Past JEE PYQs

Summary

- Two real numbers or two algebraic expressions related by the symbols \(<,>, \leq\) or \(\geq\) form an inequality.

- Equal numbers may be added to (or subtracted from ) both sides of an inequality.

- Both sides of an inequality can be multiplied (or divided) by the same positive number. But when both sides are multiplied (or divided) by a negative number, then the inequality is reversed.

- The values of \(x\), which make an inequality a true statement, are called solutions of the inequality.

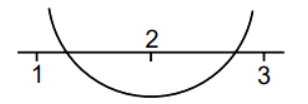

- To represent \(x<a\) (or \(x>a\) ) on a number line, put a circle on the number \(a\) and dark line to the left (or right) of the number \(a\).

- To represent \(x \leq a\) (or \(x \geq a\) ) on a number line, put a dark circle on the number \(a\) and dark the line to the left (or right) of the number \(x\).

- \(a \leq b\) either \(a<b\) or \(a=b\)

- \(a<b\) and \(b<c \Rightarrow a<c\) (transition property)

- \(a<b \Rightarrow-a>-b\), i.e., inequality sign reverses if both sides are multiplied by a negative number

- \(a<b\) and \(c<d \Rightarrow a+c<b+d\) and \(a-d<b-c\).

- If both sides of inequality are multiplied (or divided) by a positive number, inequality does not change. When both of its sides are multiplied (or divided) by a negative number, inequality gets reversed.

i.e., \(a<b \Rightarrow k a<k b\) if \(k>0\) and \(k a>k b\) if \(k<0\) - \(0<a<b \Rightarrow a^r<b^r\) if \(r>0\) and \(a^r>b^r\) if \(r<0\)

- \(a+\frac{1}{a} \geq 2\) for \(a>0\) and equality holds for \(a=1\)

- \(a+\frac{1}{a} \leq-2\) for \(a<0\) and equality holds for \(a=-1\)

- Squaring an inequality:

If \(a<b\), then \(a^2<b^2\) does not follows always:

Consider the following illustrations:

\(2<3 \Rightarrow 4<9\), but \(-4<3 \Rightarrow 16>9\)

Also if \(x>2 \Rightarrow x^2>4\), but for \(x<2 \Rightarrow x^2 \geq 0\)

If \(2<x<4 \Rightarrow 4<x^2<16\)

If \(-2<x<4 \Rightarrow 0 \leq x^2<16\)

If \(-5<x<4 \Rightarrow 0 \leq x^2<25\)

In fact \(a<b \Rightarrow a^2<b^2\) follows only when absolute value of \(a\) is less than the absolute value of \(b\) or distance of \(a\) from zero is less than the distance of \(b\) from zero on real number line. - Law of reciprocal:

If both sides of inequality have same sign, while taking its reciprocal the sign of inequality gets reversed. i.e., \(a\). \(>b>0 \Rightarrow \frac{1}{a}<\frac{1}{b}\) and \(a<b<0 \Rightarrow \frac{1}{a}>\frac{1}{b}\)

But if both sides of inequality have opposite sign, then while taking reciprocal sign of inequality does not change, i.e.

\(

a<0<b \Rightarrow \frac{1}{a}<\frac{1}{b}

\)

If \(x \in[a, b] \Rightarrow\left\{\begin{array}{l}\frac{1}{x} \in\left[\frac{1}{b}, \frac{1}{a}\right], \text { if } a \text { and } b \text { have same sign } \\ \frac{1}{x} \in\left(-\infty, \frac{1}{a}\right] \cup\left[\frac{1}{b}, \infty\right), \text { if } a \text { and } b \text { have opposite signs }\end{array}\right.\) - \(|x|<a \Leftrightarrow-a<x<a\) i.e. \(x \in(-a, a)\)

- \(|x| \leq a \Leftrightarrow-a \leq x \leq a\) i.e. \(x \in[-a, a]\)

- \(|x|>a \Leftrightarrow x<-a\) or \(x>a\) i.e. \(x \in(-\infty,-a) \cup(a, \infty)\)

- \(|x| \geq a \Leftrightarrow x \leq-a\) or \(x \geq a\) i.e. \(x \in(-\infty,-a] \cup[a, \infty)\)

If \(r\) is a positive real number and \(a\) is any real number, then

- \(|x-a|<r \Leftrightarrow a-r<x<a+r\) i.e. \(x \in(a-r, a+r)\)

- \(|x-a| \leq r \Leftrightarrow a-r \leq x \leq a+r\) i.e. \(x \in[a-r, a+r]\)

- \(|x-a|>r \Leftrightarrow x<a-r\) or, \(x>a+r\)

\(

\text { i.e. } x \in(-\infty, a-r) \cup(a+r, \infty)

\) - \(|x-a| \geq r \Leftrightarrow x \leq a-r\) or, \(x \geq a+r\)

\(

\text { i.e. } x \in(-\infty, a-r] \cup[a+r, \infty)

\)

If \(a, b>0\) and \(c\) are real numbers, then

- \(a<|x|<b \Leftrightarrow x \in(-b,-a) \cup(a, b)\)

- \(a \leq|x| \leq b \Leftrightarrow x \in[-b,-a] \cup[a, b]\)

- \(a \leq|x-c| \leq b \Leftrightarrow x \in[-b+c,-a+c] \cup[a+c, b+c]\)

- \(a<|x-c|<b \Leftrightarrow x \in(-b+c,-a+c) \cup(a+c, b+c)\)

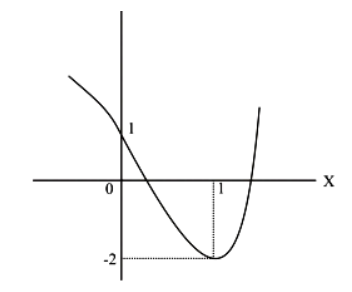

- If \(a, b, c \in R\) such that \(b^2-4 a c<0\), then

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a>0 \Rightarrow a x^2+b x+c>0 \text { for all } x \in R \\

& a<0 \Rightarrow a x^2+b x+c<0 \text { for all } x \in R

\end{aligned}

\)

i.e. \(a x^2+b x+c\) and \(a\) are of the same sign for all \(x \in R\).

Quadratic Equation

An equation of the form

\(

a x^2+b x+c=0 \dots(i)

\)

where \(a \neq 0, a, b, c \in R\) is called a quadratic equation with real coefficients.

The quantity \(D=b^2-4 a c\) is known as the discriminant of the quadratic equation in (i) whose roots are given by

\(

\alpha=\frac{-b+\sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a} \text { and } \beta=\frac{-b-\sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}

\)

Where \(\alpha, \beta\) are roots of the quadratic equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\), then

\(

\alpha+\beta=-\frac{b}{a} \text { and } \alpha \beta=\frac{c}{a}

\)

The nature of the roots is as given below :

- The roots are real and distinct iff \(D>0\).

- The roots are real and equal iff \(D=0\).

- The roots are complex with non-zero imaginary part iff \(D<0\).

- The roots are rational iff \(a, b, c\) are rational and \(D\) is a perfect square.

- The roots are of the form \(p+\sqrt{q}(p, q \in Q)\) iff \(a, b, c\) are rational and \(D\) is not a perfect square.

- If \(a=1, b, c \in I\) and the roots are rational numbers, then these roots must be integers.

- If a quadratic equation in \(x\) has more than two roots, then it is an identity in \(x\) that is \(a=b=c=0\).

Quiz Summary

0 of 101 Questions completed

Questions:

Information

You have already completed the quiz before. Hence you can not start it again.

Quiz is loading…

You must sign in or sign up to start the quiz.

You must first complete the following:

Results

Results

0 of 101 Questions answered correctly

Your time:

Time has elapsed

You have reached 0 of 0 point(s), (0)

Earned Point(s): 0 of 0, (0)

0 Essay(s) Pending (Possible Point(s): 0)

Categories

- Not categorized 0%

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- Current

- Review

- Answered

- Correct

- Incorrect

-

Question 1 of 101

1. Question

The sum of the squares of the roots of \(|x-2|^2+|x-2|-2=0\) and the squares of the roots of \(x^2-2|x-3|-5=0\), is [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 8th April Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(c) Let the roots of the first equation be \(x_1\) and \(x_2\). Let the roots of the second equation be \(x_3\) and \(x_4\). We need to find the value of \(x_1^2+x_2^2+x_3^2+x_4^2\).

Step 1: Solve the first equation

The first equation is \(|x-2|^2+|x-2|-2=0\).

Let \(y=|x-2|\). The equation becomes \(y^2+y-2=0\).

Factoring the quadratic equation gives \((y+2)(y-1)=0\).

This yields two possible values for \(y: y=-2\) or \(y=1\).

Since \(y=|x-2|\), it must be non-negative. Therefore, we only consider \(y=1\).

\(|x-2|=1\) implies \(x-2=1\) or \(x-2=-1\).

The roots are \(x_1=3\) and \(x_2=1\).

The sum of the squares of these roots is \(x_1^2+x_2^2=3^2+1^2=9+1=10\).

Step 2: Solve the second equation

The second equation is \(x^2-2|x-3|-5=0\).

We consider two cases based on the sign of \(x-3\).

Case 1: \(\boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{\geq} \mathbf{3}\)

In this case, \(|x-3|=x-3\).

The equation becomes \(x^2-2(x-3)-5=0\), which simplifies to \(x^2-2 x+1=0\).

This is \((x-1)^2=0\), giving \(x=1\).

However, this solution violates the condition \(x \geq 3\), so it is not a valid root.

Case 2: \(x<3\)

In this case, \(|x-3|=-(x-3)=3-x\).

The equation becomes \(x^2-2(3-x)-5=0\), which simplifies to \(x^2+2 x-11=0\).

We use the quadratic formula \(x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}\) to find the roots.

Here, \(a=1, b=2\), and \(c=-11\).

The roots are \(x_3=-1+2 \sqrt{3}\) and \(x_4=-1-2 \sqrt{3}\).

Both roots are less than 3, so they are valid.

The sum of the squares of these roots is \(x_3^2+x_4^2=(-1+2 \sqrt{3})^2+(-1-2 \sqrt{3})^2\).

\(

x_3^2+x_4^2=(1-4 \sqrt{3}+12)+(1+4 \sqrt{3}+12)=13-4 \sqrt{3}+13+4 \sqrt{3}=26 .

\)

Alternatively, using Vieta’s formulas for \(x^2+2 x-11=0\), we have \(x_3+x_4=-2\) and \(x_3 x_4=-11\).

\(

x_3^2+x_4^2=\left(x_3+x_4\right)^2-2 x_3 x_4=(-2)^2-2(-11)=4+22=26 .

\)

Step 3: Find the total sum

The total sum is the sum of the squares of the roots of both equations.

Total Sum = (Sum of squares from first equation) + (Sum of squares from second equation)

Total Sum \(=10+26=36\). -

Question 2 of 101

2. Question

The number of real roots of the equation \(x|x-2|+3|x-3|+1=0\) is : [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 7th April Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(d) Step 1: Analyze the equation by considering cases for the absolute values

The equation is \(x|x-2|+3|x-3|+1=0\). The critical points for the absolute value expressions are \(x=2\) and \(x=3\). We need to consider three cases based on these critical points.

Step 2: Solve the equation for the case \(\boldsymbol{x}<2\)

For \(x<2\), we have \(|x-2|=-(x-2)=2-x\) and \(|x-3|=-(x-3)=3-x\). Substituting these into the equation, we get:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x(2-x)+3(3-x)+1=0 \\

2 x-x^2+9-3 x+1=0 \\

-x^2-x+10=0 \\

x^2+x-10=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Using the quadratic formula, \(x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}\), we find the roots:

\(

x=\frac{-1 \pm \sqrt{1^2-4(1)(-10)}}{2}=\frac{-1 \pm \sqrt{41}}{2}

\)

The two potential roots are \(\frac{-1+\sqrt{41}}{2}\) and \(\frac{-1-\sqrt{41}}{2}\).

Since \(\sqrt{41}\) is approximately \(6.4, \frac{-1+\sqrt{41}}{2} \approx 2.7\), which is not less than 2 .

However, \(\frac{-1-\sqrt{41}}{2} \approx-3.7\), which is less than 2 .

Thus, \(x=\frac{-1-\sqrt{41}}{2}\) is one real root.

Step 3: Solve the equation for the case \(2 \leq x<3\)

For \(2 \leq x<3\), we have \(|x-2|=x-2\) and \(|x-3|=-(x-3)=3-x\). The equation becomes:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x(x-2)+3(3-x)+1=0 \\

x^2-2 x+9-3 x+1=0 \\

x^2-5 x+10=0

\end{gathered}

\)

We check the discriminant, \(\Delta=b^2-4 a c=(-5)^2-4(1)(10)=25-40=-15\). Since the discriminant is negative, this quadratic equation has no real roots.

Step 4: Solve the equation for the case \(\boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{\geq} \mathbf{3}\)

For \(x \geq 3\), we have \(|x-2|=x-2\) and \(|x-3|=x-3\).

The equation becomes:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x(x-2)+3(x-3)+1=0 \\

x^2-2 x+3 x-9+1=0 \\

x^2+x-8=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Using the quadratic formula, we find the roots:

\(

x=\frac{-1 \pm \sqrt{1^2-4(1)(-8)}}{2}=\frac{-1 \pm \sqrt{33}}{2}

\)

The two potential roots are \(\frac{-1+\sqrt{33}}{2}\) and \(\frac{-1-\sqrt{33}}{2}\).

Since \(\sqrt{33}\) is approximately \(5.7, \frac{-1+\sqrt{33}}{2} \approx 2.3\), which is not greater than or equal to 3.

Also, \(\frac{-1-\sqrt{33}}{2} \approx-3.3\), which is not greater than or equal to 3.

Thus, there are no real roots in this case.

By considering all cases, we found only one valid real root. -

Question 3 of 101

3. Question

Let the set of all values of \(p \in \mathbb{R}\), for which both the roots of the equation \(x^2-(p+2) x+(2 p+9)=0\) are negative real numbers, be the interval \((\alpha, \beta]\). Then \(\beta-2 \alpha\) is equal to [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 7th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) Step 1: Conditions for negative real roots

For a quadratic equation \(x^2-(p+2) x+(2 p+9)=0\) to have two negative real roots, three conditions must be met:

1. The discriminant ( \(\boldsymbol{D}\) ) must be non-negative for the roots to be real.

2. The sum of the roots must be negative.

3. The product of the roots must be positive.

Step 2: Applying the conditions

Let the roots be \(x_1\) and \(x_2\).

From the quadratic formula, the sum of the roots is \(x_1+x_2=-\frac{b}{a}=-(-(p+2))=p+2\), and the product of the roots is \(x_1 x_2=\frac{c}{a}=2 p+9\).

Condition 1: Discriminant must be non-negative ( \(\boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{\geq} \mathbf{0}\) )

The discriminant is given by \(D=b^2-4 a c\).

\(

D=(-(p+2))^2-4(1)(2 p+9)=p^2+4 p+4-8 p-36=p^2-4 p-32

\)

We need \(p^2-4 p-32 \geq 0\).

Factoring the quadratic, we get \((p-8)(p+4) \geq 0\).

This inequality holds when \(p \leq-4\) or \(p \geq 8\).

Condition 2: Sum of roots must be negative ( \(x_1+x_2<0\) )

\(

p+2<0

\)

This implies \(p<-2\).

Step 3: Finding the interval for p

We must satisfy all three conditions simultaneously. We need to find the intersection of the intervals from Step 2:

1. \(p \in(-\infty,-4] \cup[8, \infty)\)

2. \(p \in(-\infty,-2)\)

3. \(p \in(-4.5, \infty)\)

The intersection of these three intervals is:

\(

p \in(-4.5,-4]

\)

This is the interval \((\alpha, \beta]\). Comparing the two, we find \(\alpha=-4.5\) and \(\beta=-4\).

The value of \(\beta-2 \alpha\) is:

\(

\beta-2 \alpha=-4-2(-4.5)=-4+9=5

\) -

Question 4 of 101

4. Question

Consider the equation \(x^2+4 x-n=0\), where \(n \in[20,100]\) is a natural number. Then the number of all distinct values of \(n\), for which the given equation has integral roots, is equal to [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 4th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) Here is a step-by-step explanation of the solution presented in the code:

Step 1: Solve for \(\boldsymbol{x}\) using the quadratic formula:

\(

x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}

\)

For the given equation \(x^2+4 x-n=0(a=1, b=4, c=-n)\), the formula yields:

\(

x=\frac{-4 \pm \sqrt{4^2-4(1)(-n)}}{2(1)}=\frac{-4 \pm \sqrt{16+4 n}}{2}=-2 \pm \sqrt{4+n}

\)

Step 2: Condition for integer roots:

For \(x\) to be an integer, the value inside the square root, \(4+n\), must be a perfect square. Let \(4+n=k^2\) for some integer \(k\).

Step 3: Determine the range for \(\boldsymbol{n}+\mathbf{4}\) :

The problem specifies that \(n\) must be in the range [20,100], meaning \(20 \leq n \leq 100\).

Adding 4 to all parts of the inequality gives the range for \(4+n\) :

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 20+4 \leq n+4 \leq 100+4 \\

& 24 \leq n+4 \leq 104

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 4: Identify perfect squares within the range:

We need to find the number of perfect squares \(\left(k^2\right)\) that fall within the interval [24, 104].

1. \(4^2=16\) (too small)

2. \(5^2=25\) (within the range)

3. \(6^2=36\)

4. \(7^2=49\)

5. \(8^2=64\)

6. \(9^2=81\)

7. \(10^2=100\) (within the range)

8. \(11^2=121\) (too large)

The perfect squares are \(\{25,36,49,64,81,100\}\).

Count the values:

There are 6 such perfect squares. Each perfect square corresponds to a unique integer value of \(n\) within the specified range (e.g., \(4+n=25 \Longrightarrow n=21\) ), so there are 6 values of \(n\). -

Question 5 of 101

5. Question

Let the equation \(x(x+2)(12-k)=2\) have equal roots. Then the distance of the point \(\left(k, \frac{k}{2}\right)\) from the line \(3 x+4 y+5=0\) is [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 3rd April Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) Step 1: Find the value of \(\boldsymbol{k}\)

The given equation is \(x(x+2)(12-k)=2\). To find the value of \(k\) for which the equation has equal roots, we first expand and rearrange the equation into a standard quadratic form \(a x^2+b x+c=0\).

\(

\begin{gathered}

\left(x^2+2 x\right)(12-k)=2 \\

(12-k) x^2+2(12-k) x-2=0

\end{gathered}

\)

For a quadratic equation to have equal roots, its discriminant ( \(\Delta\) ) must be zero. The discriminant is given by the formula \(\Delta=b^2-4 a c\). In our equation, \(a=(12-k)\), \(b=2(12-k)\), and \(c=-2\).

\(

\begin{gathered}

(2(12-k))^2-4(12-k)(-2)=0 \\

4(12-k)^2+8(12-k)=0

\end{gathered}

\)

We can factor out \(4(12-k)\) from the expression:

\(

\begin{gathered}

4(12-k)[(12-k)+2]=0 \\

4(12-k)(14-k)=0

\end{gathered}

\)

This gives two possible values for \(k\) : \(k=12\) or \(k=14\).

If \(k=12\), the original equation becomes \((12-12) x^2+2(12-12) x-2=0\), which simplifies to \(-2=0\). This is a contradiction, so \(k \neq 12\).

Therefore, the only valid value for \(\boldsymbol{k}\) is \(\mathbf{1 4}\).

Step 2: Find the distance of the point from the line

The point is given by \(\left(k, \frac{k}{2}\right)\). Using \(k=14\), the coordinates of the point are \(\left(14, \frac{14}{2}\right)=(14,7)\).

The given line is \(3 x+4 y+5=0\).

The distance \(D\) of a point \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)\) from a line \(A x+B y+C=0\) is given by the formula:

\(

D=\frac{\left|A x_1+B y_1+C\right|}{\sqrt{A^2+B^2}}

\)

Here, \(\left(x_1, y_1\right)=(14,7)\) and the line coefficients are \(A=3, B=4\), and \(C=5\). Substituting these values into the formula:

\(

\begin{gathered}

D=\frac{|3(14)+4(7)+5|}{\sqrt{3^2+4^2}} \\

D=\frac{|42+28+5|}{\sqrt{9+16}} \\

D=\frac{|75|}{\sqrt{25}} \\

D=\frac{75}{5} \\

D=15

\end{gathered}

\) -

Question 6 of 101

6. Question

Let \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) be the roots of \(x^2+\sqrt{3} x-16=0\), and \(\gamma\) and \(\delta\) be the roots of \(x^2+3 x-1=0\). If \(P_n=\alpha^n+\beta^n\) and \(Q_n=\gamma^n+\hat{o}^n\), then \(\frac{P_{25}+\sqrt{3} P_{24}}{2 P_{23}}+\frac{Q_{25}-Q_{23}}{Q_{24}}\) is equal to [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 3rd April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(c) Step 1: Analyze the first expression

The first quadratic equation is \(x^2+\sqrt{3} x-16=0\), with roots \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\). Since \(\alpha\) is a root, it satisfies the equation:

\(

\alpha^2+\sqrt{3} \alpha-16=0

\)

Multiplying by \(\alpha^{23}\), we get:

\(

\alpha^{25}+\sqrt{3} \alpha^{24}-16 \alpha^{23}=0

\)

Similarly, for the root \(\beta\) :

\(

\beta^{25}+\sqrt{3} \beta^{24}-16 \beta^{23}=0

\)

Adding these two equations gives:

\(

\left(\alpha^{25}+\beta^{25}\right)+\sqrt{3}\left(\alpha^{24}+\beta^{24}\right)-16\left(\alpha^{23}+\beta^{23}\right)=0

\)

Using the definition \(P_n=\alpha^n+\beta^n\), this can be written as:

\(

P_{25}+\sqrt{3} P_{24}-16 P_{23}=0

\)

Rearranging the terms, we find:

\(

P_{25}+\sqrt{3} P_{24}=16 P_{23}

\)

Substituting this into the first part of the original expression:

\(

\frac{P_{25}+\sqrt{3} P_{24}}{2 P_{23}}=\frac{16 P_{23}}{2 P_{23}}=\frac{16}{2}=8

\)

Step 2: Analyze the second expression

The second quadratic equation is \(x^2+3 x-1=0\), with roots \(\gamma\) and \(\delta\). Since \(\gamma\) is a root, it satisfies the equation:

\(

\gamma^2+3 \gamma-1=0

\)

Multiplying by \(\gamma^{23}\), we get:

\(

\gamma^{25}+3 \gamma^{24}-\gamma^{23}=0

\)

Similarly, for the root \(\delta\) :

\(

\delta^{25}+3 \delta^{24}-\delta^{23}=0

\)

Adding these two equations gives:

\(

\left(\gamma^{25}+\delta^{25}\right)+3\left(\gamma^{24}+\delta^{24}\right)-\left(\gamma^{23}+\delta^{23}\right)=0

\)

Using the definition \(Q_n=\gamma^n+\delta^n\), this can be written as:

\(

Q_{25}+3 Q_{24}-Q_{23}=0

\)

Rearranging the terms, we get:

\(

Q_{25}-Q_{23}=-3 Q_{24}

\)

Substituting this into the second part of the original expression:

\(

\frac{Q_{25}-Q_{23}}{Q_{24}}=\frac{-3 Q_{24}}{Q_{24}}=-3

\)

The value of the expression is the sum of the results from the two parts:

\(

\frac{P_{25}+\sqrt{3} P_{24}}{2 P_{23}}+\frac{Q_{25}-Q_{23}}{Q_{24}}=8+(-3)=5

\) -

Question 7 of 101

7. Question

Let \(\mathrm{P}_{\mathrm{n}}=\alpha^{\mathrm{n}}+\beta^{\mathrm{n}}, \mathrm{n} \in \mathrm{N}\). If \(\mathrm{P}_{10}=123, \mathrm{P}_9=76, \mathrm{P}_8=47\) and \(\mathrm{P}_1=1\), then the quadratic equation having roots \(\frac{1}{\alpha}\) and \(\frac{1}{\beta}\) is : [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 2nd April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) The quadratic equation with roots \(r_1\) and \(r_2\) is given by \(x^2-\left(r_1+r_2\right) x+r_1 r_2=0\)

Step 1: Find the sum and product of the roots of the new quadratic equation

The roots of the required quadratic equation are \(\frac{1}{\alpha}\) and \(\frac{1}{\beta}\).

The sum of the roots is \(\frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\beta}=\frac{\alpha+\beta}{\alpha \beta}\).

The product of the roots is \(\frac{1}{\alpha} \cdot \frac{1}{\beta}=\frac{1}{\alpha \beta}\).

The required equation is \(x^2-\left(\frac{\alpha+\beta}{\alpha \beta}\right) x+\left(\frac{1}{\alpha \beta}\right)=0\).

Step 2: Use the given information to find \(\alpha+\beta\) and \(\alpha \beta\)

We are given \(P_n=\alpha^n+\beta^n\).

For \(n=1, P_1=\alpha^1+\beta^1=\alpha+\beta\).

We are given \(P_1=1\), so \(\alpha+\beta=1\).

We can use the recurrence relation for \(\boldsymbol{P}_{\boldsymbol{n}}\). The quadratic equation with roots \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) is \(x^2-(\alpha+\beta) x+\alpha \beta=0\). This leads to the recurrence relation

\(

P_n=(\alpha+\beta) P_{n-1}-(\alpha \beta) P_{n-2} .

\)

We have \(P_{10}=(\alpha+\beta) P_9-(\alpha \beta) P_8\).

Using the given values \(P_{10}=123, P_9=76\), and \(P_8=47\) :

\(

123=(\alpha+\beta)(76)-(\alpha \beta)(47)

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Since we already found } \alpha+\beta=1 \text { : }\\

&\begin{gathered}

123=(1)(76)-47(\alpha \beta) \\

123=76-47(\alpha \beta) \\

123-76=-47(\alpha \beta) \\

47=-47(\alpha \beta) \\

\alpha \beta=-1

\end{gathered}

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 3: Substitute the values into the equation from Step 1

Now we have the values for \(\alpha+\beta=1\) and \(\alpha \beta=-1\).

Sum of roots: \(\frac{\alpha+\beta}{\alpha \beta}=\frac{1}{-1}=-1\).

Product of roots: \(\frac{1}{\alpha \beta}=\frac{1}{-1}=-1\).

Substituting these into the quadratic equation:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x^2-(-1) x+(-1)=0 \\

x^2+x-1=0

\end{gathered}

\)

The quadratic equation having roots \(\frac{1}{\alpha}\) and \(\frac{1}{\beta}\) is \(x^2+x-1=0\). -

Question 8 of 101

8. Question

If the set of all \(a \in \mathbf{R}\), for which the equation \(2 x^2+(a-5) x+15=3 a\) has no real root, is the interval \((\alpha, \beta)\), and \(X=|x \in Z ; \alpha<x<\beta|\), then \(\sum_{x \in X} x^2\) is equal to: [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 29th January Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) Step 1: Find the interval ( \(\alpha, \beta\) ) for ‘ \(a\) ‘

The given equation is \(2 x^2+(a-5) x+15=3 a\). To have no real roots, the discriminant of the quadratic equation must be less than zero. First, we rewrite the equation in the standard form \(\boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{x}^2+\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{x}+\boldsymbol{C}=\mathbf{0}\) :

\(

2 x^2+(a-5) x+(15-3 a)=0

\)

The discriminant, \(\Delta\), is given by \(\Delta=B^2-4 A C\). Here, \(A=2, B=a-5\), and \(C=15-3 a\).

We set up the inequality \(\Delta<0\) :

\(

(a-5)^2-4(2)(15-3 a)<0

\)

Expand and simplify the inequality:

\(

\begin{gathered}

a^2-10 a+25-8(15-3 a)<0 \\

a^2-10 a+25-120+24 a<0 \\

a^2+14 a-95<0

\end{gathered}

\)

To find the values of ‘ \(a\) ‘ that satisfy this inequality, we first find the roots of the equation \(a^2+14 a-95=0\). We can factor this as \((a+19)(a-5)=0\), which gives us the roots \(a=-19\) and \(a=5\). Since the parabola \(y=a^2+14 a-95\) opens upwards, the inequality is satisfied between the roots.

Thus, the interval for ‘ \(a\) ‘ is \((-19,5)\).

So, \(\alpha=-19\) and \(\beta=5\).

Step 2: Determine the set X

The set \(X\) is defined as \(X=|x \in Z ; \alpha<x<\beta|\), where \(\alpha=-19\) and \(\beta=5\). This means \(X\) is the set of all integers \(x\) such that \(-19<x<5\). The integers in this range are \(-18,-17,-16, \ldots, 3,4\)

Step 3: Calculate the sum of squares, \(\sum_{x \in X} x^2\)

We need to calculate \(\sum_{x=-18}^4 x^2=(-18)^2+(-17)^2+\ldots+3^2+4^2\).

We can rewrite this sum as:

\(

\sum_{x=1}^{18} x^2-\sum_{x=5}^{18} x^2+\sum_{x=1}^4 x^2

\)

Which simplifies to:

\(

\sum_{x=-18}^{-1} x^2+\sum_{x=0}^4 x^2=\sum_{y=1}^{18} y^2+\sum_{x=1}^4 x^2

\)

We use the formula for the sum of the first \(n\) squares: \(\sum_{i=1}^n i^2=\frac{n(n+1)(2 n+1)}{6}\).

For the first sum, \(n=18\) :

\(

\sum_{y=1}^{18} y^2=\frac{18(18+1)(2(18)+1)}{6}=\frac{18(19)(37)}{6}=3(19)(37)=2109

\)

For the second sum, \(n=4\) :

\(

\sum_{x=1}^4 x^2=\frac{4(4+1)(2(4)+1)}{6}=\frac{4(5)(9)}{6}=2(5)(3)=30

\)

The total sum is the sum of these two results:

\(

2109+30=2139

\) -

Question 9 of 101

9. Question

The number of solutions of the equation \(\left(\frac{9}{x}-\frac{9}{\sqrt{x}}+2\right)\left(\frac{2}{x}-\frac{7}{\sqrt{x}}+3\right)=0\) is : [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 29th January Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(d) The question asks for the number of solutions to the equation \(\left(\frac{9}{x}-\frac{9}{\sqrt{x}}+2\right)\left(\frac{2}{x}-\frac{7}{\sqrt{x}}+3\right)=0\). This equation holds true if either of the two factors equals zero. Let’s solve each factor separately.

Step 1: Solve the first factor

Set the first factor equal to zero:

\(

\frac{9}{x}-\frac{9}{\sqrt{x}}+2=0

\)

To simplify this, let’s introduce a substitution. Let \(y=\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}\). Then \(y^2=\frac{1}{x}\). Substituting these into the equation, we get a quadratic equation in terms of \(y\) :

\(

9 y^2-9 y+2=0

\)

We can solve for \(y\) using the quadratic formula, \(y=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}\) :

\(

y=\frac{-(-9) \pm \sqrt{(-9)^2-4(9)(2)}}{2(9)}=\frac{9 \pm \sqrt{81-72}}{18}=\frac{9 \pm \sqrt{9}}{18}=\frac{9 \pm 3}{18}

\)

This gives us two possible values for \(y\) :

\(

\begin{aligned}

& y_1=\frac{9+3}{18}=\frac{12}{18}=\frac{2}{3} \\

& y_2=\frac{9-3}{18}=\frac{6}{18}=\frac{1}{3}

\end{aligned}

\)

Now, we substitute back \(y=\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}\) to find the values of \(x\) :

For \(y_1=\frac{2}{3}\) :

\(

\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}=\frac{2}{3} \Longrightarrow \sqrt{x}=\frac{3}{2} \Longrightarrow x=\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^2=\frac{9}{4}

\)

For \(y_2=\frac{1}{3}\) :

\(

\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}=\frac{1}{3} \Longrightarrow \sqrt{x}=3 \Longrightarrow x=3^2=9

\)

Both \(x=\frac{9}{4}\) and \(x=9\) are valid solutions since they are positive, which is required for the \(\sqrt{x}\) term.

Step 2: Solve the second factor

Set the second factor equal to zero:

\(

\frac{2}{x}-\frac{7}{\sqrt{x}}+3=0

\)

Using the same substitution, \(y=\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}\) and \(y^2=\frac{1}{x}\), we get a new quadratic equation:

\(

2 y^2-7 y+3=0

\)

Using the quadratic formula:

\(

y=\frac{-(-7) \pm \sqrt{(-7)^2-4(2)(3)}}{2(2)}=\frac{7 \pm \sqrt{49-24}}{4}=\frac{7 \pm \sqrt{25}}{4}=\frac{7 \pm 5}{4}

\)

This also gives us two possible values for \(y\) :

\(

\begin{aligned}

& y_3=\frac{7+5}{4}=\frac{12}{4}=3 \\

& y_4=\frac{7-5}{4}=\frac{2}{4}=\frac{1}{2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Substituting back \(y=\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}\) to find the values of \(x\) :

For \(y_3=3\) :

\(

\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}=3 \Longrightarrow \sqrt{x}=\frac{1}{3} \Longrightarrow x=\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^2=\frac{1}{9}

\)

For \(y_4=\frac{1}{2}\) :

\(

\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}=\frac{1}{2} \Longrightarrow \sqrt{x}=2 \Longrightarrow x=2^2=4

\)

Both \(x=\frac{1}{9}\) and \(x=4\) are valid solutions.

Step 3: Count the unique solutions

The solutions found are \(x=\frac{9}{4}, x=9, x=\frac{1}{9}\), and \(x=4\). All four of these values are unique and positive, satisfying the domain of the original equation.

The number of solutions of the equation is \(\mathbf{4}\). -

Question 10 of 101

10. Question

Let \(f: \mathbf{R}-\{0\} \rightarrow(-\infty, 1)\) be a polynomial of degree 2 , satisfying \(f(x) f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)=f(x)+f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\). If \(f(\mathrm{~K})=-2 \mathrm{~K}\), then the sum of squares of all possible values of \(K\) is : [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 28th January Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(c) Step 1: Determine the form of the polynomial \(\boldsymbol{f}(\boldsymbol{x})\)

The given functional equation is \(f(x) f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)=f(x)+f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\).

This can be rearranged by subtracting \(f(x)\) and \(f(1 / x)\) from both sides:

\(

f(x) f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)-f(x)-f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)=0

\)

Adding 1 to both sides allows us to factor the expression:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& f(x) f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)-f(x)-f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)+1=1 \\

& (f(x)-1)\left(f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)-1\right)=1

\end{aligned}

\)

Since \(f(x)\) is a polynomial of degree 2 , let \(f(x)=a x^2+b x+c\).

Substitute this into the factored equation:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \left(\left(a x^2+b x+c\right)-1\right)\left(a\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)^2+b\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)+c-1\right)=1 \\

& \left(a x^2+b x+c-1\right)\left(\frac{a}{x^2}+\frac{b}{x}+c-1\right)=1 \\

& \left(a x^2+b x+c-1\right)\left(\frac{a+b x+(c-1) x^2}{x^2}\right)=1 \\

& \left(a x^2+b x+c-1\right)\left(a+b x+(c-1) x^2\right)=x^2

\end{aligned}

\)

The coefficients of the resulting polynomial must match the coefficients of \(x^2\). By comparing coefficients, we get:

Coefficient of \(x^4: a(c-1)=0\). Since \(f(x)\) is a degree 2 polynomial, \(a \neq 0\). Thus, \(c-1=0 \Longrightarrow c=1\).

Coefficient of \(x^3: a(b)+b(c-1)=0 \Longrightarrow a b=0\). Since \(a \neq 0\), we have \(b=0\).

Coefficient of \(x^2\) :

\(

a(a)+b(b)+(c-1)(c-1)=1 \Longrightarrow a^2+(1-1)^2=1 \Longrightarrow a^2=1 \Longrightarrow a= \pm 1 .

\)

Coefficient of \(x: b(a)+b(c-1)=0 \Longrightarrow 0=0\).

Constant term: \((c-1) a=0 \Longrightarrow 0=0\).

So, the coefficients are \(b=0\) and \(c=1\), and \(a=1\) or \(a=-1\).

The polynomial is \(f(x)=a x^2+1\).

The problem states that the range of \(f\) is \((-\infty, 1)\). A parabola with a maximum value less than 1 must open downwards. This means the leading coefficient, \(a\), must be negative. Therefore, \(a=-1\).

So, \(f(x)=-x^2+1\).

Step 2: Solve for \(K\) and find the sum of squares

The problem gives the condition \(f(K)=-2 K\). Substitute the form of \(f(x)\) we found:

\(

-K^2+1=-2 K

\)

Rearrange the equation to a standard quadratic form:

\(

K^2-2 K-1=0

\)

The possible values of \(\boldsymbol{K}\) are the roots of this quadratic equation. Let the roots be \(\boldsymbol{K}_1\) and \(K_2\).

By the properties of quadratic equations, for \(a x^2+b x+c=0\), the sum of the roots is \(K_1+K_2=-b / a\) and the product of the roots is \(K_1 K_2=c / a\).

For our equation, \(K^2-2 K-1=0\), we have \(a=1, b=-2, c=-1\).

\(

\begin{gathered}

K_1+K_2=-(-2) / 1=2 \\

K_1 K_2=-1 / 1=-1

\end{gathered}

\)

We need to find the sum of the squares of all possible values of \(\boldsymbol{K}\), which is \(\boldsymbol{K}_1^2+\boldsymbol{K}_2^2\). This can be expressed using the sum and product of the roots:

\(

K_1^2+K_2^2=\left(K_1+K_2\right)^2-2 K_1 K_2

\)

Substitute the values we found:

\(

\begin{gathered}

K_1^2+K_2^2=(2)^2-2(-1) \\

K_1^2+K_2^2=4+2=6

\end{gathered}

\)

The sum of squares of all possible values of \(K\) is 6. -

Question 11 of 101

11. Question

The sum, of the squares of all the roots of the equation \(x^2+|2 x-3|-4=0\), is [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 28th January Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) Step 1: Solve the equation by considering the absolute value

The equation is \(x^2+|2 x-3|-4=0\). To solve this, we need to consider two cases based on the expression inside the absolute value.

Case 1: \(2 x-3 \geq 0\), which means \(x \geq \frac{3}{2}\).

In this case, \(|2 x-3|=2 x-3\). The equation becomes:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x^2+(2 x-3)-4=0 \\

x^2+2 x-7=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Using the quadratic formula, \(x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}\), we find the roots:

\(

x=\frac{-2 \pm \sqrt{2^2-4(1)(-7)}}{2(1)}=\frac{-2 \pm \sqrt{4+28}}{2}=\frac{-2 \pm \sqrt{32}}{2}=\frac{-2 \pm 4 \sqrt{2}}{2}=-1 \pm 2 \sqrt{2}

\)

We must check if these roots satisfy the condition \(x \geq \frac{3}{2}\).

For \(x=-1+2 \sqrt{2} \approx-1+2(1.414)=1.828\), this root satisfies the condition.

For \(x=-1-2 \sqrt{2} \approx-1-2(1.414)=-3.828\), this root does not satisfy the condition.

So, from this case, we have one root: \(r_1=-1+2 \sqrt{2}\).

Case 2: \(2 x-3<0\), which means \(x<\frac{3}{2}\).

In this case, \(|2 x-3|=-(2 x-3)=3-2 x\). The equation becomes:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x^2+(3-2 x)-4=0 \\

x^2-2 x-1=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Using the quadratic formula:

\(

x=\frac{-(-2) \pm \sqrt{(-2)^2-4(1)(-1)}}{2(1)}=\frac{2 \pm \sqrt{4+4}}{2}=\frac{2 \pm \sqrt{8}}{2}=\frac{2 \pm 2 \sqrt{2}}{2}=1 \pm \sqrt{2}

\)

We must check if these roots satisfy the condition \(x<\frac{3}{2}\).

For \(x=1+\sqrt{2} \approx 1+1.414=2.414\), this root does not satisfy the condition.

For \(x=1-\sqrt{2} \approx 1-1.414=-0.414\), this root satisfies the condition.

So, from this case, we have one root: \(r_2=1-\sqrt{2}\).

The roots of the original equation are \(r_1=-1+2 \sqrt{2}\) and \(r_2=1-\sqrt{2}\).

Step 2: Calculate the sum of the squares of the roots

The sum of the squares of the roots is \(r_1^2+r_2^2\).

\(

\begin{gathered}

r_1^2=(-1+2 \sqrt{2})^2=(-1)^2+2(-1)(2 \sqrt{2})+(2 \sqrt{2})^2=1-4 \sqrt{2}+8=9-4 \sqrt{2} \\

r_2^2=(1-\sqrt{2})^2=(1)^2-2(1)(\sqrt{2})+(\sqrt{2})^2=1-2 \sqrt{2}+2=3-2 \sqrt{2}

\end{gathered}

\)

The sum is:

\(

r_1^2+r_2^2=(9-4 \sqrt{2})+(3-2 \sqrt{2})=12-6 \sqrt{2}=6(2-\sqrt{2})

\)

The sum of the squares of all the roots of the equation is \(6(2-\sqrt{2})\). -

Question 12 of 101

12. Question

The number of real solution(s) of the equation \(x^2+3 x+2=\min \{|x-3|,|x+2|\}\) is : [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 24th January Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) The equation is \(x^2+3 x+2=\min \{|x-3|,|x+2|\}\).

The expression \(|x-3|\) represents the distance from \(x\) to 3 , and \(|x+2|\) represents the distance from \(x\) to -2. The minimum of the two is determined by which reference point \(x\) is closer to. The midpoint between -2 and 3 is \((-2+3) / 2=0.5\).

For \(x \leq 0.5,|x-3| \geq|x+2|\), so \(\min \{|x-3|,|x+2|\}=|x+2|\).

For \(x>0.5,|x-3|<|x+2|\), so \(\min \{|x-3|,|x+2|\}=|x-3|\).

We consider the two cases:

Case 1: \(x \leq 0.5\)

The equation becomes \(x^2+3 x+2=|x+2|\). This further splits into two sub-cases based on the sign of \(x+2\) :

If \(-2 \leq x \leq 0.5\), then \(x+2 \geq 0\), so the equation is \(x^2+3 x+2=x+2\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2+2 x=0 \\

& x(x+2)=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Solutions are \(x=0\) and \(x=-2\). Both are in the valid range \([-2,0.5]\), so they are valid solutions.

If \(x<-2\), then \(x+2<0\), so the equation is \(x^2+3 x+2=-(x+2)\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2+3 x+2=-x-2 \\

& x^2+4 x+4=0 \\

& (x+2)^2=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Solution is \(x=-2\). This solution is not in the range \(x<-2\), but at the boundary. It is consistent with the other sub-case’s result.

Case 2: \(x>0.5\)

The equation becomes \(x^2+3 x+2=|x-3|\). This further splits into two sub-cases based on the sign of \(x-3\) :

If \(0.5<x \leq 3\), then \(x-3 \leq 0\), so the equation is \(x^2+3 x+2=-(x-3)\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

& x^2+3 x+2=-x+3 \\

& x^2+4 x-1=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Using the quadratic formula,

\(

x=\frac{-4 \pm \sqrt{4^2-4(1)(-1)}}{2}=\frac{-4 \pm \sqrt{20}}{2}=-2 \pm \sqrt{5} .

\)

\(\sqrt{5} \approx 2.236\). The solutions are \(x \approx-4.236\) and \(x \approx 0.236\). Neither solution is in the valid range ( \(0.5,3\) ].

If \(x>3\), then \(x-3>0\), so the equation is \(x^2+3 x+2=x-3\).

\(

x^2+2 x+5=0

\)

The discriminant is \(2^2-4(1)(5)=4-20=-16<0\). There are no real solutions in this sub-case.

The real solutions found are \(x=0\) and \(x=-2\). Thus, there are 2 real solutions. -

Question 13 of 101

13. Question

The product of all the rational roots of the equation \(\left(x^2-9 x+11\right)^2-(x-4)(x-5)=3\), is equal to [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 24th January Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(d) Step 1: Simplify the equation

The given equation is \(\left(x^2-9 x+11\right)^2-(x-4)(x-5)=3\).

First, expand the second term:

\(

(x-4)(x-5)=x^2-5 x-4 x+20=x^2-9 x+20

\)

The equation can be rewritten as:

\(

\left(x^2-9 x+11\right)^2-\left(x^2-9 x+20\right)=3

\)

To simplify, let \(y=x^2-9 x\). The equation becomes:

\(

(y+11)^2-(y+20)=3

\)

Expand and simplify this quadratic in \(y\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

y^2+22 y+121-y-20=3 \\

y^2+21 y+101=3 \\

y^2+21 y+98=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 2: Solve for the values of \(\boldsymbol{x}\)

Factor the quadratic equation for \(y\) :

\(

(y+7)(y+14)=0

\)

This gives two possible values for \(y: y_1=-7\) and \(y_2=-14\).

Now, substitute back \(y=x^2-9 x\) and solve for \(x\) in each case.

Case 1: \(y=-7\)

\(

\begin{gathered}

x^2-9 x=-7 \\

x^2-9 x+7=0

\end{gathered}

\)

The discriminant is \(\Delta=(-9)^2-4(1)(7)=81-28=53\).

Since the discriminant is not a perfect square, the roots are irrational: \(x=\frac{9 \pm \sqrt{53}}{2}\)

Case 2: \(y=-14\)

\(

\begin{gathered}

x^2-9 x=-14 \\

x^2-9 x+14=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Factor this quadratic equation:

\(

(x-2)(x-7)=0

\)

The roots are \(x=2\) and \(x=7\). Both of these roots are rational.

The rational roots of the equation are 2 and 7. The product of all the rational roots is:

\(

2 \times 7=14

\) -

Question 14 of 101

14. Question

Let \(\alpha_\theta\) and \(\beta_\theta\) be the distinct roots of \(2 x^2+(\cos \theta) x-1=0, \theta \in(0,2 \pi)\). If m and M are the minimum and the maximum values of \(\alpha_\theta^4+\beta_\theta^4\), then \(16(M+m)\) equals : [JEE Main 2025 (Online) 22nd January Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(c) Step 1: Express \(\alpha_\theta^4+\beta_\theta^4\) in terms of \(\cos \theta\)

Given the quadratic equation \(2 x^2+(\cos \theta) x-1=0\), let the roots be \(\alpha_\theta\) and \(\beta_\theta\).

Using Vieta’s formulas, the sum and product of the roots are:

Sum of roots: \(\alpha_\theta+\beta_\theta=-\frac{\cos \theta}{2}\)

Product of roots: \(\alpha_\theta \beta_\theta=-\frac{1}{2}\)

We can express \(\alpha_\theta^4+\beta_\theta^4\) in terms of the sum and product of the roots.

First, find \(\alpha_\theta^2+\beta_\theta^2\) :

\(

\alpha_\theta^2+\beta_\theta^2=\left(\alpha_\theta+\beta_\theta\right)^2-2 \alpha_\theta \beta_\theta=\left(-\frac{\cos \theta}{2}\right)^2-2\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)=\frac{\cos ^2 \theta}{4}+1

\)

Next, find \(\alpha_\theta^4+\beta_\theta^4\) :

\(

\alpha_\theta^4+\beta_\theta^4=\left(\alpha_\theta^2+\beta_\theta^2\right)^2-2\left(\alpha_\theta \beta_\theta\right)^2=\left(\frac{\cos ^2 \theta}{4}+1\right)^2-2\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)^2=\left(\frac{\cos ^2 \theta}{4}+1\right)^2-2\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\alpha_\theta^4+\beta_\theta^4=\left(\frac{\cos ^2 \theta}{4}\right)^2+2\left(\frac{\cos ^2 \theta}{4}\right)(1)+1^2-\frac{1}{2}=\frac{\cos ^4 \theta}{16}+\frac{\cos ^2 \theta}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\\

&\text { Let } f(\theta)=\alpha_\theta^4+\beta_\theta^4=\frac{1}{16} \cos ^4 \theta+\frac{1}{2} \cos ^2 \theta+\frac{1}{2} .

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 2: Find the minimum ( \(m\) ) and maximum ( \(M\) ) values

To find the minimum and maximum values of \(f(\theta)\), we can analyze the range of the term \(\cos \theta\).

For \(\theta \in(0,2 \pi)\), the range of \(\cos \theta\) is \([-1,1]\).

Let \(u=\cos ^2 \theta\). Then the range of \(u\) is \([0,1]\).

The function becomes \(g(u)=\frac{1}{16} u^2+\frac{1}{2} u+\frac{1}{2}\), where \(u \in[0,1]\).

This is a parabola that opens upwards. The minimum and maximum values on the interval \([0,1]\) will occur at the endpoints.

The vertex of the parabola \(g(u)\) is at \(u=-\frac{b}{2 a}=-\frac{1 / 2}{2(1 / 16)}=-\frac{1 / 2}{1 / 8}=-4\). Since this is outside the interval \([0,1]\), the function is monotonic on the interval.

Minimum value ( \(m\) ):

The minimum value occurs at \(u=0\) (which corresponds to \(\cos \theta=0\) ).

\(

m=g(0)=\frac{1}{16}(0)^2+\frac{1}{2}(0)+\frac{1}{2}=\frac{1}{2}

\)

Maximum value ( \(M\) ):

The maximum value occurs at \(u=1\) (which corresponds to \(\cos \theta= \pm 1\) ).

\(

M=g(1)=\frac{1}{16}(1)^2+\frac{1}{2}(1)+\frac{1}{2}=\frac{1}{16}+1=\frac{17}{16}

\)

Step 3: Calculate \(16(M+m)\)

We have \(M=\frac{17}{16}\) and \(m=\frac{1}{2}\).

\(

M+m=\frac{17}{16}+\frac{1}{2}=\frac{17}{16}+\frac{8}{16}=\frac{25}{16}

\)

Now, multiply by 16 :

\(

16(M+m)=16\left(\frac{25}{16}\right)=25

\) -

Question 15 of 101

15. Question

Let \(\alpha, \beta ; \alpha>\beta\), be the roots of the equation \(x^2-\sqrt{2} x-\sqrt{3}=0\). Let \(\mathrm{P}_n=\alpha^n-\beta^n, n \in \mathrm{~N}\). Then \((11 \sqrt{3}-10 \sqrt{2}) \mathrm{P}_{10}+(11 \sqrt{2}+10) \mathrm{P}_{11}-11 \mathrm{P}_{12}\) is equal to [JEE Main 2024 (Online) 9th April Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) The roots \(\alpha, \beta\) of the equation \(x^2-\sqrt{2} x-\sqrt{3}=0\) satisfy the recurrence relation \(P_n=\sqrt{2} P_{n-1}+\sqrt{3} P_{n-2}\) for \(n \geq 2\), where \(P_n=\alpha^n-\beta^n\).

Thus, \(P_{12}=\sqrt{2} P_{11}+\sqrt{3} P_{10}\), which can be rearranged as \(\sqrt{3} P_{10}=P_{12}-\sqrt{2} P_{11}\).

Also, \(\boldsymbol{P}_{11}=\sqrt{2} \boldsymbol{P}_{10}+\sqrt{3} \boldsymbol{P}_9\), so \(\sqrt{3} \boldsymbol{P}_9=\boldsymbol{P}_{11}-\sqrt{2} \boldsymbol{P}_{10}\).

The given expression is:

\(

\begin{gathered}

E=(11 \sqrt{3}-10 \sqrt{2}) P_{10}+(11 \sqrt{2}+10) P_{11}-11 P_{12} \\

E=11 \sqrt{3} P_{10}-10 \sqrt{2} P_{10}+11 \sqrt{2} P_{11}+10 P_{11}-11 P_{12} \\

E=11\left(\sqrt{3} P_{10}+\sqrt{2} P_{11}-P_{12}\right)+10\left(P_{11}-\sqrt{2} P_{10}\right)

\end{gathered}

\)

From the recurrence relation:

\(

\begin{gathered}

\sqrt{3} P_{10}=P_{12}-\sqrt{2} P_{11} \Longrightarrow \sqrt{3} P_{10}+\sqrt{2} P_{11}-P_{12}=0 \\

P_{11}-\sqrt{2} P_{10}=\sqrt{3} P_9

\end{gathered}

\)

Substituting these into the expression for \(E\) :

\(

\begin{gathered}

E=11(0)+10\left(\sqrt{3} P_9\right) \\

E=10 \sqrt{3} P_9

\end{gathered}

\)

The expression is equal to \(10 \sqrt{3} \boldsymbol{P}_9\). -

Question 16 of 101

16. Question

Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the roots of the equation \(x^2+2 \sqrt{2} x-1=0\). The quadratic equation, whose roots are \(\alpha^4+\beta^4\) and \(\frac{1}{10}\left(\alpha^6+\beta^6\right)\), is: [JEE Main 2024 (Online) 9th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(b)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{aligned}

& x^2+2 \sqrt{2 x}-1=0 \\

& \alpha+\beta=-2 \sqrt{2} \text { and } \alpha \beta=-1 \\

& \alpha^2+\beta^2=(\alpha+\beta)^2-2 \alpha \beta \\

& =8+2=10 \\

& \alpha^4+\beta^4=\left(\alpha^2+\beta^2\right)^2-2(\alpha \beta)^2 \\

& =100-2=98 \\

& \alpha^6+\beta^6=\left(\alpha^2+\beta^2\right)^3-3 \alpha^2 \beta^2\left(\alpha^2+\beta^2\right) \\

& =1000-3(10) \\

& =970 \\

& \therefore \quad \frac{1}{10}\left(\alpha^6+\beta^6\right)=97

\end{aligned}\\

&\text { Equation whose roots are } \alpha^4+\beta^4 \text { and } \frac{1}{10}\left(\alpha^6+\beta^6\right) \text { is }\\

&\begin{aligned}

& x^2-(98+97) x+98 \times 97=0 \\

& x^2-195 x+9506=0

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\) -

Question 17 of 101

17. Question

The sum of all the solutions of the equation \((8)^{2 x}-16 \cdot(8)^x+48=0\) is : [JEE Main 2024 (Online) 8th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) Step 1: Rewrite the equation

The given equation is \((8)^{2 x}-16 \cdot(8)^x+48=0\).

We can rewrite this by substituting a new variable to form a quadratic equation. Let \(y=8^x\).

The equation then becomes:

\(

y^2-16 y+48=0

\)

Step 2: Solve the quadratic equation

We can solve this quadratic equation for \(y\) by factoring. We need two numbers that multiply to 48 and add up to -16. These numbers are -4 and -12.

\(

(y-4)(y-12)=0

\)

This gives us two possible values for \(y\) :

\(

y=4 \text { or } y=12

\)

Step 3: Solve for \(\mathbf{x}\)

Now we substitute back \(y=8^x\) and solve for \(x\) for each value of \(y\).

Case 1: \(y=4\)

\(

8^x=4

\)

To solve for \(\boldsymbol{x}\), we can express both sides as powers of 2.

\(

\begin{gathered}

\left(2^3\right)^x=2^2 \\

2^{3 x}=2^2

\end{gathered}

\)

Equating the exponents, we get:

\(

3 x=2 \Longrightarrow x=\frac{2}{3}

\)

Case 2: \(y=12\)

\(

8^x=12

\)

To solve for \(x\), we take the logarithm of both sides. Using the base- 8 logarithm is convenient.

\(

\begin{gathered}

\log _8\left(8^x\right)=\log _8(12) \\

x=\log _8(12)

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 4: Find the sum of the solutions

The two solutions for \(x\) are \(\frac{2}{3}\) and \(\log _8(12)\).

The sum of the solutions is:

\(

S=\frac{2}{3}+\log _8(12)

\)

We can simplify this expression. We know that \(8^{2 / 3}=\left(8^{1 / 3}\right)^2=2^2=4\). So, \(\frac{2}{3}=\log _8(4)\).

\(

S=\log _8(4)+\log _8(12)

\)

Using the logarithm property \(\log _a(m)+\log _a(n)=\log _a(m n)\) :

\(

S=\log _8(4 \cdot 12)=\log _8(48)

\)

However, the options provided are in a different form. Let’s re-examine the solutions. The solutions are \(x_1=\log _8(4)\) and \(x_2=\log _8(12)\).

Sum of solutions \(x_1+x_2=\log _8(4)+\log _8(12)=\log _8(4 \cdot 12)=\log _8(48)\).

Let’s see if we can manipulate this to match one of the options.

\(

\log _8(48)=\log _8(8 \cdot 6)=\log _8(8)+\log _8(6)=1+\log _8(6)

\)

The sum of all the solutions is \(1+\log _8(6)\). -

Question 18 of 101

18. Question

Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the distinct roots of the equation \(x^2-\left(t^2-5 t+6\right) x+1=0, t \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(a_n=\alpha^n+\beta^n\). Then the minimum value of \(\frac{a_{2023}+a_{2025}}{a_{2024}}\) is [JEE Main 2024 (Online) 6th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(b) Step 1: Complete the Square

The quadratic expression is \(t^2-5 t+6\). To complete the square, take half of the coefficient of \(t\), square it, and add and subtract it from the expression. The coefficient of \(t\) is -5, so half of it is \(-\frac{5}{2}\), and squaring it gives \(\left(-\frac{5}{2}\right)^2=\frac{25}{4}\).

\(

t^2-5 t+\frac{25}{4}-\frac{25}{4}+6

\)

Group the first three terms to form a perfect square trinomial and simplify the constants.

\(

\begin{gathered}

\left(t-\frac{5}{2}\right)^2-\frac{25}{4}+\frac{24}{4} \\

\left(t-\frac{5}{2}\right)^2-\frac{1}{4}

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 2: Determine the Minimum Value

The term \(\left(t-\frac{5}{2}\right)^2\) is a squared term, so its minimum possible value is 0. This occurs when \(t=\frac{5}{2}\). Therefore, the minimum value of the entire expression is when \(\left(t-\frac{5}{2}\right)^2\) is at its minimum.

The minimum value is \(0-\frac{1}{4}=-\frac{1}{4}\). -

Question 19 of 101

19. Question

If 2 and 6 are the roots of the equation \(a x^2+b x+1=0\), then the quadratic equation, whose roots are \(\frac{1}{2 a+b}\) and \(\frac{1}{6 a+b}\), is : [JEE Main 2024 (Online) 4th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) Step 1: Determine the values of a and b

From Vieta’s formulas, for a quadratic equation \(a x^2+b x+c=0\) with roots \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) :

Sum of roots: \(\alpha+\beta=-\frac{b}{a}\)

Product of roots: \(\alpha \beta=\frac{c}{a}\)

For the given equation \(a x^2+b x+1=0\) and roots 2 and 6 :

The sum of the roots is \(2+6=8\).

So, \(8=-\frac{b}{a}\), which means \(b=-8 a\).

The product of the roots is \(2 \times 6=12\).

So, \(12=\frac{1}{a}\), which means \(a=\frac{1}{12}\).

Substitute the value of \(a\) back into the equation for \(b\) :

\(

b=-8 a=-8\left(\frac{1}{12}\right)=-\frac{8}{12}=-\frac{2}{3}

\)

Step 2: Find the new roots

The new roots are \(\frac{1}{2 a+b}\) and \(\frac{1}{6 a+b}\).

Substitute the values of \(a=\frac{1}{12}\) and \(b=-\frac{2}{3}\) :

First new root:

\(

\alpha^{\prime}=\frac{1}{2 a+b}=\frac{1}{2\left(\frac{1}{12}\right)+\left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{6}-\frac{2}{3}}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{6}-\frac{4}{6}}=\frac{1}{-\frac{3}{6}}=\frac{1}{-\frac{1}{2}}=-2

\)

Second new root:

\(

\beta^{\prime}=\frac{1}{6 a+b}=\frac{1}{6\left(\frac{1}{12}\right)+\left(-\frac{2}{3}\right)}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{2}-\frac{2}{3}}=\frac{1}{\frac{3}{6}-\frac{4}{6}}=\frac{1}{-\frac{1}{6}}=-6

\)

Step 3: Form the new quadratic equation

A quadratic equation with roots \(\alpha^{\prime}\) and \(\beta^{\prime}\) can be written as \(x^2-\left(\alpha^{\prime}+\beta^{\prime}\right) x+\left(\alpha^{\prime} \beta^{\prime}\right)=0\).

Sum of the new roots:

\(

\alpha^{\prime}+\beta^{\prime}=-2+(-6)=-8

\)

Product of the new roots:

\(

\alpha^{\prime} \beta^{\prime}=(-2) \times(-6)=12

\)

The new quadratic equation is:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x^2-(-8) x+12=0 \\

x^2+8 x+12=0

\end{gathered}

\)

The quadratic equation, whose roots are \(\frac{1}{2 a+b}\) and \(\frac{1}{6 a+b}\), is \(x^2+8 x+12=0\). -

Question 20 of 101

20. Question

Let \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) be the roots of the equation \(p x^2+q x-r=0\), where \(p \neq 0\). If \(p, q\) and \(r\) be the consecutive terms of a non constant G.P. and \(\frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\beta}=\frac{3}{4}\), then the value of \((\alpha-\beta)^2\) is : [JEE Main 2024 (Online) 1st February Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(d) Step 1: Establish relationships between roots and coefficients

Given the quadratic equation \(p x^2+q x-r=0\), the sum and product of the roots \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are:

\(

\begin{aligned}

\alpha+\beta & =-\frac{q}{p} \\

\alpha \beta & =-\frac{r}{p}

\end{aligned}

\)

The coefficients \(\boldsymbol{p}, \boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{r}\) are consecutive terms of a non-constant geometric progression (G.P.). This means there is a common ratio \(k\) such that \(q=p k\) and \(r=q k=p k^2\). Since the G.P. is non-constant, \(k \neq 1\).

Step 2: Use the given information to find the common ratio

We are given the condition \(\frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\beta}=\frac{3}{4}\).

We can simplify the left side of the equation:

\(

\frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\beta}=\frac{\alpha+\beta}{\alpha \beta}

\)

Substitute the expressions for the sum and product of the roots in terms of \(\boldsymbol{p}, \boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{r}\) :

\(

\frac{\alpha+\beta}{\alpha \beta}=\frac{-q / p}{-r / p}=\frac{q}{r}

\)

Since \(\boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{r}\) are terms in a G.P. with common ratio \(\boldsymbol{k}\), we have \(\boldsymbol{r}=\boldsymbol{q} \boldsymbol{k}\).

\(

\frac{q}{r}=\frac{q}{q k}=\frac{1}{k}

\)

So, we have \(\frac{1}{k}=\frac{3}{4}\), which implies \(k=\frac{4}{3}\).

Step 3: Calculate the value of \((\alpha-\beta)^2\)

We know that \((\alpha-\beta)^2=(\alpha+\beta)^2-4 \alpha \beta\).

Substitute the expressions for the sum and product of the roots:

\(

(\alpha-\beta)^2=\left(-\frac{q}{p}\right)^2-4\left(-\frac{r}{p}\right)=\frac{q^2}{p^2}+\frac{4 r}{p}

\)

Since \(q=p k\) and \(r=p k^2\), we can substitute these into the equation:

\(

(\alpha-\beta)^2=\frac{(p k)^2}{p^2}+\frac{4\left(p k^2\right)}{p}=\frac{p^2 k^2}{p^2}+4 k^2=k^2+4 k^2=5 k^2

\)

Finally, substitute the value of \(k=\frac{4}{3}\) that we found in the previous step:

\(

(\alpha-\beta)^2=5\left(\frac{4}{3}\right)^2=5\left(\frac{16}{9}\right)=\frac{80}{9}

\) -

Question 21 of 101

21. Question

Let \(\mathbf{S}=\left\{x \in \mathbf{R}:(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^x+(\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2})^x=10\right\}\). Then the number of elements in \(S\) is : [JEE Main 2024 (Online) 1st February Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(c) Step 1: Simplify the equation

Let’s analyze the given equation:

\(

(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^x+(\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2})^x=10

\)

Notice that the two bases are reciprocals of each other.

\(

(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})(\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2})=(\sqrt{3})^2-(\sqrt{2})^2=3-2=1

\)

This implies that \(\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2}}\).

Let \(y=(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^x\). Since \(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2}>1\), for any real number \(x\), the value of \(y\) will be a positive real number, so \(y>0\).

Then the second term is \((\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2})^x=\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2}}\right)^x=\frac{1}{y}\).

Substituting these into the original equation, we get a quadratic equation in terms of \(y\) :

\(

y+\frac{1}{y}=10

\)

\(

y^2-10 y+1=0

\)

\(

y=5 \pm 2 \sqrt{6}

\)

So, the two possible values for \(y\) are \(y_1=5+2 \sqrt{6}\) and \(y_2=5-2 \sqrt{6}\).

Step 3: Find the values of \(\boldsymbol{x}\)

Now, we substitute back \(y=(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^x\) and solve for \(x\) for each value of \(y\).

First, let’s simplify the values of \(y_1\) and \(y_2\) :

\(

\begin{aligned}

y_1 & =5+2 \sqrt{6}=(\sqrt{3})^2+(\sqrt{2})^2+2 \sqrt{3} \sqrt{2}=(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^2 \\

y_2=5-2 \sqrt{6} & =(\sqrt{3})^2+(\sqrt{2})^2-2 \sqrt{3} \sqrt{2}=(\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2})^2

\end{aligned}

\)

Alternatively, using the reciprocal property, since \((\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})(\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2})=1\), we can see that \(5-2 \sqrt{6}=\frac{1}{5+2 \sqrt{6}}=\frac{1}{(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^2}=(\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2})^2\).

Case 1: \(y_1=5+2 \sqrt{6}\)

\(

(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^x=(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^2

\)

By comparing the exponents, we get \(x=2\).

Case 2: \(y_2=5-2 \sqrt{6}\)

\(

(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^x=(\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2})^2

\)

Since \(\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{2}=(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^{-1}\), we can write:

\(

(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^x=\left((\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^{-1}\right)^2=(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{2})^{-2}

\)

By comparing the exponents, we get \(x=-2\).

The set \(S\) contains the solutions \(x=2\) and \(x=-2\). Since these are two distinct real numbers, the number of elements in the set \(S\) is 2. -

Question 22 of 101

22. Question

Let \(S\) be the set of positive integral values of \(a\) for which \(\frac{a x^2+2(a+1) x+9 a+4}{x^2-8 x+32}<0, \forall x \in \mathbb{R}\). Then, the number of elements in \(S\) is : [JEE Main 2024 (Online) 31st January Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) For the inequality \(\frac{a x^2+2(a+1) x+9 a+4}{x^2-8 x+32}<0\) to be true for all real values of \(x\), we must analyze the numerator and denominator separately.

Step 1: Analyze the denominator

Let the denominator be \(\boldsymbol{D}(\boldsymbol{x})=\boldsymbol{x}^2-8 \boldsymbol{x}+32\). This is a quadratic expression with a leading coefficient of 1 (which is positive). To determine the sign of \(\boldsymbol{D}(\boldsymbol{x})\), we can calculate its discriminant, \(\boldsymbol{\Delta}_{\boldsymbol{D}}\).

The discriminant is given by \(\boldsymbol{\Delta}_{\boldsymbol{D}}=\boldsymbol{b}^2-4 a c\).

Here, \(a=1, b=-8\), and \(c=32\).

\(

\Delta_D=(-8)^2-4(1)(32)=64-128=-64

\)

Since the discriminant is negative ( \(\boldsymbol{\Delta}_{\boldsymbol{D}}<0\) ) and the leading coefficient is positive ( \(1>0\) ), the quadratic \(x^2-8 x+32\) is always positive for all real values of \(x\).

Step 2: Analyze the numerator

For the entire fraction to be negative, the numerator, \(N(x)=a x^2+2(a+1) x+9 a+4\), must be negative for all real values of \(x\), because the denominator is always positive.

For a quadratic expression \(\boldsymbol{N}(\boldsymbol{x})=\boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{x}^2+\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{x}+\boldsymbol{C}\) to be always negative, two conditions must be satisfied:

1. The leading coefficient, \(\boldsymbol{A}\), must be negative ( \(\boldsymbol{A}<0\) ).

2. The discriminant, \(\Delta_N\), must be negative ( \(\Delta_N<0\) ).

In our numerator, we have:

\(

\begin{gathered}

A=a \\

B=2(a+1) \\

C=9 a+4

\end{gathered}

\)

Applying the first condition, we must have \(\boldsymbol{a}<0\).

However, the problem states that \(a\) is a positive integral value. This means \(a \geq 1\). This directly contradicts the condition that a must be negative.

Since there are no positive integral values of \(\boldsymbol{a}\) that can satisfy the condition \(\boldsymbol{a}<0\), there are no such values of \(a\) for which the inequality holds for all real \(x\).

The number of elements in the set S is 0. -

Question 23 of 101

23. Question

If \(\alpha, \beta\) are the roots of the equation, \(x^2-x-1=0\) and \(S_n=2023 \alpha^n+2024 \beta^n\), then : [JEE Main 2024 (Online) 27th January Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(b) Step 1: Establish the recurrence relation for the roots

The roots \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) of the equation \(x^2-x-1=0\) must satisfy the equation. Therefore, we have:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \alpha^2-\alpha-1=0 \\

& \beta^2-\beta-1=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Rearranging these equations, we get:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \alpha^2=\alpha+1 \\

& \beta^2=\beta+1

\end{aligned}

\)

To find a general recurrence relation for powers of the roots, we can multiply each equation by \(\alpha^{n-2}\) and \(\beta^{n-2}\) respectively:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \alpha^n=\alpha^{n-1}+\alpha^{n-2} \\

& \beta^n=\beta^{n-1}+\beta^{n-2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 2: Establish the recurrence relation for \(S_n\)

The sequence \(S_n\) is defined as \(S_n=2023 \alpha^n+2024 \beta^n\). We can use the recurrence relations from the previous step to find a relation for \(S_n\).

Let’s consider the expression \(S_n-S_{n-1}-S_{n-2}\) :

\(

S_n-S_{n-1}-S_{n-2}=\left(2023 \alpha^n+2024 \beta^n\right)-\left(2023 \alpha^{n-1}+2024 \beta^{n-1}\right)-\left(2023 \alpha^{n-2}+2024 \beta^{n-2}\right)

\)

Group the terms by their coefficients:

\(

=2023\left(\alpha^n-\alpha^{n-1}-\alpha^{n-2}\right)+2024\left(\beta^n-\beta^{n-1}-\beta^{n-2}\right)

\)

Using the recurrence relations from Step 1, we know that \(\alpha^n-\alpha^{n-1}-\alpha^{n-2}=0\) and \(\beta^n-\beta^{n-1}-\beta^{n-2}=0\).

Substituting these values, we get:

\(

S_n-S_{n-1}-S_{n-2}=2023(0)+2024(0)=0

\)

Therefore, the recurrence relation for the sequence \(S_n\) is:

\(

S_n=S_{n-1}+S_{n-2}

\)

Step 3: Find the relationship for \(S_{12}, S_{11}, S_{10}\)

We can find the relationship between \(S_{12}, S_{11}\), and \(S_{10}\) by substituting \(n=12\) into the recurrence relation found in Step 2:

\(

\begin{gathered}

S_{12}=S_{12-1}+S_{12-2} \\

S_{12}=S_{11}+S_{10}

\end{gathered}

\) -

Question 24 of 101

24. Question

The number of real roots of the equation \(x|x|-5|x+2|+6=0\), is : [JEE Main 2023 (Online) 15th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(b) Step 1: Analyze the cases based on absolute values

The equation involves two absolute value expressions, \(|x|\) and \(|x+2|\). The critical points where these expressions change their form are \(x=0\) and \(x=-2\). This divides the number line into three intervals: \(x<-2,-2 \leq x<0\), and \(x \geq 0\).

Step 2: Solve the equation for the interval \(x<-2\)

For this interval, \(|x|=-x\) and \(|x+2|=-(x+2)\).

Substituting these into the original equation:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x(-x)-5(-(x+2))+6=0 \\

-x^2+5(x+2)+6=0 \\

-x^2+5 x+10+6=0 \\

-x^2+5 x+16=0 \\

x^2-5 x-16=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Using the quadratic formula \(x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4 a c}}{2 a}\), the roots are:

\(

x=\frac{5 \pm \sqrt{(-5)^2-4(1)(-16)}}{2}=\frac{5 \pm \sqrt{25+64}}{2}=\frac{5 \pm \sqrt{89}}{2}

\)

The two possible roots are \(x_1=\frac{5+\sqrt{89}}{2}\) and \(x_2=\frac{5-\sqrt{89}}{2}\). Since \(\sqrt{89} \approx 9.43\), \(x_1 \approx \frac{5+9.43}{2} \approx 7.215\), which is not less than \(-2. x_2 \approx \frac{5-9.43}{2} \approx-2.215\), which is less than -2.

Therefore, there is one valid root in this interval: \(\mathbf{x}=\frac{\mathbf{5}-\sqrt{\mathbf{8 9}}}{\mathbf{2}}\).

Step 3: Solve the equation for the interval \(-2 \leq x<0\)

For this interval, \(|x|=-x\) and \(|x+2|=x+2\).

Substituting these into the original equation:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x(-x)-5(x+2)+6=0 \\

-x^2-5 x-10+6=0 \\

-x^2-5 x-4=0 \\

x^2+5 x+4=0 \\

(x+1)(x+4)=0

\end{gathered}

\)

The roots are \(x=-1\) and \(x=-4\). The only root that lies in the interval \(-2 \leq x<0\) is \(x=-1\).

Therefore, there is one valid root in this interval: \(\mathbf{x}=-\mathbf{1}\).

Step 4: Solve the equation for the interval \(\boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{\geq} \mathbf{0}\)

For this interval, \(|x|=x\) and \(|x+2|=x+2\).

Substituting these into the original equation:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x(x)-5(x+2)+6=0 \\

x^2-5 x-10+6=0 \\

x^2-5 x-4=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Using the quadratic formula, the roots are:

\(

x=\frac{5 \pm \sqrt{(-5)^2-4(1)(-4)}}{2}=\frac{5 \pm \sqrt{25+16}}{2}=\frac{5 \pm \sqrt{41}}{2}

\)

The two possible roots are \(x_3=\frac{5+\sqrt{41}}{2}\) and \(x_4=\frac{5-\sqrt{41}}{2}\). Since \(\sqrt{41} \approx 6.4\), \(x_3 \approx \frac{5+6.4}{2} \approx 5.7\), which is greater than or equal to \(0 . x_4 \approx \frac{5-6.4}{2} \approx-0.7\), which is not greater than or equal to 0.

Therefore, there is one valid root in this interval: \(x=\frac{5+\sqrt{\mathbf{4 1}}}{2}\).

The real roots of the equation are \(x=\frac{5-\sqrt{89}}{2}, x=-1\), and \(x=\frac{5+\sqrt{41}}{2}\). The total number of real roots is 3. -

Question 25 of 101

25. Question

Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the roots of the equation \(x^2-\sqrt{2} x+2=0\). Then \(\alpha^{14}+\beta^{14}\) is equal to [JEE Main 2023 (Online) 13th April Evening Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(d) Step 1: Calculate the magnitude and argument of the roots

The roots of the quadratic equation \(x^2-\sqrt{2} x+2=0\) are \(\alpha=\frac{\sqrt{2}+i \sqrt{6}}{2}\) and \(\beta=\frac{\sqrt{2}-i \sqrt{6}}{2}\).

To express a complex number in exponential form \(r e^{i \theta}\), we first find the magnitude \(r\) and the argument \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\).

For \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\) :

The magnitude is \(r=|\alpha|=\sqrt{\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)^2+\left(\frac{\sqrt{6}}{2}\right)^2}=\sqrt{\frac{2}{4}+\frac{6}{4}}=\sqrt{\frac{8}{4}}=\sqrt{2}\).

The argument is \(\theta=\arg (\alpha)=\arctan \left(\frac{\sqrt{6} / 2}{\sqrt{2} / 2}\right)=\arctan (\sqrt{3})=\frac{\pi}{3}\).

Therefore, \(\alpha=\sqrt{2} e^{i \frac{\pi}{3}}\).

For \(\beta\), we can use the property that it is the complex conjugate of \(\alpha\). Thus, the magnitude is the same, and the argument is the negative of \(\alpha\) ‘s argument. So, \(\beta=\sqrt{2} e^{-i \frac{\pi}{3}}\).

Step 2: Calculate the 14th power of the roots

Using De Moivre’s theorem, we raise the magnitude to the power of 14 and multiply the argument by 14.

For \(\alpha^{14}\) :

\(

\alpha^{14}=\left(\sqrt{2} e^{i \frac{\pi}{3}}\right)^{14}=(\sqrt{2})^{14} e^{i \frac{14 \pi}{3}}=2^7 e^{i \frac{14 \pi}{3}}=128 e^{i \frac{14 \pi}{3}}

\)

We can simplify the argument \(\frac{14 \pi}{3}\) by finding its principal value: \(\frac{14 \pi}{3}=\frac{12 \pi+2 \pi}{3}=4 \pi+\frac{2 \pi}{3}\). Since \(e^{i\left(4 \pi+\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)}=e^{i \frac{2 \pi}{3}}\), we have \(\alpha^{14}=128 e^{i \frac{2 \pi}{3}}\).

For \(\boldsymbol{\beta}^{\mathbf{1 4}}\) :

\(

\beta^{14}=\left(\sqrt{2} e^{-i \frac{\pi}{3}}\right)^{14}=(\sqrt{2})^{14} e^{-i \frac{14 \pi}{3}}=128 e^{-i \frac{14 \pi}{3}}

\)

Similarly, the simplified argument is \(-\frac{2 \pi}{3}\). So, \(\beta^{14}=128 e^{-i \frac{2 \pi}{3}}\).

Step 3: Add the 14th powers of the roots

To add \(\alpha^{14}\) and \(\beta^{14}\), we can use Euler’s formula, which states that \(e^{i x}=\cos (x)+i \sin (x)\).

\(

\begin{gathered}

\alpha^{14}+\beta^{14}=128 e^{i \frac{2 \pi}{3}}+128 e^{-i \frac{2 \pi}{3}} \\

=128\left(\cos \left(\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)+i \sin \left(\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)\right)+128\left(\cos \left(-\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)+i \sin \left(-\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)\right)

\end{gathered}

\)

Since \(\cos (-x)=\cos (x)\) and \(\sin (-x)=-\sin (x)\), this simplifies to:

\(

\begin{gathered}

=128\left(\cos \left(\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)+i \sin \left(\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)\right)+128\left(\cos \left(\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)-i \sin \left(\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)\right) \\

=128\left(2 \cos \left(\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)\right)

\end{gathered}

\)

The value of \(\cos \left(\frac{2 \pi}{3}\right)\) is \(-\frac{1}{2}\).

\(

=128(2)\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)=-128

\)

The sum of the 14th powers of the roots is -128. -

Question 26 of 101

26. Question

The set of all \(a \in \mathbb{R}\) for which the equation \(x|x-1|+|x+2|+a=0\) has exactly one real root, is : [JEE Main 2023 (Online) 13th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(a) Let

\(

f(x)=x|x-1|+|x+2|

\)

and we want the number of real roots of \(f(x)+a=0\), i.e. \(f(x)=-a\).

Step 1. Break into intervals

Breakpoints: \(x=-2,1\).

\(

f(x)= \begin{cases}-x^2-2, & x<-2 \\ -x^2+2 x+2, & -2 \leq x<1 \\ x^2+2, & x \geq 1\end{cases}

\)

Step 2. Shapes of each piece

For \(x<-2\) : \(f(x)=-x^2-2\), decreasing (parabola down).

For \(-2 \leq x<1\) : \(f(x)=-x^2+2 x+2\), concave down, vertex at \(x=1\) (value \(f\left(1^{-}\right)=3\) ).

For \(x \geq 1\) : \(f(x)=x^2+2\), increasing.

Continuity check:

\(

\begin{gathered}

f\left(-2^{-}\right)=-4-2=-6, \quad f\left(-2^{+}\right)=-(-2)^2+2(-2)+2=-6, \text { (continuous) } \\

f\left(1^{-}\right)=3, \quad f\left(1^{+}\right)=3, \text { (continuous) }

\end{gathered}

\)

So the graph goes:

\(

(-\infty,-2): f \downarrow \text { to }-6, \quad(-2,1): f \uparrow \text { from }-6 \text { to } 3, \quad(1, \infty): f \uparrow \text { from } 3 \text { to } \infty .

\)

Step 3. Range and monotonic behavior

The only local minimum is at \(x=-2(f=-6)\); after that \(f\) increases forever.

Thus:

\(

f(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{l}

\text { decreasing on }(-\infty,-2), \\

\text { increasing on }[-2, \infty) .

\end{array}\right.

\)

So \(f\) has exactly one turning point (a minimum value -6 ).

Step 4. Number of roots of \(f(x)+a=0\)

We solve \(f(x)=-a\).

If \(-a<-6 \Rightarrow a>6\) : no intersection on the right side, but one intersection on decreasing left side \(\Rightarrow\) 1 root.

If \(-a=-6 \Rightarrow a=6\) : one intersection (at \(x=-2\) ) \(\Rightarrow 1\) root.

If \(-6<-a<3 \Rightarrow-3<a<6\) ? wait compute properly:

For \(f\) range \([-6, \infty)\), when \(f=-a\) lies in ( \(-6,3\) ), it cuts the increasing right part once (since left decreasing branch also covers values \(\leq-6\) only). Actually for \(-6<f<3\), there is one intersection on the increasing part \([-2, \infty)\).

Wait check: \(f\) on ( \(-2,1\) ) rises from -6 to 3 – gives one intersection there. So 1 root.

If \(-a=3 \Rightarrow a=-3\) : one root at \(x=1\).

If \(-a>3 \Rightarrow a<-3\) : line \(y=-a\) above \(3 \rightarrow\) intersects the rightmost branch \(f=x^2+2\) once \(\Rightarrow 1\) root.

For every \(a \in \mathbb{R}\), there is exactly one intersection.

\(

A=\mathbb{R}

\)

Hence, the equation \(x|x-1|+|x+2|+a=0\) has exactly one real root for all real \(a\). -

Question 27 of 101

27. Question

Let \(\alpha, \beta\) be the roots of the quadratic equation \(x^2+\sqrt{6} x+3=0\). Then \(\frac{\alpha^{23}+\beta^{23}+\alpha^{14}+\beta^{14}}{\alpha^{15}+\beta^{15}+\alpha^{10}+\beta^{10}}\) is equal to: [JEE Main 2023 (Online) 12th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(d) Step 1: Simplify the arguments of the cosine function

The cosine function has a period of \(2 \pi\). We can simplify the arguments by finding the remainder when the numerator is divided by the denominator, adjusted for the period.

\(\cos \left(\frac{69 \pi}{4}\right)=\cos \left(17 \pi+\frac{\pi}{4}\right)=\cos \left(\pi+\frac{\pi}{4}\right)=-\cos \left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)=-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\)

\(\cos \left(\frac{42 \pi}{4}\right)=\cos \left(\frac{21 \pi}{2}\right)=\cos \left(10 \pi+\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=\cos \left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=0\)

\(\cdot \cos \left(\frac{45 \pi}{4}\right)=\cos \left(11 \pi+\frac{\pi}{4}\right)=\cos \left(\pi+\frac{\pi}{4}\right)=-\cos \left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)=-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\)

\(\cos \left(\frac{30 \pi}{4}\right)=\cos \left(\frac{15 \pi}{2}\right)=\cos \left(7 \pi+\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=\cos \left(\pi+\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=-\cos \left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=0\)

Step 2: Substitute the simplified values into the expression

The expression is given as:

\(

\frac{(\sqrt{3})^{15}\left(2 \cos \frac{69 \pi}{4}\right)+(\sqrt{3})^6\left(2 \cos \frac{42 \pi}{4}\right)}{(\sqrt{3})^7\left(2 \cos \frac{45 \pi}{4}\right)+(\sqrt{3})^2\left(2 \cos \frac{30 \pi}{4}\right)}

\)

Substituting the simplified cosine values:

\(

\begin{gathered}

=\frac{(\sqrt{3})^{15}\left(2\left(-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)\right)+(\sqrt{3})^6(2(0))}{(\sqrt{3})^7\left(2\left(-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)\right)+(\sqrt{3})^2(2(0))} \\

=\frac{(\sqrt{3})^{15}(-\sqrt{2})}{(\sqrt{3})^7(-\sqrt{2})}

\end{gathered}

\)

The \((-\sqrt{2})\) terms cancel out, leaving:

\(

=\frac{(\sqrt{3})^{15}}{(\sqrt{3})^7}

\)

Step 3: Simplify the expression using exponent rules

Using the rule \(\frac{a^m}{a^n}=a^{m-n}\) :

\(

=(\sqrt{3})^{15-7}=(\sqrt{3})^8

\)

Since \(\sqrt{3}=3^{\frac{1}{2}}\), we have:

\(

\begin{gathered}

=\left(3^{\frac{1}{2}}\right)^8=3^{\frac{1}{2} \cdot 8}=3^4 \\

=81

\end{gathered}

\) -

Question 28 of 101

28. Question

Let \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma\) be the three roots of the equation \(x^3+b x+c=0\). If \(\beta \gamma=1=-\alpha\), then \(b^3+2 c^3-3 \alpha^3-6 \beta^3-8 \gamma^3\) is equal to : [JEE Main 2023 (Online) 8th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(b) To solve the problem step by step, we start with the given information about the roots of the polynomial equation \(\boldsymbol{x}^{\mathbf{3}}+\boldsymbol{b} \boldsymbol{x}+\boldsymbol{c}=\mathbf{0}\).

Step 1: Understand the roots

Let \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma\) be the roots of the equation. We are given that:

\(

\beta \gamma=1 \quad \text { and } \quad \alpha=-1

\)

Step 2: Use Vieta’s Formulas

From Vieta’s formulas, we know:

1. The sum of the roots:

\(

\begin{gathered}

\alpha+\beta+\gamma=0 \Longrightarrow-1+\beta+\gamma=0 \Longrightarrow \beta+\gamma \\

=1

\end{gathered}

\)

2. The sum of the products of the roots taken two at a time:

\(

\alpha \beta+\beta \gamma+\alpha \gamma=b

\)

Step 3: Substitute \(\alpha\) into the equations

Substituting \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}=-\mathbf{1}\) into the second equation:

\(

-1 \cdot \beta+\beta \cdot \gamma-1 \cdot \gamma=b \Longrightarrow-\beta+1-\gamma=b .

\)

Since \(\beta+\gamma=1\), we can express \(\gamma\) as:

\(

\gamma=1-\beta

\)

Substituting this into the equation gives:

\(

\begin{aligned}

-\beta+1-(1-\beta) & =b \Longrightarrow-\beta+1-1+\beta=b \\

& \Longrightarrow b=0

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 4: Find \(\boldsymbol{c}\)

Using the product of the roots:

\(

\alpha \beta \gamma=-c \Longrightarrow(-1) \cdot \beta \cdot \gamma=-c

\)

Since \(\beta \gamma=1\), we have:

\(

-1=-c \Longrightarrow c=1

\)

Step 5: Substitute \(\boldsymbol{b}\) and \(\boldsymbol{c}\) into the expression

Now we substitute \(b=0\) and \(c=1\) into the expression:

\(

b^3+2 c^3-3 \alpha^3-6 \beta^3-8 \gamma^3

\)

Calculating each term:

\(b^3=0^3=0\)

\(c^3=1^3=1 \Longrightarrow 2 c^3=2 \cdot 1=2\),

\(\alpha^3=(-1)^3=-1 \Longrightarrow-3 \alpha^3=-3(-1)=3\).

Step 6: Calculate \(\beta^3\) and \(\gamma^3\)

Since \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\) are the roots of the quadratic \(x^2-x+1=0\), we can find: – The roots are \(\beta=-\omega\) and \(\gamma=-\omega^2\) where \(\omega=e^{2 \pi / 3}\) (the cube roots of unity).

We know \(\beta^3=(-\omega)^3=-\omega^3=-1\) and \(\gamma^3=\left(-\omega^2\right)^3=-\left(\omega^2\right)^3=-1\)

Thus:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& -6 \beta^3=-6(-1)=6 \\

& -8 \gamma^3=-8(-1)=8

\end{aligned}

\)

Step 7: Combine all the terms

Now we combine all the terms:

\(

0+2+3+6+8=19

\)

Thus, the value of the expression \(b^3+2 c^3-3 \alpha^3-6 \beta^3-8 \gamma^3\) is: 19. -

Question 29 of 101

29. Question

Let \(A=\{x \in R:[x+3]+[x+4] \leq 3\}\), \(B=\left\{x \in R: 3^x\left(\sum_{r=1}^{\infty} \frac{3}{10^r}\right)^{x-3}<3^{-3 x}\right\}\), where [t] denotes greatest integer function. Then, [JEE Main 2023 (Online) 6th April Morning Shift]

CorrectIncorrectHint

(c) Step 1: Solve for Set A

The set \(A\) is defined by the inequality \([x+3]+[x+4] \leq 3\), where \([t]\) is the greatest integer function.

Using the property \([t+n]=[t]+n\) for any integer \(n\), we can rewrite the inequality:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& {[x+3]=[x]+3} \\

& {[x+4]=[x]+4}

\end{aligned}

\)

Substituting these into the inequality gives:

\(

\begin{gathered}

([x]+3)+([x]+4) \leq 3 \\

2[x]+7 \leq 3 \\

2[x] \leq-4 \\

{[x] \leq-2}

\end{gathered}

\)