10.8 JEE Entrance Corner

DIRECTION COSINES AND DIRECTION RATIOS

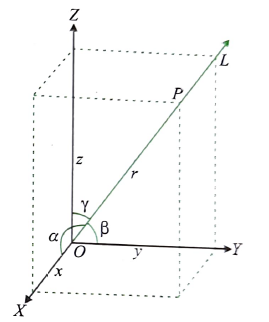

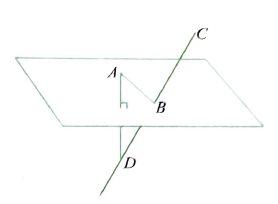

If a directed line \(L\), passing through the origin, makes angles \(\alpha, \beta\) and \(\gamma\) with the \(x\)-, \(y\) – and \(z\)-axes, respectively, called direction angles, then the cosines of these angles, namely, \(\cos \alpha, \cos \beta\) and \(\cos \gamma\), are called the direction cosines of the directed line \(L\).

If we reverse the direction of \(L\), the direction angles are replaced by their supplements, i.e., \(\pi-\alpha, \pi-\beta\) and \(\pi-\gamma\). Thus, the signs of the direction cosines are reversed.

Note that a given line in space can be extended in two opposite directions, and so it has two sets of direction cosines. In order to have a unique set of direction cosines for a given line in space, we must take the given line as a directed line. These unique direction cosines are denoted by \(l, m\) and \(n\).

If the given line in space does not pass through the origin, then in order to find its direction cosines, we draw a line through the origin and parallel to the given line. Now take one of the directed lines from the origin and find its direction cosines as two parallel lines have the same set of direction cosines.

Anythree numbers which are proportional to the direction cosines of a line are called the direction ratios of the line. If \(l, m\) and \(n\) are direction cosines and \(a, b\) and \(c\) are the direction ratios of a line, then \(a=\lambda l\), \(b=\lambda m\) and \(c=\lambda n\) for any non-zero \(\lambda \in R\).

Notes:

- Direction cosines of the \(x\)-axis are \((1,0,0)\).

Direction cosines of the \(y\)-axis are \((0,1,0)\).

Direction cosines of the \(z\)-axis are \((0,0,1)\). - Let \(O P\) be any line passing through the origin \(O\) which has direction cosines \(\cos \alpha \cos \beta\) and \(\cos \gamma\), i.e., \((l, m, n)\) where distance \(O P=r\), i.e., coordinates of \(P\) are ( \(r \cos \alpha, r \cos \beta, r \cos \gamma\) ).

- If \(l, m\) and \(n\) are the direction cosines of a vector, then \(l^2+m^2+n^2=1\).

- \(\vec{r}=|\vec{r}|(l \hat{i}+m \hat{j}+n \hat{k})\) and \(\hat{r}=l \hat{i}+m \hat{j}+n \hat{k}\).

Direction Ratios

Let \(l, m\) and \(n\) be the direction cosines of a vector \(\vec{r}\) and \(a, b\) and \(c\) be three numbers such that \(a, b, c\) are proportional to \(l, m\) and \(n\). Therefore,

\(

\frac{l}{a}=\frac{m}{b}=\frac{n}{c}=k \text { or }(l, m, n)=(k a, k b, k c)

\)

Hence, \(a, b\) and \(c\) are direction ratios.

For example. if \((1 / \sqrt{3},-1 / \sqrt{3}, 1 / \sqrt{3})\) are direction cosines of a vector \(\vec{r}\), then its direction ratios are \((1,-1,1)\) or \((-1,1,-1)\) or \((2,-2,2)\) or \((\lambda,-\lambda, \lambda) \ldots\)

It is evident from the above definition that to obtain the direction ratios of a vector from its direction cosines, we just multiply them by a common number.

“That shows there can be an infinite number of direction ratios for a given vector, but the direction cosines are unique.”

Direction ratios of a line joining two points

For points \(P\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right)\) and \(Q\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\),

\(

\text { Vector } \overrightarrow{P Q}=\left(x_2-x_1\right) \hat{i}+\left(y_2-y_1\right) \hat{j}+\left(z_2-z_1\right) \hat{k}

\)

Then the direction ratios of \(P Q\) are \(\left\langle\left(x_2-x_1\right),\left(y_2-y_1\right),\left(z_2-z_1\right)\right\rangle\).

To obtain direction cosines from direction ratios

Let \(a, b\) and \(c\) be the direction ratios of a vector \(\vec{r}\) having direction cosines \(l, m\) and \(n\). Then

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& l=\lambda a, m=\lambda b, n=\lambda c \text { (by definition) }\\

\therefore & l^2+m^2+n^2=1 \\

\Rightarrow & a^2 \lambda^2+b^2 \lambda^2+c^2 \lambda^2=1 \\

\Rightarrow & \lambda= \pm \frac{1}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}} \\

\Rightarrow & l= \pm \frac{a}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}, m= \pm \frac{b}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}, n= \pm \frac{c}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}

\end{array}

\)

For Example, Let the direction ratios of a line be 3,1 and -2.

Direction cosines are

\(

\left(\frac{3}{\sqrt{3^2+1^2+(-2)^2}}, \frac{1}{\sqrt{3^2+1^2+(-2)^2}}, \frac{-2}{\sqrt{3^2+1^2+(-2)^2}}\right) \Rightarrow\left(\frac{3}{\sqrt{14}}, \frac{1}{\sqrt{14}}, \frac{-2}{\sqrt{14}}\right)

\)

Remarks

- If \(\vec{r}=a \hat{i}+b \hat{j}+c \hat{k}\) is a vector having direction cosines \(l, m\) and \(n\), then \(l=\frac{a}{|\vec{r}|}, m=\frac{b}{|\vec{r}|}, n=\frac{c}{|\vec{r}|}\).

- Direction cosines of parallel vectors:

Let \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) be two parallel vectors. Then \(\vec{b}=\lambda \vec{a}\) for some \(\lambda\).

If \(\vec{a}=a_1 \hat{i}+a_2 \hat{j}+a_3 \hat{k}\), then \(\vec{b}=\lambda \vec{a} \Rightarrow \vec{b}=\left(\lambda a_1\right) \hat{i}+\left(\lambda a_2\right) \hat{j}+\left(\lambda a_3\right) \hat{k}\)

This shows that \(\vec{b}\) has direction ratios \(\lambda a_1, \lambda a_2\) and \(\lambda a_3\), i.e., \(a_1, a_2\) and \(a_3\) because \(\lambda a_1: \lambda a_2: \lambda a_3 =a_1: a_2: a_3\). Thus, \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) have equal direction ratios and hence equal direction cosines too. - If the direction ratios of \(\vec{r}\) are \(a, b\) and \(c\), then \(\vec{r}=\frac{|\vec{r}|}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}(a \hat{i}+b \hat{j}+c \hat{k})\).

- Projections of \(\vec{r}\) on the coordinate axes are: \(l|\vec{r}|, m|\vec{r}|\) and \(n|\vec{r}|\).

- The projection of a segment joining points \(P\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right)\) and \(Q\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\) on a line with direction cosines \(l, m\) and \(n\) is \(\left(x_2-x_1\right) l+\left(y_2-y_1\right) m+\left(z_2-z_1\right) n\).

- If \(l_1, m_1, n_1\) and \(l_2, m_2, n_2\) are the direction cosines of two concurrent lines, then the direction cosines of the lines bisecting the angles between them are proportional to \(l_1 \pm l_2, m_1 \pm m_2\) and \(n_1 \pm n_2\).

- Acute angle \(\theta\) between the two lines having direction cosines \(l_1, m_1, n_1\) and \(l_2, m_2, n_2\) is given by

\(

\cos \theta=\left|l_1 l_2+m_1 m_2+n_1 n_2\right|, \sin \theta=\sqrt{\left(l_1 m_2-l_2 m_1\right)^2+\left(m_1 n_2-m_2 n_1\right)^2+\left(n_1 l_2-n_2 l_1\right)^2}

\) - If \(a_1, b_1, c_1\) and \(a_2, b_2, c_2\) are the direction ratios of two lines, then the acute angle \(\theta\) between them is given by \(\cos \theta=\frac{\left|a_1 a_2+b_1 b_2+c_1 c_2\right|}{\sqrt{a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2} \sqrt{a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2}}\),

\(

\sin \theta=\frac{\sqrt{\left(a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1\right)^2+\left(b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1\right)^2+\left(c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1\right)^2}}{\sqrt{a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2} \sqrt{a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2}}

\) - Two lines having direction \(\operatorname{cosines} l_1, m_1, n_1\) and \(l_2, m_2, n_2\) are

a. perpendicular if and only if \(l_1 l_2+m_1 m_2+n_1 n_2=0\).

b. parallel if and only if \(\frac{l_1}{l_2}=\frac{m_1}{m_2}=\frac{n_1}{n_2}\) - Two lines having direction ratios \(a_1, b_1, c_1\) and \(a_2, b_2, c_2\) are

a. perpendicular if and only if \(a_1 a_2+b_1 b_2+c_1 c_2=0\)

b. parallel if and only if \(\frac{a_1}{a_2}=\frac{b_1}{b_2}=\frac{c_1}{c_2}\)

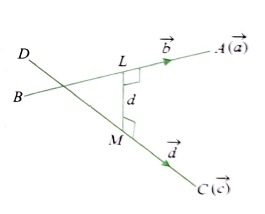

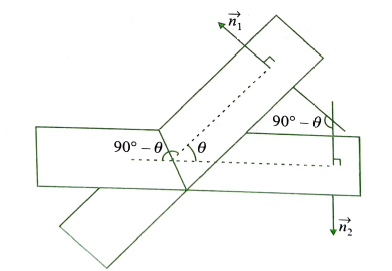

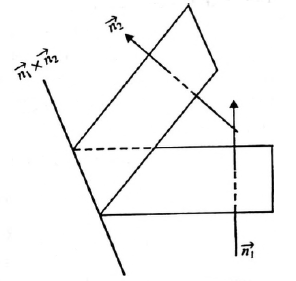

Direction ratio of line along the bisector of two given lines

If \(l_1, m_1\) and \(n_1\) and \(l_2, m_2\) and \(n_2\) are the direction cosines of the two lines inclined to each other at an angle \(\theta\), then the direction cosines of the

a. internal bisector of the angle between these lines are \(\frac{l_1+l_2}{2 \cos (\theta / 2)}, \frac{m_1+m_2}{2 \cos (\theta / 2)}\) and \(\frac{n_1+n_2}{2 \cos (\theta / 2)}\), and

b. external bisector of the angle between these lines are \(\frac{l_1-l_2}{2 \sin (\theta / 2)}, \frac{m_1-m_2}{2 \sin (\theta / 2)}\) and \(\frac{n_1-n_2}{2 \sin (\theta / 2)}\).

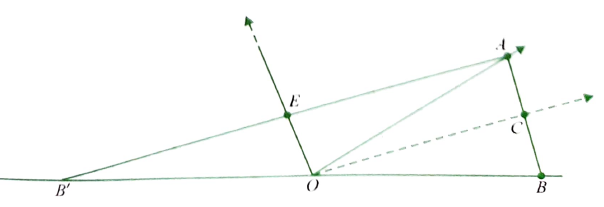

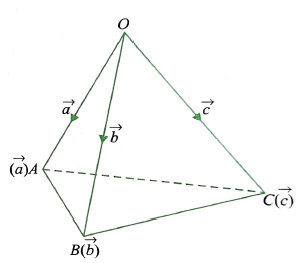

Proof:

Let \(O A\) and \(O B\) be two lines with direction cosines \(l_1, m_1, n_1\) and \(l_2, m_2, n_2\). Let \(O A=O B=1\). Then the coordinates of \(A\) and \(B\) are ( \(l_1, m_1, n_1\) ) and ( \(l_2, m_2, n_2\) ), respectively. Let \(O C\) be the bisector of \(\angle A O B\). Then \(C\) is the midpoint of \(A B\) and so its coordinates are

\(

\left(\frac{l_1+l_2}{2}, \frac{m_1+m_2}{2}, \frac{n_1+n_2}{2}\right)

\)

Therefore, the direction ratios of \(O C\) are \(\frac{l_1+l_2}{2}, \frac{m_1+m_2}{2}\) and \(\frac{n_1+n_2}{2}\). We have

\(

\begin{aligned}

O C & =\sqrt{\left(\frac{l_1+l_2}{2}\right)^2+\left(\frac{m_1+m_2}{2}\right)^2+\left(\frac{n_1+n_2}{2}\right)^2} \\

& =\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\left(l_1^2+m_1^2+n_1^2\right)+\left(l_2^2+m_2^2+n_2^2\right)+2\left(l_1 l_2+m_1 m_2+n_1 n_2\right)}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(=\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{2+2 \cos \theta} \quad\left(\because \cos \theta=l_1 l_2+m_1 m_2+n_1 n_2\right)\)

\(

=\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{2(1+\cos \theta)}=\cos \left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right)

\)

Therefore, the direction cosines of \(\overrightarrow{O C}\) are \(\frac{l_1+l_2}{2(O C)}, \frac{m_1+m_2}{2(O C)}, \frac{n_1+n_2}{2(O C)}\)

\(

\frac{l_1+l_2}{2 \cos (\theta / 2)}, \frac{m_1+m_2}{2 \cos (\theta / 2)}, \frac{n_1+n_2}{2 \cos (\theta / 2)}

\)

In the figure, \(O E\) is the external bisector.

The coordinates of \(E\) are \(\frac{l_1-l_2}{2}, \frac{m_1-m_2}{2}\) and \(\frac{n_1-n_2}{2}\).

Therefore, direction ratios of \(O E\) are \(\frac{l_1-l_2}{2}, \frac{m_1-m_2}{2}\) and \(\frac{n_1-n_2}{2}\).

Also,

\(

\begin{aligned}

O E & =\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{2-2 \cos \theta} \\

& =\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{2(1-\cos \theta)} \\

& =\sin (\theta / 2)

\end{aligned}

\)

Therefore, the direction cosines of \(\overrightarrow{O E}\) are \(\frac{l_1-l_2}{2 \sin (\theta / 2)}, \frac{m_1-m_2}{2 \sin (\theta / 2)}\) and \(\frac{n_1-n_2}{2 \sin (\theta / 2)}\).

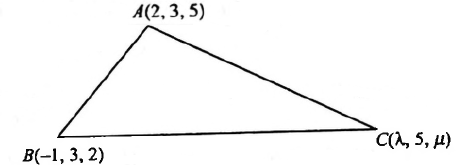

Illustration 1: \(A B C\) is a triangle and \(A=(2,3,5), B=(-1,3,2)\) and \(C=(\lambda, 5, \mu)\). If the median through \(A\) is equally inclined to the axes, then find the value of \(\lambda\) and \(\mu\).

Solution:

Midpoint of \(B C\) is \(\left(\frac{\lambda-1}{2}, 4, \frac{2+\mu}{2}\right)\)

Direction ratios of the median through \(A\) are

\(

\frac{\lambda-1}{2}-2,4-3 \text { and } \frac{2+\mu}{2}-5, \text { i.e. } \frac{\lambda-5}{2}, 1 \text { and } \frac{\mu-8}{2} .

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { The median is equally inclined to the axes; so the direction ratios must be equal. Therefore, }\\

&\frac{\lambda-5}{2}=1=\frac{\mu-8}{2} \Rightarrow \lambda=7, \mu=10

\end{aligned}

\)

Illustration 2: If \(\alpha, \beta\) and \(\gamma\) are the angles which a directed line makes with the positive directions of the co-ordinates axes, then find the value of \(\sin ^2 \alpha+\sin ^2 \beta+\sin ^2 \gamma\).

Solution: The direction cosines of the line are \(l=\cos \alpha, m=\cos \beta\) and \(n=\cos \gamma\).

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\because & l^2+m^2+n^2=1, \cos ^2 \alpha+\cos ^2 \beta+\cos ^2 \gamma=1 \\

\therefore & 1-\sin ^2 \alpha+1-\sin ^2 \beta+1-\sin ^2 \gamma=1 \\

\text { or } & \sin ^2 \alpha+\sin ^2 \beta+\sin ^2 \gamma=2

\end{array}

\)

Illustration 3: A line \(O P\) through origin \(O\) is inclined at \(30^{\circ}\) and \(45^{\circ}\) to \(O X\) and \(O Y\), respectively. Then find the angle at which it is inclined to \(O Z\).

Solution: Let \(l, m\) and \(n\) be the direction cosines of the given vector. Then \(l^2+m^2+n^2=1\).

If \(l=\cos 30^{\circ}=\sqrt{3} / 2, m=\cos 45^{\circ}=1 / \sqrt{2}\), then \(\frac{3}{4}+\frac{1}{2}+n^2=1\).

\(n^2=-1 / 4\), which is not possible. So, such a line cannot exist.

Illustration 4: A line passes through the points \((6,-7,-1)\) and \((2,-3,1)\). Find the direction cosines of the line if the line makes an acute angle with the positive direction of the \(x\)-axis.

Solution: Let \(l, m\) and \(n\) be the direction cosines of the given line. As it makes an acute angle with the \(x\)-axis, \(l>0\). The line passes through \((6,-7,-1)\) and \((2,-3,1)\); therefore, its direction ratios are \((6-2,-7+3,-1 -1)\) or \((4,-4,-2)\). Hence, the direction cosines of the given line are \(2 / 3,-2 / 3\) and \(-1 / 3\).

Illustration 5: Find the ratio in which the \(y-z\) plane divides the join of the points \((-2,4,7)\) and \((3,-5,8)\) Sol. Let the \(y-z\) plane divide the join of \(P(-2,4,7)\) and \(Q(3,-5,8)\) in the ratio \(\lambda: 1\).

Solution: Let the \(y-z\) plane divide the join of \(P(-2,4,7)\) and \(Q(3,-5,8)\) in the ratio \(\lambda: 1\).

If \(\left(\frac{3 \lambda-2}{\lambda+1}, \frac{-5 \lambda+4}{\lambda+1}, \frac{8 \lambda+7}{\lambda+1}\right)\) is in the \(y-z\) plane, then its \(x\)-coordinate is zero. Therefore,

\(

\frac{3 \lambda-2}{\lambda+1}=0 \text { or } 3 \lambda-2=0

\)

\(

\lambda=2 / 3

\)

Illustration 6: If \(A(3,2,-4), B(5,4,-6)\) and \(C(9,8,-10)\) are three collinear points, then find the ratio in which point \(C\) divides \(A B\).

Solution: Let \(C\) divide \(A B\) in the ratio \(\lambda: 1\). Then

\(

C \equiv\left(\frac{5 \lambda+3}{\lambda+1}, \frac{4 \lambda+2}{\lambda+1}, \frac{-6 \lambda-4}{\lambda+1}\right)=(9,8-10)

\)

Comparing, we get

\(

5 \lambda+3=9 \lambda+9 \text { or } 4 \lambda=-6 \text { or } \lambda=-3 / 2

\)

Also, from \(4 \lambda+2=8 \lambda+8\) and \(-6 \lambda-4=-10 \lambda-10\), we get the same value of \(\lambda\)

Illustration 7: If the sum of the squares of the distance of a point from the three coordinate axes is 36 , then find its distance from the origin.

Solution: Let \(P(x, y, z)\) be the point. Now under the given condition,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& {\left[\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\right]^2+\left[\sqrt{y^2+z^2}\right]^2+\left[\sqrt{z^2+x^2}\right]^2=36} \\

& x^2+y^2+z^2=18

\end{aligned}

\)

Then distance from the origin to point ( \(x, y, z\) ) is

\(

\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}=\sqrt{18}=3 \sqrt{2}

\)

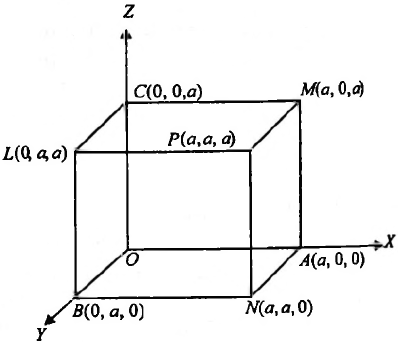

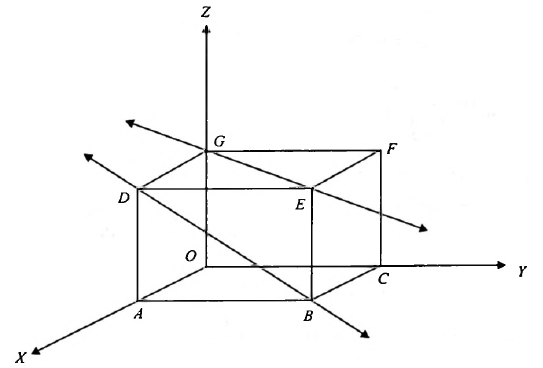

Illustration 8: A line makes angles \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma\) and \(\delta\) with the diagonals of a cube. Show that \(\cos ^2 \alpha+\cos ^2 \beta+\cos ^2 \gamma+\cos ^2 \delta=4 / 3\).

Solution: The four diagonals of a cube are \(A L, B M, C N\) and \(O P\).

Direction cosines of \(O P\) are \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}, \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\) and \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\).

Direction cosines of \(A L\) are \(\frac{-1}{\sqrt{3}}, \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\) and \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\).

Direction cosines of \(B M\) are \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}, \frac{-1}{\sqrt{3}}\) and \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\).

Direction cosines of \(C N\) are \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}, \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\) and \(\frac{-1}{\sqrt{3}}\).

Let \(l, m\) and \(n\) be the direction cosines of a line which is inclined at angles \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma\) and \(\delta\), respectively, to the four diagonals; then

\(

\begin{aligned}

\cos \alpha & =l \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}+m \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}+n \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \\

& =\frac{l+m+n}{\sqrt{3}}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\text { Similarly, } \quad \cos \beta=\frac{-l+m+n}{\sqrt{3}}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \cos \gamma=\frac{l-m+n}{\sqrt{3}} \\

& \begin{aligned}

\cos \delta=\frac{l+m-n}{\sqrt{3}} & \\

\cos ^2 \alpha+\cos ^2 \beta+\cos ^2 \gamma+\cos ^2 \delta & =\frac{1}{3}\left[(l+m+n)^2+(-l+m+n)^2+(l-m+n)^2+(l+m-n)^2\right] \\

& =\frac{1}{3} \cdot 4\left(l^2+m^2+n^2\right)=\frac{4}{3}

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Illustration 9: Find the angle between the lines whose direction cosines are given by \(l+m+n=0\) and \(2 l^2+2 m^2-n^2=0\).

Solution: \(l^2+m^2+n^2=1 \dots(i)\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& l+m+n=0 \dots(ii) \\

& 2 l^2+2 m^2-n^2=0 \dots(iii) \\

& 2\left(1-n^2\right)=n^2 \text { or } 3 n^2=2 \text { or } n= \pm \sqrt{2 / 3} \dots(iv) \\

& 2\left(l^2+m^2\right)=n^2=(-(l+m))^2 \text { or } l=m \dots(v) \\

& l+m= \pm \sqrt{2 / 3} \text { or } 2 l= \pm \sqrt{2 / 3} \\

& l= \pm 1 / \sqrt{6}, m= \pm 1 / \sqrt{6}

\end{aligned}

\)

Direction cosines are

\(

\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}, \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}, \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}}\right) \text { and }\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}, \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}},-\sqrt{\frac{2}{3}}\right)

\)

\(

\left(-\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}},-\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}, \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}}\right) \text { and }\left(-\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}},-\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}},-\sqrt{\frac{2}{3}}\right)

\)

The angle between these lines in both the cases is \(\cos ^{-1}\left(-\frac{1}{3}\right)\).

Illustration 10: A mirror and a source of light are situated at the origin \(O\) and at a point on \(O X\), respectively. A ray of light from the source strikes the mirror and is reflected. If the direction ratios of the normal to the plane are \(1,-1,1\), then find the DCs of the reflected ray.

Solution: Let the source of light be situated at \(A(a, 0,0)\), where \(a \neq 0\).

Let \(O A\) be the incident ray and \(O B\) the reflected ray.

\(O N\) is the normal to the mirror at \(O\). Therefore,

\(

\angle A O N=\angle N O B=\theta / 2 \quad \text { (say) }

\)

Direction ratios of \(O A\) are \(a, 0\) and 0 and so its direction cosines are 1,0 and 0.

Direction ratios of \(O N\) are \(1 / \sqrt{3},-1 / \sqrt{3}\) and \(1 / \sqrt{3}\). Therefore,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \angle A O N=\angle N O B=(\theta / 2) \quad(\text { say }) \\

& \cos (\theta / 2)=1 / \sqrt{3}

\end{aligned}

\)

Let \(l, m\) and \(n\) be the direction cosines of the reflected ray \(O B\). Then

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& \frac{l+1}{2 \cos (\theta / 2)}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}, \frac{m+0}{2 \cos (\theta / 2)}=-\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \text { and } \frac{n+0}{2 \cos (\theta / 2)}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \\

\Rightarrow & l=\frac{2}{3}-1, m=\frac{-2}{3}, n=\frac{2}{3} \\

\text { or } & l=-\frac{1}{3}, m=-\frac{2}{3}, n=\frac{2}{3}

\end{array}

\)

LINE IN SPACE

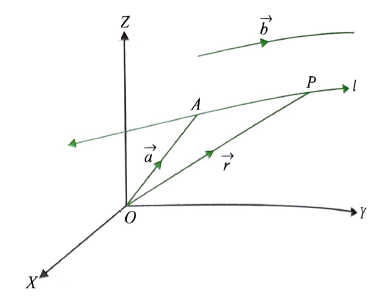

Equation of Straight Line Passing through a Given Point and Parallel to a Given Vector

Vector Form

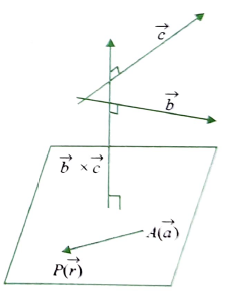

Line Passing through Point \(\mathrm{A}(\vec{a})\) and Parallel to Vector \(\vec{b}\)

Let \(A\) be the given point and let \(A P\) be the given line through \(A\). Let \(\vec{b}\) be any vector parallel to the given line.

Position vector of point \(A\) is \(\vec{a}\).

Let \(P\) be any point on line \(A P\), and let its position vector be \(\vec{r}\).

Then, we have \(\vec{r}=\overrightarrow{O P}=\overrightarrow{O A}+\overrightarrow{A P}=\vec{a}+\lambda \vec{b} \quad\) (where \(\overrightarrow{A P}=\lambda \vec{b}\) ) and \(\lambda\) is some scalar.

Hence, the vector equation of straight line, \(\vec{r}=\vec{a}+\lambda \vec{b} \dots(1)\).

Here, \(\vec{r}\) is the position vector of any point \(P(x, y, z)\) on the line. So \(\vec{r}=x \hat{i}+y \hat{j}+z \hat{k}\).

In particular, the equation of straight line through origin and parallel to \(\vec{b}\) is \(\vec{r}=\lambda \vec{b}\).

Cartesian Form

Let the coordinates of the given point \(A\) be \(\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right)\) and the direction ratios of the line be \(a, b\) and \(c\). Consider the coordinates of any point \(P\) be \((x, y, z)\). Then

\(

\vec{r}=x \hat{i}+y \hat{j}+z \hat{k}, \vec{a}=x_1 \hat{i}+y_1 \hat{j}+z_1 \hat{k} \text { and } \vec{b}=a \hat{i}+b \hat{j}+c \hat{k}

\)

Substituting these values in (i) and equating the coefficients of \(\hat{i}, \hat{j}\) and \(\hat{k}\), we get

\(

x=x_1+\lambda a ; y=y_1+\lambda b ; z=z_1+\lambda c

\)

These are parametric equations of the line.

Eliminating the parameter \(\lambda\), we get \(\frac{x-x_1}{a}=\frac{y-y_1}{b}=\frac{z-z_1}{c}\).

Remarks

- Here any point on the line is \((x, y, z) \equiv\left(x_1+\lambda a, y_1+\lambda b, z_1+\lambda c\right)\) ( \(\lambda\) being a parameter).

Example 1: Find the equation of the line in vector form passing through the point \((4,-2,5)\) and parallel to the vector \(3 \hat{i}-\hat{j}+2 \hat{k}\). Hence, find the equation in Cartesian form.

Solution: Given that the line pass through the point \(A(4,-2,5)\) and parallel to the vector \(\vec{b}=3 \hat{\imath}-\hat{\jmath}+2 \hat{k}\).

Let \(\vec{a}\) be the position vector of the point A

\(

\therefore \vec{a}=4 \hat{\imath}-2 \hat{\jmath}+5 \hat{k}

\)

\(\therefore\) The vector equation of line passing through the point. \(\mathrm{A}(\vec{a})\) and parallel to vector \(\vec{b}\) is \(\vec{r}=\vec{a}+\lambda \vec{b}\) where \(\lambda\) is scalar

\(

\vec{r}=(4 \hat{\imath}-2 \hat{\jmath}+5 \hat{k})+\lambda(3 \hat{\imath}-\hat{\jmath}+2 \hat{k} .)

\)

If \(\vec{r}=x \hat{\imath}+y \hat{\jmath}+z \hat{k}\) then

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x \hat{\imath}+y \hat{\jmath}+z \hat{k}=(4 \hat{\imath}-2 \hat{\jmath}+5 \hat{k})+\lambda(3 \hat{\imath}-\hat{\jmath}+2 \hat{k}) \\

& \quad(x-4) \hat{\imath}+(y+2) \hat{\jmath}+(z-5) \hat{k}=3 \lambda \hat{\imath}-\lambda \hat{\jmath}+2 \lambda \hat{k}

\end{aligned}

\)

Comparing the coefficients of \(\hat{\imath}, \hat{\jmath}, \hat{k}\) on both sides.

\(

x-4=3 \lambda, y+2=-\lambda, z-5=2 \lambda

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\frac{x-4}{3}=\frac{y+2}{-1}=\frac{z-5}{2}=\lambda\\

&\therefore \text { Cartesian form of the equation of line is } \frac{x-4}{3}=\frac{y+2}{-1}=\frac{z-5}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

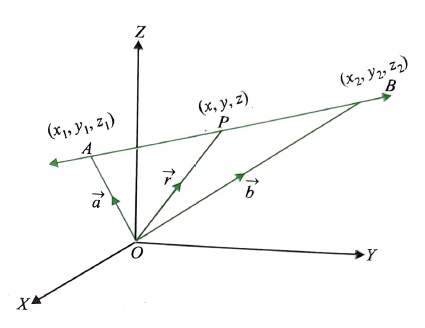

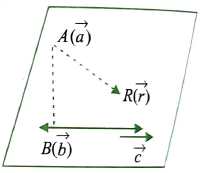

EQUATION OF LINE PASSING THROUGH TWO GIVEN POINTS

Vector Form

From the figure, \(\overrightarrow{O P}=\vec{r}, \overrightarrow{O A}=\vec{a}\) and \(\overrightarrow{O B}=\vec{b}\). Since \(\overrightarrow{A P}\) is collinear with \(\overrightarrow{A B}, \overrightarrow{A P}=\lambda \overrightarrow{A B}\) for some scalar \(\lambda\), we have

\(

\overrightarrow{O P}-\overrightarrow{O A}=\lambda(\overrightarrow{O B}-\overrightarrow{O A})

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \vec{r}-\vec{a}=\lambda(\vec{b}-\vec{a}) \\

& \vec{r}=\vec{a}+\lambda(\vec{b}-\vec{a}) \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

Therefore, the equation of a straight line passing through \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) is \(\vec{r}=\vec{a}+\lambda(\vec{b}-\vec{a})\).

Cartesian Form

We have \(\vec{r}=x \hat{i}+y \hat{j}+z \hat{k}, \vec{a}=x_1 \hat{i}+y_1 \hat{j}+z_1 \hat{k}\) and \(\vec{b}=x_2 \hat{i}+y_2 \hat{j}+z_2 \hat{k}\).

Substituting these values in (i), we get

\(

x \hat{i}+y \hat{j}+z \hat{k}=x_1 \hat{i}+y_1 \hat{j}+z_1 \hat{k}+\lambda\left[\left(x_2-x_1\right) \hat{i}+\left(y_2-y_1\right) \hat{j}+\left(z_2-z_1\right) \hat{k}\right]

\)

Equating the coefficients of \(\hat{i}, \hat{j}\) and \(\hat{k}\), we get

\(

x=x_1+\lambda\left(x_2-x_1\right) ; y=y_1+\lambda\left(y_2-y_1\right) ; z=z_1+\lambda\left(z_2-z_1\right)

\)

On eliminating \(\lambda\), we obtain \(\frac{x-x_1}{x_2-x_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{y_2-y_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{z_2-z_1}=\lambda\) which is the equation of the line in Cartesian form.

Example 2: The Cartesian equation of a line is \(\frac{x-3}{2}=\frac{y+1}{-2}=\frac{z-3}{5}\). Find the vector equation of the line.

Solution: The given line is \(\frac{x-3}{2}=\frac{y+1}{-2}=\frac{z-3}{5}\).

Note that it passes through \((3,-1,3)\) and is parallel to the line whose direction ratios are \(2,-2\) and 5. Therefore, its vector equation is \(\vec{r}=3 \hat{i}-\hat{j}+3 \hat{k}+\lambda(2 \hat{i}-2 \hat{j}+5 \hat{k})\), where \(\lambda\) is a parameter.

Example 3: The Cartesian equations of a line are \(6 x-2=3 y+1=2 z-2\). Find its direction ratios and also find a vector equation of the line.

Solution: The given line is \(6 x-2=3 y+1=2 z-2 \dots(i)\)

To put it in the symmetrical form, we must make the coefficients of \(x, y\) and \(z\) as 1. To do this, we divide each of the expressions in (i) by 6 and obtain \(\frac{x-(1 / 3)}{1}=\frac{y+(1 / 3)}{2}=\frac{z-1}{3}\).

This shows that the given line passes through \((1 / 3,-1 / 3,1)\) and is parallel to the line whose direction ratios are 1,2 and 3. Therefore, its vector equation is

\(

\vec{r}=\frac{1}{3} \hat{i}-\frac{1}{3} \hat{j}+\hat{k}+\lambda(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k})

\)

Example 4: A line passes through the point with position vector \(2 \hat{i}-3 \hat{j}+4 \hat{k}\) and is in the direction of \(3 \hat{i}+4 \hat{j}-5 \hat{k}\). Find the equations of the line in vector and Cartesian forms.

Solution: Since the line passes through \(2 \hat{i}-3 \hat{j}+4 \hat{k}\) and has direction of \(3 \hat{i}+4 \hat{j}-5 \hat{k}\), its vector equation is

\(

\vec{r}=\hat{a}+\lambda \hat{b} \Rightarrow \vec{r}=2 \hat{i}-3 \hat{j}+4 \hat{k}+\lambda(3 \hat{i}+4 \hat{j}-5 \hat{k}), \text { where } \lambda \text { is a scalar parameter. } \dots(i)

\)

Cartesian equivalent of (i) is \(\frac{x-2}{3}=\frac{y+3}{4}=\frac{z-4}{-5}\)

Example 5: Find the vector equation of line passing through \(A(3,4,-7)\) and \(B(1,-1,6)\). Also find its cartesian equations.

Solution: Since the line passes through \(A(3 \hat{i}+4 \hat{j}-7 \hat{k})\) and \(B(\hat{i}-\hat{j}+6 \hat{k})\), its vector equation is

\(

\begin{aligned}

\vec{r} & =3 \hat{i}+4 \hat{j}-7 \hat{k}+\lambda[(\hat{i}-\hat{j}+6 \hat{k})-(3 \hat{i}+4 \hat{j}-7 \hat{k})] \\

& =3 \hat{i}+4 \hat{j}-7 \hat{k}-\lambda(2 \hat{i}+5 \hat{j}-13 \hat{k}) \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

where \(\lambda\) is a parameter.

The Cartesian equivalent of (i) is \(\frac{x-3}{2}=\frac{y-4}{5}=\frac{z+7}{-13}\).

Example 6: Find the equation of a line which passes through the point \((2,3,4)\) and which has equal intercepts on the axes.

Solution: Since line has equal intercepts on axes, it is equally inclined to axes.

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & \text { Line is along the vector } \vec{a}(\hat{i}+\hat{j}+\hat{k}) \\

\Rightarrow & \text { Equation of line }=\frac{x-2}{1}=\frac{y-3}{1}=\frac{z-4}{1}

\end{array}

\)

Example 7: Find the points where line \(\frac{x-1}{2}=\frac{y+2}{-1}=\frac{z}{1}\) intersects \(x y, y z\) and \(z x\) planes.

Solution: Line meets \(x y\)-plane where \(z=0\)

Hence, from the given equation of line, \(\frac{x-1}{2}=\frac{y+2}{-1}=\frac{0}{1}\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x=1 \text { and } y=-2 \text {. }

\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad\) Line meets \(x y\)-plane at \((1,-2,0)\).

Line meets \(y z\)-plane where \(x=0\)

Hence, from the given equation of line, \(\frac{0-1}{2}=\frac{y+2}{-1}=\frac{z}{1}\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & z=\frac{-1}{2} \text { and } y=-\frac{3}{2} \\

\Rightarrow & \text { Line meets } y z \text {-plane at }\left(0,-\frac{3}{2}, \frac{-1}{2}\right)

\end{array}

\)

Line meets \(z x\)-plane where \(y=0\)

Hence, from the given equation of line \(\frac{x-1}{2}=\frac{0+2}{-1}=\frac{z}{1}\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & z=-2, x=-3 \\

\Rightarrow & \text { Line meets } z x \text {-plane at }(-3,0,-2)

\end{array}

\)

Example 8: Find the equation of line \(x+y-z-3=0=2 x+3 y+z+4\) in symmetric form. Find the direction ratios of the line.

Solution: In the section of planes we will see that equation of the form \(a x+b y+c z+d=0\) is the equation of the plane in the space.

Now equation of line in the form \(x+y-z-3=0=2 x+3 y+z+4\) means set of those points in space which are common to the planes \(x+y-z-3=0\) and \(2 x+3 y+z+4=0\), which lie on the line of intersection of planes.

For example, equation of \(x\)-axis is \(y=z=0\) where \(x y\)-plane ( \(z=0\) ) and \(x z\)-plane ( \(y=0\) ) intersect.

Now to get the equation of line in symmetric form, in above equations, first we eliminate any one of the variables, say \(z\). Then adding \(x+y-z-3=0\) and \(2 x+3 y+z+4=0\), we get

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 3 x+4 y+1=0 \text { or } 3 x=-4 y-1=\lambda(\text { say }) \\

& x=\frac{\lambda}{3}, y=\frac{\lambda+1}{-4}

\end{aligned}

\)

Putting these values in \(x+y-z-3=0\), we have \(\frac{\lambda}{3}+\frac{\lambda+1}{-4}-z-3=0\)

\(

\lambda=39+12 z

\)

Comparing values of \(\lambda\), we have equation of line as

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 3 x=-4 y-1=12 z+39 \\

& \frac{3 x}{12}=\frac{-4 y-1}{12}=\frac{12 z+39}{12} \text { or } \frac{x}{4}=\frac{y+\frac{1}{4}}{-3}=\frac{z+\frac{13}{4}}{1}

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the line is passing through point \(\left(0,-\frac{1}{4},-\frac{13}{4}\right)\) and have direction ratios \(4,-3,1\).

If we eliminate \(x\) or \(y\) first we will get equation of line having same direction ratio but with different point on the line.

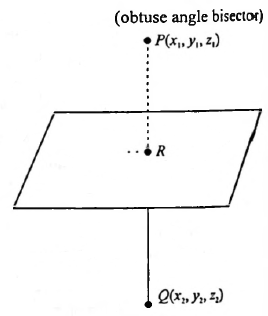

Example 9: If \(\vec{r}=(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k})+\lambda(\hat{i}-\hat{j}+\hat{k})\) and \(\vec{r}=(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k})+\mu(\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k})\) are two lines, then find the equation of acute angle bisector of two lines.

Solution: Solution: The direction vectors of the two given lines are identified.

The direction vector of the first line is \(\overrightarrow{b_1}=\hat{i}-\hat{j}+\hat{k}\).

The direction vector of the second line is \(\overrightarrow{b_2}=\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k}\).

The cosine of the angle between the lines is determined.

\(

\cos \theta=\frac{\overrightarrow{b_1} \cdot \overrightarrow{b_2}}{\left|\overrightarrow{b_1}\right|\left|\overrightarrow{b_2}\right|}=\frac{-1}{\sqrt{3} \cdot \sqrt{3}}=\frac{-1}{3} .

\)

Since \(\cos \theta\) is negative, the angle \(\theta\) is obtuse. The acute angle between the lines is \(\pi-\theta\).

The direction vectors for the angle bisectors are found using the formula

\(

\frac{\overrightarrow{b_1}}{\left|\overrightarrow{b_1}\right|} \pm \frac{\overrightarrow{b_2}}{\left|\overrightarrow{b_2}\right|}

\)

The direction vector for one bisector is

\(

\vec{d}_1=\frac{\hat{i}-\hat{j}+\hat{k}}{\sqrt{3}}+\frac{\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k}}{\sqrt{3}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}((\hat{i}-\hat{j}+\hat{k})+(\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k}))=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}(2 \hat{i})

\)

The direction vector for the other bisector is

\(

\vec{d}_2=\frac{\hat{i}-\hat{j}+\hat{k}}{\sqrt{3}}-\frac{\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k}}{\sqrt{3}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}((\hat{i}-\hat{j}+\hat{k})-(\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k}))=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}(-2 \hat{j}+2 \hat{k})

\)

Identifying the Acute Angle Bisector:

The dot product of \(\vec{b}_1\) and \(\vec{d}_1\) is calculated to determine if \(\vec{d}_1\) corresponds to the acute or obtuse angle bisector.

\(

\vec{b}_1 \cdot \vec{d}_1=(\hat{i}-\hat{j}+\hat{k}) \cdot\left(\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}} \hat{i}\right)=\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}} .

\)

Since \(\vec{b}_1 \cdot \vec{d}_1>0\), the angle between \(\vec{b}_1\) and \(\vec{d}_1\) is acute. Therefore, \(\vec{d}_1\) is the direction vector of the obtuse angle bisector because the angle between the original lines is obtuse.

The direction vector of the acute angle bisector is \(\vec{d}_2=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}(-2 \hat{j}+2 \hat{k})\). This can be simplified to \(\hat{j}-\hat{k}\) by taking out a common factor of \(\frac{-2}{\sqrt{3}}\).

Equation of the Acute Angle Bisector:

The equation of the acute angle bisector is formed using the common point of intersection of the two lines and the direction vector of the acute angle bisector.

The common point of intersection is \((\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k})\).

The equation of the acute angle bisector is \(\vec{r}=(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k})+\lambda(\hat{j}-\hat{k})\).

Example 10: Find the equation of the line drawn through point \((1,0,2)\) to meet the line \(\frac{x+1}{3}=\frac{y-2}{-2} =\frac{z+1}{-1}\) at right angles.

Solution: Given line is \(\overrightarrow{A B} \equiv \frac{x+1}{3}=\frac{y-2}{-2}=\frac{z+1}{-1} \dots(i)\)

Let \(P \equiv(1,0,2)\)

Any point on line (i) is \(Q \equiv(3 r-1,-2 r+2,-r-1)\)

Direction ratios of \(P Q\) are \(3 r-2,-2 r+2,-r-3\)

Direction ratios of line \(A B\) are \(3,-2,-1\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\because & P Q \perp A B \\

\therefore & 3(3 r-2)-2(-2 r+2)-1(-r-3)=0 \\

\text { or } & 14 r=7 \text { or } r=\frac{1}{2}

\end{array}

\)

Therefore, direction ratios of \(P Q\) are \(-\frac{1}{2}, 1,-\frac{7}{2}\) or \(1,-2 ; 7\)

Equation of line \(P Q \equiv \frac{x-1}{1}=\frac{y}{-2}=\frac{z-2}{7}\)

Example 11: Line \(L_1\) is parallel to vector \(\bar{\alpha}=-3 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+4 \hat{k}\) and passes through a point \(A(7,6,2)\) and line \(L_2\) is parallel to a vector \(\vec{\beta}=2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+3 \hat{k}\) and passes through a point \(B(5,3,4)\). Now a line \(L_3\) parallel to a vector \(\vec{r}=2 \hat{i}-2 \hat{j}-\hat{k}\) intersects the lines \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) at points \(C\) and \(D\), respectively, then find \(|\overline{C D}|\).

Solution: Line \(L_1\) is parallel to vector \(\vec{\alpha}=-3 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+4 \hat{k}\) and passes through a point \(A(7,6,2)\).

Therefore, position vector of any point on the line is \(7 \hat{i}+6 \hat{j}+2 \hat{k}+\lambda(-3 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+4 \hat{k})\); line \(L_2\) is parallel to a vector \(\vec{\beta}=2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+3 \hat{k}\) and passes through a point \(B(5,3,4)\).

Position vector of any point on the line \(5 \hat{i}+3 \hat{j}+4 \hat{k}+\mu(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+3 \hat{k})\)

\(

\therefore \quad \overline{C D}=2 \hat{i}+3 \hat{j}-2 \hat{k}+\lambda(-3 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+4 \hat{k})-\mu(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+3 \hat{k})

\)

Since it is parallel to \(2 \hat{i}-2 \hat{j}-\hat{k}\), we have

\(

\frac{2-3 \lambda-2 \mu}{2}=\frac{3+2 \lambda-\mu}{-2}=\frac{-2+4 \lambda-3 \mu}{-1}

\)

Solving these equations we get \(\lambda=2\) and \(\mu=1\). Therefore, or

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \overrightarrow{C D}=-6 \hat{i}+6 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k} \\

& |\overrightarrow{C D}|=9

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 12: Find the coordinates of a point on the line \(\frac{x-1}{2}=\frac{y+1}{-3}=z\) at a distance \(4 \sqrt{14}\) from the point \((1,-1,0)\).

Solution: The given line equation is \(\frac{x-1}{2}=\frac{y+1}{-3}=z\). This equation can be set equal to a parameter, say \(\lambda\), to express the coordinates of any point on the line in terms of \(\lambda\).

Thus, \(x-1=2 \lambda, y+1=-3 \lambda\), and \(z=\lambda\).

The coordinates of a general point on the line are given by

\(

(x, y, z)=(1+2 \lambda,-1-3 \lambda, \lambda)

\)

The distance between a point \(\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right)\) and another point \(\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\) is given by the formula \(D=\sqrt{\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2+\left(z_2-z_1\right)^2}\).

In this case, the point on the line is \((1+2 \lambda,-1-3 \lambda, \lambda)\) and the given point is \((1,-1,0)\). The distance is given as \(4 \sqrt{14}\).

Substituting these values into the distance formula:

\(

4 \sqrt{14}=\sqrt{((1+2 \lambda)-1)^2+((-1-3 \lambda)-(-1))^2+(\lambda-0)^2} .

\)

This simplifies to \(4 \sqrt{14}=\sqrt{(2 \lambda)^2+(-3 \lambda)^2+(\lambda)^2}\).

Squaring both sides of the equation:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (4 \sqrt{14})^2=(2 \lambda)^2+(-3 \lambda)^2+(\lambda)^2 \\

& 16 \times 14=4 \lambda^2+9 \lambda^2+\lambda^2 \\

& 224=14 \lambda^2

\end{aligned}

\)

Dividing both sides by 14:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \lambda^2=\frac{224}{14} . \\

& \lambda^2=16 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Taking the square root of both sides:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \lambda= \pm \sqrt{16} . \\

& \lambda= \pm 4 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Substitute the values of \(\lambda\) back into the parameterized coordinates of the point on the line, \((1+2 \lambda,-1-3 \lambda, \lambda)\).

Case 1: For \(\lambda=4\) :

The coordinates are \((1+2(4),-1-3(4), 4)=(1+8,-1-12,4)=(9,-13,4)\).

Case 2: For \(\lambda=-4\) :

The coordinates are

\(

(1+2(-4),-1-3(-4),-4)=(1-8,-1+12,-4)=(-7,11,-4)

\)

The coordinates of the points on the line at a distance \(4 \sqrt{14}\) from the point \((1,-1,0)\) are \((9,-13,4)\) and \((-7,11,-4)\).

ANGLE BETWEEN TWO LINES

Let the given lines be

\(

\left.\begin{array}{l}

\vec{r}=\vec{a}+\lambda \vec{b} \quad \text { (i) } \\

\vec{r}=\overrightarrow{a^{\prime}}+\lambda \overrightarrow{b^{\prime}} \quad \text { (ii) }

\end{array}\right\} \rightarrow \text { Vector form }

\)

\(

\left.\begin{array}{l}

\frac{x-a_1}{b_1}=\frac{y-a_2}{b_2}=\frac{z-a_3}{b_3} \\

\frac{x-a_1^{\prime}}{b_1^{\prime}}=\frac{y-a_2^{\prime}}{b_2^{\prime}}=\frac{z-a_3^{\prime}}{b_3^{\prime}}

\end{array}\right\} \rightarrow \text { Cartesian form }

\)

Clearly (i) and (ii) are straight lines in the directions of \(\vec{b}\) and \(\overrightarrow{b^{\prime}}\), respectively.

Let \(\theta\) be the angle between the straight lines (i) and (ii).

Then \(\theta\) is the angle between vectors \(\vec{b}\) and \(\overrightarrow{b^{\prime}}\). Therefore,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \cos \theta=\frac{\vec{b} \cdot \overrightarrow{b^{\prime}}}{|\vec{b}|\left|\overrightarrow{b^{\prime}}\right|} \\

& \vec{b}=b \hat{i}+b_2 \hat{j}+b_3 \hat{k}, \overrightarrow{b^{\prime}}=b_1^{\prime} \hat{i}+b_2^{\prime} \hat{j}+b_3^{\prime} \hat{k} \\

& \vec{b} \cdot \overrightarrow{b^{\prime}}=b_1 b_1^{\prime}+b_2 b_2^{\prime}+b_3 b_3^{\prime}

\end{aligned}

\)

and \(|\vec{b}|=\sqrt{b_1^2+b_2^2+b_3^3},\left|\overrightarrow{b^{\prime}}\right|=\sqrt{b_1^{\prime 2}+b_2^{\prime 2}+b_3^{\prime 2}}\)

\(

\cos \theta=\frac{b_1 b_1^{\prime}+b_2 b_2^{\prime}+b_3 b_3^{\prime}}{\sqrt{b_1^2+b_2^2+b_3^3} \sqrt{b_1^2+b_2^{\prime 2}+b_3^{\prime 2}}}

\)

Notes:

- If the lines are perpendicular, then \(\vec{b} \cdot \overrightarrow{b^{\prime}}=0 \Rightarrow b_1 b_1^{\prime}+b_2 b_2^{\prime}+b_3 b_3^{\prime}=0\).

- If the lines are parallel, then \(\vec{b}=\lambda \overrightarrow{b^{\prime}}\) for some scalar \(\lambda \Rightarrow \frac{b_1}{b_2^{\prime}}=\frac{b_2}{b_2^{\prime}}=\frac{b_3}{b_3^{\prime}}\).

Example 13: Find the angle between the following pair of lines:

i. \(\vec{r}=2 \hat{i}-5 \hat{j}+\hat{k}+\lambda(3 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+6 \hat{k})\) and \(\vec{r}=7 \hat{i}-6 \hat{k}+\mu(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+2 \hat{k})\)

ii. \(\frac{x}{2}=\frac{y}{2}=\frac{z}{1}\) and \(\frac{x-5}{4}=\frac{y-2}{1}=\frac{z-3}{8}\)

Solution: (i) The given lines are parallel to the vectors \(\vec{b}_1=3 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+6 \hat{k}\) and \(\vec{b}_2=\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+2 \hat{k}\), respectively. If \(\theta\) is the angle between the given pair of lines, then

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \cos \theta=\frac{\vec{b}_1 \cdot \vec{b}_2}{\left|\vec{b}_1\right|\left|\vec{b}_2\right|}=\frac{(3)(1)+(2)(2)+(6)(2)}{\sqrt{3^2+2^2+6^2} \sqrt{1^2+2^2+2^2}}=\frac{19}{7 \times 3} \\

& \theta=\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{19}{21}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

(ii) The given lines are parallel to the vectors \(\vec{b}_1=2 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+\hat{k}\) and \(\vec{b}_2=4 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+8 \hat{k}\), respectively. If \(\theta\) is the angle between the given pair of lines, then

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \cos \theta=\frac{\vec{b}_1 \cdot \vec{b}_2}{\left|\vec{b}_1\right|\left|\vec{b}_2\right|}=\frac{(2)(4)+(2)(1)+(1)(8)}{\sqrt{2^2+2^2+1^2} \sqrt{4^2+1^2+8^2}}=\frac{18}{3 \times 9}=\frac{2}{3} \\

& \theta=\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 14: Find the values of \(p\) so that line \(\frac{1-x}{3}=\frac{7 y-14}{2 p}=\frac{z-3}{2}\) and \(\frac{7-7 x}{3 p}=\frac{y-5}{1}=\frac{6-z}{5}\) are at right angles.

Solution: The given equations can be written in the standard form as

\(

\frac{x-1}{-3}=\frac{y-2}{2 p / 7}=\frac{z-3}{2} \text { and } \frac{x-1}{-3 p / 7}=\frac{y-5}{1}=\frac{z-6}{-5}

\)

The direction ratios of the lines are \(-3, \frac{2 p}{7} ; 2\) and \(\frac{-3 p}{7}, 1,-5\), respectively. Lines are perpendicular to each other. Therefore,

\(

(-3) \cdot\left(\frac{-3 p}{7}\right)+\left(\frac{2 p}{7}\right) \cdot(1)+2 \cdot(-5)=0

\)

\(

\frac{9 p}{7}+\frac{2 p}{7}=10 \text { or } 11 p=70 \text { or } p=\frac{70}{11}

\)

Example 15: Find the acute angle between the lines \(\frac{x-1}{\ell}=\frac{y+1}{m}=\frac{z}{n}\) and \(\frac{x+1}{m}=\frac{y-3}{n}=\frac{z-1}{\ell}\), where \(\ell>m>n\), and \(\ell, m, n\) are the roots of the cubic equation \(x^3+x^2-4 x=4\).

Solution: Given lines are \(\frac{x-1}{\ell}=\frac{y+1}{m}=\frac{z}{n}\) and \(\frac{x+1}{m}=\frac{y-3}{n}=\frac{z-1}{\ell}\) Angle between lines is given by

\(

\cos \theta=\frac{\ell m+m n+n \ell}{\ell^2+m^2+n^2}

\)

Now \(\ell, m, n\) are the roots of the cubic equation \(x^3+x^2-4 x=4\). Thus,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \ell+m+n=-1 \text { and } \ell m+m n+n \ell=-4 \\

& (\ell+m+n)^2=\ell^2+m^2+n^2+2(\ell m+m n+n \ell) \\

& (-1)^2=\ell^2+m^2+n^2+2(-4) \\

& \ell^2+m^2+n^2=9 \\

& \cos \theta=-\frac{4}{9}

\end{aligned}

\)

Therefore, acute angle between the lines is \(\cos ^{-1} \frac{4}{9}\).

Example 16: Find the condition if lines \(x=a y+b, z=c y+d\) and \(x=a^{\prime} y+b^{\prime}, z=c^{\prime} y+d\) are perpendicular.

Solution: The equations of straight lines can be rewritten as

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=a y+b, z=c y+d \Rightarrow \frac{x-b}{a}=\frac{y-0}{1}=\frac{z-d}{c} \\

& x=a^{\prime} y+b^{\prime}, z=c^{\prime} y+d \Rightarrow \frac{x-b^{\prime}}{a^{\prime}}=\frac{y-0}{1}=\frac{z-d^{\prime}}{c^{\prime}}

\end{aligned}

\)

The above lines are perpendicular if \(a a^{\prime}+1 \cdot 1+c \cdot c^{\prime}=0\).

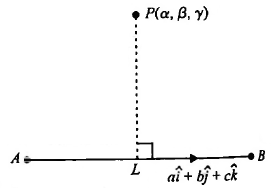

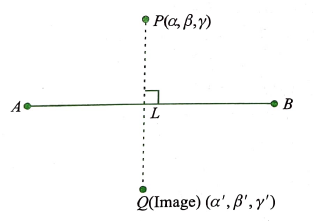

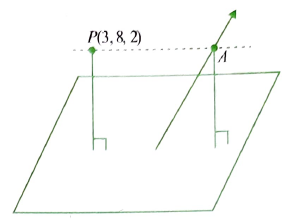

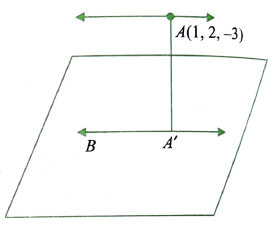

PERPENDICULAR DISTANCE OF A POINT FROM A LINE

Foot of Perpendicular from a Point on the Given Line

Cartesian form

Here, the equation of line \(A B\) is \(\frac{x-x_1}{a}=\frac{y-y_1}{b}=\frac{z-z_1}{c}\).

Let \(L\) be the foot of the perpendicular drawn from \(P(\alpha, \beta, \gamma)\) on the line \(\frac{x-x_1}{a}=\frac{y-y_1}{b}=\frac{z-z_1}{c}\).

Let the coordiantes of \(L\) be \(\left(x_1+a \lambda, y_1+b \lambda, z_1+c \lambda\right)\).

Then the direction ratios of \(P L\) are \(\left(x_1+a \lambda-\alpha, y_1+b \lambda-\beta, z_1+c \lambda-\gamma\right)\).

Direction ratios of \(A B\) are \((a, b, c)\).

Since \(P L\) is perpendicular to \(A B\),

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a\left(x_1+a \lambda-\alpha\right)+b\left(y_1+b \lambda-\beta\right)+c\left(z_1+c \lambda-\gamma\right)=0 \\

& \lambda=\frac{a\left(\alpha-x_1\right)+b\left(\beta-y_1\right)+c\left(\gamma-z_1\right)}{a^2+b^2+c^2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Putting the value of \(\lambda\) in ( \(x_1+a \lambda, y_1+b \lambda, z_1+c \lambda\) ), we get the foot of the perpendicular. Now we can get distance \(P L\) using the distance formula.

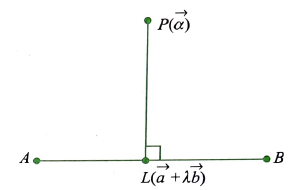

Vector form

Let \(L\) be the foot of the perpendicular drawn from \(P(\vec{\alpha})\) on the line \(\vec{r}=\vec{a}+\lambda \vec{b}\).

Since \(\vec{r}\) denotes the position vector of any point on the line \(\vec{r}=\vec{a}+\lambda \vec{b}\), the position vector of \(L\) will be \((\vec{a}+\lambda \vec{b})\)

Directions ratios of \(P L=\vec{a}-\vec{\alpha}+\lambda \vec{b}\)

Since \(\overrightarrow{P L}\) is perpendicular to \(\vec{b}\), we have

\(

(\vec{a}-\vec{\alpha}+\lambda \vec{b}) \cdot \vec{b}=0

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (\vec{a}-\vec{\alpha}) \cdot \vec{b}+\lambda \vec{b} \cdot \vec{b}=0 \\

& \lambda=\frac{-(\vec{a}-\vec{\alpha}) \cdot \vec{b}}{|\vec{b}|^2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus, position vector of \(L\) is \(\vec{a}-\left(\frac{(\vec{a}-\vec{\alpha}) \cdot \vec{b}}{|\vec{b}|^2}\right) \vec{b}\), which is the foot of the perpendicular.

Image of a Point in the Given Line

Since \(L\) (foot of perpendicular) is the midpoint of \(P\) and \(Q\) (image of a point \(P\) in the line), we can get \(Q\) if \(L\) is found out.

Example 17: Find the coordinates of the foot of the perpendicular drawn from point \(\lambda(1,0,3)\) to the join of points \(B(4,7,1)\) and \(C(3,5,3)\).

Solution: Let \(D\) be the foot of the perpendicular and let it divide \(B C\) in the ratio \(\lambda: 1\). Then the coordinates of \(D\) are \(\frac{3 \lambda+4}{\lambda+1}, \frac{5 \lambda+7}{\lambda+1}\) and \(\frac{3 \lambda+1}{\lambda+1}\).

Now,

\(

\overrightarrow{A D} \perp \overrightarrow{B C} \Rightarrow \overrightarrow{A D} \cdot \overrightarrow{B C}=0

\)

\(\Rightarrow (2 \lambda+3)+2(5 \lambda+7)+4=0\)

\(

\lambda=-\frac{7}{4}

\)

Thus, coordinates of \(D\) are \(\frac{5}{3}, \frac{7}{3}\) and \(\frac{17}{3}\).

Example 18: Find the length of the perpendicular drawn from point \((2,3,4)\) to line \(\frac{4-x}{2}=\frac{y}{6}=\frac{1-z}{3}\).

Solution: Let \(P\) be the foot of the perpendicular from \(A(2,3,4)\) to the given line \(l\) whose equation is

\(

\frac{4-x}{2}=\frac{y}{6}=\frac{1-z}{3} \quad \text { or } \quad \frac{x-4}{-2}=\frac{y}{6}=\frac{z-1}{-3}=k \text { (say) } \dots(i)

\)

\(

x=4-2 k, y=6 k, z=1-3 k

\)

As \(P\) lies on (i), coordinates of \(P\) are \((4-2 k, 6 k, 1-3 k)\) for some value of \(k\).

The direction ratios of \(A P\) are

\(

(4-2 k-2,6 k-3,1-3 k-4) \text { or }(2-2 k, 6 k-3,-3-3 k)

\)

Also, the direction ratios of \(l\) are \(-2,6\) and -3.

Since \(A P \perp l\), we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& -2(2-2 k)+6(6 k-3)-3(-3-3 k)=0 \\

& -4+4 k+36 k-18+9+9 k=0 \text { or } 49 k-13=0 \text { or } k=13 / 49

\end{aligned}

\)

We have \(\quad A P^2=(4-2 k-2)^2+(6 k-3)^2+(1-3 k-4)^2\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =(2-2 k)^2+(6 k-3)^2+(-3-3 k)^2 \\

& =4-8 k+4 k^2+36 k^2-36 k+9+9+18 k+9 k^2 \\

& =22-26 k+49 k^2 \\

& =22-26\left(\frac{13}{49}\right)+49\left(\frac{13}{49}\right)^2 \\

& =\frac{22 \times 49-26 \times 13+13^2}{49}=\frac{909}{49} \\

A P & =\frac{3}{7} \sqrt{101}

\end{aligned}

\)

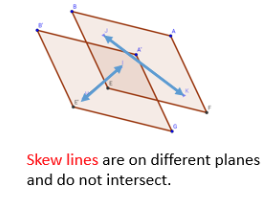

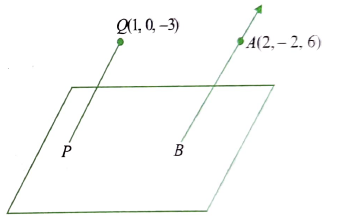

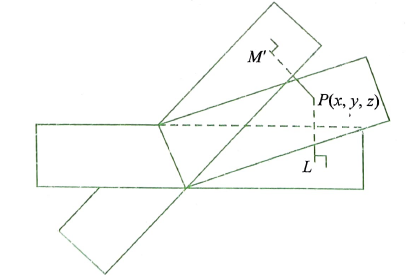

SHORTEST DISTANCE BETWEEN TWO LINES

If two lines in space intersect at a point, then the shortest distance between them is zero. Also, if two lines in space are parallel, then the shortest distance between them will be the perpendicular distance, i.e., the length of the perpendicular drawn from any point on one line onto the other line. Further. in a space, there are lines which are neither intersecting nor parallel. In fact, such pair of lines are non-coplanar and are called skew lines.

Line \(G E\) goes diagonally across the ceiling and line \(D B\) passes through one comer of the ceiling directly above \(A\) and goes diagonally down the wall. These lines are skew because they are not parallel and also never meet.

By the shortest distance between two lines, we mean the join of a point in one line with one point on the other line so that the length of the segment so obtained is the smallest. For skew lines, the line of the shortest distance will be perpendicular to both the lines.

Note: Non-coplanar lines are lines that do not lie in the same plane. They are also referred to as skew lines if they do not intersect. In other words, if you have two or more lines that are not situated on a single flat surface, they are considered non-coplanar.

Shortest Distance between Two Non-coplanar Lines

Vector form

Let the given lines be \(\vec{r}=\vec{a}+t \vec{b}\) and \(\vec{r}=\vec{c}+t_1 \vec{d}\).

If two lines \(A B\) and \(C D\) do not intersect, there is always a line intersecting both the lines perpendicularly.

The intercept on this line made by \(A B\) and \(C D\) is called the shortest distance between lines \(A B\) and \(C D\).

In Figure above, the shortest distance \(=L M\), where \(\angle A L M=\angle C M L=90^{\circ}\). In the figure, the shortest distance

\(

\begin{aligned}

L M & =\mid \text { Projection of } \overrightarrow{A C} \text { along } \overrightarrow{M L} \mid \\

& =\left|\overrightarrow{A C} \cdot \frac{\overrightarrow{M L}}{|\overrightarrow{M L}|}\right|=\frac{|(\vec{a}-\vec{c}) \cdot \overrightarrow{L M}|}{|\overrightarrow{L M}|}

\end{aligned}

\)

Now \(\overrightarrow{L M}\) is perpendicular to both \(\vec{b}\) and \(\vec{d}\). Thus,

\(

\begin{aligned}

\overrightarrow{L M} & =\vec{b} \times \vec{d} \\

& =\frac{|(\vec{a}-\vec{c}) \cdot(\vec{b} \times \vec{d})|}{|\vec{b} \times \vec{d}|} \\

& =\frac{|[\vec{b} \vec{d} \vec{a}-\vec{c}]|}{|\vec{b} \times \vec{d}|}

\end{aligned}

\)

Cartesian form

Let the two skew lines be \(\frac{x-a_1}{b_1}=\frac{y-a_2}{b_2}=\frac{z-a_3}{b_3}\) and \(\frac{x-c_1}{d_1}=\frac{y-c_2}{d_2}=\frac{z-c_3}{d_3}\)

\(

\text { Then Shortest distance }=\frac{\left\|\begin{array}{ccc}

c_1-a_1 & c_2-a_2 & c_3-a_3 \\

b_1 & b_2 & b_3 \\

d_1 & d_2 & d_3

\end{array}\right\|}{\left\|\begin{array}{ccc}

\hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\

b_1 & b_2 & b_3 \\

d_1 & d_2 & d_3

\end{array}\right\|}

\)

Condition for Lines to Intersect

Two lines \(\vec{r}=\vec{a}+t \vec{b}\) and \(\vec{r}=\vec{c}+t_1 \vec{d}\) are intersecting if

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left|\frac{(\vec{a}-\vec{c}) \cdot(\vec{b}-\vec{d})}{\vec{b} \times \vec{d}}\right|=0 \\

& \left|\begin{array}{ccc}

c_1-a_1 & c_2-a_2 & c_3-a_3 \\

b_1 & b_2 & b_3 \\

d_1 & d_2 & d_3

\end{array}\right|=0

\end{aligned}

\)

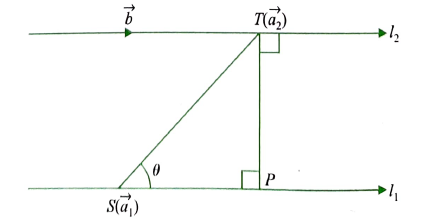

Distance between Two Parallel Lines

If two lines \(l_1\) and \(l_2\) are parallel, then they are coplanar. Let the lines be given by

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \vec{r}=\overrightarrow{a_1}+\lambda \vec{b} \dots(i) \\

& \vec{r}=\overrightarrow{a_2}+\mu \vec{b} \dots(ii)

\end{aligned}

\)

where \(\vec{a}_1\) is the position vector of a point \(S\) on \(l_1\) and \(\vec{a}_2\) is the position vector of a point \(T\) on \(l_2\).

As \(l_1\) and \(l_2\) are coplanar. if the foot of the perpendicular from \(T\) on iine \(l_1\) is \(P\), then the distance between the lines \(l_1\) and \(l_2=|T P|\).

Let \(\theta\) be the angle between vectors \(\overrightarrow{S T}\) and \(\vec{b}\).

Then \(\vec{b} \times \overrightarrow{S T}=(|\vec{b}||\overrightarrow{S T}| \sin \theta) \hat{n} \dots(iii)\)

where \(\hat{n}\) is the unit vector perpendicular to the plane of the lines \(l_1\) and \(l_2\).

But \(\quad \overrightarrow{S T}=\vec{a}_2-\vec{a}_1\)

Therefore, from (iii), we get

\(

\vec{b} \times\left(\vec{a}_2-\vec{a}_1\right)=|\vec{b}| ~P T~ \hat{n} \text { (since } P T=S T \sin \theta \text { ) }

\)

i.e., \(\left|\vec{b} \times\left(\overrightarrow{a_2}-\overrightarrow{a_1}\right)\right|=|\vec{b}| P T \cdot 1 (\text { as }|\hat{n}|=1)\)

Hence, the distance between the given parallel lines is

\(

d=|\overrightarrow{P T}|=\left|\frac{\vec{b} \times\left(\vec{a}_2-\vec{a}_1\right)}{|\vec{b}|}\right|

\)

Example 19: Find the shortest distance between the lines \(\frac{x-1}{2}=\frac{y-2}{3}=\frac{z-3}{4}\) and \(\frac{x-2}{3}=\frac{y-4}{4} =\frac{z-5}{5}\). Also obtain the equation of the line of the shortest distance.

Solution: (i) The two given lines are \(\frac{x-1}{2}=\frac{y-2}{3}=\frac{z-3}{4}=r_1 \text { (say) } \dots(i)\)

\(

\frac{x-2}{3}=\frac{y-4}{4}=\frac{z-5}{5}=r_2(\mathrm{say}) \dots(ii)

\)

Any point on (i) is given by \(P\left(2 r_1+1,3 r_1+2,4 r_1+3\right)\)

And any point on (ii) is given by \(Q\left(3 r_2+2,4 r_2+4,5 r_2+5\right)\)

Direction ratios of \(P Q\) are given by \(3 r_2-2 r_1+1,4 r_2-3 r_1+2\) and \(5 r_2-4 r_1+2\)

Since \(P Q\) is perpendicular to (i), we get

\(

2\left(3 r_2-2 r_1+1\right)+3\left(4 r_2-3 r_1+2\right)+4\left(5 r_2-4 r_1+2\right)=0

\)

\(

38 r_2-29 r_1+16=0 \dots(iii)

\)

Also \(P Q\) is perpendicular to (ii), we get

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 3\left(3 r_2-2 r_1+1\right)+4\left(4 r_2-3 r_1+2\right)+5\left(5 r_2-4 r_1+2\right)=0 \\

& 50 r_2-38 r_1+21=0 \dots(iv)

\end{aligned}

\)

Solving (iii) and (iv), we obtain \(r_2=-(1 / 6), r_1=(1 / 3)\).

Therefore, coordinates of \(P\) and \(Q\) are \(\left(\frac{5}{3}, 3, \frac{13}{3}\right)\) and \(\left(\frac{3}{2}, \frac{10}{3}, \frac{25}{6}\right)\), respectively. Thus,

\(

P Q^2=\left(\frac{3}{2}-\frac{5}{3}\right)^2+\left(\frac{10}{3}-3\right)^2+\left(\frac{25}{6}-\frac{13}{3}\right)^2=\left(-\frac{1}{6}\right)^2+\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^2+\left(-\frac{1}{6}\right)^2=\frac{1}{6}

\)

\(P Q=\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}\)

The equation of the line of the shortest distance is given by

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{x-(5 / 3)}{(3 / 2)-(5 / 3)}=\frac{y-3}{(10 / 3)-3}=\frac{z-(13 / 3)}{(25 / 6)-(13 / 3)} \\

& \frac{x-(5 / 3)}{-(1 / 6)}=\frac{y-3}{(1 / 3)}=\frac{z-(13 / 3)}{-(1 / 6)} \\

& \frac{x-(5 / 3)}{1}=\frac{y-3}{-2}=\frac{z-(13 / 3)}{1}

\end{aligned}

\)

Alternative method for finding the shortest distance:

Line (i) is passing through the point \(\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right) \equiv(1,2,3)\) and is parallel to vector

\(

a_1 \hat{i}+b_1 \hat{j}+c_1 \hat{k} \equiv 2 \hat{i}+3 \hat{j}+4 \hat{k}

\)

Line (ii) is passing through the point \(\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right) \equiv(2,4,5)\) and is parallel to the vector

\(

a_2 \hat{i}+b_2 \hat{j}+c_2 \hat{k} \equiv 3 \hat{i}+4 \hat{j}+5 \hat{k}

\)

Hence, the shortest distance between the lines using the formula

\(

\frac{\left\|\begin{array}{ccc}

x_2-x_1 & y_2-y_1 & z_2-z_1 \\

a_1 & b_1 & c_1 \\

a_2 & b_2 & c_2

\end{array}\right\|}{\left\|\begin{array}{ccc}

\hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\

a_1 & b_1 & c_1 \\

a_2 & b_2 & c_2

\end{array}\right\|}

\)

is

\(

\frac{\left\|\begin{array}{ccc}

2-1 & 4-2 & 5-3 \\

2 & 3 & 4 \\

3 & 4 & 5

\end{array}\right\|}{\left\|\begin{array}{ccc}

\hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\

2 & 3 & 4 \\

3 & 4 & 5

\end{array}\right\|}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}

\)

Example 20: Determine whether the following pair of lines intersect or not.

i. \(\vec{r}=\hat{i}-\hat{j}+\lambda(2 \hat{i}+\hat{k}) ; \vec{r}=2 \hat{i}-\hat{j}+\mu(\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k})\)

ii. \(\quad \vec{r}=\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k}+\lambda(3 \hat{i}-\hat{j}) ; \vec{r}=4 \hat{i}-\hat{k}+\mu(2 \hat{i}+3 \hat{k})\)

Solution: (i) Here \(\vec{a}_1=\hat{i}-\hat{j}, \vec{a}_2=2 \hat{i}-\hat{j}, \vec{b}_1=2 \hat{i}+\hat{k}\)

and \(\vec{b}_2=\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Now }\\

&\begin{aligned}

{\left[\overrightarrow{a_2}-\overrightarrow{a_1} \vec{b}_1 \vec{b}_2\right] } & =\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

2-1 & -1+1 & 0 \\

2 & 0 & 1 \\

1 & 1 & -1

\end{array}\right| \\

& =\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 0 & 0 \\

2 & 0 & 1 \\

1 & 1 & -1

\end{array}\right| \\

& =-1 \neq 0

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus, the two given lines do not intersect.

(ii) Here \(\overrightarrow{a_1}=\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k}, \overrightarrow{a_2}=4 \hat{i}-\hat{k}, \overrightarrow{b_1}=3 \hat{i}-\hat{j}\)

and \(\overrightarrow{b_2}=2 \hat{i}+3 \hat{k}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\Rightarrow \quad\left[\vec{a}_2-\vec{a}_1 \vec{b}_1 \vec{b}_2\right] & =\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

4-1 & 0-1 & -1+1 \\

3 & -1 & 0 \\

2 & 0 & 3

\end{array}\right| \\

& =\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

3 & -1 & 0 \\

3 & -1 & 0 \\

2 & 0 & 3

\end{array}\right|=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus, the two given lines intersect. Let us obtain the point of intersection of the two given lines.

For some values of \(\lambda\) and \(\mu\), the two values of \(\vec{r}\) must coincide. Thus,

\(

\hat{i}+\hat{j}-\hat{k}+\lambda(3 \hat{i}-\hat{j})=4 \hat{i}-\hat{k}+\mu(2 \hat{i}+3 \hat{k})

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (3+2 \mu-3 \lambda) \hat{i}+(\lambda-1) \hat{j}+3 \mu \hat{k}=0 \\

& 3+2 \mu-3 \lambda=0, \lambda-1=0,3 \mu=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Solving, we obtain \(\lambda=1\) and \(\mu=0\)

Therefore, the point of intersection is \(\vec{r}=4 \hat{i}-\hat{k}\) (by putting \(\mu=0\) in the second equation).

Example 21: Find the shortest distance between lines \(\vec{r}=(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+\hat{k})+\lambda(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+2 \hat{k})\) and \(\vec{r}=2 \hat{i}-\hat{j}-\hat{k}+\mu(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+2 \hat{k})\).

Solution: Here lines (i) ane (ii) are passing through the points \(\overrightarrow{a_1}=\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+\hat{k}\) and \(\overrightarrow{a_2}=2 \hat{i}-\hat{j}-\hat{k}\), respectively, and are parallel to the vector \(\vec{b}=2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+2 \hat{k}\).

Hence, the distance between the lines using the formula is given by

\(

\frac{\left|\vec{b} \times\left(\vec{a}_2-\vec{a}_1\right)\right|}{|\vec{b}|}=\frac{\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\

2 & 1 & 2 \\

1 & -3 & -2

\end{array}\right|}{3}=\frac{|4 \hat{i}-6 \hat{j}-7 \hat{k}|}{3}=\frac{\sqrt{16+36+49}}{3}=\frac{\sqrt{101}}{3}

\)

Example 22: If the straight lines \(x=-1+s, y=3-\lambda s, z=1+\lambda s\) and \(x=\frac{t}{2}, y=1+t, z=2-t\), with parameters \(s\) and \(t\), respectively, are coplanar, then find \(\lambda\).

Solution: The given lines \(\frac{x+1}{1}=\frac{y-3}{-\lambda}=\frac{z-1}{\lambda}=s\)

\(

\frac{x-0}{1 / 2}=\frac{y-1}{1}=\frac{y-2}{-1}=t

\)

are coplanar if \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}0+1 & 1-3 & 2-1 \\ 1 & -\lambda & \lambda \\ 1 / 2 & 1 & -1\end{array}\right|=0 \quad[latex] or [latex]\quad\left|\begin{array}{ccc}1 & -2 & 1 \\ 1 & -\lambda & \lambda \\ 1 / 2 & 1 & -1\end{array}\right|=0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 1(\lambda-\lambda)+2\left(-1-\frac{\lambda}{2}\right)+1\left(1+\frac{\lambda}{2}\right)=0 \\

& \lambda=-2

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 23: Find the equation of a line which passes through the point \((1,1,1)\) and intersects the lines \(\frac{x-1}{2}=\frac{y-2}{3}=\frac{z-3}{4}\) and \(\frac{x+2}{1}=\frac{y-3}{2}=\frac{z+1}{4}\).

Solution: Any line passing through the point \((1,1,1)\) is \(\frac{x-1}{a}=\frac{y-1}{b}=\frac{z-1}{c} \dots(i)\)

This line intersects the line \(\frac{x-1}{2}=\frac{y-2}{3}=\frac{z-3}{4}\).

If \(a: b: c \neq 2: 3: 4\)

and \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}1-1 & 2-1 & 3-1 \\ a & b & c \\ 2 & 3 & 4\end{array}\right|=0 \Rightarrow \quad a-2 b+c=0 \dots(ii)\)

Again, line (i) intersects line \(\frac{x-(-2)}{1}=\frac{y-3}{2}=\frac{z-(-1)}{4}\).

If \(a: b: c \neq 1: 2: 4\)

and \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}-2-1 & 3-1 & -1-1 \\ a & b & c \\ 1 & 2 & 4\end{array}\right|=0 \Rightarrow \quad 6 a+5 b-4 c=0 \dots(iii)\)

From (ii) and (iii) by cross multiplication, we have \(\frac{a}{8-5}=\frac{b}{6+4}=\frac{c}{5+12}\)

\(

\frac{a}{3}=\frac{b}{10}=\frac{c}{17}

\)

So, the required line is \(\frac{x-1}{3}=\frac{y-1}{10}=\frac{z-1}{17}\)

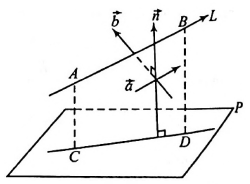

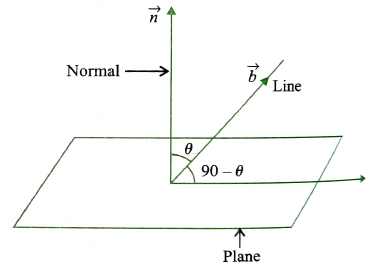

PLANE IN SPACE

A plane is a surface such that if any two points are taken on it, the line segment joining them lies completely on the surface.

A plane is determined uniquely if:

- The normal to the plane and its distance from the origin is given, i.e., the equation of a plane in normal form.

- It passes through a point and is perpendicular to a given direction.

- It passes through three given non-collinear points.

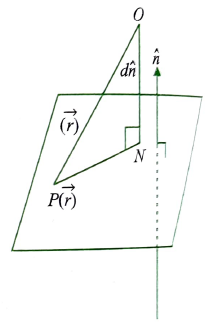

Equation of a Plane in Normal Form

Vector form

Consider a plane whose perpendicular distance from the origin is \(d(d \neq 0)\).

If \(\overrightarrow{O N}\) is the normal from the origin to the plane, and \(\hat{n}\) is the unit normal vector along \(\overrightarrow{O N}\), then \(\overrightarrow{O N}=d \hat{n}\). Let \(P\) be any point on the plane. Therefore, \(\overrightarrow{N P}\) is perpendicular to \(\overrightarrow{O N}\).

\(

\therefore \quad \overrightarrow{N P} \cdot \overrightarrow{O N}=0 \dots(i)

\)

Let \(\vec{r}\) be the position vector of the point \(P\). Then

\(

\overrightarrow{N P}=\vec{r}-d \hat{n}(\text { as } \overrightarrow{O N}+\overrightarrow{N P}=\overrightarrow{O P})

\)

Therefore, (i) becomes

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& (\vec{r}-d \hat{n}) \cdot d \hat{n}=0 \\

\text { or } & (\vec{r}-d \hat{n}) \cdot \hat{n}=0 \quad(d \neq 0) \\

\text { or } & (\vec{r} \cdot \hat{n})-d \hat{n} \cdot \hat{n}=0 \\

\text { or } & \vec{r} \cdot \hat{n}=d \quad \text { (as } \hat{n} \cdot \hat{n}=1) \dots(ii)

\end{array}

\)

This is the vector form of the equation of the plane.

Cartesian form

Equation (ii) gives the vector equation of a plane, where \(\hat{n}\) is the unit vector normal to the plane. Let \(P(x\), \(y, z)\) be any point on the plane. Then

\(

\overrightarrow{O P}=\vec{r}=x \hat{i}+y \hat{j}+z \hat{k}

\)

Let \(l, m\) and \(n\) be the direction cosines of \(\hat{n}\). Then

\(

\hat{n}=\hat{l} \hat{i}+m \hat{j}+n \hat{k}

\)

Therefore, (ii) gives

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (x \hat{i}+y \hat{j}+z \hat{k}) \cdot(l \hat{i}+m \hat{j}+n \hat{k})=d \\

& l x+m y+n z=d \dots(iii)

\end{aligned}

\)

This is the Cartesian equation of the plane in the normal form.

Note: Equation (iii) shows that if \(\vec{r} \cdot(a \hat{i}+b \hat{j}+c \hat{k})=d\) is the vector equation of a plane, then \(a x +b y+c z=d\) is the Cartesian equation of the plane, where \(a, b\) and \(c\) are the direction ratios of the normal to the plane.

Example 24: Find the equation of plane which is at a distance \(\frac{4}{\sqrt{14}}\) from the origin and is normal to vector \(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}-3 \hat{k}\).

Solution: Here \(\vec{n}=2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}-3 \hat{k}\). Then \(\frac{\vec{n}}{|\vec{n}|}=\frac{2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}-3 \hat{k}}{\sqrt{2^2+1^2+(-3)^2}}=\frac{2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}-3 \hat{k}}{\sqrt{14}}\)

Hence, required equation of plane is \(\vec{r} \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{14}}(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}-3 \hat{k})= \pm \frac{1}{\sqrt{14}}\)

\(

\vec{r} \cdot(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}-3 \hat{k})= \pm 1 \text { (vector form) }

\)

\(

2 x+y-3 z= \pm 1(\text { Cartesian form })

\)

Example 25: Find the distance of the plane \(2 x-y-2 z-9=0\) from the origin.

Solution: The distance of a plane \(A x+B y+C z+D=0\) from the origin \((0,0,0)\) is calculated using the formula:

\(

d=\frac{|D|}{\sqrt{A^2+B^2+C^2}}

\)

The given equation of the plane is \(2 x-y-2 z-9=0\).

The coefficients are identified as \(A=2, B=-1, C=-2\), and \(D=-9\).

The absolute value of \(D\) is calculated as \(|-9|=9\).

The square root of the sum of the squares of the coefficients \(A, B\), and \(C\) is calculated as \(\sqrt{2^2+(-1)^2+(-2)^2}=\sqrt{4+1+4}=\sqrt{9}=3\).

The distance \(d\) is calculated by dividing the absolute value of \(D\) by the calculated square root: \(d=\frac{9}{3}=3\).

Example 26: Find the unit vector perpendicular to the plane \(\vec{r} \cdot(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+2 \hat{k})=5\).

Solution: Identifying the Normal Vector:

The equation of a plane is given in the form \(\vec{r} \cdot \vec{n}=d\), where \(\vec{n}\) is the normal vector to the plane.

From the given equation, \(\vec{r} \cdot(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+2 \hat{k})=5\), the normal vector \(\vec{n}\) is identified as \(\vec{n}=2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+2 \hat{k}\).

Calculating the Magnitude of the Normal Vector:

The magnitude of the normal vector \(\vec{n}\) is calculated using the formula \(\|\vec{n}\|=\sqrt{n_x^2+n_y^2+n_z^2}\). Substituting the components of \(\vec{n}\), the magnitude is found as \(\|\vec{n}\|=\sqrt{2^2+1^2+2^2}=\sqrt{4+1+4}=\sqrt{9}=3\).

Finding the Unit Vector:

The unit vector perpendicular to the plane is obtained by dividing the normal vector by its magnitude. The unit vector \(\hat{n}\) is calculated as \(\hat{n}=\frac{\vec{n}}{\|\vec{n}\|}=\frac{2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+2 \hat{k}}{\sqrt{2^2+1^2+2^2}}=\frac{1}{3}(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+2 \hat{k})\).

The unit vector perpendicular to the plane is \(\frac{2}{3} \hat{i}+\frac{1}{3} \hat{j}+\frac{2}{3} \hat{k}\).

Example 27: Find the vector equation of a line passing through \(3 \hat{i}-5 \hat{j}+7 \hat{k}\) and perpendicular to the plane \(3 x-4 y+5 z=8\).

Solution: The line is stated to pass through the point with position vector \(\vec{a}=3 \hat{i}-5 \hat{j}+7 \hat{k}\).

Determine the direction vector of the line:

The line is perpendicular to the plane \(3 x-4 y+5 z=8\). The normal vector to a plane \(A x+B y+C z=D\) is given by \(\vec{n}=A \hat{i}+B \hat{j}+C \hat{k}\). Therefore, the normal vector to the given plane is \(\vec{n}=3 \hat{i}-4 \hat{j}+5 \hat{k}\). Since the line is perpendicular to the plane, its direction vector \(\vec{b}\) will be parallel to the normal vector of the plane. Thus, the direction vector of the line can be taken as \(\vec{b}=3 \hat{i}-4 \hat{j}+5 \hat{k}\).

Formulate the vector equation of the line:

The vector equation of a line passing through a point with position vector \(\vec{a}\) and having a direction vector \(\vec{b}\) is given by \(\vec{r}=\vec{a}+\lambda \vec{b}\), where \(\lambda\) is a scalar parameter. Substituting the identified values, the vector equation of the line is \(\vec{r}=(3 \hat{i}-5 \hat{j}+7 \hat{k})+\lambda(3 \hat{i}-4 \hat{j}+5 \hat{k})\).

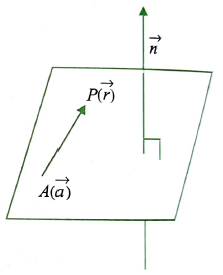

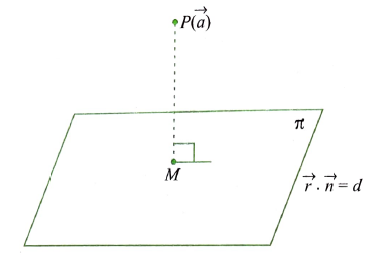

Equation of a Plane Passing through a Given Point and Normal to a Given Vector

Vector Form

Suppose the plane passes through a point having position vector \(\vec{a}\) and is normal to vector \(\vec{n}\).

Then for any position of point \(P(\vec{r})\) on the plane, \(\overrightarrow{A P} \perp \vec{n}\). Thus,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& \overrightarrow{A P} \cdot \vec{n}=0 \\

\text { or } & (\vec{r}-\vec{a}) \cdot \vec{n}=0 \quad(\because \overrightarrow{A P}=\vec{r}-\vec{a})

\end{array}

\)

Hence, the required equation of the plane is \((\vec{r}-\vec{a}) \cdot \vec{n}=0\).

Note: The above equation can be written as \(\vec{r} \cdot \vec{n}=d\), where \(d=\vec{a} \cdot \vec{n}\) (known as scalar product form of plane). The equation \(\vec{r} \cdot \vec{n}=d\) is in normal form if \(\vec{n}\) is a unit vector and \(d\) is the distance of the plane from the origin. If \(\vec{n}\) is not a unit vector, then we reduce the equation \(\vec{r} \cdot \vec{n}=d\) to the normal form by dividing both sides by \(|\vec{n}|\); we get \(\frac{\vec{r} \cdot \vec{n}}{|\vec{n}|}=\frac{d}{|\vec{n}|}\) or \(\vec{r} \cdot \hat{n}=\frac{d}{|n|}=p\) (distance from the origin).

Cartesian Form

If \(\vec{r}=x \hat{i}+y \hat{j}+z \hat{k}, \vec{a}=x_1 \hat{i}+y_1 \hat{j}+z_1 \hat{k}\) and \(\vec{n}=a \hat{i}+b \hat{j}+c \hat{k}\), then

\(

(\vec{r}-\vec{a})=\left(x-x_1\right) \hat{i}+\left(y-y_1\right) \hat{j}+\left(z-z_1\right) \hat{k}

\)

Then equation of the plane can be written as

\(

\left(\left(x-x_1\right) \hat{i}+\left(y-y_1\right) \hat{j}+\left(z-z_1\right) \hat{k}\right) \cdot(a \hat{i}+b \hat{j}+c \hat{k})=0

\)

\(

a\left(x-x_1\right)+b\left(y-y_1\right)+c\left(z-z_1\right)=0

\)

Thus, the coefficients of \(x, y\) and \(z\) in the Cartesian equation of a plane are the direction ratios of the normal to the plane.

Example 28: Find the equation of the plane passing through the point \((2,3,1)\) having \((5,3,2)\) as the direction ratios of the normal to the plane.

Solution: The equation of a plane passing through a point \(\left(x_0, y_0, z_0\right)\) and having direction ratios \((a, b, c)\) of the normal to the plane is given by the formula: \(a\left(x-x_0\right)+b\left(y-y_0\right)+c\left(z-z_0\right)=0\).

The given point on the plane is \(\left(x_0, y_0, z_0\right)=(2,3,1)\).

The given direction ratios of the normal to the plane are \((a, b, c)=(5,3,2)\).

These values are substituted into the general equation of the plane:

\(

5(x-2)+3(y-3)+2(z-1)=0 .

\)

\(

5 x+3 y+2 z=21

\)

Example 29: Find the equation of the plane such that image of point \((1,2,3)\) in it is \((-1,0,1)\).

Solution: Determine the Midpoint of the Segment Connecting the Point and its Image

The plane acts as a mirror, so the midpoint of the line segment connecting the original point \(P_1=(1,2,3)\) and its image \(P_2=(-1,0,1)\) lies on the plane. The coordinates of the midpoint \(M\) are calculated as follows:

\(

M=\left(\frac{1+(-1)}{2}, \frac{2+0}{2}, \frac{3+1}{2}\right)=\left(\frac{0}{2}, \frac{2}{2}, \frac{4}{2}\right)=(0,1,2)

\)

Determine the Normal Vector to the Plane:

The line segment connecting the original point and its image is perpendicular to the plane. Therefore, the vector \(\overrightarrow{P_1 P_2}\) serves as the normal vector to the plane. The components of this vector are found by subtracting the coordinates of \(P_1\) from \(P_2\) :

\(

\vec{n}=\overrightarrow{P_1 P_2}=-2 \hat{i}-2 \hat{j}-2 \hat{k} \quad (-1-1,0-2,1-3)=(-2,-2,-2)

\)

Hence, the equation of the plane is \(-2(x-0)-2(y-1)-2(z-2)=0\) or \(x+y+z=3\)

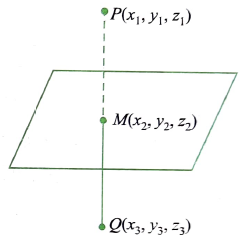

Equation of a Plane Passing through Three Given Points

Cartesian form

Let the plane be passing through points \(A\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), B\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\) and \(C\left(x_3, y_3, z_3\right)\).

Let \(P(x, y, z)\) be any point on the plane.

Then vectors \(\overrightarrow{P A}, \overrightarrow{B A}\) and \(\overrightarrow{C A}\) are coplanar.

\(\left[\begin{array}{lll}\overrightarrow{P A} & \overrightarrow{B A} & \overrightarrow{C A}\end{array}\right]=0\)

\(\left|\begin{array}{lll}x-x_1 & y-y_1 & z-z_1 \\ x_2-x_1 & y_2-y_1 & z_2-z_1 \\ x_3-x_1 & y_3-y_1 & z_3-z_1\end{array}\right|=0\), which is the required equation of the plane

Vector form

Vector form of the equation of the plane passing through three points \(A, B\) and \(C\) having position vectors \(\vec{a}, \vec{b}\) and \(\vec{c}\), respectively.

Let \(\vec{r}\) be the position vector of any point \(P\) in the plane.

Hence, vectors \(\overrightarrow{A P}=\vec{r}-\vec{a} \overrightarrow{A B}=\vec{b}-\vec{a}\) and \(\overrightarrow{A C}=\vec{c}-\vec{a}\) are coplanar, i.e.,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& (\vec{r}-\vec{a}) \cdot\{(\vec{b}-\vec{a}) \times(\vec{c}-\vec{a})\}=0 \\

\text { or } & (\vec{r}-\vec{a}) \cdot(\vec{b} \times \vec{c}-\vec{b} \times \vec{a}-\vec{a} \times \vec{c}+\vec{a} \times \vec{a})=0 \\

\text { or } & (\vec{r}-\vec{a}) \cdot(\vec{b} \times \vec{c}+\vec{a} \times \vec{b}+\vec{c} \times \vec{a})=0 \\

\text { or } & \vec{r} \cdot(\vec{b} \times \vec{c}+\vec{a} \times \vec{b}+\vec{c} \times \vec{a})=\vec{a} \cdot(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})+\vec{a} \cdot(\vec{a} \times \vec{b})+\vec{a} \cdot(\vec{c} \times \vec{a}) \\

\text { or } & {[\vec{r~} \vec{b~} \vec{c}]+[\vec{r~} \vec{a~} \vec{b}]+[\vec{r~} \vec{c~} \vec{a}]=[\vec{a~} \vec{b~} \vec{c}]}

\end{array}

\)

which is the required equation of the plane.

Note:

- If \(p\) is the length of perpendicular from the origin on this plane, then \(p=[\vec{a~} \vec{b~} \vec{c}] / n\), where \(n=|\vec{a} \times \vec{b}+\vec{b} \times \vec{c}+\vec{c} \times \vec{a}|\).

- Four point \(\vec{a}, \vec{b}, \vec{c}\) and \(\vec{d}\) are coplanar if \(\vec{d}\) lies on the plane containing \(\vec{a}, \vec{b}\) and \(\vec{c}\), i.e.,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \vec{d} \cdot[\vec{a} \times \vec{b}+\vec{b} \times \vec{c}+\vec{c} \times \vec{a}]=\left[\begin{array}{lll}

\vec{a} & \vec{b} & \vec{c}

\end{array}\right] \\

& {[\vec{d~} \vec{a~} \vec{b}]+[\vec{d~} \vec{b~} \vec{c}]+[\vec{d~} \vec{c~} \vec{a}]=\left[\begin{array}{lll}

\vec{a} & \vec{b} & \vec{c}

\end{array}\right]}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 30: Find the equation of the plane passing through \(A(2,2,-1), B(3,4,2)\) and \(C(7,0,6)\) Also find a unit vector perpendicular to this plane.

Solution: Here \(\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right) \equiv(2,2,-1),\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right) \equiv(3,4,2)\) and \(\left(x_3, y_3, z_3\right) \equiv(7,0,6)\)

Then the equation of the plane is

\(

\left|\begin{array}{lll}

x-x_1 & y-y_1 & z-z_1 \\

x_2-x_1 & y_2-y_1 & z_2-z_1 \\

x_3-x_1 & y_3-y_1 & z_3-z_1

\end{array}\right|=0 \text { or }\left|\begin{array}{lllr}

x-2 & y-2 & z -(-1) \\

3-2 & 4-2 & 2-(-1) \\

7-2 & 0-2 & 6-(-1)

\end{array}\right|=0

\)

\(

5 x+2 y-3 z=17

\)

A normal vector to this plane is \(\vec{d}=5 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}-3 \hat{k} \dots(i) \)

Therefore, a unit vector normal to (i) is given by

\(

\hat{n}=\frac{\vec{d}}{|\vec{d}|}=\frac{5 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}-3 \hat{k}}{\sqrt{25+4+9}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{38}}(5 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}-3 \hat{k})

\)

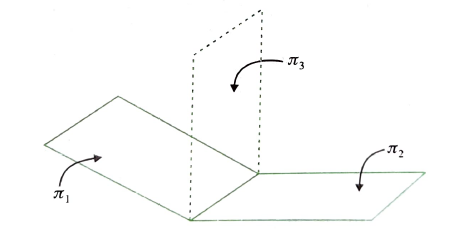

Example 31: Show that the line of intersection of the planes \(\vec{r} \cdot(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k})=0\) and \(\vec{r} \cdot(3 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+\hat{k}) =0\) is equally inclined to \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{k}\). Also find the angle it makes with \(\hat{j}\).

Solution: The line of intersection of the two planes will be perpendicular to the normals to the planes. Hence, it is parallel to the vector \((\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k}) \times(3 \hat{i}+2 \hat{j}+\hat{k})=(-4 \hat{i}+8 \hat{j}-4 \hat{k})\). Now,

\(

(-4 \hat{i}+8 \hat{j}-4 \hat{k}) \cdot \hat{i}=-4 \text { and }(-4 \hat{i}+8 \hat{j}-4 \hat{k}) \cdot \hat{k}=-4

\)

Hence, the line is equally inclined to \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{k}\). Also,

\(

\frac{(-4 \hat{i}+8 \hat{j}-4 \hat{k})}{\sqrt{16+64+16}} \cdot \hat{j}=\frac{8}{\sqrt{96}}=\sqrt{\frac{2}{3}}

\)

If \(\theta\) is the required angle, then \(\cos \theta=\sqrt{\frac{2}{3}}\) or \(\theta=\cos ^{-1} \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}}\).

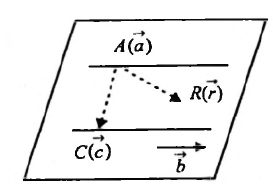

Equation of the Plane that Passes through Point A with Position Vector \(\vec{a}\) and is Parallel to Given Vectors \(\vec{b}\) and \(\vec{c}\)

Vector form

Let \(\vec{r}\) be the position vector of any point \(P\) in the plane. Then

\(

\overrightarrow{A P}=\overrightarrow{O P}-\overrightarrow{O A}=\vec{r}-\vec{a}

\)

Since vectors \(\vec{r}-\vec{a}, \vec{b}\) and \(\vec{c}\) are coplanar, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (\vec{r}-\vec{a}) \cdot(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})=0 \\

& \vec{r} \cdot(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})=\vec{a} \cdot(\vec{b} \times \vec{c}) \text { or }[\vec{r} \vec{b} \vec{c}]=[\vec{a} \vec{b} \vec{c}]

\end{aligned}

\)

which is the required equation of the plane.

Cartesian form

From \((\vec{r}-\vec{a}) \cdot(\vec{b} \times \vec{c})=0\), we have \([\vec{r}-\vec{a} \vec{b} \vec{c}]\)

\(\Rightarrow \quad\left|\begin{array}{ccc}x-x_1 & y-y_1 & z-z_1 \\ x_2 & y_2 & z_2 \\ x_3 & y_3 & z_3\end{array}\right|=0\), which is the required equation of the plane,

where \(\vec{b}=x_2 \hat{i}+y_2 \hat{j}+z_2 \hat{k}\) and \(\vec{c}=x_3 \hat{i}+y_3 \hat{j}+z_3 \hat{k}\).

Example 32: Find the vector equation of the following planes in cartesian form:

\(

\vec{r}=\hat{i}-\hat{j}+\lambda(\hat{i}+\hat{j}+\hat{k})+\mu(\hat{i}-2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k})

\)

Solution: The equation of the plane is \(\vec{r}=\hat{i}-\hat{j}+\lambda(\hat{i}+\hat{j}+\hat{k})+\mu(\hat{i}-2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k})\).

Let \(\vec{r}=x \hat{i}+y \hat{j}+z \hat{k}\)

Hence, the equation is \((x \hat{i}+y \hat{j}+z \hat{k})-(\hat{i}-\hat{j})=\lambda(\hat{i}+\hat{j}+\hat{k})+\mu(\hat{i}-2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k})\)

Thus, vectors \((x \hat{i}+y \hat{j}+z \hat{k})-(\hat{i}-\hat{j}), \hat{i}+\hat{j}+\hat{k}, \hat{i}-2 \hat{j}+3 \hat{k}\) are coplanar (Coplanar means to exist on the same plane).

Therefore, the equation of the plane is \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}x-1 & y-(-1) & z-0 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -2 & 3\end{array}\right|=0\) or \(5 x-2 y-3 z-7=0\)

Equation of a Plane Passing through a Given Point and Line

Let the plane pass through a given point \(A(\vec{a})\) and line \(\vec{r}=\vec{b}+\lambda \vec{c}\).

For any position of point \(R(\vec{r})\) on the plane, vectors \(\overrightarrow{A B}, \overrightarrow{R A}\) and \(\vec{c}\) are coplanar. Then \(\left[\begin{array}{lll}\vec{r}-\vec{a} & \vec{b}-\vec{a} & \vec{c}\end{array}\right]=0\), which is required equation of the plane.

Example 33: Prove that the plane \(\vec{r} \cdot(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}-\hat{k})=3\) contains the line \(\vec{r}=\hat{i}+\hat{j}+\lambda(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+4 \hat{k})\).

Solution: To show that \(\vec{r}=\hat{i}+\hat{j}+\lambda(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+4 \hat{k}) \dots(i)\)

lies in the plane \(\vec{r} \cdot(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}-\hat{k})=3 \dots(ii)\)

we must show that each point of (i) lies in (ii). In other words, we must show that \(\vec{r}\) in (i) satisfies (ii) for every value of \(\lambda\). We have

\(

\begin{aligned}

{[\hat{i}} & +\hat{j}+\lambda(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+4 \hat{k})] \cdot(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}-\hat{k}) \\

& =(\hat{i}+\hat{j}) \cdot(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}-\hat{k})+\lambda(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+4 \hat{k}) \cdot(\hat{i}+2 \hat{j}-\hat{k}) \\

& =(1)(1)+(1)(2)+\lambda[(2)(1)+(1)(2)+4(-1)]=3+\lambda(0)=3

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, line (i) lies in plane (ii).

Example 34: Find the equation of the plane which is parallel to the lines \(\vec{r}=\hat{i}+\hat{j}+\lambda(2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+4 \hat{k})\) and \(\frac{x+1}{-3}=\frac{y-3}{2}=\frac{z+2}{1}\) and is passing through the point \((0,1,-1)\).

Solution: The plane is parallel to the given lines, which are directed along vectors \(\vec{a}=2 \hat{i}+\hat{j}+4 \hat{k}\) and \(\vec{b}=-3 \hat{i}+\hat{2 j}+1 \hat{k}\).

Then the plane is normal to vector \(\vec{a} \times \vec{b} \equiv\left|\begin{array}{ccc}\hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\ 2 & 1 & 4 \\ -3 & 2 & 1\end{array}\right|=-7 \hat{i}-14 \hat{j}+7 \hat{k}\)

Also, the plane passes through the point \((0,1,-1)\).

Therefore, the equation of the plane is \(-7(x-0)-14(y-1)+7(z+1)=0\) or \(7 x+14 y-7 z=21\)