10.8 Entrance Corner (Coordinate geometry)

Summary

- Slope \((m)\) of a non-vertical line passing through the points \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and \(\left(x_2, y_2\right)\) is given by \(m=\frac{y_2-y_1}{x_2-x_1}=\frac{y_1-y_2}{x_1-x_2}, \quad x_1 \neq x_2\).

- If a line makes an angle \(\alpha\) with the positive direction of \(x\)-axis, then the slope of the line is given by \(m=\tan \alpha, \alpha \neq 90^{\circ}\).

- Slope of horizontal line is zero and slope of vertical line is undefined.

- An acute angle (say \(\theta\) ) between lines \(\mathrm{L}_1\) and \(\mathrm{L}_2\) with slopes \(m_1\) and \(m_2\) is given by \(\tan \theta=\left|\frac{m_2-m_1}{1+m_1 m_2}\right|, 1+m_1 m_2 \neq 0\).

- Two lines are parallel if and only if their slopes are equal.

- Two lines are perpendicular if and only if product of their slopes is -1 .

- Three points \(A, B\) and \(C\) are collinear, if and only if slope of \(A B=\) slope of \(B C\).

- Equation of the horizontal line having distance \(a\) from the \(x\)-axis is either \(y=a\) or \(y=-a\).

- Equation of the vertical line having distance \(b\) from the \(y\)-axis is either \(x=b\) or \(x=-b\).

- The point \((x, y)\) lies on the line with slope \(m\) and through the fixed point \(\left(x_0, y_0\right)\), if and only if its coordinates satisfy the equation \(y-y_0=m\left(x-x_0\right)\).

- Equation of the line passing through the points \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and \(\left(x_2, y_2\right)\) is given by

\(

y-y_1=\frac{y_2-y_1}{x_2-x_1}\left(x-x_1\right) .

\) - The point \((x, y)\) on the line with slope \(m\) and \(y\)-intercept \(c\) lies on the line if and only if \(y=m x+c\).

- If a line with slope \(m\) makes \(x\)-intercept \(d\). Then equation of the line is \(y=m(x-d)\).

- Equation of a line making intercepts \(a\) and \(b\) on the \(x\)-and \(y\)-axis, respectively, is \(\frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}=1\).

- The equation of the line having normal distance from origin \(p\) and angle between normal and the positive \(x\)-axis \(\omega\) is given by \(x \cos \omega+y \sin \omega=p\).

- Any equation of the form \(\mathrm{Ax}+\mathrm{B} y+\mathrm{C}=0\), with \(\mathrm{A}\) and \(\mathrm{B}\) are not zero, simultaneously, is called the general linear equation or general equation of a line.

- The perpendicular distance \((d)\) of a line \(\mathrm{A} x+\mathrm{B} y+\mathrm{C}=0\) from a point \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) is given by \(d=\frac{\left|\mathrm{A} x_1+\mathrm{B} y_1+\mathrm{C}\right|}{\sqrt{\mathrm{A}^2+\mathrm{B}^2}}\).

- Distance between the parallel lines \(\mathrm{A} x+\mathrm{B} y+\mathrm{C}_1=0\) and \(\mathrm{A} x+\mathrm{B} y+\mathrm{C}_2=0\), is given by \(d=\frac{\left|\mathrm{C}_1-\mathrm{C}_2\right|}{\sqrt{\mathrm{A}^2+\mathrm{B}^2}}\).

COORDINATE GEOMETRY

The coordination of algebra and geometry is called coordinate geometry. Historically, coordinates were introduced to help geometry. In coordinate geometry, all the properties of geometrical figures are studied with the help of algebraic equations. Students should note that the object of coordinate geometry is to use some known facts about a curve in order to obtain its equation and then deduce other properties of the curve from the equation so obtained. For this purpose, we require a coordinate system. There are various types of coordinate systems present in two dimensions e.g., rectangular, oblique, polar, triangular system, etc. Here, we will only discuss rectangular coordinate system in detail.

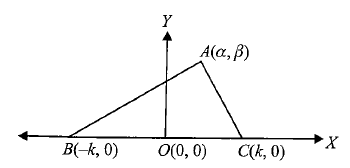

Example 1: In \(\triangle A B C\), prove that \(A B^2+A C^2\). \(=2\left(A O^2+B O^2\right)\), where \(O\) is the middle point of \(B C\).

Solution:

We take \(O[latex] as the origin and [latex]O C\) and \(O Y\) as the \(x\)-and \(y\)-axes, respectively.

Let \(\quad B C=2 k\), then \(B \equiv(-k, 0), C \equiv(k, 0)\).

Let \(\quad A \equiv(\alpha, \beta)\)

Now L.H.S.

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =A B^2+A C^2 \\

& =(\alpha+k)^2+(\beta-0)^2+(\alpha-k)^2+(\beta-0)^2 \\

& =\alpha^2+k^2+2 \alpha k+\beta^2+\alpha^2+k^2-2 \alpha k+\beta^2 \\

& =2 \alpha^2+2 \beta^2+2 k^2 \\

& =2\left(\alpha^2+\beta^2+k^2\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

and R.H.S

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =2\left(A O^2+B O^2\right) \\

& =2\left[(\alpha-0)^2+(\beta-0)^2+(-k-0)^2+(0-0)^2\right] \\

& =2\left(\alpha^2+\beta^2+k^2\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

\(\therefore \quad\) L.H.S. \(=\) R.H.S.

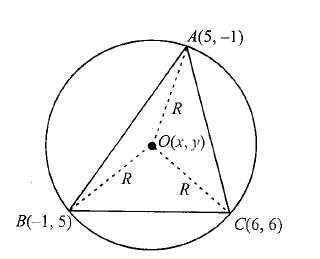

Example 2: Find the coordinates of the circumcentre of the triangle whose vertices are \(A(5,-1), B(-1,5)\), and \(C(6,6)\). Find its radius also.

Solution: The circumcenter of a triangle is the intersection point of the triangle’s three perpendicular bisectors, which is also the center of the triangle’s circumcircle. This point is equidistant from all three vertices of the triangle, and its location within, on, or outside the triangle depends on whether the triangle is acute, right, or obtuse, respectively.

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Let circumcentre be } O(x, y) \text {, then }\\

&\begin{aligned}

(O A)^2 & =(O B)^2=(O C)^2=(\text { radius })^2=R^2 \dots(i) \\

\Rightarrow(x-5)^2+(y+1)^2 & =(x+1)^2+(y-5)^2 \\

& =(x-6)^2+(y-6)^2

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Taking first two relations, we get

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (x-5)^2+(y+1)^2=(x+1)^2+(y-5)^2 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & x=y \dots(ii)

\end{aligned}

\)

Taking last two relations, we get

\(

\begin{aligned}

(x+1)^2+(y-5)^2 & =(x-6)^2+(y-6)^2 \\

\Rightarrow \quad(x+1)^2+(x-5)^2 & =(x-6)^2+(x-6)^2 \text { [from (ii)] }\\

\Rightarrow \quad 2 x^2-8 x+26 & =2 x^2-24 x+72 \\

x & =23 / 8

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\text { Circumcentre } & =(23 / 8,23 / 8) \\

R^2 & =(x-5)^2+(y+1)^2=(O A)^2 \\

& =[(23 / 8)-5]^2+[(23 / 8)+1]^2 \\

& =(-17)^2 /(64)+(31)^2 /(64) \\

& =1250 / 64 \\

\text { Radius } & =25 \sqrt{2} / 8 \text { units }

\end{aligned}

\)

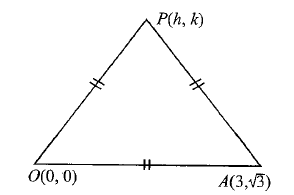

Example 3: Two points \(O(0,0)\) and \(A(3, \sqrt{3})\) with another point \(P\) form an equilateral triangle. Find the coordinates of \(P\).

Solution: Let the coordinates of \(P\) be \((h, k)\).

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & O A=O P=A P \text { or } O A^2=O P^2=A P^2 \\

\therefore & O A^2=O P^2 \\

\Rightarrow & 12=h^2+k^2 \dots(i) \\

\text { and } & O P^2=A P^2 \\

\Rightarrow & h^2+k^2=(h-3)^2+(k-\sqrt{3})^2 \\

\Rightarrow & 3 h+\sqrt{3} k=6 \text { or } h=2-k / \sqrt{3} \dots(ii)

\end{array}

\)

Using Eq. (ii) in Eq. (i), we get

\(

(2-k / \sqrt{3})^2+k^2=12 \text { or } k^2-\sqrt{3} k-6=0

\)

or \((k-2 \sqrt{3})(k+\sqrt{3})=0\)

\(

\therefore \quad k=2 \sqrt{3} \text { or }-\sqrt{3}

\)

From Eq. (ii), we get that

when

\(

\begin{aligned}

& k=2 \sqrt{3}, h=0 \\

& k=-\sqrt{3}, h=3

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the coordinates of \(P\) are

\(

(0,2 \sqrt{3}) \text { or }(3,-\sqrt{3})

\)

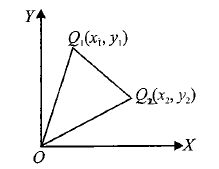

Example 4: If \(O\) is the origin and if coordinates of any two points \(Q_1\) and \(Q_2\) are \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and \(\left(x_2, y_2\right)\), respectively, prove that \(O Q_1 \cdot O Q_2 \cos \angle Q_1 O Q_2=x_1 x_2+y_1 y_2\).

Solution:

In \(\Delta Q_2 O Q_1\), \(Q_1 Q_2^2=O Q_1^2+O Q_2^2-2 O Q_1 O Q_2 \cos \angle Q_1 O Q_2\)

\(

\Rightarrow\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2=\left(x_1^2+y_1^2\right)+\left(x_2^2+y_2^2\right)-2 O Q_1 O Q_2 \cos \angle Q_1 O Q_2 \text { (using cosine Rule) }

\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad x_1 x_2+y_1 y_2=O Q_1 O Q_2 \cos Q_1 O Q_2

\)

Example 5: Let \(A=(3,4)\) and \(B\) is a variable point on the lines \(|x|=6\). If \(A B \leq 4\), then the number of position of \(B\) with integral coordinates is _____.

Solution: \(B=( \pm 6, y)\). So, \(A B \leq 4\)

\(

\begin{array}{rlrl}

\Rightarrow & (3 \mp 6)^2+(y-4)^2 & \leq 16 \\

\therefore & 9+(y-4)^2 & \leq 16, \\

& \Rightarrow & \left(\because 81+(y-4)^2\right. & \leq 16 \text { is absurd }) \\

\Rightarrow & y^2-8 y+9 & \leq 0 \\

4-\sqrt{7} & \leq y \leq 4+\sqrt{7}

\end{array}

\)

But \(y\) is an integer.

\(

\Rightarrow \quad y=2,3,4,5,6

\)

AREA OF A TRIANGLE

The area of a triangle, whose vertices are \(\left(x_1, y_1\right),\left(x_2, y_2\right)\), and \(\left(x_3, y_3\right)\) is

\(

\frac{1}{2}\left|x_1\left(y_2-y_3\right)+x_2\left(y_3-y_1\right)+x_3\left(y_1-y_2\right)\right|

\)

Proof:

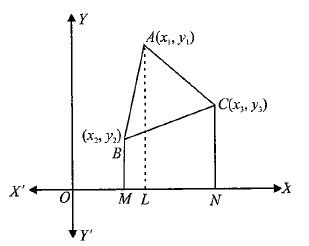

Let \(A B C\) be a triangle whose vertices are \(A\left(x_1, y_1\right), B\left(x_2, y_2\right)\), and \(C\left(x_3, y_3\right)\). Draw \(A L, B M\), and \(C N\) as perpendiculars from \(A, B\), and \(C\) on the \(x\)-axis. Clearly, \(A B M L, A L N C\) and \(B M N C\) are all trapeziums.

We have, Area of \(\triangle A B C=\) Area of trapezium \(A B M L+\) Area of trapezium \(A L N C\) – Area of trapezium \(B M N C\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\Rightarrow & \text { Area of } \triangle A B C=\frac{1}{2}(B M+A L)(M L)+\frac{1}{2}(A L+C N)(L N) \\

& -\frac{1}{2}(B M+C N)(M N)

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{array}{r}

=\frac{1}{2}\left(y_2+y_1\right)\left(x_1-x_2\right)+\frac{1}{2}\left(y_1+y_3\right)\left(x_3-x_1\right) \\

-\frac{1}{2}\left(y_2+y_3\right)\left(x_3-x_2\right) \\

=\frac{1}{2}\left[x_1\left(y_2-y_3\right)+x_2\left(y_3-y_1\right)+x_3\left(y_1-y_2\right)\right]

\end{array}

\)

\(

=\frac{1}{2}\left|\begin{array}{lll}

x_1 & y_1 & 1 \\

x_2 & y_2 & 1 \\

x_3 & y_3 & 1

\end{array}\right|

\)

Area of Polygon

A polygon is a flat, two-dimensional shape with straight sides that form a closed figure. It cannot have curved sides or gaps. Polygons are defined by their number of sides, which can be any number greater than or equal to three, such as a triangle ( 3 sides), square ( 4 sides), pentagon (5 sides), or hexagon (6 sides).

The area of polygon whose vertices are \(\left(x_1, y_1\right),\left(x_2, y_2\right)\), \(\left(x_3, y_3\right), \ldots,\left(x_n, y_n\right)\) is

\(

=\frac{1}{2}\left|\left\{\left(x_1 y_2-x_2 y_1\right)+\left(x_2 y_3-x_3 y_2\right)+\cdots+\left(x_n y_1-x_1 y_n\right)\right\}\right|

\)

Example 6: Find the area of a triangle whose vertices are \(A(3,2), B(11,8)\), and \(C(8,12)\).

Solution: Let \(A=\left(x_1, y_1\right)=(3,2), B\left(x_2, y_2\right)=(11,8)\), and \(C= \left(x_3, \mathrm{y}_3\right)=(8,12)\).

Then, area of \(\triangle A B C\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =\frac{1}{2}\left|\left\{x_1\left(y_2-y_3\right)+x_2\left(y_3-y_1\right)+x_3\left(y_1-y_2\right)\right\}\right| \\

& =\frac{1}{2}|\{3(8-12)+11(12-2)+8(2-8)\}| \\

& =\frac{1}{2}|\{-12+110-48\}| \\

& =25 \text { sq. units }

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 7: Find the area of the quadrilateral \(A B C D\) whose vertices are respectively \(A(1,1), B(7,-3), C(12,2)\), and \(D(7,21)\).

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Here, given points are in cyclic order, then }\\

&\text { Area }=\frac{1}{2}\left\|\begin{array}{cc}

1 & 1 \\

7 & -3 \\

12 & 2 \\

7 & 21 \\

1 & 1

\end{array}\right\|

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =\frac{1}{2}|(-3-7)+(14+36)+(252-14)+(7-21)| \\

& =132 \text { sq. units }

\end{aligned}

\)

Note:

- Area of a triangle can also be found by easy method, i.e., Stair method.

\(

\begin{aligned}

\Delta & =\frac{1}{2}\left|\begin{array}{ll}

x_1 & y_1 \\

x_2 & y_2 \\

x_3 & y_3 \\

x_1 & y_1

\end{array}\right| \\

& =\frac{1}{2}\left|\left\{\left(x_1 y_2+x_2 y_3+x_3 y_1\right)-\left(y_1 x_2+y_2 x_3+y_3 x_1\right)\right\}\right|

\end{aligned}

\) - If three points \(A, B\), and \(C\) are collinear, then area of triangle \(A B C\) is zero.

Example 8: For what value of \(k\) are the points \((k, 2-2 k),(-k+1,2 k)\) and \((-4-k, 6-2 k)\) are collinear?

Solution: Let three given points be \(A=\left(x_1, y_1\right)=(k, 2-2 k), B=\left(x_2, y_2\right) =(-k+1,2 k)\), and \(C=\left(x_3, y_3\right)=(-4-k, 6-2 k)\).

If the given points are collinear, then \(\Delta=0\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\Rightarrow & x_1\left(y_2-y_3\right)+x_2\left(y_3-y_1\right)+x_3\left(y_1-y_2\right)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & k(2 k-6+2 k)+(-k+1)(6-2 k-2+2 k) \\

& +(-4-k)(2-2 k-2 k)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & k(4 k-6)-4(k-1)+(4+k)(4 k-2)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 4 k^2-6 k-4 k+4+4 k^2+14 k-8=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 8 k^2+4 k-4=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 2 k^2+k-1=0 \\

\Rightarrow & (2 k-1)(k+1)=0 \\

\Rightarrow & k=1 / 2 \text { or }-1

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the given points are collinear for \(k=1 / 2\) or -1.

Example 9: If the vertices of a triangle have rational coordinates, then prove that the triangle cannot be equilateral.

Solution: Let \(A\left(x_1, y_1\right), B\left(x_2, y_2\right)\), and \(C\left(x_3, y_3\right)\) be the vertices of a triangle \(A B C\), where \(x_i, y_i, i=1,2,3\) are rational. Then, the area of \(\triangle A B C\) is given by

\(

\begin{aligned}

\Delta & =\frac{1}{2}\left[x_1\left(y_2-y_3\right)+x_2\left(y_3-y_1\right)+x_3\left(y_1-y_2\right)\right] \\

& =\text { a rational number } \quad\left[\because x_i, y_i \text { are rational }\right]

\end{aligned}

\)

If possible, let the triangle \(A B C\) be an equilateral triangle, then its area is given by

\(

\Delta=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}(\text { side })^2=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}(A B)^2 \quad(\because A B=B C=C A)

\)

\(=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4} \times (\) a rational number \() \quad[\because\) vertices are rational

\(\therefore A B^2\) is a rational]

\(=\) an irrational number

This is a contradication to the fact that the area is a rational number. Hence, the triangle cannot be equilateral.

Example 10: If the coordinates of two points \(A\) and \(B\) are \((3,4)\) and \((5,-2)\), respectively. Find the coordinates of any point \(P\) if \(P A=P B\) and area of \(\triangle P A B=10\) sq. units.

Solution: Let the coordinates of \(P\) be \((x, y)\). Then, \(P A=P B\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad P A^2=P B^2 \\

& \Rightarrow(x-3)^2+(y-4)^2=(x-5)^2+(y+2)^2 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x-3 y-1=0 \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Now, area of } \triangle P A B=10 \text { sq. units }\\

&\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & \frac{1}{2}\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x & y & 1 \\

3 & 4 & 1 \\

5 & -2 & 1

\end{array}\right|= \pm 10 \\

\Rightarrow & 6 x+2 y-26= \pm 20 \\

\Rightarrow & 6 x+2 y-46=0 \\

\text { or } & 6 x+2 y-6=0 \\

\Rightarrow & 3 x+y-23=0 \text { or } 3 x+y-3=0 \dots(ii)

\end{array}

\end{aligned}

\)

Solving \(x-3 y-1=0\) and \(3 x+y-23=0\), we get \(x=7\),

\(

y=2

\)

Solving \(x-3 y-1=0\) and \(3 x+y-3=0\), we get \(x=1\),

\(

y=0

\)

Thus, the coordinates of \(P\) are \((7,2)\) or \((1,0)\).

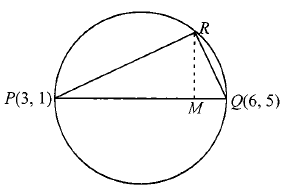

Example 11: Given that \(P(3,1), Q(6,5)\), and \(R(x, y)\) are three points such that the angle \(P R Q\) is a right angle and the area of \(\triangle R Q P=7\), then find the number of such points \(R\).

Solution: Obviously, \(R\) lies on the circle with \(P\) and \(Q\) as end points of diameter.

Distance between points \(P(3,1)\) and \(Q(6,5)\) is 5 units. Hence, radius is 2.5 units

Area of triangle \(P Q R=\frac{1}{2} R M \times P Q=7\) (given)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad R M=\frac{14}{5}=2.8

\)

Now the value of \(R M\) cannot be greater than the radius. Hence. no such triangle is possible.

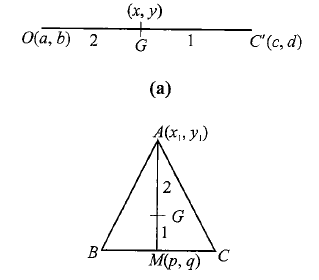

SECTION FORMULA

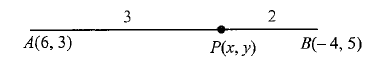

Formula for Internal Division

Coordinates of the point that divides the line segment joining the points \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and \(\left(x_2, y_2\right)\) internally in the ratio \(m: n\) are given by

\(

\begin{aligned}

&x=\frac{m x_2+n x_1}{m+n},\\

&y=\frac{m y_2+n y_1}{m+n}

\end{aligned}

\)

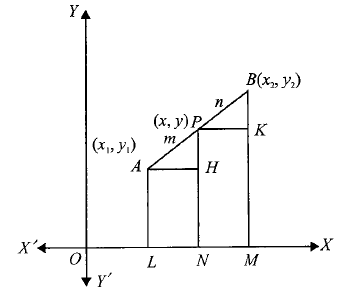

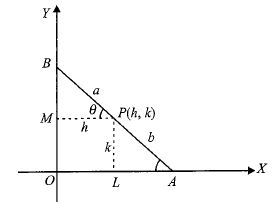

Proof:

From the figure, Clearly, \(\triangle A H P\) and \(\triangle P K B\) are similar.

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & \frac{A P}{B P}=\frac{A H}{P K}=\frac{P H}{B K} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{m}{n}=\frac{x-x_1}{x_2-x}=\frac{y-y_1}{y_2-y}

\end{array}

\)

Now, \(\frac{m}{n}=\frac{x-x_1}{x_2-x}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

m x_2-m x & =n x-n x_1 \\

x & =\frac{m x_2+n x_1}{m+n}

\end{aligned}

\)

Similarly

\(

\frac{m}{n}=\frac{y-y_1}{y_2-y}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{array}{rlrl}

\Rightarrow & & m y_2-m y & =n y-n y_1 \\

\Rightarrow & & y=\frac{m y_2+n y_1}{m+n}

\end{array}\\

&\text { Thus, the coordinates of } P \text { are }\left(\frac{m x_2+n x_1}{m+n}, \frac{m y_2+n y_1}{m+n}\right) \text {. }

\end{aligned}

\)

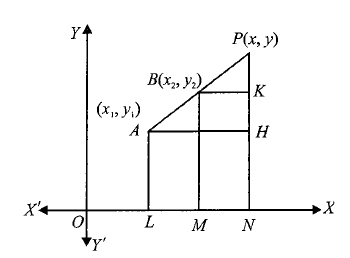

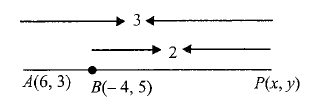

Formula for External Division

Coordinates of the point that divides the line segment joining the points \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and \(\left(x_2, y_2\right)\) externally in the ratio \(m: n\) are given by

\(

x=\frac{m x_2-n x_1}{m-n}, y=\frac{m y_2-n y_1}{m-n}

\)

Proof:

From the figure, Clearly, triangles \(P A H\) and \(P B K\) are similar. Therefore,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

& \frac{A P}{P B}=\frac{A H}{B K}=\frac{P H}{P K} \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{m}{n}=\frac{x-x_1}{x-x_2}=\frac{y-y_1}{y-y_2}

\end{array}

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{array}{rlrl}

& & \frac{m}{n}=\frac{x-x_1}{x-x_2} \\

& \Rightarrow & m x-m x_2 & =n x-n x_1 \\

& \Rightarrow & x & =\frac{m x_2-n x_1}{m-n}

\end{array}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{aligned}

& & \frac{m}{n} & =\frac{y-y_1}{y-y_2} \\

& \Rightarrow & m y-m y_2 & =n y-n y_1 \\

& \Rightarrow & y & =\frac{m y_2-n y_1}{m-n}

\end{aligned}\\

&\text { Thus, the coordinates of } P \text { are }\left(\frac{m x_2-n x_1}{m-n}, \frac{m y_2-n y_1}{m-n}\right) \text {. }

\end{aligned}

\)

Note:

- If the ratio, in which a given line segment is divided, is to be determined, then sometimes, for convenience (instead of taking the ratio \(m: n\) ), we take the ratio \(\lambda: 1\) and apply the formula for internal division \(\left(\frac{\lambda x_2+x_1}{\lambda+1}, \frac{\lambda y_2+y_1}{\lambda+1}\right)\). If the value of \(\lambda\) turns.out to be positive, it is an internal division, otherwise it is an external division.

- The midpoint of \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) and \(\left(x_2, y_2\right)\) is \(\left(\frac{x_1+x_2}{2}, \frac{y_1+y_2}{2}\right)\).

Example 12: The coordinates of the point which divides the line segments joining the points \((6,3)\) and \((-4,5)\) in the ratio \(3: 2\) (i) internally and (ii) externally.

Solution: (i) For internal division, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=\frac{3(-4)+2(6)}{3+2} \\

& y=\frac{3(5)+2(3)}{3+2} \\

& x=0 \text { and } y=21 / 5

\end{aligned}

\)

So the coordinates of \(P\) are \((0,21 / 5)\).

(ii) For external division, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=\frac{3(-4)-2(6)}{3-2} \\

& y=\frac{3(5)-2(3)}{3-2} \\

& x=-24 \text { and } y=9

\end{aligned}

\)

So the coordinates of \(P\) are \((-24,9)\).

Example 13: In what ratio does the \(x\)-axis divide the line segment joining the points \((2,-3)\) and \((5,6)\) ?

Solution: Let the required ratio be \(\lambda: 1\).

Then, the coordinates of the point of division are

\(

[(5 \lambda+2) /(\lambda-1),(6 \lambda-3) /(\lambda+1)]

\)

But, it is a point on \(x\)-axis on which \(y\)-coordinates of every point is zero.

\(

\begin{aligned}

\Rightarrow & & (6 \lambda-3) /(\lambda+1) & =0 \\

\Rightarrow & & \lambda & =\frac{1}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus, the required ratio is \((1 / 2): 1\) or \(1: 2\)

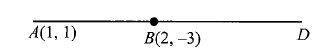

Example 14: Given that \(A(1,1)\) and \(B(2,-3)\) are two points and \(D\) is a point on \(A B\) produced such that \(A D=3 A B\). Find the coordinates of \(D\).

Solution: We have, \(A D=3 A B\). Therefore, \(B D=2 A B\).

Thus, \(D\) divides \(A B\) externally in the ratio \(A D: B D=3: 2\)

Hence, the coordinates of \(D\) are

\(

\left(\frac{3(2)-2(1)}{3-2}, \frac{3(-3)-2(1)}{3-2}\right)=(4,-11)

\)

Example 15: Determine the ratio in which the line \(3 x+y-9=0\) divides the segment joining the points \((1,3)\) and \((2,7)\).

Solution: Suppose the line \(3 x+y-9=0\) divides the line segment joining \(A(1,3)\) and \(B(2,7)\) in the ratio \(k: 1\) at point \(C\). Then, the coordinates of \(C\) are

\(

\left(\frac{2 k+1}{k+1}, \frac{7 k+3}{k+1}\right)

\)

But, \(\quad C\) lies on \(3 x+y-9=0\). Therefore,

\(

\begin{aligned}

3\left(\frac{2 k+1}{k+1}\right)+\frac{7 k+1}{k+1}-9 & =0 \\

\Rightarrow 6 k+3+7 k+3-9 k-9 & =0 \\

\Rightarrow \quad k & =\frac{3}{4}

\end{aligned}

\)

So, the required ratio is \(3: 4\) internally

Example 16: Prove that the points \((-2,-1),(1,0)\), \((4,3)\), and \((1,2)\) are the vertices of a parallelogram. Is it a rectangle?

Solution: Let the given points be \(A, B, C\), and \(D\), respectively. Then, the coordinates of the midpoint of \(A C\) are

\(

\left(\frac{-2+4}{2}, \frac{-1+3}{2}\right)=(1,1)

\)

Coordinates of the midpoint of \(B D\) are

\(

\left(\frac{1+1}{2}, \frac{0+2}{2}\right)=(1,1)

\)

Thus, \(A C\) and \(B D\) have the same midpoint.

Hence, \(A B C D\) is a parallelogram.

Now, we shall see whether \(A B C D\) is a rectangle or not.

We have

\(

\begin{aligned}

A C & =\sqrt{(4-(-2))^2+(3-(-1))^2} \\

& =2 \sqrt{13}

\end{aligned}

\)

and \(B D=\sqrt{(1-1)^2+(0-2)^2}=2\)

Clearly, \(A C \neq B D\). So, \(A B C D\) is not a rectangle.

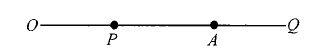

Example 17: If \(P\) divides \(O A\) internally in the ratio \(\lambda_1: \lambda_2\) and \(Q\) divides \(O A\) externally in the ratio \(\lambda_1: \lambda_2\), then prove that \(O A\) is the harmonic mean of \(O P\) and \(O Q\).

Solution:

We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1}{O P} & =\frac{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}{\lambda_1 O A} \\

\frac{1}{O P} & =\frac{\lambda_1-\lambda_2}{\lambda_1 O A} \\

+\frac{1}{O Q} & =\frac{2}{O A}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(\Rightarrow O P, O A\) and \(O Q\) are in H.P.

Note: If \(\mathrm{x}_1, \mathrm{x}_2, \mathrm{x}_3, \ldots, \mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{n}}\) are the individual items up to \(n\) terms, then, Harmonic Mean, \(\mathrm{HM}=\mathrm{n} /\left[\left(1 / \mathrm{x}_1\right)+\left(1 / \mathrm{x}_2\right)+\left(1 / \mathrm{x}_3\right)+\ldots+\left(1 / \mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{n}}\right)\right]\)

Example 18: Given that \(A_1, A_2, A_3, \ldots, A_n\) are \(n\) points in a plane whose coordinates are \(\left(x_1, y_1\right),\left(x_2, y_2\right), \ldots\left(x_n, y_n\right)\), respectively. \(A_1 A_2\) is bisected at the point \(P_1, P_1 A_3\) is divided in the ratio \(1: 2\) at \(P_2, P_2 A_4\) is divided in the ratio \(1: 3\) at \(P_3, P_3 A_5\) is divided in the ratio \(1: 4\) at \(P_4\), and so on until all \(n\) points are exhausted. Find the final point so obtained.

Solution: The coordinates of \(P_1\) (midpoint of \(A_1 A_2\) ) are

\(

\left(\frac{x_1+x_2}{2}, \frac{y_1+y_2}{2}\right)

\)

\(P_2\) divides \(P_1 A_3\) in \(1: 2\); therefore, coordinates of \(P_2\) are

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{aligned}

& \left(\frac{2\left(\frac{x_1+x_2}{2}\right)+x_3}{2+1}, \frac{2\left(\frac{y_1+y_2}{2}\right)+y_3}{2+1}\right) \\

& \text { i.e., }\left(\frac{x_1+x_2+x_3}{3}, \frac{y_1+y_2+y_3}{3}\right)

\end{aligned}\\

&\text { Now } P_3 \text { divides } P_1 A_4 \text { in } 1: 3 \text {, therefore, }\\

&\begin{aligned}

P_3 & =\left(\frac{3 \frac{\left(x_1+x_2+x_3\right)}{3}+x_4}{3+1}, \frac{3 \frac{\left(y_1+y_2+y_3\right)}{3}+y_4}{3+1}\right) \\

& =\left[\frac{1}{4}\left(x_1+x_2+x_3+x_4\right), \frac{1}{4}\left(y_1+y_2+y_3+y_4\right)\right]

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Proceeding in this manner, we can show that the coordinates of the final point are

\(

\left[\left(x_1+x_2+\cdots+x_n\right) / n,\left(y_1+y_2+\cdots+y_n\right) / n\right]

\)

COORDINATES OF THE CENTROID, INCENTRE, AND EX-CENTRES OF A TRIANGLE

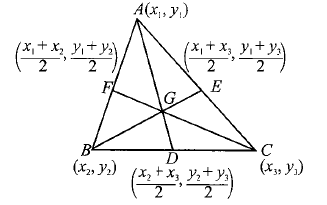

Centroid of a Triangle

The centroid of a triangle is the intersection point of its three medians, where a median connects a vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side. It represents the triangle’s center of gravity and is found in coordinate geometry by averaging the x and y coordinates of the triangle’s three vertices.

The point of concurrency of the medians of a triangle is called the centroid of the triangle. The coordinates of the centroid of the triangle with vertices as \(\left(x_1, y_1\right),\left(x_2, y_2\right)\), and \(\left(x_3, y_3\right)\) are

\(

\left(\frac{x_1+x_2+x_3}{3}, \frac{y_1+y_2+y_3}{3}\right)

\)

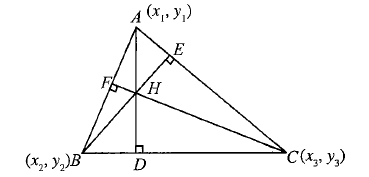

Proof: Let \(A\left(x_1, y_1\right), B\left(x_2, y_2\right)\), and \(C\left(x_3, y_3\right)\) be the vertices of \(\triangle A B C\) whose medians are \(A D, B E\), and \(C F\), respectively. So \(D, E\), and \(F\) are respectively the midpoint of \(B C, C A\), and \(A B\).

Coordinates of \(D\) are

\(

\left(\frac{x_2+x_3}{2}, \frac{y_2+y_3}{2}\right)

\)

Coordinates of a points \(G\) dividing \(A D\) in the ratio \(2: 1\) are

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(\frac{1\left(x_1\right)+2\left(\frac{x_2+x_3}{2}\right)}{1+2}, \frac{1\left(y_1\right)+2\left(\frac{y_2+y_3}{2}\right)}{1+2}\right) \\

& \quad=\left(\frac{x_1+x_2+x_3}{3}, \frac{y_1+y_2+y_3}{3}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

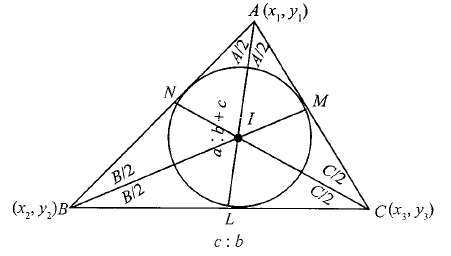

Incentre of a Triangle

The incenter of a triangle is the unique point where the three internal angle bisectors of the triangle intersect. It serves as the center of the triangle’s incircle, which is the largest circle that can fit inside the triangle and touches all three sides. The incenter is equidistant from all three sides of the triangle.

The point of concurrency of the internal bisectors of the angles of a triangle is called the incentre of the triangle. The coordinates of the incentre of a triangle with vertices as \(A\left(x_1, y_1\right), B\left(x_2, y_2\right)\) and \(C\left(x_3, y_3\right)\) are

\(

\left(\frac{a x_1+b x_2+c x_3}{a+b+c}, \frac{a y_1+b y_2+c y_3}{a+b+c}\right)

\)

where \(\mathrm{a}=B C, b=A C\) and \(C=A B\)

Proof: Let \(A\left(x_1, y_1\right), B\left(x_2, y_2\right), C\left(x_3, y_3\right)\) be the vertices of the triangle \(A B C\), and let \(a, b, c\) be the lengths of the sides \(B C, C A, A B\), respectively.

The point at which the bisectors of the angles of a triangle intersect is called the incentre of the triangle.

Let \(A L, B M\), and \(C N\) be respectively the internal bisectors of the angles \(A, B\) and \(C\).

As \(A L\) bisects \(\angle B A C\) internally, we have

\(

\frac{B L}{L C}=\frac{B A}{A C}=\frac{c}{b} \dots(i)

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\frac{L C}{B L} & =\frac{b}{c} \\

\frac{L C}{B L}+1 & =\frac{b}{c}+1 \\

\frac{L C+B L}{B L} & =\frac{b+c}{c} \\

\frac{B C}{B L} & =\frac{b+c}{c} \\

\frac{a}{B L} & =\frac{b+c}{c} \\

B L & =\frac{a c}{b+c} \dots(ii)

\end{aligned}

\)

Since \(B I\) is the bisector of \(\angle B\), so it divides \(A I L\) in the ratio \(A I: I L\)

\(

\therefore \quad \frac{A I}{I L}=\frac{A B}{B L}=\frac{c}{(a c) /(b+c)}=\frac{b+c}{a} \text { [Using (ii)] }

\)

\(

A I: I L=(b+c): a \dots(iii)

\)

From (i), \(L\) divides \(B C\) in the ratio \(c: b\)

\(\Rightarrow\) Coordinates of \(L\) are

\(

\left(\frac{b x_2+c x_3}{b+c}, \frac{b y_2+c y_3}{b+c}\right)

\)

From (iii), \(I\) divides \(A L\) in the ratio \((b+c): a\). So the coordinates of \(I\) are

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(\frac{a x_1+(b+c)\left(\frac{b x_2+c x_3}{b+c}\right)}{a+b+c}, \frac{a y_1+(b+c)\left(\frac{b y_2+c y_3}{b+c}\right)}{a+b+c}\right) \\

& \operatorname{or}\left(\frac{a x_1+b x_2+c x_3}{a+b+c}, \frac{a y_1+b y_2+c y_3}{a+b+c}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

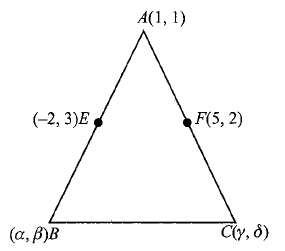

Example 19: If a vertex of a triangle is \((1,1)\), and the middle points of two sides passing through it are ( \(-2,3\) ) and \((5,2)\), then find the centroid and the incentre of the triangle.

Solution:

Let \(E\) and \(F\) be the midpoints of \(A B\) and \(A C\).

Let the coordinates of \(B\) and \(C\) be \((\alpha, \beta)\) and \((\gamma, \delta)\), respectively, then

\(

\begin{aligned}

-2 & =\frac{1+\alpha}{2}, 3=\frac{1+\beta}{2} \\

5 & =\frac{1+\gamma}{2}, 2=\frac{1+\delta}{2} \\

\therefore \quad & \alpha=-5, \beta=5, \gamma=9, \delta=3

\end{aligned}

\)

Therefore, coordinates of \(B\) and \(C\) are \((-5,5)\) and \((9,3)\), respectively.

Then, centroid is

\(

\left(\frac{1-5+9}{3}, \frac{1+5+3}{3}\right), \text { i.e., }\left(\frac{5}{3}, 3\right)

\)

and

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a=B C=\sqrt{(-5-9)^2+(5-3)^2}=10 \sqrt{2} \\

& b=C A=\sqrt{(9-1)^2+(3-1)^2}=2 \sqrt{17}

\end{aligned}

\)

and \(c=A B=\sqrt{(1+5)^2(1-5)^2}=2 \sqrt{13}\)

Then incentre is

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(\frac{10 \sqrt{2}(1)+2 \sqrt{17}(-5)+2 \sqrt{13}(9)}{10 \sqrt{2}+2 \sqrt{17}+2 \sqrt{13}}\right. \\

& \left.\frac{10 \sqrt{2}(1)+2 \sqrt{17}(5)+2 \sqrt{13}(3)}{10 \sqrt{2}+2 \sqrt{17}+2 \sqrt{13}}\right) \\

& \text { i.e., }\left(\frac{5 \sqrt{2}-5 \sqrt{17}+9 \sqrt{13}}{5 \sqrt{2}+\sqrt{17}+\sqrt{13}}, \frac{5 \sqrt{2}+5 \sqrt{17}+3 \sqrt{13}}{5 \sqrt{2}+\sqrt{17}+\sqrt{13}}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

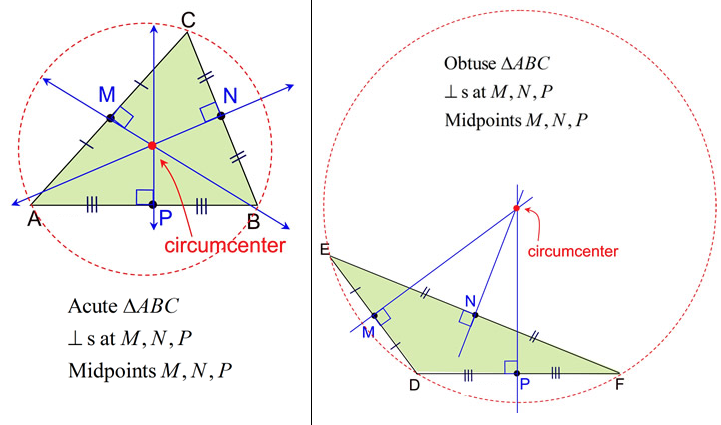

Circumcentre of a Triangle

The circumcenter of a triangle is the intersection point of the triangle’s three perpendicular bisectors, which is also the center of the triangle’s circumcircle. This point is equidistant from all three vertices of the triangle, and its location within, on, or outside the triangle depends on whether the triangle is acute, right, or obtuse, respectively.

Circumcentre \(P(x, y)\) is a point which is equidistant from the vertices of triangle \(A\left(x_1, y_1\right), B\left(x_2, y_2\right), C\left(x_3, y_3\right)\).

Hence, \(A P=B P=C P\), which gives two equations in \(x\) and \(y\), solving which we get circumcentre.

Also circumcentre is given by

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(\frac{x_1 \sin 2 A+x_2 \sin 2 B+x_3 \sin 2 C}{\sin 2 A+\sin 2 B+\sin 2 C},\right. \\

& \left.\quad \frac{y_1 \sin 2 A+y_2 \sin 2 B+y_3 \sin 2 C}{\sin 2 A+\sin 2 B+\sin 2 C}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Orthocentre

The orthocenter of a triangle is the point where all three altitudes of the triangle intersect. An altitude is a line segment from a vertex of a triangle perpendicular to the opposite side. In other words, it’s where the heights of the triangle meet.

The point of concurrency of the altitudes of a triangle is called the orthocentre of the triangle.

In Figure above point \(H\) is an orthocentre of \(\triangle A B C\), and it is given by

\(

\left(\frac{x_1 \tan A+x_2 \tan B+x_3 \tan C}{\tan A+\tan B+\tan C}, \frac{y_1 \tan A+y_2 \tan B+y_3 \tan C}{\tan A+\tan B+\tan C}\right)

\)

Note:

- Circumcentre O, Centroid G, and Orthocentre H of an acute \(\triangle A B C\) are collinear. \(G\) divides \(O H\) in the ratio \(1: 2\), i.e., \(O G: G H=1: 2\)

- In an isosceles triangle, centroid, orthocentre, incentre, and circumcentre lie on the same line. In an equilateral triangle, all these four points coincide.

Example 20: Find the orthocentre of the triangle whose vertices are \((0,0),(3,0)\), and \((0,4)\).

Solution: This is a right-angled (at origin) triangle, therefore orthocentre \(=(0,0)\).

Example 21: If the vertices \(P, Q, R\) of a triangle \(P Q R\) are rational points, which of the following points of the triangle \(P Q R\) is (are) not necessarily rational?

a. centroid

b. incentre

c. circumcentre

d. orthocentre

(A rational point is a point both of whose coordinates are rational numbers)

Solution: If \(A=\left(x_1, y_1\right), B=\left(x_2, y_2\right), C=\left(x_2, y_3\right)\), where \(x_1, y_1\) etc., are rational numbers, then \(\Sigma x_1, \Sigma y_1\) are also rational.

So, the coordinates of the centroid \(\left(\Sigma x_1 / 3, \Sigma y_1 / 3\right)\) will be rational.

As \(A B=c=\sqrt{\left(x_1-x_2\right)^2+\left(y_1-y_2\right)^2}\) may or may not be rational and it may be an irrational number of the form \(\sqrt{p}\). Hence, the coordinates of the incentre \(\left(\Sigma a x_1 / \Sigma a, \Sigma a y_1 / \Sigma a\right)\) may or may not be rational. If \((\alpha, \beta)\) is the circumcentre or orthocentre, \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are found by solving two linear equations in \(\alpha, \beta\) with rational coefficients. So \(\alpha, \beta\) must be rational numbers.

Example 22: If the circumcentre of an acute angled triangle lies at the origin and the centroid is the middle point of the line joining the points \(\left(a^2+1, a^2+1\right)\) and \((2 a\), \(-2 a\) ), then find the orthocentre.

Solution: We know from geometry that the circumcentre ( \(O\) ) centroid ( \(G\) ) and orthocentre ( \(H\) ) of a triangle lie on the line joining the circumcentre \((0,0)\) and the centroid \(\left((a+1)^2 / 2\right.\), \(\left.(a-1)^2 / 2\right)\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { Also } \quad \frac{\mathrm{HG}}{\mathrm{GO}}=\frac{2}{1} \Rightarrow H \text { has coordinate } \\

& \left(\frac{3(a+1)^2}{2}, \frac{3(a-1)^2}{2}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 23: If a vertex, the circumcentre, and the centroid of a triangle are \((0,0),(3,4)\), and \((6,8)\), respectively, then the triangle must be

a. a right-angled triangle

b. an equilateral triangle

c. an isosceles triangle

d. a right-angled isosceles triangle

Solution: Clearly, \((0,0),(3,4)\), and \((6,8)\) are collinear. So, the circumcentre \(M\) and the centroid \(G\) are on the median which is also the perpendicular bisector of the side. So, the \(\Delta\) must be isosceles.

Example 24: Orthocentre and circumcentre of a \(\triangle A B C\) are ( \(a, b\) ) and ( \(c, d\) ), respectively. If the coordinates of the vertex \(A\) are ( \(x_1, y_1\) ), then find the coordinates of the middle point of \(B C\).

Solution:

\(

x=\frac{a+2 c}{3} ; y=\frac{b+2 d}{3}

\)

Now,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=\frac{x_1+2 p}{3} ; y=\frac{y_1+2 q}{3} \\

& p=\frac{a+2 c-x_1}{2} ; q=\frac{b+2 d-y_1}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

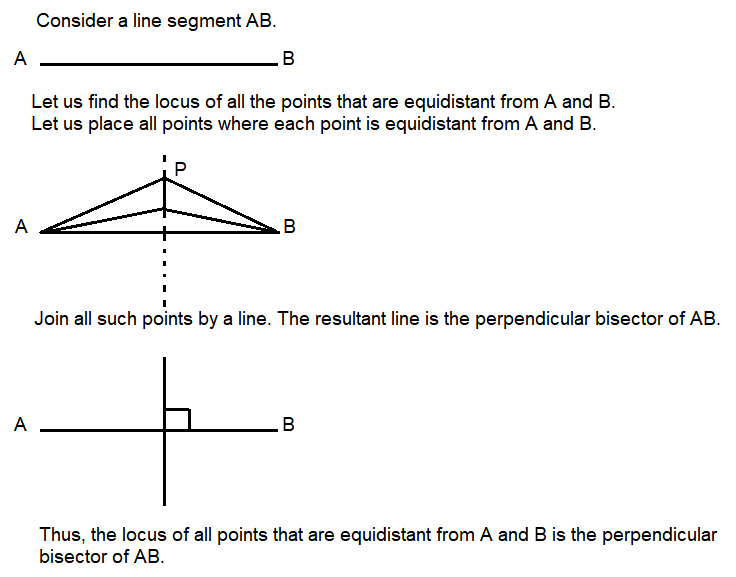

LOCUS AND EQUATION TO A LOCUS

Locus

“Locus” basically means a shape or a curve. We know that any shape or curve is formed by a set of points. So “Locus” is a set of points. In math, the locus is a set of points that satisfy a set of rules. The locus of points defines a shape in geometry. The locus of points is a curve or a line in two-dimensional geometry. For example, a circle is the locus of all the points which are equidistant from the centre. Similarly, the other shapes such as an ellipse, parabola, hyperbola, etc. are defined by the locus of the points.

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be two fixed points in the plane of the paper, and \(P\) be a variable point in the plane of the paper which moves in such a way that its distance from \(A\) and \(B\) is always same. Thus, the “locus” of \(P\) is the perpendicular bisector of \(A B\) when it moves under the condition that its distance from A and \(B\) is always equal.

Example 25: Find the locus of a point that is at a distance of 4 units from a point \((-3,2)\) in the \(x y\)-plane.

Solution: Let us assume that \(P(x, y)\) is a point on the locus.

Then by the given condition,

The distance between \((x, y)\) and \((-3,2)\) is 4.

\(

\sqrt{(x-(-3))^2+(y-2)^2}=4

\)

Squaring on both sides,

\(

\begin{aligned}

(x+3)^2+(y-2)^2 & =16 \\

x^2+6 x+9+y^2-4 y+4 & =16 \\

x^2+y^2+6 x-4 y-3 & =0

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus, the locus of the required points is, \(x^2+y^2+6 x-4 y-3=0\)

Equation to Locus of a Point

The equation to the locus of a point is the relation which is satisfied by the coordinates of every point on the locus of the point.

Steps to find locus of a points

- Step I: Assume the coordinates of the point say \((h, k)\) whose locus is to be found.

- Step II: Write the given condition in mathematical form involving \(h, k\).

- Step III: Eliminate the variable(s), if any.

- Step IV: Replace \(h\) by \(x\) and \(k\) by \(y\) in the result obtained in step III.

The equation so obtained is the locus of the point which moves under some stated condition(s).

Example 26: The sum of the squares of the distances of a moving point from two fixed points \((a, 0)\) and \((-a, 0)\) is equal to a constant quantity \(2 c^2\). Find the equation to its locus.

Solution: Let \(P(h, k)\) be any position of the moving point and let \(A(a, 0), B(-a, 0)\) be the given points.

Then, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

P A^2+P B^2 & =2 c^2 \text { (given) } \\

\Rightarrow(h-a)^2+(k-0)^2+(h+a)^2+(k-0)^2 & =2 c^2 \\

2 h^2+2 k^2+2 a^2 & =2 c^2 \\

\Rightarrow \quad h^2+k^2 & =c^2-a^2

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, equation to locus \((h, k)\) is \(x^2+y^2=c^2-a^2\).

Example 27: Find the locus of a point, so that the join of \((-5,1)\) and \((3,2)\) subtends a right angle at the moving point.

Solution: Let \(P(h, k)\) be a moving point and let \(A(-5,1)\) and \(B(3,2)\) be given points.

By the given condition, we have

\(

\angle A P B=90^{\circ}

\)

\(\Rightarrow \triangle A P B\) is a right-angled triangle

\(

\begin{array}{lr}

\Rightarrow & A B^2=A P^2+P B^2 \\

\Rightarrow & (3+5)^2+(2-1)^2=(h+5)^2+(k-1)^2+(h-3)^2 \\

& +(k-2)^2 \\

\Rightarrow & 65=2\left(h^2+k^2+2 h-3 k\right)+39 \\

\Rightarrow & h^2+k^2+2 h-3 k-13=0

\end{array}

\)

Hence, locus of \((h, k)\) is \(x^2+y^2+2 x-3 y-13=0\).

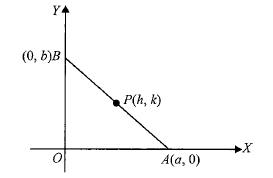

Example 28: A rod of length \(l\) slides with its ends on two perpendicular lines. Find the locus of its midpoint.

Solution: Let the two perpendicular lines be the coordinates axes.

Let \(A B\) be a rod of length \(l\).

Let the coordinates of \(A\) and \(B\) be \((a, 0)\) and \((0, b)\), respectively.

As the rod slides, the values of \(a\) and \(b\) change.

So \(a\) and \(b\) are two variables.

Let \(P(h, k)\) be the midpoint of the \(\operatorname{rod} A B\) in one of the infinite positions it attains.

Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& h=\frac{a+0}{2} \text { and } k=\frac{0+b}{2} \\

& h=\frac{a}{2} \text { and } k=\frac{b}{2} \dots(i)

\end{aligned}

\)

From \(\triangle O A B\), we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& & A B^2 & =O A^2+O B^2 \\

\Rightarrow & & a^2+b^2 & =l^2 \\

\Rightarrow & & (2 h)^2+(2 k)^2 & =l^2 \text { [Using (i)] } \\

\Rightarrow & & 4 h^2+4 k^2 & =l^2

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the locus of \((h, k)\) is \(4 x^2+4 y^2=l^2\)

Example 29: \(AB\) is a variable line sliding between the coordinate axes in such a way that \(A\) lies on \(x\)-axis and \(B\) lies on \(y\)-axis. If \(P\) is a variable point on \(A B\) such that \(P A=b, P B=a\), and \(A B=a+b\), find the equation of the locus of \(P\).

Solution: Let \(P(h, k)\), be a variable point on \(A B\) such that \(\angle O A B=\theta\).

Here \(\theta\) is a variable.

From triangles \(A L P\) and \(P M B\), we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

\sin \theta & =\frac{k}{b} \dots(i) \\

\cos \theta & =\frac{h}{a} \dots(ii)

\end{aligned}

\)

Here \(\theta\) is a variable. So, we have to eliminate \(\theta\).

Squaring (i) and (ii) and adding, we get

\(

\frac{k^2}{b^2}+\frac{h^2}{a^2}=1

\)

Hence, the locus of \((h, k)\) is

\(

\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{b^2}=1

\)

Example 30: Two points \(P\) and \(Q\) are given, \(R\) is a variable point on one side of the line \(P Q\) such that \(\angle R P Q -\angle R Q P\) is a positive constant \(2 \alpha\). Find the locus of the point \(R\).

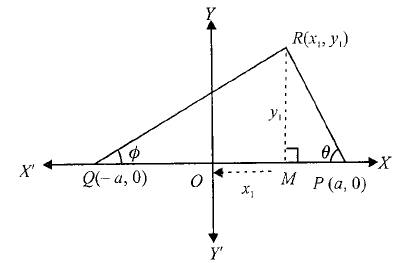

Solution: Let the \(x\)-axis along \(Q P\) and the middle point of \(P Q\) be origin and let \(R \equiv\left(x_1, y_1\right)\).

Let \(O P=O Q=a\) and \(\angle R P M=\theta\) and \(\angle R Q M=\phi\)

In \(\triangle R M P\),

\(

\tan \theta=\frac{R M}{M P}=\frac{y_1}{a-x_1} \dots(i)

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { In } \triangle R Q M \text {, }\\

&\tan \phi=\frac{R M}{Q M}=\frac{y_1}{a+x_1} \dots(ii)

\end{aligned}

\)

But given \(\angle R P Q-\angle R Q P=2 \alpha\) ( constant)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \theta-\phi=2 \alpha \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \tan (\theta-\phi)=\tan 2 \alpha \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{\tan \theta-\tan \phi}{1+\tan \theta \tan \phi}=\tan 2 \alpha \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{\frac{y_1}{a-x_1}-\frac{y_1}{a+x_1}}{1+\frac{y_1}{a-x_1} \frac{y_1}{a+x_1}}=\tan 2 \alpha \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{2 x_1 y_1}{a^2-x_1^2+y_1^2}=\tan 2 \alpha

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

=a^2 \Rightarrow a^2-x_1^2+y_1^2=2 x_1 y_1 \cot 2 \alpha \text { or } x_1^2-y_1^2+2 x_1 y_1 \cot 2 \alpha

\)

Hence, locus of the point \(R\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) is \(x^2-y^2+2 x y \cot 2 \alpha=a^2\).

Example 31: If the coordinates of a variable point \(P\) is \((\boldsymbol{a} \boldsymbol{\operatorname { c o s }} \theta, \boldsymbol{b} \boldsymbol{\operatorname { s i n }} \theta)\), where \(\theta\) is a variable quantity, then find the locus of \(P\).

Solution: Let \(P \equiv(x, y)\). According to the question

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=a \cos \theta \dots(i) \\

& y=b \sin \theta \dots(ii)

\end{aligned}

\)

Squaring and adding (i) and (ii), we get

\(

\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{b^2}=\cos ^2 \theta+\sin ^2 \theta

\)

\(

\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{b^2}=1

\)

Example 32: Find the locus of a point such that the sum of its distance from the points \((0,2)\) and \((0,-2)\) is 6.

Solution: Let \(P(h, k)\) be any point on the locus and let \(A(0,2)\) and \(\mathrm{B}(0,-2)\) be the given points.

By the given condition, we get

\(

P A+P B=6

\)

\(

\sqrt{(h-0)^2+(k-2)^2}+\sqrt{(h-0)^2+(k+2)^2}=6

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

\sqrt{h^2+(k-2)^2} & =6-\sqrt{(h-0)^2+(k+2)^2} \\

h^2+(k-2)^2 & =36-12 \sqrt{h^2+(k+2)^2}+h^2+(k+2)^2

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

-8 k-36 & =-12 \sqrt{h^2+(k+2)^2} \\

(2 k+9) & =3 \sqrt{h^2+(k+2)^2} \\

(2 k+9)^2 & =9\left(h^2+(k+2)^2\right) \\

4 k^2+36 k+81 & =9 h^2+9 k^2+36 k+36 \\

9 h^2+5 k^2 & =45

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, locus of \((h, k)\) is \(9 x^2+5 y^2=45\).

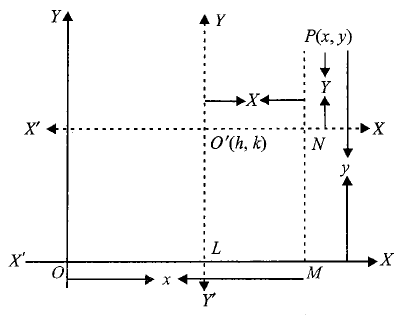

SHIFTING OF ORIGIN

Let \(O\) be the origin and let \(X^{\prime} O X\) and \(Y^{\prime} O Y\) be the axis of \(x\) and \(y\), respectively. Let \(O^{\prime}\) and \(P\) be two points in the plane having coordinates ( \(h, k\) ) and ( \(x, y\) ), respectively referred to \(X^{\prime} O X\) and \(Y^{\prime} O Y\) as the coordinates axes. Let the origin be transferred to \(O^{\prime}\) and let \(X^{\prime} O^{\prime} X\) and \(Y^{\prime} O^{\prime} Y\) be new rectangular axes. Let the coordinates of \(P\) referred to new axes as the coordinates axes be \((X, Y)\).

Then,

\(O^{\prime} N=X, P N=Y, O M=x, P M=y, O L=h\), and \(O^{\prime} L=k\)

Now,

\(

x=O M=O L+L M=O L+O^{\prime} N=h+X

\)

and

\(

\begin{aligned}

y & =P M=P N+N M=P N+O^{\prime} L=Y+k \\

\Rightarrow x & =X+h \text { and } y=Y+k

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus, if \((x, y)\) are coordinates of a point referred to old axes and \((X, Y)\) are the coordinates of the same point referred to new axes, then \(x=X+h\) and \(y=Y+k\). Therefore, the origin is shifted at a point \((h, k)\), we must substitute \(X+h\) and \(Y+k\) for \(x\) and \(y\), respectively.

The transformation formula from new axes to old axes is

\(

X=x-h, Y=y-k

\)

The coordinates of the old origin referred to the new axes are \((-h,-k)\).

Example 33: If the origin is shifted to the point \((1,-2)\) without rotation of axes what do the following equation become?

\(2 x^2+y^2-4 x+4 y=0\)

Solution: Substituting \(x=X+1, y=Y+(-2)=Y-2\) in the equation \(2 x^2+y^2-4 x+4 y=0\), we get

\(

2(X+1)^2+(Y-2)^2-4(X+1)+4(Y-2)=0

\)

or \(2 X^2+Y^2=6\)

Example 34: At what point the origin be shifted, if the coordinates of a point \((4,5)\) become \((-3,9)\) ?

Solution: Let \((h, k)\) be the point to which the origin is shifted. Then,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\therefore & x=4, y=5, X=-3, Y=9 \\

\Rightarrow & x=X+h \text { and } y=Y+k \\

\Rightarrow & 4=-3+h \text { and } 5=9+k \\

h=7 \text { and } k=-4

\end{array}

\)

Hence, the origin must be shifted to \((7,-4)\).

Example 35: Shift the origin to a suitable point so that the equation \(y^2+4 y+8 x-2=0\) will not contain term in \(y\) and the constant term.

Solution: Let the origin be shifted to \((h, k)\). Then,

\(

x=X+h \text { and } y=Y+k

\)

Substituting \(x=X+h, y=Y+k\) in the equation \(y^2+4 y +8 x-2=0\), we get

\(

\begin{aligned}

(Y+k)^2+4(Y+k)+8(X+h)-2 & =0 \\

\Rightarrow Y^2+(4+2 k) Y+8 X+\left(k^2+4 k+8 h-2\right) & =0

\end{aligned}

\)

For this equation to be free from the term containing \(Y\) and the constant term, we must have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& & 4+2 k & =0 \text { and } k^2+4 k+8 h-2=0 \\

\Rightarrow & & k & =-2 \text { and } h

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the origin is shifted at the point \((3 / 4,-2)\).

Example 36: The equation of a curve referred to new axes, axes retaining their directions, and origin \((4,5)\) is \(X^2 +Y^2=36\). Find the equation referred to the original axes.

Solution: With the above notation, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=X+4, y=Y+5 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad X=x-4, Y=y-5

\end{aligned}

\)

\(\therefore\) The required equation is

\(

(x-4)^2+(y-5)^2=36

\)

\(\Rightarrow x^2+y^2-8 x-10 y+5=0\) which is equation referred to the original axes.

Example 37: Find the equation to which the equation

\(

x^2+7 x y-2 y^2+17 x-26 y-60=0

\)

is transformed if the origin is shifted to the point ( \(2,-\) 3 ), the axes remaining parallel to the original axis.

Solution: Here the new origin is \((2,-3)\).

Then, \(x=X+2, y=Y-3\).

and the given equation transforms to

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (X+2)^2+7(X+2)(Y-3)-2(Y-3)^2+17(X+2)-26 \\

& (Y-3)-60=0 \\

& \Rightarrow X^2+7 X Y-2 Y^2-4=0

\end{aligned}

\)

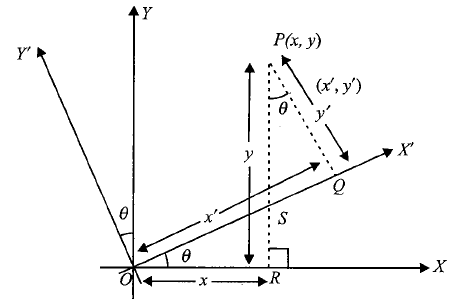

ROTATION OF AXIS

Rotation of Axes without Changing the Origin

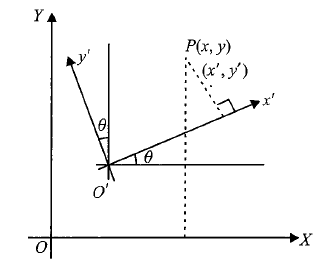

Let \(O\) be the origin. Let \(P \equiv(x, y)\) with respect to axes \(O X\) and \(O Y\) and let \(P \equiv\left(x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}\right)\) with respect to axes \(O X^{\prime}\) and \(O Y^{\prime}\) where \(\angle X^{\prime} O X=\angle Y O Y^{\prime}=\theta\)

In Figure above, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& S R=x \tan \theta, O S=x \sec \theta \\

& P S=y-x \tan \theta

\end{aligned}

\)

Now in triangle \(P Q S\),

\(

\begin{aligned}

\sin \theta & =\frac{S Q}{P S}=\frac{x^{\prime}-x \sec \theta}{y-x \tan \theta} \\

x^{\prime} & =y \sin \theta-x \frac{\sin ^2 \theta}{\cos \theta}+\frac{x}{\cos \theta} \\

& =y \sin \theta+x \frac{1-\sin ^2 \theta}{\cos \theta} \\

x^{\prime} & =x \cos \theta+y \sin \theta \\

\cos \theta & =\frac{P Q}{P S}=\frac{y^{\prime}}{y-x \tan \theta} \\

y^{\prime} & =-x \sin \theta+y \cos \theta \\

x & =x^{\prime} \cos \theta-y^{\prime} \sin \theta \\

y & =x^{\prime} \sin \theta+y^{\prime} \cos \theta

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{array}{|c|c|c|}

\hline & x & y \\

\hline x^{\prime} & \cos \theta & \sin \theta \\

\hline y^{\prime} & -\sin \theta & \cos \theta \\

\hline

\end{array}

\)

Note: Compare real and imaginary parts of the equation ( \(x +i y)=\left(x^{\prime}+i y^{\prime}\right)(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta)\) to remember the formula.

Example 38: The equation of a curve referred to a given system of axes is \(3 x^2+2 x y+3 y^2=10\). Find its equation if the axes are rotated through an angle \(45^{\circ}\), the origin remaining unchanged.

Solution: With the above notation, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=x^{\prime} \cos 45^{\circ}-y^{\prime} \sin 45^{\circ}=\frac{x^{\prime}-y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}} \\

& \text { and } y=x^{\prime} \sin 45^{\circ}+y^{\prime} \cos 45^{\circ}=\frac{x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus, \(3 x^2+2 x y+3 y^2=10\) transforms to

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 3\left(\frac{x^{\prime}-y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)^2+2\left(\frac{x^{\prime}-y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\left(\frac{x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)+3\left(\frac{x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)^2=10 \\

& \Rightarrow 2 x^{\prime 2}+y^{\prime 2}=5 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Removal of the term \(x y\), from \(f(x, y)=a x^2+ 2 h x y+b y^2\) without changing the origin

Clearly, \(h \neq 0\).

Rotating the axes through an angle \(\theta\), we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=x^{\prime} \cos \theta-y^{\prime} \sin \theta \\

& y=x^{\prime} \sin \theta+y^{\prime} \cos \theta . \\

& \therefore f(x, y)=a x^2+2 h x y+b y^2

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \quad=a\left(x^{\prime} \cos \theta-y^{\prime} \sin \theta\right)^2+2 h\left(x^{\prime} \cos \theta-\theta y^{\prime} \sin \theta\right) \cdot\left(x^{\prime} \sin \theta\right. \\

& \left.+y^{\prime} \cos \theta\right)+b\left(x^{\prime} \sin \theta+y^{\prime} \cos \theta\right)^2

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \quad=\left(a \cos ^2 \theta+2 h \cos \theta \sin \theta+b \sin ^2 \theta\right) x^{\prime 2}+2[(b-a) \cos \theta \\

& \left.\sin \theta+h\left(\cos ^2 \theta-\sin ^2 \theta\right)\right] x^{\prime} y^{\prime}+\left(a \sin ^2 \theta-2 h \cos \theta \sin \theta+b\right. \\

& \left.\cos ^2 \theta\right) y^{\prime 2}=F\left(x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}\right),(s a y)

\end{aligned}

\)

In \(F\left(x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}\right)\), we require that the coefficient of the \(X Y\)-term to be zero.

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \therefore 2\left[(b-a) \cos \theta \sin \theta+h\left(\cos ^2 \theta-\sin ^2 \theta\right)\right]=0 . \\

& \Rightarrow(a-b) \sin 2 \theta=2 h \cos 2 \theta . \\

& \Rightarrow \tan 2 \theta=\frac{2 h}{a-b} \text { or } \cot 2 \theta=\frac{a-b}{2 h}

\end{aligned}

\)

We use the former or the later equation according as \(a \neq b\) or \(a=b\). These yield \(\theta\), the angle through which the axes are to be rotated (the origin remaining unchanged) in order to remove the \(x y\)-term from \(f(x, y)\).

Example 39: Given the equation \(4 x^2+2 \sqrt{3} x y+2 y^2=1\). Through what angle should the axes be rotated so that the term \(x y\) is removed from the transformed equation.

Solution: Comparing the given equation, with \(a x^2+2 h x y+b y^2\), we get \(a=4, h=\sqrt{3}, b=2\).

Let \(\theta\) be the angle through which the axes are to be rotated.

Then \(\quad \tan 2 \theta=\frac{2 h}{a-b}\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad \tan 2 \theta=\frac{2 \sqrt{3}}{4-2}=\sqrt{3}=\tan \frac{\pi}{3}

\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\Rightarrow & 2 \theta=\frac{\pi}{3}, \pi+\frac{\pi}{3} \\

\Rightarrow & \theta=\frac{\pi}{6}, \frac{2 \pi}{3}

\end{array}

\)

Change of Origin and Rotation of Axes

If origin is changed to \(O^{\prime}(\alpha, \beta)\) and axes are rotated about the new origin \(O^{\prime}\) by an angle \(\theta\) in the anticlockwise sense such that the new coordiantes of \(P(x, y)\) becomes \(\left(x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}\right)\), then the equations of transformation will be

\(

x=\alpha+x^{\prime} \cos \theta-y^{\prime} \sin \theta

\)

and \(y=\beta+x^{\prime} \sin \theta+y^{\prime} \cos \theta\)

Example 40: What does the equation \(2 x^2+4 x y-5 y^2 +20 x-22 y-14=0\) become when referred to rectangular axes through the point ( \(-2,-3\) ), the new axes being inclined at an angle of \(45^{\circ}\) with the old axes?

Solution: Let \(O^{\prime}\) be \((-2,-3)\). Since the axes are rotated about \(O^{\prime}\) by an angle \(45^{\circ}\) in anticlockwise direction, let ( \(x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}\) ) be the new coordinates with respect to new axes and \((x, y)\) be the coordinates with respect to old axes. Then, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x=-2+x^{\prime} \cos 45^{\circ}-y^{\prime} \sin 45^{\circ}=-2+\left(\frac{x^{\prime}-y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right) \\

& y=-3+x^{\prime} \sin 45^{\circ}+y^{\prime} \cos 45^{\circ}=-3+\left(\frac{x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

The new equation will be

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 2\left(-2+\left(\frac{x^{\prime}-y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\right\}^2+4\left(-2+\left(\frac{x^{\prime}-y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\right)\left(-3+\left(\frac{x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\right) \\

& -5\left(-3+\left(\frac{x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\right)^2+20\left(-2+\left(\frac{x^{\prime}-y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\right) \\

& -22\left(-3+\left(\frac{x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\right)-14=0

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\Rightarrow \quad x^{\prime 2}-14 x^{\prime} y^{\prime}-7 y^{\prime 2}-2=0\\

&\text { Hence, new equation of curve is }\\

&x^2-14 x y-7 y^2-2=0

\end{aligned}

\)