(x=1\)

Substitute \(x=1\) into the second equation:

\(y=-1\)

The center of the circle is \((1,-1)\).

Step 2: Find the radius squared ( \(r^2\) )

The circumference of a circle is given by \(C=2 \pi r\).

\(

\begin{gathered}

10 \pi=2 \pi r \\

r=5 \\

r^2=25

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 3: Write the equation

Using the standard form \((x-h)^2+(y-k)^2=r^2\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

(x-1)^2+(y-(-1))^2=25 \\

(x-1)^2+(y+1)^2=25

\end{gathered}

\)

\(

x^2+y^2-2 x+2 y-23=0

\)

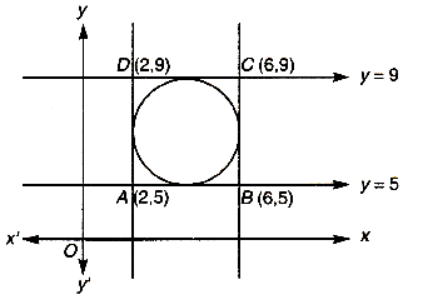

Example 5: The centre of the circle inscribed in the square formed by the lines \(x^2-8 x+12=0\) and \(y^2-14 y+45=0\), is [IIT (S) 2003]

(a) \((4,7)\)

(b) \((7,4)\)

(c) \((9,4)\)

(d) \((4,9)\)

Solution: (a) To find the center of a circle inscribed in a square, we first need to identify the boundaries (the four lines) that form the square.

Step 1: Solve for the boundary lines

The problem gives us two quadratic equations, each representing a pair of parallel lines.

For the vertical lines (\(x\)):

\(

x^2-8 x+12=0

\)

Factoring the quadratic: \((x-2)(x-6)=0\). So, the lines are \(x=2\) and \(x=6\).

For the horizontal lines (\(y\)):

\(

y^2-14 y+45=0

\)

Factoring the quadratic: \((y-5)(y-9)=0\). So, the lines are \(y=5\) and \(y=9\).

Step 2: Identify the square’s dimensions

The square is bounded by \(x \in[2,6]\) and \(y \in[5,9]\).

Side length (s): The distance between \(x=6\) and \(x=2\) is 4. Similarly, the distance between \(y=9\) and \(y=5\) is 4.

This confirms the figure is a square of side 4.

Step 3: Find the center of the inscribed circle

The center of a circle inscribed in a square is the midpoint of the square’s boundaries. It sits exactly halfway between the parallel lines.

\(x\)-coordinate of center (\(h\)):

\(

h=\frac{2+6}{2}=\frac{8}{2}=4

\)

\(y\)-coordinate of center \((k)\) :

\(

k=\frac{5+9}{2}=\frac{14}{2}=7

\)

The center of the circle is \((4,7)\).

Example 6: If the centroid of an equilateral triangle is \((2,-2)\) and its one vertex is \((-1,1)\), then the equation of its circumcircle is

(a) \(x^2+y^2-4 x+4 y-10=0\)

(b) \(x^2+y^2+4 x-4 y+10=0\)

(c) \(x^2+y^2+4 x-4 y-10=0\)

(d) \(x^2+y^2-4 x+4 y+10=0\)

Solution: (a) To solve this, we need to recall a key property of equilateral triangles: the centroid and the circumcenter are the exact same point.

Step 1: Identify the Center and Radius

Center \((h, k)\) : Since the centroid is \((2,-2)\), the center of the circumcircle is also \((2,-2)\)

Radius (\(r\)): The circumcircle passes through all vertices of the triangle. Therefore, the distance between the center \((2,-2)\) and the given vertex \((-1,1)\) is the radius.

Calculate \(r^2\) using the distance formula:

\(

\begin{gathered}

r^2=\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2 \\

r^2=(-1-2)^2+(1-(-2))^2 \\

r^2=(-3)^2+(3)^2 \\

r^2=9+9=18

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 2: Write the Equation

Now, we plug the center \((2,-2)\) and \(r^2=18\) into the standard equation \((x-h)^2+(y- k)^2=r^2\) :

\(

(x-2)^2+(y+2)^2=18

\)

\(

x^2+y^2-4 x+4 y-10=0

\)

Example 7: If a point \((\alpha, \beta)\) lies on the circle \(x^2+y^2=1\), then the locus of the point \((3 \alpha+2, \beta)\), is [JEE (Orissa) 2005]

(a) a straight line

(b) an ellipse

(c) a parabola

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) To solve for the locus, we need to find a mathematical relationship between the coordinates of the new moving point.

Step 1: Define the relationship between points

We are given that \((\alpha, \beta)\) lies on the circle \(x^2+y^2=1\). This means:

\(

\alpha^2+\beta^2=1 \dots(1)

\)

Let the new point be \((h, k)\). According to the problem:

\(

\begin{gathered}

h=3 \alpha+2 \\

k=\beta

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 2: Express the original variables in terms of (\(h, k\))

To find the locus, we must substitute \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) into eqn 1. We rearrange the expressions for \(h\) and \(k\) :

From \(h=3 \alpha+2\), we get:

\(

\alpha=\frac{h-2}{3}

\)

From \(k=\beta\), we get:

\(

\beta=k

\)

Step 3: Substitute into the circle equation

Now, substitute these into \(\alpha^2+\beta^2=1\) :

\(

\left(\frac{h-2}{3}\right)^2+k^2=1

\)

Expanding and simplifying (replacing \(h\) with \(x\) and \(k\) with \(y\) for the final locus equation):

\(

\frac{(x-2)^2}{9}+\frac{y^2}{1}=1

\)

Step 4: Identify the curve

The resulting equation is in the standard form of an ellipse:

\(

\frac{(x-h)^2}{a^2}+\frac{(y-k)^2}{b^2}=1

\)

In our case:

The center is \((2,0)\).

The major axis length is \(2 a=2(3)=6\).

The minor axis length is \(2 b=2(1)=2\).

Conclusion: The locus is an ellipse.

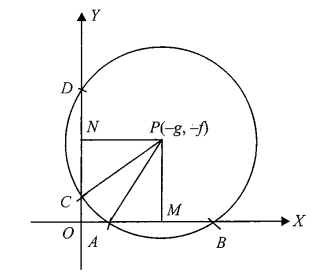

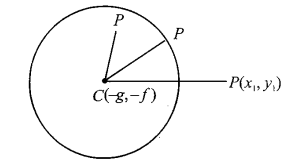

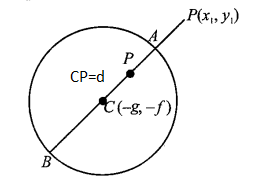

General Equation of a Circle

The general equation of circle is

\(

x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0 \dots(i)

\)

where \(g, f\) and \(c\) are constants.

To find the centre and radius: Eq. (i) can be written as

\(

(x+g)^2+(y+f)^2=\left(\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c}\right)^2

\)

Comparing with the standard equation of circle \((x-h)^2+(y-k)^2=r^2\), We get

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & h=-g, k=-f \\

\text { and } & r=\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c}

\end{array}

\)

∴ \(\quad\) Co-ordinates of the centre are \((-g,-f)\) and radius

\(

=\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c},\left(g^2+f^2 \geq c\right)

\)

Nature of the circle:

Remark-1: Radius of the circle \(x^2+y^2 +2 g x+2 f y+c=0\) is \(\sqrt{\left(g^2+f^2-c\right)}\). Now the following cases are possible:

- If \(g^2+f^2-c>0\), then the radius of circle will be real. Hence in this case, real circle is possible.

- If \(g^2+f^2-c=0\), then the radius of circle will be zero. Hence, in this case circle is called a point circle.

- If \(g^2+f^2-c<0\), then the radius of circle will be imaginary number. Hence, in this case, circle is called a virtual circle or imaginary circle.

Remark-2: The equation \(a x^2+a y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0, a \neq 0\) also represents a circle. This equation can also be written as \(x^2+y^2+\frac{2 g}{a} x+\frac{2 f}{a} y+\frac{c}{a}=0\)

The coordinates of the centre are \(\left(-\frac{g}{a},-\frac{f}{a}\right)\) and, Radius \(=\sqrt{\frac{g^2}{a^2}+\frac{f^2}{a^2}-\frac{c}{a}}\)

Remark-3: A general equation of second degree \(a x^2+2 h x y +b y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0\) in \(x\), \(y\) represent a circle if

- Coefficient of \(x^2=\) coefficient of \(y^2\), i.e. \(a=b\).

- Coefficient of \(x y\) is zero, i.e. \(h=0\).

- \(\Delta=a b c+2 h g f-a f^2-b g^2-c h^2 \neq 0\)

- However for a point circle (whose radius is zero), \(\Delta=0\)

Remark-4: Concentric circles: Two circles having the same centre \(C(h, k)\) but different radii \(r_1\) and \(r_2\), respectively, are called concentric circles. Thus, the circles \((x-h)^2 +(y-k)^2=r_1^2\) and \((x-h)^2+(y-k)^2=r_2^2, r_1 \neq r_2\), are concentric circles. Therefore, the equations of concentric circles differ only in constant terms.

Rule to find the centre and radius of a circle whose equation is given:

- Make the coefficients of \(x^2\) and \(y^2\) equal to 1 and right hand side equal to zero.

- Then co-ordinates of centre will be \((\alpha, \beta)\), where \(\alpha= -\frac{1}{2}\) (coefficient of

- \(x\)) and \(\beta=-\frac{1}{2}\) (coefficient of \(y\)).

- Radius \(=\sqrt{\left(\alpha^2+\beta^2-\text { constant term }\right)}\)

Example 8: If \(g^2+f^2=c\), then the equation \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0\) will represent

(a) a circle of radius \(g\)

(b) a circle of radius \(f\)

(c) a circle of diameter \(\sqrt{c}\)

(d) a circle of radius 0

Solution: (d) The equation represents a circle of radius

\(

\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c}=\sqrt{c-c}=0

\)

Example 9: The equation \(\lambda^2 x^2+\left(\lambda^2-5 \lambda+4\right) x y+(3 \lambda-2) y^2-8 x+12 y-4=0\) will represent a circle, if \(\lambda=\)

(a) 1

(b) 4

(c) 2

(d) none of these

Solution: (a) The given equation will represent a circle, if Coeff. of \(x^2=\) Coeff of \(y^2\) and Coeff. of \(x y=0\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \lambda^2=3 \lambda-2 \text { and } \lambda^2-5 \lambda+4=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \lambda^2-3 \lambda+2=0 \text { and } \lambda^2-5 \lambda+4=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(\lambda-1)(\lambda-2)=0 \text { and }(\lambda-1)(\lambda-4)=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \lambda=1

\end{aligned}

\)

Since the only value appearing in both sets is \(\lambda=1\), is the only answer.

Example 10: The coordinates of the centre and radius of the circle represented by the equation

\((3-2 \lambda) x^2+\lambda y^2-4 x+2 y-4=0 \text { are }\)

(a) \((2,1), 3\)

(b) \((-2,1), 3\)

(c) \((2,-1), 3\)

(d) \((2,-1), 1\)

Solution: (c) The equation \((3-2 \lambda) x^2+\lambda y^2-4 x+2 y-4=0\) will represent a circle if

\(

3-2 \lambda=\lambda \Rightarrow \lambda=1 \quad\left[\because \text { Coeff. of } x^2=\text { Coeff. of } y^2\right]

\)

Putting \(\lambda=1\) in the given equation, we get

\(

x^2+y^2-4 x+2 y-4=0

\)

The coordinates of centre and radius of the circle represented by this equation are \((2,-1)\) and 3 respectively.

Example 11: If \(3 x^2+2 \lambda x y+3 y^2+(6-\lambda) x+(2 \lambda-6) y-21=0\) is the equation of a circle, then its radius is

(a) 1

(b) 3

(c) \(2 \sqrt{2}\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

3 x^2+2 \lambda x y+3 y^2+(6-\lambda) x+(2 \lambda-6) y-21=0 \dots(i)

\)

This equation will represent a circle, if

Coeff. of \(x y=0 \Rightarrow \lambda=0\)

Putting \(\lambda=0\) in (i), we obtain \(x^2+y^2+2 x-2 y-7=0\)

Clearly, it represents a circle of radius \(=\sqrt{1+1+7}=3\).

Example 12: If the area of the circle \(4 x^2+4 y^2-8 x+16 y+k=0\) is \(9 \pi\) square units, then the value of \(k\) is

(a) 4

(b) 16

(c) -16

(d) \(\pm 16\)

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

4 x^2+4 y^2-8 x+16 y+k=0 \Rightarrow x^2+y^2-2 x+4 y+\frac{k}{4}=0

\)

The radius of this circle is \(\sqrt{1+4-\frac{k}{4}}=\frac{\sqrt{20-k}}{2}\)

We have,

Area of the circle \(=9 \pi\) square units

\(

\Rightarrow \quad \pi\left(\frac{20-k}{4}\right)=9 \pi \Rightarrow k=-16

\)

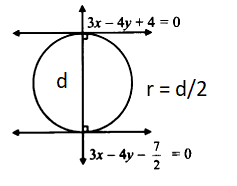

Example 13: If the lines \(3 x-4 y+4=0\) and \(6 x-8 y-7 =0\) are tangents to a circle, then find the radius of the circle.

Solution: To solve this, we first need to look at the relationship between the two lines. Notice the coefficients of \(x\) and \(y\) :

Line 1: \(3 x-4 y+4=0\)

Line 2: \(6 x-8 y-7=0\)

If we divide the second equation by 2 , it becomes \(3 x-4 y-3.5=0\). Since both lines have the same slope (\(m=3 / 4\)), they are parallel lines.

The Geometric Logic:

If two parallel lines are tangents to the same circle, they must lie on opposite sides of the circle. Therefore, the distance between these two lines is equal to the diameter of the circle.

Step-by-Step Calculation:

Step 1: Normalize the equations To use the distance formula between parallel lines, the coefficients of \(x\) and \(y\) must be identical.

\(L_1: 3 x-4 y+4=0\)

\(L_2: 3 x-4 y-\frac{7}{2}=0\)

Step 2: Find the Distance \((d)\) The distance between two parallel lines \(A x+B y+C_1=0\) and \(A x+B y+C_2=0\) is given by the formula:

\(

d=\frac{\left|C_1-C_2\right|}{\sqrt{A^2+B^2}}

\)

Plugging in our values ( \(A=3, B=-4, C_1=4, C_2=-3.5\) ):

\(

\begin{gathered}

d=\frac{|4-(-3.5)|}{\sqrt{3^2+(-4)^2}} \\

d=\frac{|7.5|}{\sqrt{9+16}}=\frac{7.5}{5}=3 / 2

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 3: Find the Radius (\(r\)) Because the two parallel tangents are on opposite sides of the circle, the distance \(d\) between them is the diameter. Therefore:

\(

r=\frac{d}{2}=\frac{1.5}{2}=3 / 4

\)

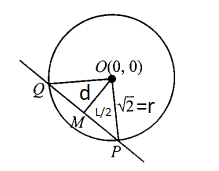

Example 14: Find the length of the chord cut-off by \(y=2 x+1\) from the circle \(x^2+y^2=2\).

Solution: To find the length of the chord cut off by a line from a circle, we can use the geometric relationship between the radius of the circle, the perpendicular distance from the center to the line, and the half-length of the chord.

Step-by-Step Calculation:

Step 1: Identify the circle properties: The given equation is \(x^2+y^2=2\).

The center of the circle is \(O(0,0)\).

The radius is \(r=\sqrt{2}\).

Step 2: Find the perpendicular distance \((d)\) : We need the distance from the center \((0,0)\) to the line \(y=2 x+1\), which can be rewritten as \(2 x-y+1=0\). Using the distance formula \(d=\frac{\left|A x_1+B y_1+C\right|}{\sqrt{A^2+B^2}}\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

d=\frac{|2(0)-(0)+1|}{\sqrt{2^2+(-1)^2}} \\

d=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 3: Calculate the half-length of the chord \((L / 2)\) : In a circle, the perpendicular from the center to a chord bisects the chord, forming a right-angled triangle. By the Pythagorean theorem:

\(

\begin{gathered}

(L / 2)^2=r^2-d^2 \\

(L / 2)^2=(\sqrt{2})^2-\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\right)^2 \\

(L / 2)^2=2-\frac{1}{5}=\frac{9}{5}

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 4: Find the total length of the chord \((L)\) : First, find the half-length by taking the square root:

\(

\frac{L}{2}=\sqrt{\frac{9}{5}}=\frac{3}{\sqrt{5}}

\)

Now, multiply by 2 for the full chord length:

\(

L=\frac{6}{\sqrt{5}}

\)

The length of the chord is \(\frac{6}{\sqrt{5}}\) units.

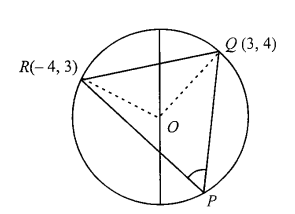

Example 15: An acute triangle \(P Q R\) is inscribed in the circle \(\boldsymbol{x}^{\mathbf{2}}+\boldsymbol{y}^{\mathbf{2}}=\mathbf{2 5}\). If \(\boldsymbol{Q}\) and \(\boldsymbol{R}\) have coordinates \((\mathbf{3}, 4)\) and \((-4,3)\), respectively, then find \(\angle Q P R\).

Solution: Step 1: The Perpendicularity (\(m_1 m_2=-1\))

In coordinate geometry, if the product of the slopes of two lines is -1 , those lines are perpendicular.

Slope of \(O Q\left(m_1\right)=4 / 3\)

Slope of \(O R\left(m_2\right)=-3 / 4\)

\(m_1 \times m_2=(4 / 3) \times(-3 / 4)=-1\)

This proves that the radii \(O Q\) and \(O R\) meet at a right angle ( \(90^{\circ}\) or \(\pi / 2\)) at the center of the circle.

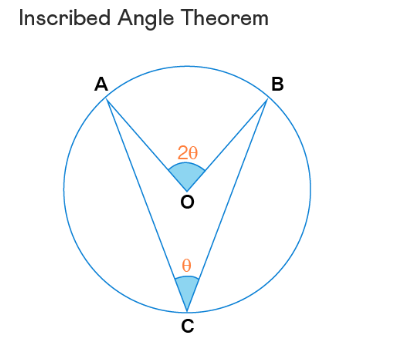

Step 2: The Degree Measure Theorem

There is a fundamental theorem in circle geometry (often called the Inscribed Angle Theorem) which states:

The angle subtended by an arc at the center is double the angle subtended by it at any point on the remaining part of the circle.

Mathematically:

\(

\angle Q O R=2 \angle Q P R

\)

Step 3: Final Calculation

Since you found that \(\angle Q O R=\pi / 2\) (the central angle), you simply divide by 2 to find the inscribed angle at vertex \(P\) :

\(

\angle Q P R=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=\frac{\pi}{4}

\)

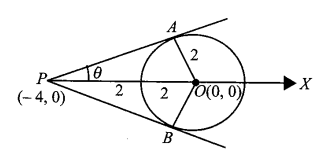

Example 16: Two tangents to the circle \(x^2+y^2=4\) at the points \(A\) and \(B\) meet at \(P(-4,0)\). Then, find the area of the quad rilateral \(P A O B\), where \(O\) is the origin

Solution: To find the area of the quadrilateral \(P A O B\), we can take advantage of the symmetry of the figure. The quadrilateral is composed of two congruent right-angled triangles: \(\triangle P A O\) and \(\triangle P B O\).

Step-by-Step Calculation

Step 1: Identify the properties of the circle: The circle is \(x^2+y^2=4\).

Center \((O):(0,0)\)

Radius \((r): \sqrt{4}=2\)

Step 2: Find the length of the tangents \((L)\) : The distance from the external point \(P(-4,0)\) to the center \(O(0,0)\) is:

\(

O P=\sqrt{(-4-0)^2+(0-0)^2}=4

\)

In the right-angled triangle \(\triangle P A O\) (where the angle at \(A\) is \(90^{\circ}\) because the radius is perpendicular to the tangent):

\(

\begin{gathered}

P A^2+O A^2=O P^2 \\

P A^2+2^2=4^2

\end{gathered}

\)

\(

P A^2=16-4=12 \Longrightarrow P A=\sqrt{12}=2 \sqrt{3}

\)

Step 3: Calculate the area of one triangle: The area of \(\triangle P A O\) is given by:

\(

\begin{gathered}

\text { Area }=\frac{1}{2} \times \text { base × height }=\frac{1}{2} \times P A \times O A \\

\text { Area }=\frac{1}{2} \times 2 \sqrt{3} \times 2=2 \sqrt{3} \text { sq. units }

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 4: Find the total area of quadrilateral \(P A O B\) : Since the quadrilateral is made of two such identical triangles ( \(\triangle P A O\) and \(\triangle P B O\)):

\(

\text { Total Area }=2 \times \text { Area of } \triangle P A O

\)

Total Area \(=2 \times 2 \sqrt{3}=4 \sqrt{3}\) sq. units

Final Answer: The area of the quadrilateral \(P A O B\) is \(4 \sqrt{3}\) square units.

Equation of a Circle Passing Through Three Given Points

The general equation of circle, i.e., \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c =0\) contains three independent constants \(g, f\) and \(c\). Hence, for determining the equation of a circle, three conditions are required. The equation of the circle through three non-collinear points (three non-collinear points are three distinct points that do not lie on the same straight line) \(A\left(x_1, y_1\right), B\left(x_2, y_2\right), C\left(x_3, y_3\right)\) :

Let the equation of circle be

\(

x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0 \dots(i)

\)

If three points \(\left(x_1, y_1\right),\left(x_2, y_2\right),\left(x_3, y_3\right)\) lie on the circle Eq. (i), their coordinates must satisfy its equation. Hence, solving equations

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x_1^2+y_1^2+2 g x_1+2 f y_1+c=0 \dots(ii) \\

& x_2^2+y_2^2+2 g x_2+2 f y_2+c=0 \dots(iii) \\

& x_3^2+y_3^2+2 g x_3+2 f y_3+c=0 \dots(iv)

\end{aligned}

\)

Solving (ii), (iii) and (iv) as simultaneous linear equations in \(g, f\) and \(c\), we can obtain the values of \(g, f\) and \(c\). Substituting these values in (i), we obtain the equation of the desired circle. Alternately, we eliminate \(g, f\) and \(c\) from (i), (ii), (iii) and (iv) to obtain the equation of the required circle as follows:

\(

\left|\begin{array}{cccc}

x^2+y^2 & x & y & 1 \\

x_1^2+y_1^2 & x_1 & y_1 & 1 \\

x_2^2+y_2^2 & x_2 & y_2 & 1 \\

x_3^2+y_3^2 & x_3 & y_3 & 1

\end{array}\right|=0

\)

Remark:

- If \(P\) is a point and \(C\) is the centre of a circle of radius \(r\), then the maximum and minimum distances of \(P\) from the circle are \(C P+r\) and \(C P-r\) respectively.

- Concyclic quadrilateral: If all the four vertices of a quadrilateral lie on a circle, then the quadrilateral is called a cyclic quadrilateral. The four vertices are said to be concyclic. A quadrilateral is cyclic (or concyclic) if all four vertices lie on the circumference of a circle. The sum of the opposite angles is always \(180^{\circ}\) \(

\binom{\angle A+\angle B=180^{\circ}}{\angle C+\angle D=180^{\circ}}

\). Exterior Angles: The measure of an exterior angle at a vertex is equal to the interior opposite angle. Diagonals: The product of the diagonals \((p \times q)\) equals the sum of the products of opposite sides \((a c+b d)\).

Example 17: If a circle passes through the point \((0,0)\), \({(} {a}, {0}),({0}, {b})\), then find its centre.

Solution: Step 1: Substitute the point \((0,0)\) Plug \((0,0)\) into the general equation \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+ 2 f y+c=0\) :

\(

0^2+0^2+2 g(0)+2 f(0)+c=0 \Longrightarrow c=0

\)

Whenever a circle passes through the origin, the constant term \(c\) is always zero.

Step 2: Substitute the point \((a, 0)\) Using \(c=0\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

a^2+0^2+2 g(a)+2 f(0)+0=0 \\

a^2+2 g a=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Since \(a \neq 0\) (otherwise it’s just the origin), we divide by \(a\) :

\(

a+2 g=0 \Longrightarrow g=-\frac{a}{2}

\)

Step 3: Substitute the point \((0, b)\) Using \(c=0\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

0^2+b^2+2 g(0)+2 f(b)+0=0 \\

b^2+2 f b=0 \Longrightarrow f=-\frac{b}{2}

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 4: Identify the centre The centre of the circle in the general form is \((-g,-f)\).

Substituting our values:

\(

\text { Centre }=\left(-\left(-\frac{a}{2}\right),-\left(-\frac{b}{2}\right)\right)=\left(\frac{a}{2}, \frac{b}{2}\right)

\)

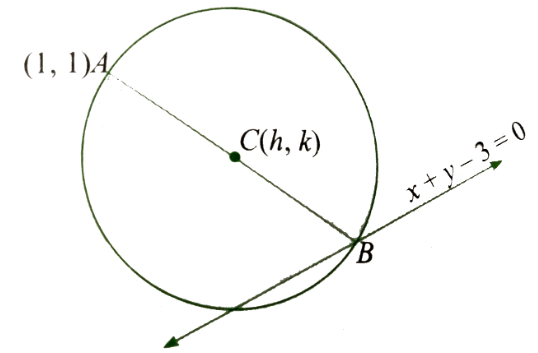

Example 18: Find the equation of circle which passes through the points \((1,-2),(4,-3)\) and whose centre lies on the line \(3 x+4 y=7\).

Solution: Step 1: Set up the general equations Let the equation be \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0\). Since the circle passes through \((1,-2)\) and \((4,-3)\) :

For \((1,-2): 1^2+(-2)^2+2 g(1)+2 f(-2)+c=0 \Longrightarrow 2 g-4 f+c=-5 \dots(1)\)

For \((4,-3): 4^2+(-3)^2+2 g(4)+2 f(-3)+c=0 \Longrightarrow 8 g-6 f+c=-25 \dots(2)\)

Step 2: Eliminate \(c\) to find a relation between \(g\) and \(f\) Subtract (Eqn. 1) from (Eqn. 2):

\(

\begin{gathered}

(8 g-2 g)+(-6 f-(-4 f))+(c-c)=-25-(-5) \\

6 g-2 f=-20 \Longrightarrow 3 g-f=-10 \dots(3)

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 3: Use the center constraint The center of the circle is \((-g,-f)\). The problem states the center lies on the line \(3 x+4 y=7\). Substituting the center coordinates into the line equation:

\(

3(-g)+4(-f)=7 \Longrightarrow-3 g-4 f=7 \dots(4)

\)

Step 4: Solve for \(g\) and \(f\) Add (Eqn. 3) and (Eqn. 4) together:

\(

\begin{gathered}

(3 g-3 g)+(-f-4 f)=-10+7 \\

-5 f=-3 \Longrightarrow f=\frac{3}{5}

\end{gathered}

\)

Now, substitute \(f=\frac{3}{5}\) back into (Eqn. 3):

\(

\begin{gathered}

3 g-\frac{3}{5}=-10 \Longrightarrow 3 g=-10+\frac{3}{5}=-\frac{47}{5} \\

g=-\frac{47}{15}

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 5: Find \(c\) and write the final equation Substitute \(g\) and \(f\) into (Eqn. 1):

\(

\begin{gathered}

2\left(-\frac{47}{15}\right)-4\left(\frac{3}{5}\right)+c=-5 \\

-\frac{94}{15}-\frac{36}{15}+c=-5 \Longrightarrow-\frac{130}{15}+c=-5 \\

c=-5+\frac{26}{3}=\frac{11}{3}

\end{gathered}

\)

Substituting \(g, f, c\) into the general equation:

\(

x^2+y^2+2\left(-\frac{47}{15}\right) x+2\left(\frac{3}{5}\right) y+\frac{11}{3}=0

\)

Multiply by 15 to clear the denominators:

\(

15 x^2+15 y^2-94 x+18 y+55=0

\)

Final Answer: The equation of the circle is \(15 x^2+15 y^2-94 x+18 y+55=0\).

Example 19: Show that a cyclic quadrilateral is formed by the lines \(5 x+3 y=9, x=3 y, 2 x=y\) and \(x+4 y+2=0\) taken in order. Find the equation of the circumcircle.

Solution: Sol. Solving the given equation in pairs taken in order, the coordinates of the vertices of the quadrilateral \(A B C D\) are \(A\left(\frac{3}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\right), B(0,0), C\left(-\frac{2}{9},-\frac{4}{9}\right)\) and \(D\left(\frac{42}{17},-\frac{19}{17}\right)\).

First, we shall find the equation of the circle passing through \(A, B\) and \(C\). Let the equation of this circle be

\(

x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0 \dots(i)

\)

Coordinates of the points \(A, B\) and \(C\) must satisfy Eq. (i), so substituting in Eq. (i), we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

3 g+f+c+\frac{5}{2} & =0 \dots(ii) \\

c & =0 \dots(iii)

\end{aligned}

\)

and \(4 g+8 f-9 c=\frac{20}{9} \dots(iv)\)

Solving Eqs. (ii), (iii) and (iv), we get \(g=-\frac{10}{9}, f=\frac{5}{6}\) and \(c=0\).

Substituting in Eq. (i), the equation of the circle through the vertices \(A, B, C\) is

\(

9 x^2+9 y^2-20 x+15 y=0 \dots(v)

\)

Since the coordinates of the vertex \(D\left(\frac{42}{17},-\frac{19}{17}\right)\) also satisfy Eq. (v), hence a cyclic quadrilateral \(A B C D\) is formed by the given lines, and Eq. (v) is the equation of the circumcircle of the quadrilateral.

Example 20: The straight line \(\frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}=1\) cuts the coordinate axes at \(A\) and \(B\). The equation of the circle passing through \(O(0,0)\), \(A\) and \(B\), is

(a) \(x^2+y^2-a x-b y=0\)

(b) \(x^2+y^2-2 a x-2 b y=0\)

(c) \(x^2+y^2+a x+b y=0\)

(a) \(x^2+y^2=a^2+b^2\)

Solution: (a) Identify the coordinates of A and B The equation of the line is given in intercept form: \(\frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}=1\).

To find the \(x\)-intercept \((A)\), set \(y=0: \frac{x}{a}=1 \Longrightarrow x=a\). So, \(A\) is \((a, 0)\).

To find the \(y\)-intercept \((B)\), set \(x=0\) : \(\frac{y}{b}=1 \Longrightarrow y=b\). So, \(B\) is \((0, b)\).

Let \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0 \dots(i)\)

be the circle passing through \(O, A\) and \(B\). Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

0+c =0 \dots(ii) \\

a^2+2 g a+c =0 \dots(iii) \\

b^2+2 f b+c =0 \dots(iv)

\end{aligned}

\)

Solving (ii), (iii) and (iv), we obtain

\(

g=-\frac{a}{2}, f=-\frac{b}{2} \text { and } c=0

\)

Substituting these values in (i), we obtain the equation of the required circle as \(x^2+y^2-a x-b y=0\)

Example 21: If the points \((0,0),(1,0),(0,1)\) and \((t, t)\) are concyclic, then \(t=\)

(a) -1

(b) 1

(c) 2

(d) -2

Solution: (b) That is another great example of using the intercept shortcut! Since the points \((0,0),(1,0)\), and \((0,1)\) are our reference points, they form that familiar right-angled triangle at the origin with intercepts \(a=1\) and \(b=1\).

Step-by-Step Logic:

Step 1: Identify the circle equation Using the pattern \(x^2+y^2-a x-b y=0\) for \(a=1\) and \(b=1\) :

\(

x^2+y^2-x-y=0

\)

Step 2: Apply the concyclic condition For the point \((t, t)\) to be concyclic (lying on the same circle), it must satisfy the equation:

\(

t^2+t^2-t-t=0

\)

\(

2 t^2-2 t=0

\)

Step 3: Solve for \(t\) Factor out \(2 t\) :

\(

2 t(t-1)=0

\)

This gives us two possibilities:

\(t=0\) : This results in the point \((0,0)\), which we already knew was on the circle.

\(t=1\) : This gives us the point \((1,1)\).

Example 22: The equation of the circle passing through \((1,0)\) and \((0,1)\) and having the smallest possible radius, is [AIEEE 2011]

(a) \(x^2+y^2+x+y-2=0\)

(b) \(x^2+y^2=x+y\)

(c) \(x^2+y^2=1\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) Let the equation of the required circle be

\(

x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0 \dots(i)

\)

This passes through \(A(1,0)\) and \(B(0,1)\). Therefore,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 1+2 g+c=0 \text { and, } 1+2 f+c=0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & g=-\left(\frac{c+1}{2}\right) \text { and, } f=-\left(\frac{c+1}{2}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Let \(r\) be the radius of circle (i). Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

r & =\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c} \\

\Rightarrow \quad r & =\sqrt{\left(\frac{c+1}{2}\right)^2+\left(\frac{c+1}{2}\right)^2-c} \\

\Rightarrow \quad r & =\sqrt{\frac{c^2+1}{2}} \Rightarrow r^2=\frac{1}{2}\left(c^2+1\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Clearly, \(r\) is minimum when \(c=0\) and the minimum value of \(r\) is \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\).

For \(c=0\), we have \(g=-\frac{1}{2}\) and \(f=-\frac{1}{2}\)

Substituting the values of \(g, f\) and \(c\) in (i), we get \(x^2+y^2-x-y=0\) as the equation of the required circle.

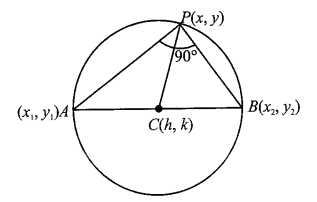

Equation of Circle on a Given Diameter

To derive the equation of a circle when given the endpoints of its diameter, we can use the fundamental property of a circle: any angle subtended by the diameter at the circumference is a right angle \(\left(90^{\circ}\right)\).

Step 1: The Setup

Let the two endpoints of the diameter be:

\(A\left(x_1, y_1\right)\)

\(B\left(x_2, y_2\right)\)

Let \(P(x, y)\) be any arbitrary point on the circumference of the circle.

Step 2: The Geometric Relationship

According to Thales’s Theorem, the angle \(\angle A P B\) is always \(90^{\circ}\) (a right angle). This means that the line segment \(A P\) is perpendicular to the line segment \(B P\).

In coordinate geometry, if two lines are perpendicular, the product of their slopes (\(m_1\) and \(m_2\)) is -1 :

\(

m_{A P} \cdot m_{B P}=-1

\)

Step 3: Calculating the Slopes

We calculate the slope of \(A P\left(m_{A P}\right)\) and the slope of \(B P\left(m_{B P}\right)\) using the coordinates:

Slope of AP: \(m_{A P}=\frac{y-y_1}{x-x_1}\)

Slope of \(B P: m_{B P}=\frac{y-y_2}{x-x_2}\)

Step 4: The Derivation

Now, substitute these slopes into our perpendicularity condition:

\(

\left(\frac{y-y_1}{x-x_1}\right) \cdot\left(\frac{y-y_2}{x-x_2}\right)=-1

\)

Multiply both sides by \(\left(x-x_1\right)\left(x-x_2\right)\) :

\(

\left(y-y_1\right)\left(y-y_2\right)=-\left(x-x_1\right)\left(x-x_2\right)

\)

Rearrange the equation to bring all terms to one side:

\(

\left(x-x_1\right)\left(x-x_2\right)+\left(y-y_1\right)\left(y-y_2\right)=0

\)

The general diameter form of the equation of a circle is:

\(

\left(x-x_1\right)\left(x-x_2\right)+\left(y-y_1\right)\left(y-y_2\right)=0

\)

Remarks

- If the coordinates of the end points of a diameter of a circle are given, we can also find the equation of the circle by finding the coordinates of the centre and radius. The centre is the mid-point of the diameter and radius is half of the length of the diameter.

- The diameter form of a circle can also be written as \(x^2+y^2-x\left(x_1+x_2\right)-y\left(y_1+y_2\right)+x_1 x_2+y_1 y_2=0\) or \(x^2+y^2-x\) (Sum of the abscissae) \(-y\) (Sum of the ordinates) + Product of the abscissae + Product of the ordinates \(=0\).

Example 23: The equation \(\left(x-x_1\right)\left(x-x_2\right)+\left(y-y_1\right)\left(y-y_2\right)=0\) represents a circle whose centre is [JEE (WB) 2008]

(a) \(\left(\frac{x_1-x_2}{2}, \frac{y_1-y_2}{2}\right)\)

(b) \(\left(\frac{x_1+x_2}{2}, \frac{y_1+y_2}{2}\right)\).

(c) \(\left(x_1, y_2\right)\)

(d) \(\left(x_2, y_2\right)\)

Solution: (b) Since \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and \(\left(x_2, y_2\right)\) are the endpoints of the diameter, the center of the circle must be the midpoint of that segment.

To find the center, we use the midpoint formula:

Step 1: Identify the Midpoint Formula: The center \(C(h, k)\) of a line segment between two points is the average of their coordinates.

Step 2: Calculate the x-coordinate: \(h=\frac{x_1+x_2}{2}\)

Step 3: Calculate the \({y}\)-coordinate: \(k=\frac{y_1+y_2}{2}\)

Step 4: Combine for the Center: \(C=\left(\frac{x_1+x_2}{2}, \frac{y_1+y_2}{2}\right)\)

Verification via Expansion:

If we expand the diameter form equation:

\(

x^2-\left(x_1+x_2\right) x+x_1 x_2+y^2-\left(y_1+y_2\right) y+y_1 y_2=0

\)

In the general equation of a circle \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0\), the center is given by (\(-g,-f\)). Comparing the terms:

\(2 g=-\left(x_1+x_2\right) \Longrightarrow-g=\frac{x_1+x_2}{2}\)

\(2 f=-\left(y_1+y_2\right) \Longrightarrow-f=\frac{y_1+y_2}{2}\)

Example 24: Find the equation of the circle which passes through \((1,0)\) and \((0,1)\) and has its radius as small as possible.

Solution: To find the equation of a circle passing through two points with the minimum possible radius, the line segment connecting those two points must be the diameter of the circle.

If the segment were not the diameter (i.e., a chord), the center would be further away from the segment, resulting in a larger radius.

The Setup

Point \(A\left(x_1, y_1\right):(1,0)\)

Point \(B\left(x_2, y_2\right):(0,1)\)

The Step-by-Step Calculation

Step 1: Identify the Diameter Form: Use the formula derived earlier for a circle with a given diameter:

\(

\left(x-x_1\right)\left(x-x_2\right)+\left(y-y_1\right)\left(y-y_2\right)=0

\)

Step 2: Substitute the Coordinates: Plug in \(x_1=1, y_1=0\) and \(x_2=0, y_2=1\) :

\(

(x-1)(x-0)+(y-0)(y-1)=0

\)

Step 3: Expand the Terms: Multiply the binomials:

\(

\left(x^2-x\right)+\left(y^2-y\right)=0

\)

Step 4: Final Equation: Rearrange into the standard general form:

\(

x^2+y^2-x-y=0

\)

Explanation: To minimize the radius of a circle passing through two points \({A}\) and \({B}\), the segment \(A B\) must be the diameter because the minimum radius is half the distance between the points \(\left(\frac{d(A, B)}{2}\right)\). If \(A B\) is a chord rather than a diameter, the center must lie on the perpendicular bisector of \(A B\), forcing it further from the chord, which increases the radius.

Example 25: If the abscissa and ordinates of two points \(P\) and \(Q\) are the roots of the equations \(x^2+2 a x-b^2=0\) and \(x^2+2 p x-q^2=0\), respectively, then find the equation of the circle with \(P Q\) as diameter.

Solution: Let \(x_1, x_2\) and \(y_1, y_2\) be roots of \(x^2+2 a x-b^2=0\) and \(x^2+2 p x-q^2=0\), respectively.

Then, \(x_1+x_2=-2 a, x_1 x_2=-b^2\)

and \(y_1+y_2=-2 p, y_1 y_2=-q^2\)

The equation of the circle with \(P\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and \(Q\left(x_2, y_2\right)\) as the end points of diameter is

\(

\begin{aligned}

& & \left(x-x_1\right)\left(x-x_2\right)+\left(y-y_1\right)\left(y-y_2\right) & =0 \\

\Rightarrow & & x^2+y^2-x\left(x_1+x_2\right)-y\left(y_1+y_2\right)+x_1 x_2+y_1 y_2 & =0 \\

\Rightarrow & & x^2+y^2+2 a x+2 p y-b^2-q^2 & =0

\end{aligned}

\)

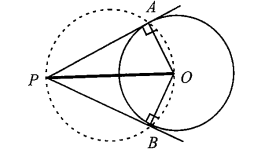

Example 26: Tangents \(P A\) and \(P B\) are drawn to \(x^2+y^2=a^2\) from the point \(P\left(x_1, y_1\right)\). Then find the equation of the circumcircle of triangle \(P A B\).

Solution: To solve this, we use a beautiful property of tangents and circles: the points \(P, A, O\) (the origin), and \(B\) are concyclic. (In geometry, a set of points are said to be concyclic if they all lie on a single common circle.)

Since \(P A\) and \(P B\) are tangents to the circle \(x^2+y^2=a^2\) at points \(A\) and \(B\), the radii \(O A\) and \(O B\) are perpendicular to the tangents. This means \(\angle O A P=90^{\circ}\) and \(\angle O B P=90^{\circ}\).

The Geometric Logic

Step 1: Identify the Right Angles: In \(\triangle O A P\) and \(\triangle O B P\), the angles at \(A\) and \(B\) are \(90^{\circ}\).

Step 2: Recognize the Cyclic Quadrilateral: Because the opposite angles \(\angle O A P\) and \(\angle O B P\) sum to \(180^{\circ}\), the quadrilateral \(O A P B\) is cyclic.

Step 3: Identify the Diameter: In the circumcircle of \(\triangle P A B\) (which is the same as the circumcircle of quadrilateral \(O A P B\)), the segment \(O P\) must be the diameter. Why? Because it subtends a \(90^{\circ}\) angle at points \(A\) and \(B\).

Step 4: Locate the Endpoints: The endpoints of this diameter are:

Origin \(O(0,0)\)

Point \(P\left(x_1, y_1\right)\)

The Equation Calculation

Step 5: Apply Diameter Form: Use the diameter form \(\left(x-x_1\right)\left(x-x_2\right)+(y- \left.y_1\right)\left(y-y_2\right)=0\) with coordinates \((0,0)\) and \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) :

\(

(x-0)\left(x-x_1\right)+(y-0)\left(y-y_1\right)=0

\)

The equation of the circumcircle of \(\triangle P A B\) is:

\(

x^2+y^2-x_1 x-y_1 y=0

\)

Example 27: The locus of the centres of the circles for which one end of a diameter is \((1,1)\) while the other end is on the line \(x+y=3\), is

(a) \(x+y=1\)

(b) \(2(x-y)=5\)

(c) \(2 x+2 y=5\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) To solve this, we use the midpoint property of a circle’s center relative to its diameter.

Fixed point (one end of diameter): \(A(1,1)\)

Moving point (other end of diameter): \(B\left(x_2, y_2\right)\)

Constraint for B: Since \(B\) lies on the line \(x+y=3\), its coordinates must satisfy the equation:

\(

x_2+y_2=3

\)

The Center: Let the center of the circle be \(C(h, k)\).

Step 1: Apply the Midpoint Formula: The center \(C(h, k)\) is the midpoint of diameter \(A B\)

\(

h=\frac{1+x_2}{2} \quad \text { and } \quad k=\frac{1+y_2}{2}

\)

Step 2: Express the moving point in terms of the center: Rearrange the equations from Step 1 to solve for \(x_2\) and \(y_2\) :

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x_2=2 h-1 \\

& y_2=2 k-1

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 3: Substitute into the line equation: We know \(B\left(x_2, y_2\right)\) lies on \(x+y=3\).

Substitute the expressions from Step 2:

\(

(2 h-1)+(2 k-1)=3

\)

Step 4: Simplify the equation:

\(

\begin{gathered}

2 h+2 k-2=3 \\

2 h+2 k=5

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 5: Generalize the Locus: Replace \((h, k)\) with \((x, y)\) to find the general equation:

\(

2 x+2 y=5

\)

The locus of the center \((h, k)\) is the line \(2 x+2 y=5\).

Geometric Insight: The locus of the midpoint of a segment where one end is fixed and the other moves along a line is always another line parallel to the original line. A locus (plural: loci) is simply the set of all points that satisfy a specific rule or condition.

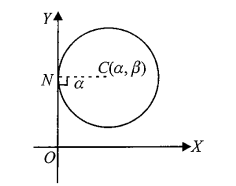

Parametric Form of Circle

The parametric coordinates of any point on the circle \((x-h)^2+(y-k)^2=r^2\) are given by \((h+r \cos \theta, k+r \sin \theta\)), where \(\theta\) is parameter (\(0 \leq \theta \leq 2 \pi[latex]).

As from Figure above, [latex]\cos \theta=\frac{Q M}{P Q}=\frac{x-h}{r}[latex] and [latex]\sin \theta=\frac{P M}{P Q}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =\frac{y-k}{r} \\

& \Rightarrow x=h+r \cos \theta \text { and } y=k+r \sin \theta

\end{aligned}

\)

Remarks

- In particular, coordinates of any point on the circle \(x^2+y^2=r^2\) are \((r \cos \theta, r \sin \theta)(0 \leq \theta<2 \pi)\).

- The parametric coordinates of any point on the circle \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0\) are \(x=-g+\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c} \cos \theta\) and \(y=-f+\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c} \sin \theta(0 \leq \theta<2 \pi)\).

Example 28: \(\alpha, \beta\) and \(\gamma\) are the parametric angles of three points \(P, Q\), and \(R\) respectively, on the circle \(x^2+y^2=1\), and \(A\) is the point \((-1,0)\). If the lengths of the chords \(A P, A Q\) and \(A R\) are in \(G P\), then \(\cos \alpha / 2, \cos \beta / 2\) and \(\cos \gamma / 2\) are in

(a) \(A P\)

(b) \(G P\)

(c) \(H P\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) Let \(P(\cos \alpha, \sin \alpha), Q(\cos \beta, \sin \beta)\) and \(R(\cos \gamma, \sin \gamma)\) be three specified points on the given circle.

\(

\begin{aligned}

A P & =\sqrt{(-1-\cos \alpha)^2+(0-\sin \alpha)^2} \\

\Rightarrow \quad A P & =\sqrt{2+2 \cos \alpha}=\sqrt{4 \cos ^2 \alpha / 2}=2 \cos \alpha / 2

\end{aligned}

\)

Similarly, we have

\(

A Q=2 \cos \beta / 2 \text { and } A R=2 \cos \gamma / 2 \text {. }

\)

Relate to Geometric Progression (GP): If \(A P, A Q, A R\) are in GP, then:

\(

\left(2 \cos \frac{\beta}{2}\right)^2=\left(2 \cos \frac{\alpha}{2}\right) \cdot\left(2 \cos \frac{\gamma}{2}\right)

\)

Divide both sides by 4 :

\(

\cos ^2 \frac{\beta}{2}=\cos \frac{\alpha}{2} \cdot \cos \frac{\gamma}{2}

\)

By definition, if the square of a middle term equals the product of the two outer terms (\(b^2= a c\)), the terms are in a Geometric Progression.

Therefore, \(\cos \frac{\alpha}{2}, \cos \frac{\beta}{2}\), and \(\cos \frac{\gamma}{2}\) are in GP.

Example 29: The centre of the circle \(x=2+3 \cos \theta\), \(y=3 \sin \theta-1\), is

(a) \((3,3)\)

(b) \((2,-1)\)

(c) \((-2,1)\)

(d) \((-1,2)\)

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

x=2+3 \cos \theta \text { and } y=3 \sin \theta-1 \Rightarrow(x-2)^2+(y+1)^2=3^2

\)

Clearly, it is the equation of a circle having its centre at \((2,-1)\).

Example 30: Find the parametric form of the equation of the circle \(x^2+y^2+p x+p y=0\).

Solution: To find the parametric form, we first need to convert the general equation into the standard form \((x-h)^2+(y-k)^2=r^2\) to identify the center \((h, k)\) and the radius \(r\).

Convert to Standard Form:

The given equation is \(x^2+y^2+p x+p y=0\). We will use the method of completing the square:

Step 1: Group the \(x\) and \(y\) terms:

\(

\left(x^2+p x\right)+\left(y^2+p y\right)=0

\)

Step 2: Complete the square for both: To complete the square for \(x^2+p x\), add \(\left(\frac{p}{2}\right)^2\).

Do the same for \(y\).

\(

\left(x^2+p x+\frac{p^2}{4}\right)+\left(y^2+p y+\frac{p^2}{4}\right)=\frac{p^2}{4}+\frac{p^2}{4}

\)

Step 3: Simplify into squares:

\(

\begin{gathered}

\left(x+\frac{p}{2}\right)^2+\left(y+\frac{p}{2}\right)^2=\frac{2 p^2}{4} \\

\left(x+\frac{p}{2}\right)^2+\left(y+\frac{p}{2}\right)^2=\left(\frac{p}{\sqrt{2}}\right)^2

\end{gathered}

\)

Identify Center and Radius:

From the standard form, we can see:

Center \((h, k):\left(-\frac{p}{2},-\frac{p}{2}\right)\)

Radius \(r: \frac{p}{\sqrt{2}}\)

Write the Parametric Equations:

The general parametric form for any circle is:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=h+r \cos \theta \\

& y=k+r \sin \theta

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 4: Substitute the values:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=-\frac{p}{2}+\frac{p}{\sqrt{2}} \cos \theta \\

& y=-\frac{p}{2}+\frac{p}{\sqrt{2}} \sin \theta

\end{aligned}

\)

The parametric form of the equation is:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=\frac{p}{2}(\sqrt{2} \cos \theta-1) \\

& y=\frac{p}{2}(\sqrt{2} \sin \theta-1)

\end{aligned}

\)

(Where \(0 \leq \theta<2 \pi\))

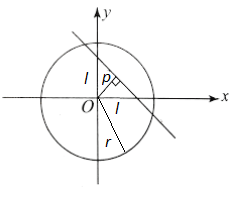

Intercepts Made on the Axes by a Circle

The lengths of intercepts made by the circle \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y +c=0\) with \(X\) and \(Y\) axes are \(2 \sqrt{g^2-c}\) and \(2 \sqrt{f^2-c}\) respectively.

Derivation: From the diagram \(P M=|f|\) and \(P N=|g|\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { Also } A P=C P, \text { radius }=\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c} \\

& \therefore \quad A B=2 A M=2 \sqrt{A P^2-P M^2} \\

& =2 \sqrt{\left(g^2+f^2-c\right)-f^2}=2 \sqrt{g^2-c}

\end{aligned}

\)

Similarly, \(C D=2 \sqrt{f^2-c}\)

Remarks

- Intercepts are always positive.

- If circle touches \(x\)-axis then \(|A B|=0 \therefore c=g^2\) and if circle touches \(y\)-axis then \(|C D|=0 \therefore c=f^2\).

- If circle touches both axes, then \(|A B|=0=|C D| \therefore c=g^2=f^2\).

Example 31: Find the length of intercept, the circle \(x^2+y^2+10 x-6 y+9=0\) makes on the \(x\)-axis.

Solution: Comparing the given equation with \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\therefore \text { Length of intercept on } x \text {-axis } & =2 \sqrt{g^2-c} \\

& =2 \sqrt{(5)^2-9}=8

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 32: If the intercepts of the variable circle on the \(x\)-axis and \(y\)-axis are 2 units 4 units respectively, then find the locus of the centre of the variable circle.

Solution:

\(

\begin{array}{rlrl}

\text { Given that } & 2 \sqrt{g^2-c} =2 \text { and } 2 \sqrt{f^2-c}=4 \\

\Rightarrow & g^2-c =1 \text { and } f^2-c=4 \\

\Rightarrow & \text { Hence, locus is } f^2-g^2 & =3 \\

y^2-x^2 & =3 .

\end{array}

\)

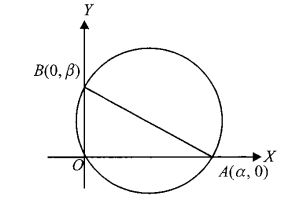

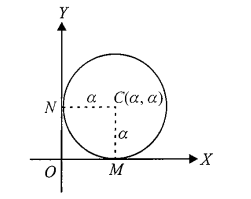

Different forms of the Equations of a Circle

Case-I: When the circle passes through the origin \((0,0)\) and has intercepts \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) on the \(\boldsymbol{x}\)-axis and \(\boldsymbol{y}\)-axis, respectively:

Clearly, \(A\) and \(B\) are end points of diameter.

Hence, equation of circle is

\(

\begin{aligned}

(x-\alpha)(x-0)+(y-0)(y-\beta) & =0 \\

\text { or } \quad x^2+y^2-\alpha x-\beta y & =0

\end{aligned}

\)

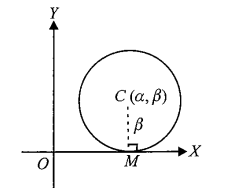

Case-II: When the circle touches \(x\)-axis:

(x-\alpha)^2+(y-\beta)^2=\beta^2

\)

Case-III: When the circle touches \(y\)-axis:

(x-\alpha)^2+(y-\beta)^2=\alpha^2

\)

Case-IV: When the circle touches both axes:

(x-\alpha)^2+(y-\alpha)^2=\alpha^2

\)

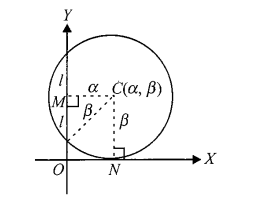

Case-V: When the circle touches \(x\)-axis at \((\alpha, 0)\) and cuts off intercept on \(y\)-axis of length \(2 l\) :

From the figure, \(\beta=\sqrt{\alpha^2+l^2}\)

Hence, equation of circle is \((x-\alpha)^2+(y-\beta)^2=\beta^2\).

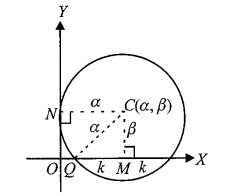

Case-VI: When the circle touches \(y\)-axis at \((0, \beta)\) and cuts off intercept on \(x\)-axis of length \(2 k\) :

From the figure, \(\alpha=\sqrt{\beta^2+k^2}\)

Hence, equation of circle is \((x-\alpha)^2+(y-\beta)^2=\alpha^2\).

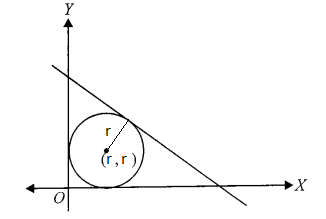

Example 33: Find the equation of the circle which touches both the axes and the straight line \(4 x+3 y=6\) in the first quadrant and lies below it.

Solution: This is a classic problem where we use the properties of a circle’s center and its distance from lines. Since the circle touches both axes in the first quadrant, its center must be equidistant from both axes.

The Setup:

Center \((h, k)\) : Because the circle touches the \(x\)-axis and \(y\)-axis in the first quadrant, \(h=k=r\). So, the center is \((r, r)\).

Radius: \(r\)

The Line: \(4 x+3 y-6=0\)

The Step-by-Step Derivation:

Step 1: Use the Perpendicular Distance Formula: The distance from the center \((r, r)\) to the line \(4 x+3 y-6=0\) must be equal to the radius \(r\).

\(

\text { Distance }=\frac{\left|a x_1+b y_1+c\right|}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2}}

\)

Step 2: Substitute the values:

\(

\begin{gathered}

r=\frac{|4(r)+3(r)-6|}{\sqrt{4^2+3^2}} \\

r=\frac{|7 r-6|}{5}

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 3: Solve the Absolute Value Equation: Multiply by 5 and remove the absolute value signs (considering the “below the line” condition):

\(

5 r=|7 r-6|

\)

This gives two possibilities:

\(5 r=7 r-6 \Longrightarrow 2 r=6 \Longrightarrow r=3\)

\(5 r=-(7 r-6) \Longrightarrow 5 r=-7 r+6 \Longrightarrow 12 r=6 \Longrightarrow r=0.5\)

Step 4: Select the correct radius: The problem states the circle lies below the line. Let’s check the position of the origin \((0,0)\) relative to the line \(4 x+3 y-6=0\). Since \(4(0)+ 3(0)-6=-6\) (negative), “below” the line corresponds to the side where the expression \(4 x+3 y-6\) is negative.

For \(r=3: 4(3)+3(3)-6=15\) (Positive-this circle is above/further from origin).

For \(r=0.5: 4(0.5)+3(0.5)-6=2+1.5-6=-2.5\) (Negative-this circle is below).

Therefore, \(r=0.5\).

Final Equation:

Substitute \(r=0.5\) (or \(1 / 2\) ) into the standard circle equation \((x-r)^2+(y-r)^2=r^2\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

(x-0.5)^2+(y-0.5)^2=(0.5)^2 \\

x^2-x+0.25+y^2-y+0.25=0.25 \\

x^2+y^2-x-y+0.25=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Multiplying by \(\mathbf{4}\) to clear decimals:

\(

4 x^2+4 y^2-4 x-4 y+1=0

\)

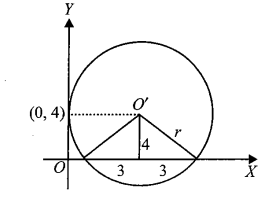

Example 34: A circle touches the \(y\)-axis at the point \((0,4)\) and cuts the \(x\)-axis in a chord of length 6 units. Then find the radius of the circle.

Solution: \(O^{\prime}\) is centre and from the figure given below,

\(

\text { Radius }(r)=\sqrt{(4)^2+(3)^2}=5

\)

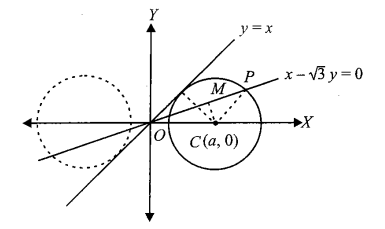

Example 35: Find the equation of the circle which is touched by \(y=x\), has its centre on the positive direction of the \(x\)-axis and cuts off a chord of length 2 units along the line \(\sqrt{3} y-x=0\).

Solution: To solve this, we need to find the radius \(r\) and the center ( \(a, 0\) ) of the circle. Since the center lies on the positive \(x\)-axis, we know the \(y\)-coordinate is 0.

The Setup:

Center: \(C(a, 0)\), where \(a>0\).

Radius: \(r\).

Tangent Line: \(y=x\), which can be written as \(x-y=0\).

Chord Line: \(\sqrt{3} y-x=0\), which can be written as \(x-\sqrt{3} y=0\).

The Step-by-Step Derivation

Step 1: Use the Tangency Condition: The perpendicular distance from the center (\(a, 0\)) to the tangent line \(x-y=0\) must equal the radius \(r\).

\(

r=\frac{|1(a)-1(0)|}{\sqrt{1^2+(-1)^2}}=\frac{a}{\sqrt{2}}

\)

Squaring both sides: \(r^2=\frac{a^2}{2}\)

The circle cuts off a chord of length 2 units along \(x-\sqrt{3} y=0\).

From diagram,

\(

\begin{aligned}

C P^2 & =C M^2+M P^2 \\

\left(\frac{a}{\sqrt{2}}\right)^2 & =\left(\frac{a-\sqrt{3} \times 0}{\sqrt{1^2+(\sqrt{3})^2}}\right)^2+1^2 \\

\Rightarrow \quad \frac{a^2}{2} & =1+\frac{a^2}{4} \Rightarrow a=2

\end{aligned}

\)

Substitute the center \((2,0)\) and \(r^2=2\) into the standard circle equation \((x-h)^2+(y- k)^2=r^2:\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (x-2)^2+(y-0)^2=2 \\

& x^2-4 x+4+y^2=2 \\

& x^2+y^2-4 x+2=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Position of a Point with respect to Circle

In coordinate geometry, we often represent the circle equation as \(S=0\). When you plug a specific point \(P\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) into that equation, the resulting value is denoted as \(S_1\).

Assuming the circle is \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0\) with center \(C(-g,-f)\) and radius \(r=\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c}:\)

\(

\begin{array}{lll}

\text { Condition } & \text { Geometric Meaning } & \text { Position of Point } P \\

S_1>0 & \text { Distance } C P>r & \text { Outside the circle } \\

S_1=0 & \text { Distance } C P=r & \text { On the circumference } \\

S_1<0 & \text { Distance } C P<r & \text { Inside the circle }

\end{array}

\)

Example 36: The set of values of ‘ \(a\) ‘ for which the point \((a-1, a+1)\) lies outside the circle \(x^2+y^2=8\) and inside the circle \(x^2+y^2-12 x+12 y-62=0\), is

(a) \((-\infty,-\sqrt{3}) \cup(\sqrt{3}, \infty)\)

(b) \((-3 \sqrt{2}, 3 \sqrt{2})\)

(c) \((-3 \sqrt{2},-\sqrt{3}) \cup(\sqrt{3}, 3 \sqrt{2})\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) It is given that the point \((a-1, a+1)\) lies outside the circle \(x^2+y^2=8\) and inside the circle \(x^2+y^2-12 x+12 y-62=0\). Therefore,

\(

(a-1)^2+(a+1)^2-8>0

\)

and, \((a-1)^2+(a+1)^2-12(a-1)+12(a+1)-62<0\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad 2 a^2-6>0\) and \(2 a^2-36<0\)

\(\Rightarrow a^2-3>0\) and \(a^2-18<0\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad a \in(-\infty,-\sqrt{3}) \cup(\sqrt{3}, \infty)\) and \(a \in(-3 \sqrt{2}, 3 \sqrt{2})\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad a \in(-3 \sqrt{2},-\sqrt{3}) \cup(\sqrt{3}, 3 \sqrt{2})\)

Maximum and Minimum Distance of a Point from the Circle

Let any point \(P\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and circle \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0\)

The centre and radius of the circle are \((-g,-f)\) and \(\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c}\), respectively.

To find the maximum and minimum distances, you must look at the line segment connecting the point \(P\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and the center \(C(-g,-f)\). Let \(d\) be the distance between these two points (\(d=C P\)):

\(

d=\sqrt{\left(x_1+g\right)^2+\left(y_1+f\right)^2}

\)

The “shortest” and “longest” paths to the circle always lie along the line \(P C\) and its intersection with the circumference.

Case 1: Point \(P\) is Outside the Circle ( \(d>r\) )

When the point is outside, the closest point on the circle is on the near side of the circumference, and the farthest point is on the opposite side.

Minimum Distance: \(d-r\)

Maximum Distance: \(d+r\)

Case 2: Point \(P\) is Inside the Circle (\(d<r\))

If the point is inside, the “minimum” distance is the path to the closest wall of the circle, and the “maximum” is the path to the far wall.

Minimum Distance: \(r-d\)

Maximum Distance: \(r+d\)

Case 3: Point \(P\) is On the Circle (\(d=r\))

Minimum Distance: 0

Maximum Distance: \(2 r\) (the diameter)

Example 37: Find the greatest distance of the point \(P(10,7)\) from the circle \(x^2+y^2-4 x-2 y-20=0\).

Solution: Step 1: Identify Circle Parameters Compare \(x^2+y^2-4 x-2 y-20=0\) to the general form \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0\).

\(2 g=-4 \Longrightarrow g=-2\)

\(2 f=-2 \Longrightarrow f=-1\)

\(c=-20\)

Center \((C):(-g,-f)=(2,1)\) Radius \((r): \sqrt{g^2+f^2-c}= \sqrt{(-2)^2+(-1)^2-(-20)}=\sqrt{25}=5\)

Step 2: Calculate the distance from the point to the center Find the distance \(d\) between the center \(C(2,1)\) and point \(P(10,7)\) using the distance formula:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& d=\sqrt{(10-2)^2+(7-1)^2} \\

& d=\sqrt{8^2+6^2}=\sqrt{100}=10

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 3: Determine the greatest distance Since the point \(P\) is outside the circle (\(d>r\)), the greatest distance is found by traveling from the point, through the center, to the far side of the circumference.

Greatest Distance \(=d+r\)

Greatest Distance \(=10+5=15\) units.

Example 38: Find the number of points \((x, y)\) having integral coordinates satisfying the condition \(x^2+y^2<25\).

Solution: Since \(x^2+y^2<25\) and \(x\) and \(y\) are integers, the possible values of \(x\) and \(y\) are :\{-4,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,4\}[/latex].

Thus, \(x\) and \(y\) can be chosen in nine ways each and \((x, y)\) can be chosen in \(9 \times 9=81\) ways.

However, we have to exclude cases \(( \pm 3, \pm 4),( \pm 4, \pm 3)\) and \(( \pm 4, \pm 4)\), i.e., \(3 \times 4=12\) cases (as these points lies either on the circle or outside circle).

Hence, the number of points are \(81-12=69\).

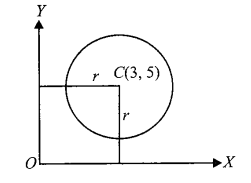

Example 39: The circle \(x^2+y^2-6 x-10 y+k=0\) does not touch or intersect the coordinate axes, and the point (1, 4) is inside the circle. Find the range of the values of \(k\).

Solution: This problem requires us to satisfy three distinct conditions simultaneously. We need to find the range of \(k\) such that the circle avoids both axes and contains the point \((1,4)\).

Step 1: Analyze the circle’s properties The given equation is \(x^2+y^2-6 x-10 y+ k=0\). Comparing this to \(x^2+y^2+2 g x+2 f y+c=0\) :

\(g=-3, f=-5, c=k\)

Center \((C):(3,5)\)

Radius (\(r\)) : \(\sqrt{g^2+f^2-c}=\sqrt{9+25-k}=\sqrt{34-k}\)

For the circle to exist, the radius must be real: \(34-k>0 \Longrightarrow {k}<34\)

Step 2: Condition for not touching or intersecting the axes For a circle to avoid the coordinate axes, its distance from the center to each axis must be greater than its radius.

Distance to \(y\)-axis: The \(x\)-coordinate of the center is 3 . So, \(r<3. \sqrt{34-k}<3 \Longrightarrow 34-k<9 \Longrightarrow {k}>25\)

Distance to \(x\)-axis: The \(y\)-coordinate of the center is 5. So, \(r<5. \sqrt{34-k}<{5} \Longrightarrow 34-k<25 \Longrightarrow {k}>{9}\)

To satisfy both, we must have \(k>25\).

Step 3: Condition for point \((1,4)\) being inside the circle As we discussed earlier, for a point to be inside, \(S_1<0\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

(1)^2+(4)^2-6(1)-10(4)+k<0 \\

1+16-6-40+k<0 \\

-29+k<0 \Longrightarrow {k}<{2 9}

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 4: Combine all constraints We now look for the intersection of all obtained ranges for \(k\) :

\(k<34\) (Existence)

\(k>25\) (Avoiding axes)

\(k<29\) (Point inside)

The overlap of \(25<k<34\) and \(k<29\) gives:

\(

25<k<29

\)

The range of values for \(k\) is \((25,29)\).

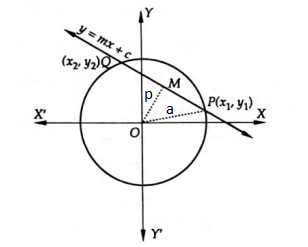

Intersection of a Line and a Circle

Let the equation of the circle be

\(

x^2+y^2=a^2 \dots(i)

\)

and the equation of the line be

\(

y=m x+c \dots(ii)

\)

Solving Eqs. (i) and (ii),

\(

\begin{aligned}

x^2+(m x+c)^2 =a^2 \\

\text { or }\left(1+m^2\right) x^2+2 m c x+c^2-a^2 =0 \dots(iii)

\end{aligned}

\)

To determine the nature of the intersection, we look at the Discriminant (\(D\)) of your quadratic equation:

\(

D=B^2-4 A C

\)

Solution Steps

Step 1: Identify the Discriminant components From your equation \(\left(1+m^2\right) x^2+ 2 m c x+\left(c^2-a^2\right)=0\) :

\(A=\left(1+m^2\right)\)

\(B=2 m c\)

\(C=\left(c^2-a^2\right)\)

Substituting these into the discriminant formula:

\(

\begin{gathered}

D=(2 m c)^2-4\left(1+m^2\right)\left(c^2-a^2\right) \\

D=4 m^2 c^2-4\left(c^2-a^2+m^2 c^2-m^2 a^2\right) \\

D=4\left(a^2+m^2 a^2-c^2\right) \\

D=4 a^2\left(1+m^2\right)-4 c^2

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 2: Analyze the conditions for intersection The line will intersect, touch, or miss the circle based on the sign of \(D\) :

\(

\begin{array}{lll}

\text { Condition } & \text { Result } & \text { Geometric Interpretation } \\

c^2<a^2\left(1+m^2\right) & D>0 & \text { Two real and distinct points (Secant line) } \\

c^2=a^2\left(1+m^2\right) & D=0 & \text { Two coincident points (Tangent line) } \\

c^2>a^2\left(1+m^2\right) & D<0 & \text { No real points (Line lies outside) }

\end{array}

\)

Step 3: Determine the Condition of Tangency The most important result from this derivation is when the line just touches the circle. Setting \(D=0\) gives us the “Condition of Tangency”:

\(

c= \pm a \sqrt{1+m^2}

\)

If this condition is met, the line \(y=m x+c\) is a tangent to the circle \(x^2+y^2=a^2\).

Length of the Chord: If the line is a secant \((D>0)\), the length of the chord intercepted by the circle can be calculated using:

\(

\text { Length }=2 \sqrt{a^2-p^2} [P Q=2 P M=2 \sqrt{O P^2-O M^2}]

\)

(where \(p\) is the perpendicular distance from the center \((0,0)\) to the line \(m x-y+c=0\)).

Example 40: Find the range of values of \(m\) for which the line \(y=m x+2\) cuts the circle \(x^2+y^2=1\) at distinct or coincident points.

Solution: (Perpendicular Distance): For a line to intersect or touch a circle, the perpendicular distance \((p)\) from the center \((0,0)\) to the line \(m x-y+2=0\) must be less than or equal to the radius \((r=1)\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

\frac{|m(0)-(0)+2|}{\sqrt{m^2+(-1)^2}} \leq 1 \Longrightarrow \frac{2}{\sqrt{m^2+1}} \leq 1 \\

2 \leq \sqrt{m^2+1} \Longrightarrow 4 \leq m^2+1 \Longrightarrow m^2 \geq 3

\end{gathered}

\)

The range of values for \(m\) is \((-\infty,-\sqrt{3}] \cup[\sqrt{3}, \infty)\).

Example 41: If the line \(y=m x\) does not intersect the circle \((x+10)^2+(y+10)^2=180\), then

(a) \(m \in(-2, \infty)\)

(b) \(m \in(-\infty,-1 / 2)\)

(c) \(m \in(-2,-1 / 2)\)

(d) none of these.

Solution: (c) The line \(y=m x\) will not intersect the circle \((x+10)^2+(y+10)^2=180\), if

Length of perpendicular from the centre \(>\) radius

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow\left|\frac{-10 m+10}{\sqrt{m^2+1}}\right|>\sqrt{180} \\

& \Rightarrow 100(m-1)^2>180\left(m^2+1\right) \\

& \Rightarrow 2 m^2+5 m+2<0 \\

& \Rightarrow(2 m+1)(m+2)<0 \Rightarrow-2<m<-\frac{1}{2} \Rightarrow m \in(-2,-1 / 2)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 42: The line \(3 x-2 y=k\) meets the circle \(x^2+y^2=4 r^2\) at only one point, if \(k^2=\)

(a) \(20 r^2\)

(b) \(52 r^2\)

(c) \(\frac{52}{9} r^2\)

(d) \(\frac{20}{9} r^2\)

Solution: To solve this, we use the property that if a line meets a circle at only one point, the line must be a tangent to the circle.

Step 1: Identify the Circle and Line Parameters: The circle is \(x^2+y^2=(2 r)^2\).

Center: \((0,0)\)

Radius (\(a\)): \(2 r\)

The line is \(3 x-2 y-k=0\).

Step 2: Apply the Condition of Tangency: For a line to be a tangent, the perpendicular distance from the center \((0,0)\) to the line must be equal to the radius \((2 r)\). The formula for the perpendicular distance \(p\) from \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) to \(A x+B y+C=0\) is:

\(

p=\frac{\left|A x_1+B y_1+C\right|}{\sqrt{A^2+B^2}}

\)

Substituting our values:

\(

\begin{gathered}

2 r=\frac{|3(0)-2(0)-k|}{\sqrt{3^2+(-2)^2}} \\

2 r=\frac{|-k|}{\sqrt{9+4}}

\end{gathered}

\)

\(

2 r=\frac{|k|}{\sqrt{13}}

\)

Step 3: Solve for \(k^2\) Square both sides of the equation to remove the absolute value and the square root:

\(

\begin{gathered}

(2 r)^2=\left(\frac{k}{\sqrt{13}}\right)^2 \\

4 r^2=\frac{k^2}{13} \\

k^2=4 \times 13 \times r^2 \\

k^2=52 r^2

\end{gathered}

\)

Example 43: If \(\frac{x}{\alpha}+\frac{y}{\beta}=1\) touches the circle \(x^2+y^2=a^2\), then point \(\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}, \frac{1}{\beta}\right)\) lies on [JEE (Orissa) 2005]

(a) a straight line

(b) a circle

(c) a parabola

(d) an ellipse

Solution: Step 1: Standardize the line equation The given line is \(\frac{x}{\alpha}+\frac{y}{\beta}=1\). To find the perpendicular distance from the center, let’s rewrite it in the form \(A x+B y+C=0\) :

\(

\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}\right) x+\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right) y-1=0

\)

Step 2: Apply the Condition of Tangency For a line to touch the circle \(x^2+y^2=a^2\) :

Perpendicular distance from center \((0,0)=\) Radius \((a)\)

Using the distance formula \(p=\frac{\left|A x_1+B y_1+C\right|}{\sqrt{A^2+B^2}}\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

a=\frac{\left|\frac{1}{\alpha}(0)+\frac{1}{\beta}(0)-1\right|}{\sqrt{\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}\right)^2+\left(\frac{1}{\beta}\right)^2}} \\

a=\frac{|-1|}{\sqrt{\frac{1}{\alpha^2}+\frac{1}{\beta^2}}}

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 3: Simplify and find the locus Rearrange the equation to isolate the coordinates of the point \(\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}, \frac{1}{\beta}\right)\) :

\(

\sqrt{\frac{1}{\alpha^2}+\frac{1}{\beta^2}}=\frac{1}{a}

\)

Square both sides:

\(

\frac{1}{\alpha^2}+\frac{1}{\beta^2}=\frac{1}{a^2}

\)

Step 4: Identify the geometric shape Let the coordinates of the point be (\(X, Y\)), where \(X=\frac{1}{\alpha}\) and \(Y=\frac{1}{\beta}\). Substituting these into our result:

\(

X^2+Y^2=\left(\frac{1}{a}\right)^2

\)

This equation is in the form \(x^2+y^2=r^2\), which represents a circle with center \((0,0)\) and radius \(\frac{1}{a}\).

The point lies on a circle.

Example 44: If the line \(y \cos \alpha=x \sin \alpha+a \cos \alpha\) be a tangent to the circle \(x^2+y^2=a^2\), then

(a) \(\sin ^2 \alpha=1\)

(b) \(\cos ^2 \alpha=1\)

(c) \(\sin ^2 \alpha=a^2\)

(d) \(\cos ^2 \alpha=a^2\)

Solution: Step 1: Rewrite the line in general form (\(A x+B y+C=0\)) Rearrange \(y \cos \alpha= x \sin \alpha+a \cos \alpha\) to set it to zero:

\(

x \sin \alpha-y \cos \alpha+a \cos \alpha=0

\)

Here:

\(A=\sin \alpha\)

\(B=-\cos \alpha\)

\(C=a \cos \alpha\)

Step 2: Apply the Condition of Tangency For the line to touch the circle \(x^2+y^2=a^2\), the perpendicular distance \((p)\) from the center \((0,0)\) to the line must equal the radius \((a)\).

\(

p=\frac{|A(0)+B(0)+C|}{\sqrt{A^2+B^2}}=a

\)

Substitute the values:

\(

\frac{|a \cos \alpha|}{\sqrt{\sin ^2 \alpha+(-\cos \alpha)^2}}=a

\)

Step 3: Simplify using Trigonometric Identities Recall the fundamental identity: \(\sin ^2 \alpha+\cos ^2 \alpha=1\).

\(

\frac{|a \cos \alpha|}{\sqrt{1}}=a

\)

\(

|a \cos \alpha|=a

\)

Step 4: Solve for the given options Divide both sides by \(a\) (assuming \(a \neq 0\) for the circle to exist):

\(

|\cos \alpha|=1

\)

Now, square both sides to match the format of the options:

\(

\cos ^2 \alpha=1

\)

The correct answer is \(\cos ^2 \alpha=1\).

Example 45: Let \(L_1\) be a straight line passing through the origin and \(L_2\) be the straight line \(x+y=1\). If the intercepts made by the circle \(x^2+y^2-x+3 y=0\) on \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) are equal, then which of the following equations can represent \(L_1\) ? [IIT 1999]

(a) \(x+y=0, x-7 y=0\)

(b) \(x-y=0, x+7 y=0\)

(c) \(7 x+y=0\)

(d) \(x-7 y=0\)

Solution: (b) Step 1: Identify Circle Parameters The given circle is \(x^2+y^2-x+3 y=0\).

Center \((C):\left(\frac{1}{2},-\frac{3}{2}\right)\)

Radius \((r): \sqrt{\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^2+\left(-\frac{3}{2}\right)^2-0}=\sqrt{\frac{1}{4}+\frac{9}{4}}=\sqrt{\frac{10}{4}}\)

Step 2: Calculate the distance from center to \(L_2\) The line \(L_2\) is \(x+y-1=0\). Let \(p_2\) be the perpendicular distance from \(C\left(\frac{1}{2},-\frac{3}{2}\right)\) to \(L_2\) :

\(

p_2=\frac{\left|\frac{1}{2}-\frac{3}{2}-1\right|}{\sqrt{1^2+1^2}}=\frac{|-2|}{\sqrt{2}}=\sqrt{2}

\)

Step 3: Set up the condition for \(L_1\) Since the intercepts (chords) are equal, the distance \(p_1\) from the center to \(L_1\) must also be \(\sqrt{2}\). Let \(L_1\) be \(y=m x\) or \(m x-y=0\) (since it passes through the origin).

\(

\begin{gathered}

p_1=\frac{\left|m\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)-\left(-\frac{3}{2}\right)\right|}{\sqrt{m^2+(-1)^2}}=\sqrt{2} \\

\frac{\left|\frac{m+3}{2}\right|}{\sqrt{m^2+1}}=\sqrt{2}

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 4: Solve for \(m\) Square both sides:

\(

\frac{(m+3)^2}{4\left(m^2+1\right)}=2

\)

\(

\begin{gathered}

(m+3)^2=8\left(m^2+1\right) \\

m^2+6 m+9=8 m^2+8 \\

7 m^2-6 m-1=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Factoring the quadratic:

\(

(7 m+1)(m-1)=0

\)

So, \(m=1\) or \(m=-\frac{1}{7}\).

Step 5: Form the equations

For \(m=1\) : \(y=x \Longrightarrow {x}-{y}={0}\)

For \(m=-\frac{1}{7}: y=-\frac{1}{7} x \Longrightarrow 7 y=-x \Longrightarrow {x}+{7} {y}={0}\)

The equations are \(x-y=0\) and \(x+7 y=0\).

Example 46: If a chord of the circle \(x^2+y^2=32\) makes equal intercepts of length \(l\) on the coordinate axes, then

(a) \(l \in(-8,8)\)

(b) \(l \in(-4 \sqrt{2}, 4 \sqrt{2})\)

(c) \(l \in(0,8)\)

(d) \(l \in(-8,0)\)

Solution: Step 1: Identify Circle Parameters The circle equation is \(x^2+y^2=32\).

Center \((O):(0,0)\)

Radius (\(r\)) : \(\sqrt{32}=4 \sqrt{2}\)

Step 2: Determine the Equation of the Chord The problem states the chord makes equal intercepts of length \(l\) on the coordinate axes. Using the intercept form of a straight line, the equation of the chord is:

\(

\frac{x}{l}+\frac{y}{l}=1 \Longrightarrow x+y=l \Longrightarrow x+y-l=0

\)

Step 3: Apply the Geometric Condition for Intersection For a line to be a chord (and not just a line outside the circle), its perpendicular distance \((p)\) from the center must be strictly less than the radius (\(r\)).

\(

{p}<{r}

\)

Calculating the perpendicular distance from \((0,0)\) to \(x+y-l=0\) :

\(

p=\frac{|0+0-l|}{\sqrt{1^2+1^2}}=\frac{|l|}{\sqrt{2}}

\)

Step 4: Solve the Inequality Set the distance less than the radius:

\(

\begin{gathered}

\frac{|l|}{\sqrt{2}}<4 \sqrt{2} \\

|l|<4 \sqrt{2} \times \sqrt{2} \\

|l|<8

\end{gathered}

\)

This inequality results in the range:

\(

-8<l<8

\)

\(

l \in(-8,8)

\)

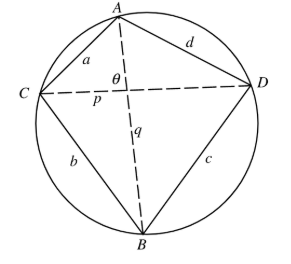

Segments of Secants, Chords and Tangent

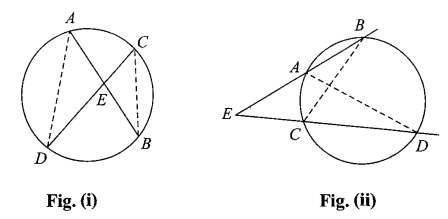

Secants \(A B\) and \(C D\) intersect insider the circle in Figure (i) and outside the circle in Figure (ii).

From the figure, we have \(\angle D C B=\angle D A B\) and

\(

\angle A D C=\angle A B C

\)

Hence \(\triangle A D E \sim \triangle C B E\).

\(

\therefore \frac{A E}{C E}=\frac{D E}{B E} \therefore A E \times B E=C E \times D E

\)

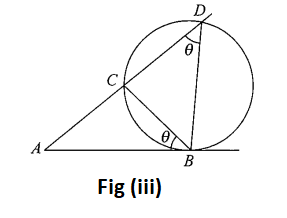

In Figure (iii), \(A D\) is secant and \(A B\) is tangent.

From Figure (iii), \(\triangle A B D \sim \triangle A C B\)

\(

\therefore \frac{A B}{A C}=\frac{A D}{A B} \therefore A B^2=A C \times A D

\)

Tangent of a Circle