1.11 Complement of a Set

Complement of a set

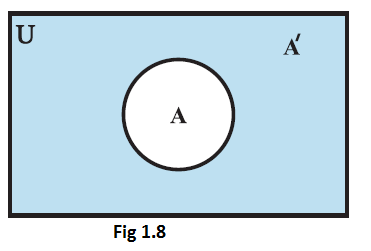

Let \(\mathrm{U}\) be the universal set and A a subset of \(\mathrm{U}\). Then the complement of \(\mathrm{A}\) is the set of all elements of \(\mathrm{U}\) which are not the elements of \(\mathrm{A}\). It is denoted by \(A^c\) or \(A^{\prime}\). Symbolically, we write

\(

\mathrm{A}^{\prime}=\{x: x \in \mathrm{U} \text { and } x \notin \mathrm{A}\} . \mathrm{Also} \mathrm{~A}^{\prime}=\mathrm{U}-\mathrm{A}

\)

For example, if set \(U=\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10\}\) and set \(A=\{1,2,5,7,9\}\) then set \(A^{\prime}=\{3,4,6,8,10\}\).

Clearly, \(A^{\prime}=U-A\).

Symbolically, set \(A^{\prime}=\{x \mid x \in U\) and \(x \notin A\}\)

Thus, if \(x \in A \Leftrightarrow x \notin A^{\prime}\).

Properties of the complement of sets

- \(A \cap A^{\prime}=\phi\left(\right.\) as nothing is common between \(A\) and \(\left.A^{\prime}\right)\)

- \(A \cup A^{\prime}=U\)

- \(U^{\prime}=\phi\)

- \(\phi^{\prime}=\mathrm{U}\)

- \(\left(A^{\prime}\right)^{\prime}=A\)

- \(A \subseteq B \Leftrightarrow B^{\prime} \subseteq A^{\prime}\)

- \(A-B=B^{\prime}-A^{\prime}\)

- \(A-B=A \cap B^{\prime}\)

- \(B-A=A^{\prime} \cap B\)

Complement and the word ‘not’

The word ‘not’ corresponds to the complement of a set.

For example, let set \(V=\{\) letters that are vowel \(\}\)

Then complement of set \(V\) is \(V^{\prime}=\{\) letters that are not vowels \(\}\)

\(=\{\) letters that are consonants \(\}\)

De Morgan’s laws

The complement of the union of two sets is the intersection of their complements, and the complement of the intersection of two sets is the union of their complements. These are named after the mathematician De Morgan.

(i) \((A \cup B)^{\prime}=A^{\prime} \cap B^{\prime}\)

(ii) \((A \cap B)^{\prime}=A^{\prime} \cup B^{\prime}\)

(iii) \(A-(B \cup C)=(A-B) \cap(A-C)\)

(iv) \(A-(B \cap C)=(A-B) \cup(A-C)\)

The complement \(\mathrm{A}^{\prime}\) of a set \(\mathrm{A}\) can be represented by a Venn diagram as shown in Fig. 1.8. The shaded portion represents the complement of the set \(\mathrm{A}\).

Venn Diagrams of Operations of Sets

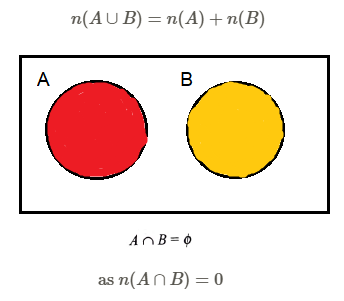

Case I: \(A\) and \(B\) are disjoint.

Here, the shaded part represents \(A \cup B\).

The unshaded part represents \((A \cup B)^{\prime}\) or \(A^{\prime} \cap B^{\prime}\).

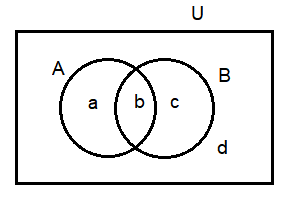

Case II: \(A \cap B \neq \phi\)

Here region ‘ \(b\) ‘ represents \(A \cap B\).

Region ‘ \(a\) ‘ represents \(A \cap B^{\prime}\) or \(A-B\).

Region ‘ \(c\) ‘ represents \(A^{\prime} \cap B\) or \(B-A\).

Regions ‘ \(a\) ‘, ‘ \(b\) ‘ and ‘ \(c\) ‘ collectively represent \(A \cup B\).

Region ‘ \(d\) ‘ represents \((A \cup B)^{\prime}\) or \(A^{\prime} \cap B^{\prime}\).

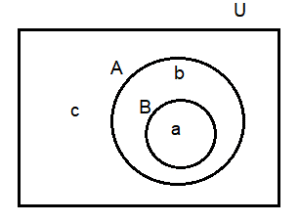

Case III: \(B \subset A\)

Here, set \(A\) represents \(A \cup B\).

Set \(B\) represents \(A \cap B\).

Region ‘ \(b\) ‘(outside set \(B\) but inside set \(A\) ) represents \(A \cap B^{\prime}\) or \(A-B\).

Region ‘ \(c\) ‘ represents \((A \cup B)^{\prime}\) or \(A^{\prime} \cap B^{\prime}\).

Example 1:

Let \(\mathrm{U}=\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10\}\) and \(\mathrm{A}=\{1,3,5,7,9\}\). Find \(\mathrm{A}^{\prime}\).

Solution: We note that \(2,4,6,8,10\) are the only elements of \(\mathrm{U}\) which do not belong to A. Hence \(\mathrm{A}^{\prime}=\{2,4,6,8,10\}\).

Example 2:

Let \(\mathrm{U}=\{1,2,3,4,5,6\}, \mathrm{A}=\{2,3\}\) and \(\mathrm{B}=\{3,4,5\}\). Find \(\mathrm{A}^{\prime}, \mathrm{B}^{\prime}, \mathrm{A}^{\prime} \cap \mathrm{B}^{\prime}, \mathrm{A} \cup \mathrm{B}\) and hence show that \((\mathrm{A} \cup \mathrm{B})^{\prime}=\mathrm{A}^{\prime} \cap \mathrm{B}^{\prime}\).

Solution: Clearly \(\mathrm{A}^{\prime}=\{1,4,5,6\}, \mathrm{B}^{\prime}=\{1,2,6\}\). Hence \(\mathrm{A}^{\prime} \cap \mathrm{B}^{\prime}=\{1,6\}\)

Also \(\mathrm{A} \cup \mathrm{B}=\{2,3,4,5\}\), so that \((\mathrm{A} \cup \mathrm{B})^{\prime}=\{1,6\}\)

\((\mathrm{A} \cup \mathrm{B})^{\prime}=\{1,6\}=\mathrm{A}^{\prime} \cap \mathrm{B}^{\prime}\)

It can be shown that the above result is true in general. If \(\mathrm{A}\) and \(\mathrm{B}\) are any two subsets of the universal set \(\mathrm{U}\), then

\((\mathrm{A} \cup \mathrm{B})^{\prime}=\mathrm{A}^{\prime} \cap \mathrm{B}^{\prime}\). Similarly, \((\mathrm{A} \cap \mathrm{B})^{\prime}=\mathrm{A}^{\prime} \cup \mathrm{B}^{\prime}\).

Example 3: Consider the following sets:

\(A=\) set of natural numbers which are multiples of 2

\(B=\) set of natural numbers which are multiples of 3

\(C=\) set of natural numbers which are multiples of 5. Then find the following sets:

(i) \(A \cup B\)

(ii) \(B \cup C\)

(iii) \(A-B\)

(iv) \(B-C\)

(v) \(A \cap C\)

(vi) \(A \cap B \cap C\)

(vii) \((A \cup B)-C\)

Solution: We have

\(A=\) set of natural numbers which are multiples of 2

\(B=\) set of natural numbers which are multiples of 3

\(C=\) set of natural numbers which are multiples of 5

\(

\begin{aligned}

A \cup B= & \text { set of natural numbers which are multiples of } 2 \text { or } 3 \\

= & \{2,3,4,6,8,9,10,12,14,15,16,18,20,21, \ldots\} \\

B \cup C= & \text { set of natural numbers which are multiples of } 3 \text { or } 5 \\

= & \{3,5,6,9,10,12,15,18,20, \ldots\} \\

A-B= & \{2,4,6,8,10,12,14,16,18, \ldots\} \\

& -\{3,6,9,12,15,18, \ldots\} \\

= & \text { set of natural numbers which are multiples of } 2 \text { but } \\

& \text { not multiples of } 3 \\

= & \{2,4,8,10,14,16,20, \ldots\}

\end{aligned}

\)

In this set. elements \(6,12,18, \ldots\) are excluded which are multiples of 2 and 3 both.

Similarly.

\(

\begin{aligned}

B-C & =\{3,6,9,12,15,18,21,24,27,30, \ldots\} \\

& -\{5,10,15,20,25,30, \ldots\} \\

& =\{3,6,9,12,18,21,24,27,33, \ldots\}

\end{aligned}

\)

In this set. elements \(15,30, \ldots\) are excluded which are multiples of 3 and 5 both.

\(

\begin{aligned}

A \cap C= & \text { set of natural numbers which are multiples of } 2 \text { and } 5 \text { both } \\

= & \text { set of natural numbers which are multiples of } 10 \\

= & \{10,20,30,40,50 \ldots\}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(A \cap B \cap C=\) set of natural numbers which are multiples of 2, 3 and 5

\(=\) set of natural numbers which are multiples of 30

\(=\{30,60,90,120,150, \ldots\}\)

\((A \cup B)-C=\) set of natural numbers which are multiples of 2 or 3 but not 5

\(

=\{2,3,4,6,8,9,12,14,16,18,21, \ldots\}

\)

In this set, elements \(5,10,15,20,25,30, \ldots\) are excluded.

Example 4: If \(A-B=A\) and \(B-A=B\), then what can we conclude?

Solution: We have \(A-B=A\), which means that no element of set \(A\) is common with elements of set \(B\).

Also, \(B-A=B\), which means no element of set \(B\) is common with elements of set \(A\).

So, \(A \cap B=\phi\), i.e., sets \(A\) and \(B\) are disjoint.

Example 5: If \(A \cap B=A \cup B\), then what can we conclude?

Solution: We have \(A \cap B=A \cup B\)

Consider the following cases:

(i) \(A \subset B\)

For this case, \(A \cap B=A\) and \(A \cup B=B\). So,

\(

A \cap B \neq A \cup B

\)

(ii) \(B \subset A\)

For this case, \(A \cap B=B\) and \(A \cup B=A\). So,

\(

A \cap B \neq A \cup B

\)

(iii) \(A\) and \(B\) are disjoint

For this case, \(A \cap B=\phi\) and \(A \cup B=\) set of all elements of set \(A\) and set \(B\).

So, \(A \cap B \neq A \cup B\)

(iv) Sets \(A\) and \(B\) have some elements common

For this case, \(A \cap B\) have some elements but \(A \cup B\) is the set of elements of set \(A\) and set \(B\).

So, \(A \cap B \neq A \cup B\)

From the above cases, we conclude that sets \(A\) and \(B\) are same. So, \(A=B\).

Example 6: Show that \(A \cap B=A \cap C\) need not imply \(B=C\).

Solution: Let \(A=\{0,1\}, B=\{0,2,3\}\), and \(C=\{0,4,5\}\)

Accordingly, \(A \cap B=\{0\}\) and \(A \cap C=\{0\}\)

Here, \(A \cap B=A \cap C=\{0\}\)

However, \(B \neq C(2 \in B\) and \(2 \notin C)\)

Example 7: Consider the following sets:

\(A=\) set of all rectangles in the plane

\(B=\) set of all squares in the same plane

\(C=\) set of all parallelograms in the same plane

Find the following sets:

(i) \(A-B\)

(ii) \(C-A\)

(iii) \(A \cap C\)

(iv) \(B \cap C\)

(v) \(B \cup C\)

(vi) \(A \cap B \cap C\)

Solution: We have

\(A\) – set of all rectangles in the same plane

\(B\) – set of all squares in the same plane

\(C\) – set of all parallelograms in the same plane

Since all squares are rectangles, \(B \subseteq A\).

Also, all squares and rectangles are parallelograms.

So, \(A, B \subseteq C\)

\(

\therefore B \subseteq A \subseteq C

\)

(i) \(A-B=\) set of all rectangles which are not squares

(ii) \(C-A=\) set of all parallelograms which are not rectangles or squares

\(=\) set of all parallelograms which are not rectangles

(iii) \(A \cap C=\) set of all rectangles \(=A\)

(iv) \(B \cap C=\) set of all squares \(=B\)

(v) \(B \cup C=\) set of all parallelograms \(=C\)

(vi) \(A \cap B \cap C=\) set of all squares \(=B\)

Example 8: Show that if \(\mathrm{A} \subset \mathrm{B}\), then \(\mathrm{C}-\mathrm{B} \subset \mathrm{C}-\mathrm{A}\).

Solution: Let \(A \subset B\)

We have to show that \(C-B \subset C-A\)

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\text { Let } & x \in C-B \\

\Rightarrow & x \in C \text { and } x \in B \\

\Rightarrow & x \in C \text { and } x \in A[\because \quad A \subset B] \\

\Rightarrow & x \in C-A \\

\therefore & C-B \subset C-A

\end{array}

\)

Example 9: Assume that \(P(A)=P(B)\). Then show that \(A=B\).

Solution: Suppose \(A \neq B\).

Without loss of generality, there exists \(x \in A\) such that \(x \notin B\).

Then \(\{x\} \in P(A)\) whereas, \(\{x\} \notin P(B)\).

Thus, \(P(A) \neq P(B)\), which contradicts the given condition.

So, \(A=B\).

Conversely, if \(P(A)=P(B)\) then all their singletons are the same. Thus, \(A=B\).