8.2 Binomial Theorem for Positive Integral Indices

Binomial Means:

The word “Binomial” comes from BI meaning two, and NOMIAL meaning terms. Thus, a binomial expression has two terms connected by operators ‘ + ‘ or ‘ – ‘.

Exponents of (a+b)

Let us have a look at the following identities done earlier. Let us start with an exponent of 0 and build upwards.

\(\begin{aligned}

& (a+b)^0=1, \quad a+b \neq 0\\

& (a+b)^1=a+b \\

& (a+b)^2=a^2+2 a b+b^2 \\

& (a+b)^3=a^3+3 a^2 b+3 a b^2+b^3 \\

& (a+b)^4=(a+b)^3(a+b)=a^4+4 a^3 b+6 a^2 b^2+4 a b^3+b^4

\end{aligned}

\)

In these expansions, we observe that there is a pattern.

- The total number of terms in the expansion is one more than the index. For example, in the expansion of \((a+b)^2\), the number of terms is 3 whereas the index of \((a+b)^2\) is 2.

- Powers of the first quantity ‘ \(a\) ‘ go on decreasing by 1 whereas the powers of the second quantity ‘ \(b\) ‘ increase by 1, in successive terms.

- In each term of the expansion, the sum of the indices of \(a\) and \(b\) is the same and is equal to the index of \(a+b\).

The Pattern

Let’s take the example of cube of \((a+b)\)

\(

a^3+3 a^2 b+3 a b^2+b^3

\)

Now, notice the exponents of a. They start at 3 and go down: \(3,2,1,0\) :

\(

a^3+3 a^2 b+3 a b^2+b^3

\)

Likewise, the exponents of b go upwards: \(0,1,2,3\) :

\(

a^3+3 a^2 b+3 a b^2+b^3

\)

If we number the terms 0 to \(n\), we get this:

\(

\begin{array}{cccc}

k=0 & k=1 & k=2 & k=3 \\

a^3 & a^2 & a & 1 \\

1 & b & b^2 & b^3

\end{array}

\)

Which can be brought together into this:

\(

a^{n-k} b^k

\)

Coefficients

Just look at the coefficients in the expression below; we will find a pattern like this as the exponent increases.

\(\begin{array}{lc}

(a+b)^0= & 1 \\

(a+b)^1= & a+b \\

(a+b)^2= & a^2+2 a b+b^2 \\

(a+b)^3= & a^3+3 a^2 b+3 a b^2+b^3 \\

(a+b)^4= & a^4+4 a^3 b+6 a^2 b^2+4 a b^3+b^4 \\

\end{array}

\)

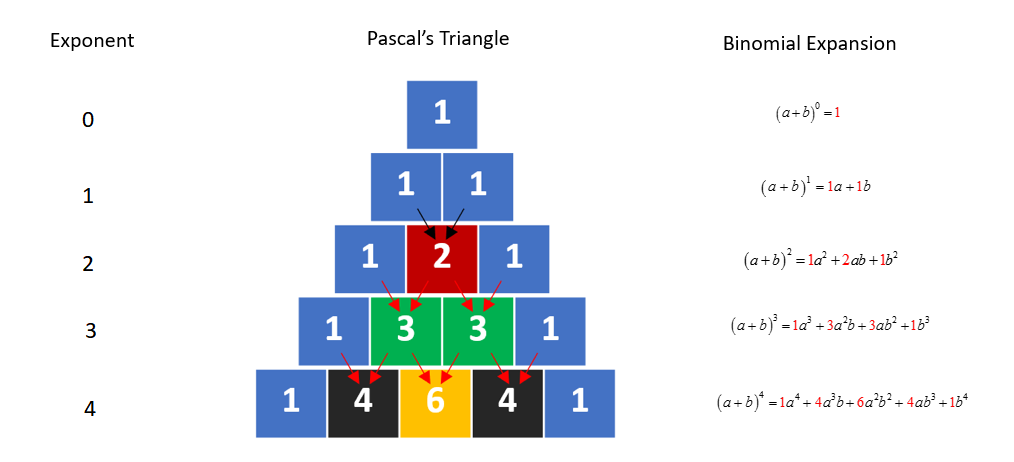

They actually form Pascal’s Triangle

Each number is just the two numbers above it added together (except for the edges, which are all “1”). It can be seen that the addition of 1’s in the row for index 1 gives rise to 2 in the row for index 2. The addition of 1, 2 and 2, 1 in the row for index 2, gives rise to 3 and 3 in the row for index 3 and so on. Also, 1 is present at the beginning and at the end of each row.

Pascal’s Triangle

This array of numbers shown above is known as Pascal’s triangle, after the name of French mathematician Blaise Pascal. It is also known as Meru Prastara by Pingla. Expansions for the higher powers of a binomial are also possible by using Pascal’s triangle.

Example 1: Let us expand \((2 x+3 y)^5\) by using Pascal’s triangle.

Solution:Using Pascal’s triangle we can find the row for index 5 is: 1 5 10 10 5 1

Using this row and our observations from above Pascal’s triangle, we get

\(\begin{aligned}

(2 x+3 y)^5 & =(2 x)^5+5(2 x)^4(3 y)+10(2 x)^3(3 y)^2+10(2 x)^2(3 y)^3+5(2 x)(3 y)^4+(3 y)^5 \\

& =32 x^5+240 x^4 y+720 x^3 y^2+1080 x^2 y^3+810 x y^4+243 y^5

\end{aligned}

\)

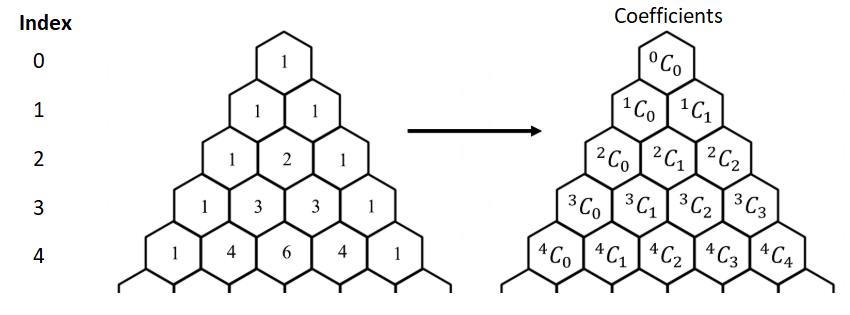

Pascal’s triangle using the concept of combinations

We make use of the concept of combinations studied earlier to rewrite the numbers in Pascal’s triangle. We know that \({ }^n \mathrm{C}_k=\frac{n !}{k !(n-k) !}, 0 \leq k \leq n\) and \(n\) is a non-negative integer. Also, \({ }^n \mathrm{C}_0=1={ }^n \mathrm{C}_n\) The Pascal’s triangle can now be rewritten as shown below.

Observing this pattern, we can now write the row of the Pascal’s triangle for any index without writing the earlier rows. For example, for the index 7 the row would be

\({ }^7 \mathrm{C}_0 { }^7 \mathrm{C}_1 { }^7 \mathrm{C}_2 { }^7 \mathrm{C}_3 { }^7 \mathrm{C}_4 { }^7 \mathrm{C}_5 { }^7 \mathrm{C}_6 { }^7 \mathrm{C}_7 .

\)

Example 2: Let’s expand \((a+b)^7\)

Solution:

\((a+b)^7={ }^7 \mathrm{C}_0 a^7+7 \mathrm{C}_1 a^6 b+{ }^7 \mathrm{C}_2 a^5 b^2+{ }^7 \mathrm{C}_3 a^4 b^3+{ }^7 \mathrm{C}_4 a^3 b^4+{ }^7 \mathrm{C}_5 a^2 b^5+{ }^7 \mathrm{C}_6 a b^6+{ }^7 \mathrm{C}_7 b^7

\)

Proof of Bionominal theorem for any positive integer

\((a+b)^n={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0 a^n+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1 a^{n-1} b+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2 a^{n-2} b^2+\ldots+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_{n-1} a \cdot b^{n-1}+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n b^n

\)

The proof can be obtained by applying the principle of mathematical induction. Let the given statement be

\(

\mathrm{P}(n):(a+b)^n={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0 a^n+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1 a^{n-1} b+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2 a^{n-2} b^2+\ldots+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_{n-1} a \cdot b^{n-1}+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n b^n

\)

For \(n=1\), we have

\(

\mathrm{P}(1):(a+b)^1={ }^1 \mathrm{C}_0 a^1+{ }^1 \mathrm{C}_1 b^1=a+b

\)

Thus, \(\mathrm{P}(1)\) is true.

Suppose \(\mathrm{P}(k)\) is true for some positive integer \(k\), i.e.

\(

(a+b)^k={ }^k \mathrm{C}_0 a^k+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_1 a^{k-1} b+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_2 a^{k-2} b^2+\ldots+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_k b^k \dots(1)

\)

We shall prove that \(\mathrm{P}(k+1)\) is also true, i.e.,

\(

(a+b)^{k+1}={ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_0 a^{k+1}+{ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_1 a^k b+{ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_2 a^{k-1} b^2+\ldots+{ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_{k+1} b^{k+1}

\)

Now, \((a+b)^{k+1}=(a+b)(a+b)^k\)

\(

=(a+b)\left({ }^k \mathrm{C}_0 a^k+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_1 a^{k-1} b+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_2 a^{k-2} b^2+\ldots+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_{k-1} a b^{k-1}+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_k b^k\right)

\)

[from (1)]

\(

\begin{aligned}

= & { }^k \mathrm{C}_0 a^{k+1}+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_1 a^k b+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_2 a^{k-1} b^2+\ldots+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_{k-1} a^2 b^{k-1}+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_k a b^k+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_0 a^k b \\

& +{ }^k \mathrm{C}_1 a^{k-1} b^2+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_2 a^{k-2} b^3+\ldots+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_{k-1} a b^k+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_k b^{k+1}

\end{aligned}

\)

[by actual multiplication]

\(

\begin{aligned}

& ={ }^k \mathrm{C}_0 a^{k+1}+\left({ }^k \mathrm{C}_1+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_0\right) a^k b+\left({ }^k \mathrm{C}_2+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_1\right) a^{k-1} b^2+\ldots \\

& +\left({ }^k \mathrm{C}_k+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_{k-1}\right) a b^k+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_k b^{k+1} \\

\end{aligned}

\)

[by grouping like terms]

\(

={ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_0 a^{k+1}+{ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_1 a^k b+{ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_2 a^{k-1} \mathrm{~b}^2+\ldots+{ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_k a b^k+{ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_{k+1} b^{k+1}

\)

\(

\text { (by using }{ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_0=1,{ }^k \mathrm{C}_r+{ }^k \mathrm{C}_{r-1}={ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_r \quad \text { and }{ }^k \mathrm{C}_k=1={ }^{k+1} \mathrm{C}_{k+1} \text { ) }

\)

Thus, it has been proved that \(\mathrm{P}(k+1)\) is true whenever \(\mathrm{P}(k)\) is true. Therefore, by the principle of mathematical induction, \(\mathrm{P}(n)\) is true for every positive integer \(n\).

Example 3: Expand using binomial theorem \((x+2)^6\)

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

(x+2)^6 & ={ }^6 \mathrm{C}_0 x^6+{ }^6 \mathrm{C}_1 x^5 \cdot 2+{ }^6 \mathrm{C}_2 x^4 2^2+{ }^6 \mathrm{C}_3 x^3 \cdot 2^3+{ }^6 \mathrm{C}_4 x^2 \cdot 2^4+{ }^6 \mathrm{C}_5 x \cdot 2^5+{ }^6 \mathrm{C}_6 \cdot 2^6 . \\

& =x^6+12 x^5+60 x^4+160 x^3+240 x^2+192 x+64

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus \((x+2)^6=x^6+12 x^5+60 x^4+160 x^3+240 x^2+192 x+64\).

Properties of Binomial Theorem

Property 1: \({ }^n C_r={ }^n C_{n-r}\)

Proof: By definition:

\(

{ }^n C_r=\frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}, \quad{ }^n C_{n-r}=\frac{n!}{(n-r)!r!}

\)

Clearly:

\(

{ }^n C_r={ }^n C_{n-r}

\)

For example: \(n=5, r=2\)

\(

\begin{gathered}

{ }^5 C_2=\frac{5!}{2!3!}=10 \\

{ }^5 C_{5-2}={ }^5 C_3=\frac{5!}{3!2!}=10

\end{gathered}

\)

Property 2: Sum of two consecutive binomial coefficients, \({ }^n C_r+{ }^n C_{r-1}={ }^{n+1} C_r\)

Proof: Write each term using factorials

\(

{ }^n C_r=\frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}, \quad{ }^n C_{r-1}=\frac{n!}{(r-1)!(n-r+1)!}

\)

\(

{ }^n C_r+{ }^n C_{r-1}=\frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}+\frac{n!}{(r-1)!(n-r+1)!}

\)

Rewrite both fractions with denominator \(r!(n-r+1)!\) :

\(

=\frac{n!(n-r+1)}{r!(n-r+1)!}+\frac{n!r}{r!(n-r+1)!}

\)

\(

=\frac{n![(n-r+1)+r]}{r!(n-r+1)!}=\frac{n!(n+1)}{r!(n-r+1)!}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Since }(n+1)!=(n+1) n!\text {, }\\

&\begin{gathered}

=\frac{(n+1)!}{r!(n+1-r)!} \\

={ }^{n+1} C_r

\end{gathered}

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

{ }^n C_r+{ }^n C_{r-1}={ }^{n+1} C_r

\)

For example, with \(n=5, r=3\)

For \(n=5\) and \(r=3\), the identity becomes \({ }^5 C_3+{ }^5 C_2={ }^6 C_3\).

The left side is \({ }^5 C_3+{ }^5 C_2\).

We calculate the individual terms:

\(

\begin{gathered}

{ }^5 C_3=\frac{5!}{3!2!}=\frac{5 \times 4 \times 3!}{3!\times 2 \times 1}=10 \\

{ }^5 C_2=\frac{5!}{2!3!}=10

\end{gathered}

\)

The sum is \(10+10=20\).

The right side is \({ }^6 C_3\).

We calculate this term:

\(

{ }^6 C_3=\frac{6!}{3!3!}=\frac{6 \times 5 \times 4 \times 3!}{3!\times 3 \times 2 \times 1}=\frac{120}{6}=20

\)

The identity holds: \(20=20\).

Property 3: \(r{ }^n C_r=n { }^{n-1} C_{r-1}\)

Proof: \({ }^n C_r=\frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}\)

Multiply both sides by \(r\) :

\(

r^n C_r=r \cdot \frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}

\)

Since \(r!=r(r-1)!\), cancel \(r\) :

\(

=\frac{n!}{(r-1)!(n-r)!}

\)

Write \(n!=n(n-1)!\) :

\(

=n \cdot \frac{(n-1)!}{(r-1)!(n-r)!}= n { }^{n-1} C_{r-1}

\)

For example, Let

\(

n=5, \quad r=2

\)

Left-hand side

\(

r^n C_r=2^5 C_2=2 \times \frac{5!}{2!3!}=2 \times 10=20

\)

Right-hand side

\(

n^{n-1} C_{r-1}=5^4 C_1=5 \times 4=20

\)

LHS = RHS

Property 4: Ratio of two consecutive binomial coefficients,\(\frac{{ }^n C_r}{{ }^n C_{r-1}}=\frac{n-r+1}{r}\)

Proof: \({ }^n C_r=\frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}, \quad{ }^n C_{r-1}=\frac{n!}{(r-1)!(n-r+1)!}\)

Now take the ratio:

\(

\frac{{ }^n C_r}{{ }^n C_{r-1}}=\frac{\frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}}{\frac{n!}{(r-1)!(n-r+1)!}}

\)

Cancel \(n!\) :

\(

=\frac{(r-1)!(n-r+1)!}{r!(n-r)!}

\)

Use

\(

\begin{gathered}

r!=r(r-1)!, \quad(n-r+1)!=(n-r+1)(n-r)! \\

=\frac{(r-1)!(n-r+1)(n-r)!}{r(r-1)!(n-r)!}

\end{gathered}

\)

Cancel common terms:

\(

=\frac{n-r+1}{r}

\)

For example, Let

\(

\begin{aligned}

& n=7, \quad r=3 \\

& \frac{{ }^7 C_3}{{ }^7 C_2}=\frac{35}{21}=\frac{5}{3}

\end{aligned}

\)

Right-hand side:

\(

\frac{7-3+1}{3}=\frac{5}{3}

\)

LHS = RHS

Property 5: If \({ }^n C_x={ }^n C_y\), then either \(x=y\) or \(x+y=n\). So, \({ }^n C_r={ }^n C_{n-r}=\frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}\)

For example 1: (Case: \(x=y\) )

Let

\(

\begin{gathered}

n=6, \quad x=2, \quad y=2 \\

{ }^6 C_2=\frac{6!}{2!4!}=15

\end{gathered}

\)

Since \(x=y\), the equality holds, and

\(

x+y=4 \neq 6 .

\)

For example 2: (Case: \(x+y=n\) )

Let

\(

\begin{gathered}

n=7, \quad x=2, \quad y=5 \\

{ }^7 C_2=\frac{7!}{2!5!}=21 \\

{ }^7 C_5=\frac{7!}{5!2!}=21

\end{gathered}

\)

Here,

\(

x+y=2+5=7=n .

\)

Property 6: \({ }^n C_0+{ }^n C_1+{ }^n C_2+\cdots+{ }^n C_n=2^n\)

Proof: The Binomial Theorem states that:

\(

(x+y)^n=\sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r x^{n-r} y^r

\)

Substitute \(x=1\) and \(y=1\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

(1+1)^n & =\sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r 1^{n-r} \cdot 1^r \\

2^n & =\sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r

\end{aligned}

\)

For example: \(n=5\)

\(

{ }^5 C_0+{ }^5 C_1+{ }^5 C_2+{ }^5 C_3+{ }^5 C_4+{ }^5 C_5=1+5+10+10+5+1=32 =2^5

\)

Property 7: \({ }^n C_0+{ }^n C_1+{ }^n C_2-\ldots+(-1)^n C_n=0\)

Proof: The Binomial Theorem states:

\(

(x+y)^n=\sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r x^{n-r} y^r

\)

Substitute \(x=1\) and \(y=-1\)

\(

\begin{gathered}

(1+(-1))^n=\sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r 1^{n-r}(-1)^r \\

0^n=\sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r(-1)^r \\

0={ }^n C_0-{ }^n C_1+{ }^n C_2-\cdots+(-1)^{n} { }^n C_n

\end{gathered}

\)

For example: \(n=4\)

\(

{ }^4 C_0-{ }^4 C_1+{ }^4 C_2-{ }^4 C_3+{ }^4 C_4=1-4+6-4+1=0

\)

Property 8: \({ }^n C_0+{ }^n C_2+{ }^n C_4+\cdots={ }^n C_1+{ }^n C_3+{ }^n C_5+\cdots=2^{n-1}\)

Proof: The Binomial Theorem states:

\(

(x+y)^n=\sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r x^{n-r} y^r

\)

Step 1: Sum of all coefficients

Set \(x=1\) and \(y=1\) :

\(

(1+1)^n=\sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r=2^n

\)

So the sum of all coefficients is \(2^n\).

Step 2: Alternating sum

Set \(x=1\) and \(y=-1\) :

\(

(1+(-1))^n=\sum_{r=0}^n{ }^n C_r(-1)^r=0

\)

So the alternating sum of coefficients is 0 :

\(

{ }^n C_0-{ }^n C_1+{ }^n C_2-{ }^n C_3+\cdots=0

\)

Step 3: Solve for even and odd sums

Let

\(

\begin{gathered}

S_{\text {even }}={ }^n C_0+{ }^n C_2+{ }^n C_4+\cdots \\

S_{\text {odd }}={ }^n C_1+{ }^n C_3+{ }^n C_5+\cdots

\end{gathered}

\)

From Step 1:

\(

S_{\mathrm{even}}+S_{\mathrm{odd}}=2^n

\)

From Step 2:

\(

S_{\text {even }}-S_{\text {odd }}=0

\)

Add the two equations:

\(

2 S_{\text {even }}=2^n \Rightarrow S_{\text {even }}=2^{n-1}

\)

Subtract the second from the first:

\(

2 S_{\text {odd }}=2^n \Rightarrow S_{\text {odd }}=2^{n-1}

\)

Hence proved.

For example: \(n=5\)

Even-indexed terms:

\(

{ }^5 C_0+{ }^5 C_2+{ }^5 C_4=1+10+5=16

\)

Odd-indexed terms:

\(

\begin{gathered}

{ }^5 C_1+{ }^5 C_3+{ }^5 C_5=5+10+1=16 \\

2^{5-1}=2^4=16

\end{gathered}

\)

Some special cases

Case-1: In the expansion of \((a+b)^n\) taking \(a=x \text { and } b=-y\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

(x-y)^n & =[x+(-y)]^n \\

& ={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0 x^n+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1 x^{n-1}(-y)+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2 x^{n-2}(-y)^2+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_3 x^{n-3}(-y)^3+\ldots+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n(-y)^n \\

& ={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0 x^n-{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1 x^{n-1} y+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2 x^{n-2} y^2-{ }^n \mathrm{C}_3 x^{n-3} y^3+\ldots+(-1)^n~{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n y^n

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus \((x-y)^n={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0 x^n-{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1 x^{n-1} y+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2 x^{n-2} y^2+\ldots+(-1)^n~{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n y^n\)

Euler’s theorem

Euler’s theorem is a rule that helps simplify large powers when working with remainders.

If \(\operatorname{gcd}(a, n)=1\)

(meaning \(a\) and \(n\) have no common factor other than 1 ), then

\(

a^{\varphi(n)} \equiv 1 \quad(\bmod n)

\)

where \(\varphi(n)\) is Euler’s totient function: \(\phi\left(p^k\right)=p^k-p^{k-1}\). For example, \(

\phi(25)=5^2-5^1=25-5=20

\)

the number of positive integers \(\leq n\) that are coprime to \(n\).

Illustration: Why Euler’s theorem applies here?

Find \(7^{42}(\bmod 15)\)

Solution:

Step 1: Verify Coprimality and Calculate Euler’s Totient Function

First, we verify that the base \(a=7\) and the modulus \(n=15\) are coprime; their greatest common divisor \(\operatorname{gcd}(7,15)=1\). Next, we calculate Euler’s totient function for \(n=15\).

\(

\phi(15)=\phi(3 \times 5)=\phi(3) \times \phi(5)=(3-1) \times(5-1)=2 \times 4=8

\)

Step 2: Apply Euler’s Theorem to Reduce the Exponent

Euler’s theorem states that if \(a\) and \(n\) are coprime, then \(a^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1(\bmod n)\). Applying this, we know that \(7^8 \equiv 1(\bmod 15)\). We then rewrite the original exponent, 42 , in terms of multiples of 8 :

\(

42=5 \times 8+2

\)

Using exponent rules, we express the original expression as:

\(

7^{42}=7^{5 \times 8+2}=\left(7^8\right)^5 \times 7^2

\)

Step 3: Simplify the Expression Modulo 15

Substitute the congruence from Euler’s theorem into the expression:

\(

\begin{aligned}

7^{42} & \equiv(1)^5 \times 7^2 \quad(\bmod 15) \\

7^{42} & \equiv 1 \times 49 \quad(\bmod 15)

\end{aligned}

\)

Finally, we calculate the remainder of 49 when divided by 15 :

\(

\begin{gathered}

49=3 \times 15+4 \\

49 \equiv 4 \quad(\bmod 15)

\end{gathered}

\)

The remainder when \(7^{42}\) is divided by 15 is 4.

Example 4: Evaluate \((x-2 y)^5\)

Solution:

\(\begin{aligned}

(x-2 y)^5= & { }^5 \mathrm{C}_0 x^5-{ }^5 \mathrm{C}_1 x^4(2 y)+{ }^5 \mathrm{C}_2 x^3(2 y)^2-{ }^5 \mathrm{C}_3 x^2(2 y)^3+ \\

& { }^5 \mathrm{C}_4 x(2 y)^4-{ }^5 \mathrm{C}_5(2 y)^5 \\

= & x^5-10 x^4 \mathrm{y}+40 x^3 y^2-80 x^2 y^3+80 x y^4-32 y^5 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Case-2: In the expansion of \((a+b)^n\) taking \(a=1 \text { and } b=x\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

(1+x)^n & ={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0(1)^n+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1(1)^{n-1} x+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2(1)^{n-2} x^2+\ldots+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n x^n \\

& ={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1 x+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2 x^2+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_3 x^3+\ldots+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n x^n

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus \(\quad(1+x)^n={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1 x+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2 x^2+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_3 x^3+\ldots+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n x^n\)

In particular, for \(x=1\), we have

\(

2^n={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2+\ldots+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n

\)

Case-3: In the expansion of \((a+b)^n\) taking \(a=1 \text { and } b=-x\).

\(

(1-x)^n={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0-{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1 x+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2 x^2-\ldots+(-1)^n{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n x^n

\)

In particular, for \(x=1\), we get

\(

0={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0-{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2-\ldots+(-1)^n{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n

\)

Example 5: \(\text { Expand }\left(x^2+\frac{3}{x}\right)^4, x \neq 0\)

Solution:

By using binomial theorem, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

\left(x^2+\frac{3}{x}\right)^4 & ={ }^4 \mathrm{C}_0\left(x^2\right)^4+{ }^4 \mathrm{C}_1\left(x^2\right)^3\left(\frac{3}{x}\right)+{ }^4 \mathrm{C}_2\left(x^2\right)^2\left(\frac{3}{x}\right)^2+{ }^4 \mathrm{C}_3\left(x^2\right)\left(\frac{3}{x}\right)^3+{ }^4 \mathrm{C}_4\left(\frac{3}{x}\right)^4 \\

& =x^8+4 \cdot x^6 \cdot \frac{3}{x}+6 \cdot x^4 \cdot \frac{9}{x^2}+4 \cdot x^2 \cdot \frac{27}{x^3}+\frac{81}{x^4} \\

& =x^8+12 x^5+54 x^2+\frac{108}{x}+\frac{81}{x^4} .

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 6: \(\text { Compute }(98)^5\)

Solution:

We express 98 as the sum or difference of two numbers whose powers are easier to calculate, and then use Binomial Theorem.

Write \(98=100-2\)

Therefore, \((98)^5=(100-2)^5\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

= & { }^5 \mathrm{C}_0(100)^5-{ }^5 \mathrm{C}_1(100)^4 \cdot 2+{ }^5 \mathrm{C}_2(100)^3 2^2 \\

& -{ }^5 \mathrm{C}_3(100)^2(2)^3+{ }^5 \mathrm{C}_4(100)(2)^4-{ }^5 \mathrm{C}_5(2)^5 \\

= & 10000000000-5 \times 100000000 \times 2+10 \times 1000000 \times 4-10 \times 10000 \\

& \times 8+5 \times 100 \times 16-32 \\

= & 10040008000-1000800032=9039207968 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 7: \(\text { Which is larger }(1.01)^{1000000} \text { or } 10,000 ?\)

Solution:

Splitting 1.01 and using binomial theorem to write the first few terms we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

(1.01)^{1000000} & =(1+0.01)^{1000000} \\

& ={ }^{1000000} \mathrm{C}_0+{ }^{10000000} \mathrm{C}_1(0.01)+\text { other positive terms } \\

& =1+1000000 \times 0.01+\text { other positive terms } \\

& =1+10000+\text { other positive terms } \\

& >10000

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence \(\quad(1.01)^{1000000}>10000\)

Example 8: Using binomial theorem, prove that \(6^n-5 n\) always leaves remainder 1 when divided by 25 .

Solution:

For two numbers \(a\) and \(b\) if we can find numbers \(q\) and \(r\) such that \(a=b q+r\), then we say that \(b\) divides \(a\) with \(q\) as quotient and \(r\) as remainder. Thus, in order to show that \(6^n-5 n\) leaves remainder 1 when divided by 25 , we prove that \(6^n-5 n=25 k+1\), where \(k\) is some natural number.

We have

\(

(1+a)^n={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1 a+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2 a^2+\ldots+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n a^n

\)

For \(a=5\), we get

\(

(1+5)^n={ }^n \mathrm{C}_0+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_1 5+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_2 5^2+\ldots+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_n 5^n

\)

i.e. \(\quad(6)^n=1+5 n+5^{2} { }^n \mathrm{C}_2+5^3 \cdot{ }^n \mathrm{C}_3+\ldots+5^n\)

i.e. \(\quad 6^n-5 n=1+5^2\left({ }^n \mathrm{C}_2+{ }^n \mathrm{C}_3 5+\ldots+5^{n-2}\right)\)

or \(\quad 6^n-5 n=1+25\left({ }^n \mathrm{C}_2+5 \cdot{ }^n \mathrm{C}_3+\ldots+5^{n-2}\right)\)

or \(\quad 6^n-5 n=25 k+1 \quad\) where \(k={ }^n \mathrm{C}_2+5 \cdot{ }^n \mathrm{C}_3+\ldots+5^{n-2}\).

This shows that when divided by \(25,6^n-5 n\) leaves remainder 1.

Example 9: What will be the remainder when \(7^{103}\) is divided by 25

Solution:

\(\begin{aligned}

& 7^{103}=7(50-1)^{51}=7\left(50^{51-}{ }^{51} C_1 50^{50}+{ }^{51} C_2 50^{49}-\ldots-1\right) \\

& =7\left(50^{51-}{ }^{51} C_1 50^{50}+\ldots+{ }^{51} C_{50} 50\right)-7-18+18 \\

& =7\left(50^{51-}{ }^{51} C_1 50^{50}+\ldots+{ }^{51} C_{50} 50\right)-25+18 \\

& \Rightarrow \text { remainder is } 18 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Alternate: Step 1: Calculate the Euler totient of 25

First, we determine the totient of \(n=25\), denoted as \(\phi(25)\). Since \(25=5^2\), the formula for the totient is \(\phi\left(p^k\right)=p^k-p^{k-1}\).

\(

\phi(25)=5^2-5^1=25-5=20

\)

Step 2: Apply Euler’s theorem

Euler’s theorem states that if \(\operatorname{gcd}(a, n)=1\), then \(a^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1(\bmod n)\). Here, \(\operatorname{gcd}(7,25)=1\), so:

\(

7^{20} \equiv 1 \quad(\bmod 25)

\)

Step 3: Reduce the exponent

We express the exponent 103 in terms of the totient 20 to simplify the expression \(7^{103}(\bmod 25)\).

\(

\begin{gathered}

103=5 \times 20+3 \\

7^{103}=7^{(5 \times 20+3)}=\left(7^{20}\right)^5 \times 7^3

\end{gathered}

\)

Step 4: Calculate the final remainder

Using the result from Euler’s theorem \(\left(7^{20} \equiv 1(\bmod 25)\right)\), we substitute this back into the expression:

\(

\begin{gathered}

\left(7^{20}\right)^5 \times 7^3 \equiv(1)^5 \times 7^3 \quad(\bmod 25) \\

7^3=343 \\

343 \quad(\bmod 25)=18

\end{gathered}

\)

Example 10: \(\text { What will be the last two digits of } 11^{25} \text { ? }\)

Solution:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 11^{25}=(1+10)^{25}=\left(\begin{array}{c}

25 \\

0

\end{array}\right)+10 \cdot\left(\begin{array}{c}

25 \\

1

\end{array}\right)+\sum_{k=2}^{25}\left(\begin{array}{c}

25 \\

k

\end{array}\right) \cdot 10^k \\

& =1+25 \cdot 10+\sum_{k=2}^{25}\left(\begin{array}{c}

25 \\

k

\end{array}\right) \cdot 10^k \\

& =1+250+10^2 \cdot\left(\sum_{k=2}^{25}\left(\begin{array}{c}

25 \\

k

\end{array}\right) \cdot 10^{k-2}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

Hence, the last two digits are 5 and 1

Example 11: If \(n\) is a positive integer, prove that \(3^{3 n}-26 n-1\) is divisible by 676

Solution:

\(\begin{aligned}

& \left(3^{3 n}-26n-1\right)=(27)^n-26 n-1 \\

& =(1+26)^n-26 n-1 \\

& =1+26 n+(26)^2\left[{ }^n C_2+26^n C_3+ \dots +(26)^{n-2}\right]-26 n-1 \\

& \text { Let }\left[{ }^n C_2+26^n C_3+ \dots +(26)^{n-2}\right]=k \\

& =676 \mathrm{k} \\

& \therefore\left(3^{3 n}-26 n-1\right) \text { is divisible by } 676

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 12: Evaluate the following expression \((1+2 \sqrt{x})^5+(1-2 \sqrt{x})^5\)

Solution:

\((1+2 \sqrt{x})^5+(1-2 \sqrt{x})^5\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& =\left[{ }^5 C_0+{ }^5 C_1(2 \sqrt{x})+{ }^5 C_2(2 \sqrt{x})^2+ \dots +{ }^5 C_5(2 \sqrt{x})^5\right] \\

& +\left[{ }^5 C_0-{ }^5 C_1(2 \sqrt{x})+{ }^5 C_2(2 \sqrt{x})^2 + \dots -{ }^5 C_5(2 \sqrt{x})^5\right] \\

& =2\left[{ }^5 C_0+{ }^5 C_2(2 \sqrt{x})^2+{ }^5 C_4(2 \sqrt{x})^4\right] \\

& =2\left[1+10 \times 4 \times x+5 \times 16 x^2\right] \\

& =160 x^2+80 x+2

\end{aligned}

\)

Multinomial Expansions

Consider the expansion of \((x+y+z)^{10}\). In the expansion, each term has different powers of \(x, y\) and \(z\) and sum of these powers is always 10.

One of the terms is \(\lambda x^2 y^3 z^5\). Now, the coefficient of this term \(\lambda\) is equal to the number of ways \(2 x\) ‘s, \(3 y\) ‘s and \(5 z\) ‘s are arranged, i.e., \(10!/(2!3!5!)\). Thus,

\(

(x+y+z)^{10}=\sum \frac{10!}{P_{1}!P_{2}!P_{3}!} x^{P_1} y^{P_2} z^{P_3}

\)

where \(P_1+P_2+P_3=10\) and \(0 \leq P_1, P_2, P_3 \leq 10\). In general,

\(

\left(x_1+x_2+\cdots+x_r\right)^n=\sum \frac{n!}{P_{1}!P_{2}!\cdots P_{r}!} x_1^{P_1} x_2^{P_2} \cdots x_r^{P_r}

\)

where \(P_1+P_2+P_3+\cdots+P_r=n\) and \(0 \leq P_1, P_2, \ldots, P_r \leq n\).

Number of Terms in the Expansion of \(\left(x_1+x_2+\cdots+x_r\right)^n\)

From the general term of the above expansion, we can conclude that number of terms is equal to the number of ways different powers can be distributed to \(x_1, x_2, x_3, \ldots, x_n\) such that sum of powers is always \(n\).

Number of non-negative integral solutions of \(x_1+x_2+\cdots+ x_r=n\) is \({ }^{n+r-1} C_{r-1}\).

For example, number of terms in the expansion of \((x+y+z)^3\) is \({ }^{3+3-1} C_{3-1}={ }^5 C_2=10\).

Explanation: \(r=\) number of variables \((x, y, z \Longrightarrow r=3)\)

\(n=\) exponent ( \(n=3\) in this case)

Number of terms \(={ }^{n+r-1} C_{r-1}={ }^{3+3-1} C_{3-1}={ }^{5} C_{2}=10\)

Remark: Number of terms in \((x+y+z)^n\) is \({ }^{n+3-1} C_{3-1}={ }^{n+2} C_2\).

Number of terms in \((x+y+z+w)^n\) is \({ }^{n+4-1} C_{4-1}={ }^{n+3} C_3\) and so on .

Example 13: If the number of terms in the expansion of \((x+y+z)^n\) are 36, then find the value of \(n\).

Solution: Number of terms in the expansion of \((x+y+z)^n\) is \(=\binom{n+3-1}{3-1}=\binom{n+2}{2}\).

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\binom{n+2}{2}=\frac{(n+2)(n+1)}{2}=36\\

&(n+2)(n+1)=72

\end{aligned}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{gathered}

n^2+3 n+2=72 \\

n^2+3 n+2-72=0 \\

n^2+3 n-70=0

\end{gathered}\\

&\begin{aligned}

& (n+10)(n-7)=0 \\

& n=-10 \text { or } n=7

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Since \(n \geq 0\) in a binomial/multinomial expansion,

\(n=7\)

Example 14: Find the coefficient of \(a^3 b^4 c\) in the expansion of \((1+a-b+c)^9\).

Solution: Step 1: Identify the general term

The general term in the expansion of \(\left(x_1+x_2+\cdots+x_r\right)^n\) is given by the multinomial formula:

\(

\text { General term }=\frac{n!}{p_{1}!p_{2}!\ldots p_{m}!} x_1^{p_1} x_2^{p_2} \ldots x_r^{p_r}

\)

where \(p_1+p_2+\cdots+p_r=n\).

Here:

\(x_1=1\)

\(x_2=a\)

\(x_3=-b\)

\(x_4=c\)

and \(n=9\).

Step 2: Assign powers for the term we want

We want the term \(a^3 b^4 c\).

Let the powers in the expansion be:

\(

(1)^p(a)^q(-b)^r(c)^s

\)

with \(p+q+r+s=9\).

From \(a^3 b^4 c\) :

\(q=3\)

\(r=4\)

\(s=1\)

\(p=9-(3+4+1)=1\)

Step 3: Apply the multinomial formula

The coefficient is:

\(

\text { Coefficient }=\frac{9!}{p!q!r!s!} \cdot(\text { sign of each term })

\)

Here:

\(

p!=1!, \quad q!=3!, \quad r!=4!, \quad s!=1!

\)

Since \(b\) comes from \(-b\), we include the sign \((-1)^r=(-1)^4=+1\).

\(

\text { Coefficient }=\frac{9!}{1!\cdot 3!\cdot 4!\cdot 1!} \cdot 1

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Step 4: Compute factorials }\\

&\begin{aligned}

9! & =362880 \\

1!\cdot 3!\cdot 4!\cdot 1! & =1 \cdot 6 \cdot 24 \cdot 1=144 \\

\text { Coefficient } & =\frac{362880}{144}=2520

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

So, the coefficient of \(a^3 b^4 c\) in the expansion of \((1+a-b+c)^9\) is 2520.

Example 15: Find the coefficient of \(a^3 b^4 c^5\) in the expansion of \((b c+c a+a b)^6\).

Solution: In this case, write \(a^3 b^4 c^5=(a b)^x(b c)^y(c a)^z\) (say). Then,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& a^3 b^4 c^5=a^{z+x} b^{x+y} c^{y+z} \\

\Rightarrow \quad & z+x=3, x+y=4, y+z=5

\end{aligned}

\)

Adding all,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& 2(x+y+z)=12 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & x+y+z=6

\end{aligned}

\)

Then, \(x=1, y=3, z=2\).

Therefore, the coefficient of \(a^3 b^4 c^5\) in the expansion of \((b c+c a+a b)^6\) or the coefficient of \((a b)^1(b c)^3(c a)^2\) in the expansion of \((b c+c a+a b)^6\) is

\(6!/(x!y!z!)=6!/(1!3!2!)=60\).

Example 16: Find the coefficient of \(x^7\) in the expansion of \(\left(1+3 x-2 x^3\right)^{10}\).

Solution: Coefficient of \(x^7\) in the expansion of \(\left(1+3 x-2 x^3\right)^{10}\) is

\(

\sum \frac{10!}{n!n_{2}!n_{3}!}(1)^{n_1}(3 x)^{n_2}\left(-2 x^3\right)^{n_3}

\)

where:

\(n_1=\) number of times ” 1 ” is chosen,

\(n_2=\) number of times ” \(3 x\) ” is chosen,

\(n_3=\) number of times ” \(-2 x^3\) ” is chosen.

Determine which combinations give \(x^7\)

The power of \(x\) in the general term is:

\(

x^{n_2+3 n_3}

\)

We want \(n_2+3 n_3=7\).

where \(n_1+n_2+n_3=10\) and \(n_2+3 n_3=7\), the possible values of \(n_1, n_2\) and \(n_3\) are shown in the margin.

\(

\begin{array}{|c|c|c|}

\hline n_1 & n_2 & n_3 \\

\hline 3 & 7 & 0 \\

\hline 5 & 4 & 1 \\

\hline 7 & 1 & 2 \\

\hline

\end{array}

\)

Therefore the coefficient of \(x^7\) is

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{10!}{3!7!0!}(1)^3(3)^7(-2)^0+\frac{10!}{5!4!1!}(1)^5(3)^4(-2)^1 \\

& \quad+\frac{10}{7!1!2!}(1)^7(3)^1(-2)^2 \\

& =262440-204120+4320 \\

& =62640

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 17: The sum of the last eight coefficients in the expansion of \((1+x)^{15}\) is

(a) \(2^{16}\)

(b) \(2^{15}\)

(c) \(2^{14}\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (c) Step 1: Understand the expansion and properties

The binomial expansion of \((1+x)^n\) has \(n+1\) coefficients, given by the binomial coefficients \(C_r=\binom{n}{r}\) for \(r=0,1, \ldots, n\). For \(n=15\), there are \(15+1=16\) coefficients: \(C_0, C_1, \ldots, C_{15}\).

Step 2: Utilize the symmetry property

A key property of binomial coefficients is symmetry: \(C_r=C_{n-r}\). This means the coefficients from the beginning are the same as those from the end.

\(

C_0=C_{15}, C_1=C_{14}, \ldots, C_7=C_8

\)

The last eight coefficients are \(C_8+C_9+\ldots+C_{15}\), which is equal to the sum of the first eight coefficients, \(C_0+C_1+\ldots+C_7\).

Step 3: Calculate the total sum of coefficients

The sum of all coefficients in the expansion of \((1+x)^n\) is found by setting \(x=1\) in the expansion, which gives \((1+1)^n=2^n\) For \(n=15\), the total sum is \(2^{15}\).

Step 4: Determine the sum of the last eight coefficients

The total sum is the sum of the first eight coefficients plus the sum of the last eight coefficients:

\(

\text { Total Sum }=\left(C_0+\ldots+C_7\right)+\left(C_8+\ldots+C_{15}\right)

\)

Since the first and last eight sums are equal due to symmetry:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \text { Total Sum }=2 \times \text { (Sum of last eight coefficients) } \\

& 2^{15}=2 \times \text { (Sum of last eight coefficients) } \\

& \text { Sum of last eight coefficients }=\frac{2^{15}}{2}=2^{14}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 18: Find the sum \({ }^{10} C_1+{ }^{10} C_3+{ }^{10} C_5+{ }^{10} C_7 +{ }^{10} C_9\).

Solution: We know that

\(

2^{n-1}={ }^n C_0+{ }^n C_2+{ }^n C_4+\cdots={ }^n C_1+{ }^n C_3+{ }^n C_5+\cdots

\)

So, \({ }^{10} C_1+{ }^{10} C_3+{ }^{10} C_5+\cdots+{ }^{10} C_9=2^{10-1}=2^9\)

Example 19: Find the sum

\(

\frac{1}{1!(n-1)!}+\frac{1}{3!(n-3)}+\frac{1}{5!(n-5)}+\cdots

\)

Solution: \(\quad S=\frac{1}{1!(n-1)!}+\frac{1}{3!(n-3)!}+\frac{1}{5!(n-5)!}+\cdots\)

Multiplying each term by \(n!/ n!, S\) reduces to

\(

\begin{aligned}

S & =\frac{1}{n!}\left[\frac{n!}{1!(n-1)!}+\frac{1}{3!} \frac{n!}{(n-3)!}+\frac{1}{5!} \frac{n!}{(n-5)!}+\cdots\right] \\

& =\frac{1}{n!}\left[{ }^n C_1+{ }^n C_3+{ }^n C_5+\cdots\right] \\

& =\frac{2^{n-1}}{n!}

\end{aligned}

\)

Note: We know that in the expansion of \((1+1)^n=2^n\) and \((1-1)^n=0\), the sum of binomial coefficients with odd powers is: \(\left[{ }^n C_1+{ }^n C_3+{ }^n C_5+\cdots\right]=2^{n-1}\)

Example 20: Find the sum \(\sum_{k=0}^{10}{ }^{20} C_k\).

Solution: \(S=\sum_{k=0}^{10}{ }^{20} C_k={ }^{20} C_0+{ }^{20} C_1+\cdots+{ }^{20} C_{10}\)

Now, \({ }^{20} C_0+{ }^{20} C_1+\cdots+{ }^{20} C_9+{ }^{20} C_{10}+{ }^{20} C_{11}+\cdots+{ }^{20} C_{20}=2^{20}\)

\(

\Rightarrow\left({ }^{20} C_0+{ }^{20} C_{20}\right)+\left({ }^{20} C_1+{ }^{20} C_{19}\right)+\cdots+\left({ }^{20} C_9+{ }^{20} C_{11}\right)+{ }^{20} C_{10}=2^{20}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad 2\left[{ }^{20} C_0+{ }^{20} C_1+\cdots+{ }^{20} C_{10}\right]+{ }^{20} C_{10}=2{ }^{20}\left(\because{ }^n C_r={ }^n C_{n-r}\right) \\

& \therefore \quad S={ }^{20} C_0+{ }^{20} C_1+\cdots+{ }^{20} C_{10}=2^{19}-\frac{1}{2}{ }^{20} C_{10}

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 21: Find the sum of the series \({ }^{15} C_0+{ }^{15} C_1+ { }^{15} \boldsymbol{C}_2+\ldots \ldots \ldots+{ }^{15} \boldsymbol{C}_7\)

Solution: Let \(S={ }^{15} C_0+{ }^{15} C_1+{ }^{15} C_2+\ldots+{ }^{15} C_7\)

Here the series is exactly half series(8 terms)

As the full series (16 terms) will be \({ }^{15} C_0+{ }^{15} C_1+{ }^{15} C_2+\ldots+\)

\(

{ }^{15} C_7+{ }^{15} C_8+\ldots+{ }^{15} C_{15}

\)

So the sum of \(S\) is exactly half of the full series that is half of \(2^{15}\) which is \(2^{14}\)

Hence, \({ }^{15} C_0+{ }^{15} C_1+{ }^{15} C_2+\ldots+{ }^{15} C_7=2^{14}\).

Example 22: If the sum of coefficient of first half terms in the expansion of \((x+y)^n\) is 256 then find the greatest coefficient in the expansion.

Solution: Sum of coefficient of first half of the terms \(=2^{n-1}\) (half series) \(=256=2^8\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad n=9 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad \text { greatest coefficient }={ }^9 C_4=126

\end{aligned}

\)

Note: For \((x+y)^n\), the greatest coefficient occurs at:

\(

k=\left\lfloor\frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor

\)

Here, \(n=9\), so:

\(

k=\left\lfloor\frac{9}{2}\right\rfloor=4

\)

Sum of Coefficients in Binomial Expansion

For \((x+y)^n={ }^n C_0 x^n+{ }^n C_1 x^{n-1} y+{ }^n C_2 x^{n-2} y^2+\cdots+{ }^n C_n y^n\), we get the sum of coefficients by putting \(x=y=1\), which is \(2^n\).

For example: Sum of coefficients in \((2 x+3 y)^4\)

First, factor out constants:

\((2 x+3 y)^4 \rightarrow\) sum of coefficients is obtained by replacing \(x=1, y=1\) :

\(

(2 \cdot 1+3 \cdot 1)^4=(2+3)^4=5^4=625

\)

So the sum of coefficients is 625.

For example: Sum of coefficients in \((x-y)^5\)

Replace \(x=1, y=1\) :

\(

(1-1)^5=0

\)

So the sum of coefficients is \(\mathbf{0}\).

(Notice: alternating signs can cancel out the sum.)

Sum of Coefficients in Multinomial Expansion

Similarly, in the expansion of \((x+y+z)^n\), we get the sum of coefficients by putting \(x=y=z=1\).

For three variables:

\(

(x+y+z)^n=\sum \frac{n!}{p!q!r!} x^p y^q z^r, \quad p+q+r=n

\)

Sum of coefficients: Set \(x=y=z=1\) :

\(

\sum \frac{n!}{p!q!r!}=(1+1+1)^n=3^n

\)

For example : Sum of coefficients in \((x+y+z)^4\)

Replace \(x=y=z=1\) :

\(

(1+1+1)^4=3^4=81

\)

So the sum of coefficients is 81.

For example: Sum of coefficients in \((2 x-y+3 z)^3\)

Replace \(x=y=z=1\) :

\(

(2 \cdot 1-1+3 \cdot 1)^3=(2-1+3)^3=4^3=64

\)

Sum of coefficients is 64.

So, the general rule is:

- Binomial: \(x=y=1 \Longrightarrow \operatorname{sum}=2^n\)

- Trinomial: \(x=y=z=1 \Longrightarrow\) sum \(=3^n\)

- Multinomial: \(x_1=x_2=\cdots=x_r=1 \Longrightarrow\) sum \(=r^n\)

- In fact to find sum of coefficients we put the value of all variables as 1(where variables are in \(x^n\) form).

Example 23: Find the sum of coefficients for even and odd powers of \(x\) in a polynomial expansion like \(\left(x^2+x+1\right)^n\).

Solution: Sum of All Coefficients:

To get the sum of all coefficients, you correctly substitute all variables with 1. For the expansion:

\(

P(x)=\left(x^2+x+1\right)^n=a_0+a_1 x+a_2 x^2+\cdots+a_{2 n} x^{2 n}

\)

Substituting \(x=1\) gives:

\(

P(1)=\left(1^2+1+1\right)^n=3^n

\)

So, the sum of all coefficients is \(a_0+a_1+a_2+\cdots+a_{2 n}=3^n\).

Sum of Coefficients for Even and Odd Powers:

The coefficients of even and odd powers can be found using the following method:

Calculate the value of the polynomial at \(x=1(P(1))\) :

\(

P(1)=a_0+a_1+a_2+a_3+a_4+\cdots+a_{2 n}=3^n \dots(1)

\)

Calculate the value of the polynomial at \(x=-1(P(-1))\) :

Substituting \(x=-1\) into the polynomial results in:

\(

P(-1)=\left((-1)^2+(-1)+1\right)^n=(1-1+1)^n=1^n=1

\)

The expansion at \(\boldsymbol{x}=-1\) becomes:

\(

P(-1)=a_0-a_1+a_2-a_3+a_4-\cdots+a_{2 n}=1 \dots(2)

\)

Sum of coefficients of even powers of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) :

Add Equation 1 and Equation 2 to cancel out the odd-powered terms:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (P(1)+P(-1))=\left(a_0+a_1+a_2+\cdots\right)+\left(a_0-a_1+a_2-\cdots\right) \\

& 3^n+1=2 a_0+2 a_2+2 a_4+\cdots+2 a_{2 n} \\

& 3^n+1=2\left(a_0+a_2+a_4+\cdots+a_{2 n}\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

The sum of coefficients of even powers is:

\(

S_{\mathrm{even}}=a_0+a_2+a_4+\cdots+a_{2 n}=\frac{3^n+1}{2}

\)

Sum of coefficients of odd powers of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) :

Subtract Equation 2 from Equation 1 to cancel out the even-powered terms:

\(

\begin{aligned}

& (P(1)-P(-1))=\left(a_0+a_1+a_2+\cdots\right)-\left(a_0-a_1+a_2-\cdots\right) \\

& 3^n-1=2 a_1+2 a_3+2 a_5+\cdots \\

& 3^n-1=2\left(a_1+a_3+a_5+\cdots\right)

\end{aligned}

\)

The sum of coefficients of odd powers is:

\(

S_{\text {odd }}=a_1+a_3+a_5+\cdots=\frac{3^n-1}{2}

\)

For example: \(\left(x^2+x+1\right)^2=x^4+2 x^3+3 x^2+2 x+1\) :

Even coefficients sum \(\left(a_0+a_2+a_4\right): 1+3+1=5\)

Odd coefficients sum \(\left(a_1+a_3\right): 2+2=4\)

Using formula for \(n=2\).

Even: \(\frac{3^2+1}{2}=\frac{10}{2}=5\)

Odd: \(\frac{3^2-1}{2}=\frac{8}{2}=4\)

Example 24: Find the sum of all the coefficients in the binomial expansion of \(\left(\boldsymbol{x}^{\mathbf{2}} \boldsymbol{+} \boldsymbol{x}-\mathbf{3}\right)^{\mathbf{3 1 9}}\).

Solution: Putting \(x=1\) in \(\left(x^2+x-3\right)^{319}\), we get the sum of coefficients equal to \((1+1-3)^{319}=-1\).

Example 25: If the sum of the coefficients in the expansion of \(\left(\alpha^2 x^2-2 \alpha x+1\right)^{51}\) vanishes, then find the value of \(\alpha\).

Solution: The sum of the coefficients of the polynomial ( \(\alpha^2 x^2-2 \alpha x+1)^{51}\) is obtained by putting \(x=1\) in \(\left(\alpha^2 x^2-2 \alpha x+1\right)^{51}\). Hence, from the given condition,

\(

\left(\alpha^2-2 \alpha+1\right)^{5!}=0 \Rightarrow \alpha=1

\)

Example 26: If \(\left(1+x-2 x^2\right)^{20}=a_0+a_1 x+a_2 x^2+a_3 x^3+ \cdots+a_{40} x^{40}\), then find the value of \(a_1+a_3+a_5+\cdots+a_{39}\).

Solution: \(\left(1+x-2 x^2\right)^{20}=a_0+a_1 x+a_2 x^2+\cdots+a_{40} x^{40}\)

\(\begin{aligned} & \text { Putting } x=1 \text {, we get } \\ & \qquad a_0+a_1+a_2+a_3+\cdots+a_{40}=0\end{aligned} \dots(1)\)

Putting \(x=-1\), we get

\(

a_0-a_1+a_2-a_3+\cdots-a_{39}+a_{40}=2^{20} \dots(2)

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\text { Subtracting (1) from (2), we get }\\

&\begin{aligned}

& 2\left[a_1+a_3+\cdots+a_{39}\right]=-2^{20} \\

\Rightarrow \quad & a_1+a_3+\cdots+a_{39}=-2^{19}

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)