1.6 Subsets and Superset

Subset

A set A is said to be a subset of set B if every element of \(\mathrm{A}\) is also an element of \(\mathrm{B}\). In symbols we write \(\mathrm{A} \subset \mathrm{B}\), if \(a \in \mathrm{A} \Rightarrow a \in \mathrm{B}\).

(i) consider sets, \(A=\{1,2,3,4\}\) and \(B=\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7\}\)

We observe that each element of set \(A\) is an element of set \(B\). In other words, all the elements of set \(A\) are also elements of set \(B\). Actually, set \(A\) is contained in the set \(B\).

(ii) Now, consider sets, \(A=\{x \mid x\) is a girl student in your class \(\}\), \(B=\{x \mid x\) is student in your class \(\}\)

Obviously, each girl student in your class is student of your dass. Thus, set \(A\) is contained in set \(B\).

In both of the above cases, set \(A\) is called the subset of \(B\). Mathematically, it is written as \(A \subseteq B\).

Thus. \(A \subseteq B \Leftrightarrow x \in A \Rightarrow x \in B\).

Here. \(\subseteq\) symbolizes the subset or equal sets.

(iii) Now, consider sets \(A=\{1,2,3\}\) and \(B=\{2,3,1\}\).

Here, sets \(A\) and \(B\) are equal or coincide. We can write \(A=B\) or \(A \subseteq B\) or \(B \subseteq A\).

If at least one element of the set \(A\) is not the element of the set \(B\), then \(A\) not a subset of \(B\) i.e., \(A \not \subset B\).

Example 1: \(A=\{1,2,3\}, \quad B=\{1,2,3,4\}\), In this example, all the elements of set A are in Set B. Therefore we can say set A is a subset of B. \(\mathrm{A} \subset \mathrm{B}\) In this case, we can not say B is a subset of A because all the elements in set B is not present in set A. In this case, we say B is a superset of A.

Proper Subset of a Set

Set \(A\) is said to be a proper subset of set \(B\) if \(A\) is a subset of \(B\) and \(A \neq B\).

This fact is expressed by writing \(A \subset B\) or \(B \supset A\) (read as ‘ \(A\) is a proper subset of \(B\) or \(B\) is a superset of \(A\) ‘. )

Thus, the number of elements in \(B\) is greater than that in \(A\). we say \(B\) is a superset of \(A\).

For example,

(i) Let \(A=\{1,2,3\}, B=\{2,3,4,1,5\}\). Then \(A \subset B\) or \(B \supset A\).

(ii) \(N \subset Z \subset Q \subset R\)

Equality of Sets

Two sets \(A\) and \(B\) are equal if \(A\) is a subset of \(B\) and \(B\) is a subset of \(A\).

Thus, \(A=B \Leftrightarrow A \subseteq B\) and \(B \subseteq A\).

Note: \(A \subset B \Leftrightarrow A \subseteq B \text { and } A \neq B\)

Superset of a Set

A set \(A\) is said to be a superset of set \(B\), if \(B\) is a subset of \(A\) i.e., each element of \(B\) is an element of \(A\). If \(A\) is a superset of \(B\), we write \(A \supseteq B\).

The statement \(B \subseteq A\) can also be expressed equivalently by writing \(A \supseteq B\) (read as ‘ \(A\) is a superset of \(B\) ‘ ).

Note: An important point to remember is that any set is a subset of itself. Also null set is a subset of every set.

We denote set of real numbers by \(\mathbf{R}:\{\pi,1,3\cdots\}\)

set of natural numbers by \(\mathbf{N}:\{1,2,3,4,5 \ldots\}\)

set of integers by \(\mathbf{Z}:\{-7,-6,-5,1,4,5, . .\}\)

set of rational numbers by \(\mathbf{Q}:\{1.2,1.3,1.5,2.2 \ldots\}\)

set of irrational numbers by \(\mathbf{T}:\{\pi=3 \cdot 14159265 \ldots, \sqrt{2}=1 \cdot 414213 \cdots\}\)

We observe that,

\(\begin{aligned}&\mathbf{N} \subset \mathbf{Z} \subset \mathbf{Q} \subset \mathbf{R} \\&\mathbf{T} \subset \mathbf{R}, \mathbf{Q} \not \subset \mathbf{T}, \mathbf{N} \not \subset \mathbf{T}\end{aligned}\)

Let us consider a few examples

(i) Let \(\mathrm{A}=\{1,3,5\}\) and \(\mathrm{B}=\{x: x\) is an odd natural number less than 6\(\}\). Then \(\mathrm{A} \subset \mathrm{B}\) and \(\mathrm{B} \subset \mathrm{A}\) and hence \(\mathrm{A}=\mathrm{B}\).

(ii) Let \(\mathrm{A}=\{a, e, i, o, u\}\) and \(\mathrm{B}=\{a, b, c, d\}\). Then \(\mathrm{A}\) is not a subset of \(\mathrm{B}\), also \(\mathrm{B}\) is not a subset of \(\mathrm{A}\).

(iii) Let \(\mathrm{A}\) and \(\mathrm{B}\) be two sets. If \(\mathrm{A} \subset \mathrm{B}\) and \(\mathrm{A} \neq \mathrm{B}\), then \(\mathrm{A}\) is called a proper subset of \(\mathrm{B}\) and \(\mathrm{B}\) is called superset of \(\mathrm{A}\). For example, \(\mathrm{A}=\{1,2,3\}\) is a proper subset of \(\mathrm{B}=\{1,2,3,4\}\). If a set \(\mathrm{A}\) has only one element, we call it a singleton set. Thus, \(\{a\}\) is a singleton set.

Example 2: If \(A \not \subset B\) and \(B \not \subset C\) then \(A \not \subset C\). Is this statement true?

Solution: Let \(A=\{1,2\}, B=\{0,6,8\}\), and \(C=\{0,1,2,6,9\}\) Here, \(A \not \subset B\) and \(B \not \subset C\), but \(A \subset C\).

So, the given statement is false.

Example 3: If \(x \in A\) and \(A \not \subset B\), then \(x \in B\). Is this statement true?

Solution: Let \(A=\{3,5,7\}\) and \(B=\{3,4,6\}\)

Now, \(5 \in A\) and \(A \not \subset B\)

However, \(5 \notin B\)

So, the given statement is false.

Example 4: Consider the sets

\(

\phi, \mathrm{A}=\{1,3\}, \quad \mathrm{B}=\{1,5,9\}, \quad \mathrm{C}=\{1,3,5,7,9\} \text {. }

\)

Insert the symbol \(\subset\) or \(\not \subset\) between each of the following pair of sets:

(i) \(\phi \ldots B\)

(ii) A… B

(iii) A…C

(iv) B …C

Solution:

(i) \(\phi \subset \mathrm{B}\) as \(\phi\) is a subset of every set.

(ii) \(\mathrm{A} \not \subset \mathrm{B}\) as \(3 \in \mathrm{A}\) and \(3 \notin \mathrm{B}\)

(iii) \(\mathrm{A} \subset \mathrm{C}\) as \(1,3 \in \mathrm{A}\) also belongs to \(\mathrm{C}\)

(iv) \(\mathrm{B} \subset \mathrm{C}\) as each element of \(\mathrm{B}\) is also an element of \(\mathrm{C}\).

Example 5: Let \(A, B\) and \(C\) be three sets. If \(A \in B\) and \(B \subset C\), is it true that \(\mathrm{A} \subset \mathrm{C}\)?. If not, give an example.

Solution: No. Let \(\mathrm{A}=\{1\}, \mathrm{B}=\{\{1\}, 2\}\) and \(\mathrm{C}=\{\{1\}, 2,3\}\). Here \(\mathrm{A} \in \mathrm{B}\) as \(\mathrm{A}=\{1\}\) and \(\mathrm{B} \subset \mathrm{C}\).

But \(\mathrm{A} \not \subset \mathrm{C}\) as \(1 \in \mathrm{A}\) and \(1 \notin \mathrm{C}\).

Note that an element of a set can never be a subset of itself.

Intervals as subsets of \(R\):

We know that \(R\) is the set of all real numbers. Now, let us define different subsets of \(R\).

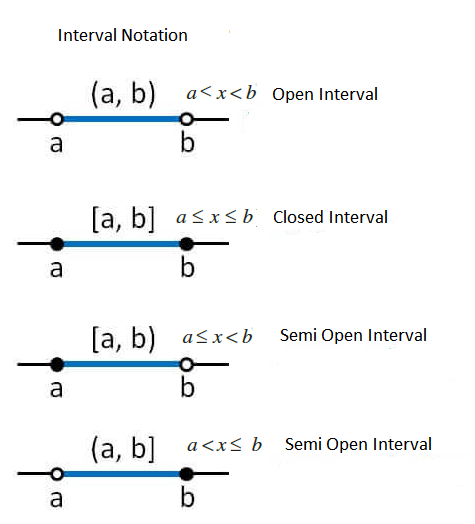

Open interval and closed interval are used to represent a range of numeric values. The open interval includes only the values between the endpoints and is represented as ( ). The closed interval includes even the endpoints of the range of values and is represented as [ ]. The open interval can be presented as an expression \(a<x<b\), and the closed interval is represented as an expression \(a \leq x \leq b\).

Open interval

Open interval is the one in which the endpoints are not included. The numbers are written as ordered pair between plain brackets i.e open interval, a to \(b\) open is written as \((a, b)\). Every real number from \(a\) to \(b\) is included except \(a\) and \(b\) itself. We get an open interval when we use an inequality like

- \(<\) less than

- \(>\) greater than

Example 6: All values of \(x\) greater than \(-3\) and less than 5 are between \(-3\) and 5 but \(-3\) and 5 are not included \(x \in(-3,5)\). We can write it as

\(-3<x<5 \text { or } x \in(-3,5)\)Closed interval

Closed interval is the one in which endpoints are included. The numbers are written as pair between square bracket i.e Closed from a to b and is written as [a, b]. Every real number from a to \(b\) including \(a\) and \(b\) are included. Closed interval is used while writing inequalities

- \(\leq\) less than or equal to

- \(\geq\) greater than or equal to.

Example 7: All values of \(x\) greater than or equal to \(-3\) and less than or equal to 5. In this both \(-3\) and 5 are included, is written as \(x \in[-3,5]\). We can write it as

\(-3 \leq x \leq 5 \quad \text { Or } \quad x \in[-3,5]\)Example 8: The expression \(2<x<6\) (does not include the end points 2 and 6), represents an open interval, and the expression \(\mathrm{2} \leq \mathrm{x} \leq \mathrm{6}\) (includes the end points 2 and 6) represents a closed interval.

Let \(a, b \in \mathrm{R}\) and \(a<b\). Then

(a) An open interval denoted by \((a, b)\) is the set of real numbers \(\{x: a<x<b\}\). All the points between \(a\) and \(b\) belong to the open interval \((a, b)\) but \(a, b\) themselves do not belong to this interval.

(b) A closed interval denoted by \([a, b]\) is the set of real numbers \(\{x: a \leq x \leq b)\)

(c) Intervals closed at one end and open at the other are given by

\(

\begin{aligned}

&{[a, b)=\{x: a \leq x<b\}} \text { is an open interval from } a \text { to } b \text {, including } a \text { but excluding } b \text {. }\\

&(a, b]=\{x: a<x \leq b\} \text { is an open interval from } a \text { to } b \text { including } b \text { but excluding } a \text {. }

\end{aligned}

\)

On the real number line, various types of intervals described above as subsets of R, are shown in the figure below.

The number ( \(b-a\) ) is called the length of any of the intervals \((a, b),[a, b],[a, b)\) or \((a, b]\).

Clearly, \((a, b) \subset[a, b]\) but \([a, b] \not \subset(a, b)\).

The set \(\{x \mid x \in R,-6<x \leq 9\}\), written in set-builder form, can be written in the form of interval as \((-6,9]\) and the interval \([-2,5)\) can be written in set builder form as \(\{x \mid-2 \leq x<5\}\).

Note:

- The set \((-\infty, \infty)\) defines the set of all real numbers extending from \(-\infty\) to \(\infty\).

- The set \((0, \infty)\) defines the set of all positive real numbers denoted by \(R^{+}\).

- The set \((-\infty, 0)\) defines the set of all negative real numbers denoted by \(R^{-}\).

- The set \([0, \infty)\) defines the set of all non-negative real numbers \(R^{+} \cup\{0\}\).

- The set \((-\infty, 0]\) defines the set of all non-positive real numbers \(R^{-} \cup\{0\}\).

- Complement of interval \((a, b)\) is \((-\infty, a] \cup[b, \infty)\).

- Complement of interval \([a, b]\) is \((-\infty, a) \cup(b, \infty)\).

Example 9: Write as intervals :\(\{x: x \in R,-4<x \leq 6\}\)

Solution: \((-4,6]\) (-4 not included, so it should be open and 6 included, so it should be closed)

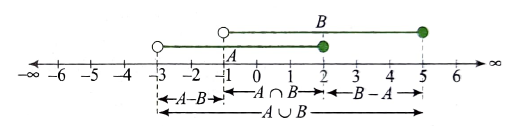

Example 10: If sets \(A=(-3,2]\) and \(B=(-1,5]\), then find the following sets:

(i) \(A \cap B\)

(ii) \(A \cup B\)

(iii) \(A-B\)

(iv) \(B-A\)

Solution: We have sets \(A=(-3,2]\) and \(B=(-1,5]\)

These sets are plotted on the real number line as shown in the following figure.

From the figure

(i) \(A \cap B=(-1,2]\) (as \(-1 \in A\) but \(-1 \notin B\) )

(ii) \(A \cup B=(-3,5]\)

(iii) \(A-B=(-3,-1] \quad\) (as \(-1 \notin B\), so \(-1 \in A-B)\)

(iv) \(B-A=(2,5] \quad(\) as \(2 \in A\), so \(2 \notin B-A)\)