5.4 The Modulus and the Conjugate of a Complex Number

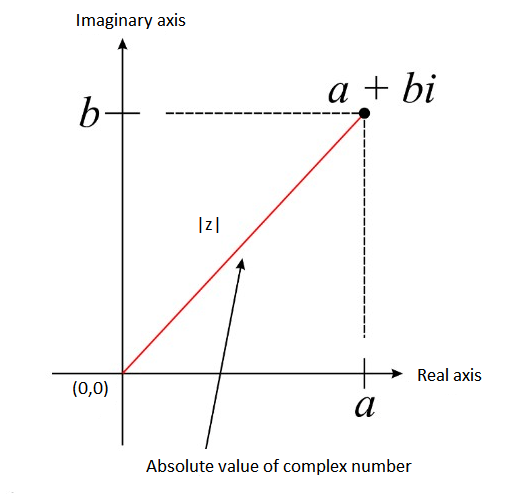

Absolute Value (modulus ) of a Complex Number

\(|5|=5\)

\(|-5|=5\)

\(|z|=|a+b i|=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}\)

This is also called the modulus of a complex number.

Solution: \(|3+2 i|=\sqrt{3^2+2^2}\)

\(=\sqrt{9+4}\)

\(=\sqrt{13}\)

The absolute value of \(3+2 i=\sqrt{13}\).

Example 2: Find \(|1-3 i|\).

Solution: \(|1-3 i|=\sqrt{1^2+3^2}\)

\(=\sqrt{1+9}\)

\(=\sqrt{10}\)

Therefore, \(|1-3 i|=\sqrt{10}\).

Example 3: If \(z\) is a complex number of magnitude \(\sqrt{45}\) and its real part is 3 . Find the imaginary part and \(z\).

Solution: Let \(z=a+ib\), \(\sqrt{a^2+b^2}=\sqrt{45}\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\sqrt{3^2+b^2}=\sqrt{45} \\

&\sqrt{9+b^2}=\sqrt{45} \\

&9+b^2=45 \\

&b^2=45-9 \\

&b^2=36 \\

&b=\sqrt{36} \\

&b=\pm 6

\end{aligned}

\)

The complex number \(z=3\pm 6 i\)

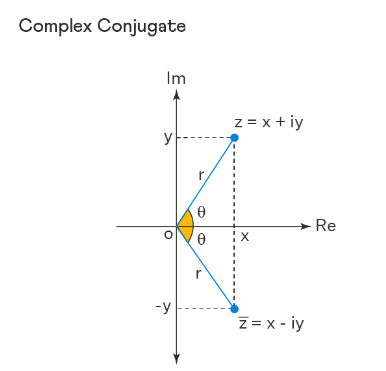

Complex Conjugate Number

The complex conjugate of a complex number, z, is its mirror image with respect to the horizontal axis (or \(x\)-axis). The complex conjugate of complex number \(z\) is denoted by \(\bar{z}\). An easy way to determine the conjugate of a complex number is to replace ‘ \(i\) ‘ with ‘- \(i\) ‘ in the original complex number. The complex conjugate of \(x+iy\) is \(x- iy\) and the complex conjugate of \(x- iy\) is \(x+iy\). As in the image given below, if the complex number z lies in the first quadrant, its image about the horizontal axis, that is, the complex conjugate \(\bar{z}\) lies in the fourth quadrant.

Properties of conjugate: If \(\mathrm{z}, \mathrm{z}_1, \mathrm{z}_2\) are complex numbers, then

(i) \(\overline{\overline{(z)}}=z\)

(ii) \(z+\bar{z}=2 \operatorname{Re}(z)\)

(iii) \(z-\bar{z}=2 i \operatorname{Im}(z)\)

(iv) \(z=\bar{z} \Leftrightarrow z\) is purely real

(v) \(z+\bar{z}=0 \Rightarrow z\) is purely imaginary

(vi) \(z \bar{z}=\{\operatorname{Re}(z)\}^2+\{\operatorname{Im}(z)\}^2\)

(vii) \(\overline{z_1+z_2}=\overline{z_1}+\overline{z_2}\)

(viii) \(\overline{z_1-z_2}=\overline{z_1}-\overline{z_2}\)

(ix) \(\overline{z_1 z_2}=\overline{z_1}\) \(\overline{z_2}\)

(x) \(\frac{z_1}{z_2}=\frac{\overline{z_1}}{\overline{z_2}}, z_2 \neq 0\).

Example 4: Find the complex conjugate of \(5-3 \mathbf{i}\)

Solution: \(5+3 \mathbf{i}\) (Replace \(\mathbf{i}\) with \(\mathbf{-i}\))

Example 5: Prove that \(z \bar{z}=|z|^2\), where \(z=a+i b\) is a complex number and \(\bar{z}\) its conjugate.

Proof: Let \(z=a+i b\) be a complex number. Then, the modulus of \(z\), denoted by \(|z|\), is defined to be the non-negative real number \(\sqrt{a^2+b^2}\), i.e., \(|z|=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}\) and the conjugate of \(z\), denoted as \(\bar{z}\), is the complex number \(a-i b\), i.e., \(\bar{z}=a-i b\).

Observe that the multiplicative inverse of the non-zero complex number \(z\) is given by

\(

z^{-1}=\frac{1}{a+i b}=\frac{a}{a^2+b^2}+i \frac{-b}{a^2+b^2}=\frac{a-i b}{a^2+b^2}=\frac{\bar{z}}{|z|^2}

\)

or \(\quad z \bar{z}=|z|^2\)

Important Note:

For any two complex numbers \(z_1\) and \(z_2\), we have

(i) \(\left|z_1 z_2\right|=\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right|\)

(ii) \(\left|\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right|=\frac{\left|z_1\right|}{\left|z_2\right|}\) provided \(\left|z_2\right| \neq 0\)

Example 6: Find the multiplicative inverse of \(2-3 i\).

Solution: Let \(z=2-3 i\)

Then \(\quad \bar{z}=2+3 i\) and \(\quad|z|^2=2^2+(-3)^2=13\)

Therefore, the multiplicative inverse of \(2-3 i\) is given by

\(z^{-1}=\frac{\bar{z}}{|z|^2}=\frac{2+3 i}{13}=\frac{2}{13}+\frac{3}{13} i\)

The above working can be reproduced in the following manner also,

\(

\begin{aligned}

z^{-1} &=\frac{1}{2-3 i}=\frac{2+3 i}{(2-3 i)(2+3 i)} \\

&=\frac{2+3 i}{2^2-(3 i)^2}=\frac{2+3 i}{13}=\frac{2}{13}+\frac{3}{13} i

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 7: Express the following in the form \(a+i b\)

(i) \(\frac{5+\sqrt{2} i}{1-\sqrt{2} i}\)

(ii) \(i^{-35}\)

Solution: (i) We have, \(\frac{5+\sqrt{2} i}{1-\sqrt{2} i}=\frac{5+\sqrt{2} i}{1-\sqrt{2} i} \times \frac{1+\sqrt{2} i}{1+\sqrt{2} i}=\frac{5+5 \sqrt{2} i+\sqrt{2} i-2}{1-(\sqrt{2} i)^2}\)

\(=\frac{3+6 \sqrt{2} i}{1+2}=\frac{3(1+2 \sqrt{2} i)}{3}=1+2 \sqrt{2} i .

\)

(ii) \(i^{-35}=\frac{1}{i^{35}}=\frac{1}{\left(i^2\right)^{17} i}=\frac{1}{-i} \times \frac{i}{i}=\frac{i}{-i^2}=i\)

Example 8: The conjugate of a complex number is \(\frac{1}{i-1}\). Then, that complex number is [AIEEE 2008]

(a) \(\frac{-1}{i+1}\)

(b) \(\frac{1}{i-1}\)

(c) \(\frac{-1}{i-1}\)

(d) \(\frac{1}{i+1}\)

Solution: (a) Let the required complex number be \(z\). Then,

\(

\bar{z}=\frac{1}{i-1} \Rightarrow z=\left(\overline{\frac{1}{i-1}}\right)=\frac{1}{-i-1}=-\frac{1}{i+1}

\)

Example 9: If \(\operatorname{Im}\left(\frac{z-1}{2 z+1}\right)=-4\), then the locus of \(z\) is [CEE (Delhi) 2006]

(a) an ellipse

(b) a parabola

(c) a straight line

(d) a circle

Solution: (d) Let \(z=x+i y\). Then,

\(

\frac{z-1}{2 z+1}=\frac{(x-1)+i y}{(2 x+1)+2 i y}=\frac{\mid(x-1)+i y)|(2 x+1)-2 i y|}{|(2 x+1)+2 i y||(2 x+1)-2 i y|}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad \frac{z-1}{2 z+1}=\frac{\left|(x-1)(2 x+1)+2 y^2\right|+i|y(2 x+1)-2 y(x-1)|}{(2 x+1)^2+4 y^2} \\

& \therefore \quad \operatorname{Im}\left(\frac{z-1}{2 z+1}\right)=\frac{3 y}{(2 x+1)^2+4 y^2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Now, \(\operatorname{Im}\left(\frac{z-1}{2 z+1}\right)=-4\)

\(

\Rightarrow \quad \frac{3 y}{(2 x+1)^2+4 y^2}=-4 \Rightarrow x^2+y^2+x+\frac{3}{16} y+\frac{1}{4}=0

\)

Clearly, it represents a circle.

\(

x^2+x+y^2+\frac{3}{16} y=-\frac{1}{4}

\)

Add the square of half the coefficient of \(x\) (which is \(\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^2=\frac{1}{4}\) ) to both sides:

\(

\begin{gathered}

x^2+x+\frac{1}{4}+y^2+\frac{3}{16} y=-\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{4} \\

\left(x+\frac{1}{2}\right)^2+y^2+\frac{3}{16} y=0

\end{gathered}

\)

Add the square of half the coefficient of \(y\) (which is \(\left(\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{16}\right)^2=\left(\frac{3}{32}\right)^2=\frac{9}{1024}\) ) to both sides:

\(

\begin{gathered}

\left(x+\frac{1}{2}\right)^2+y^2+\frac{3}{16} y+\frac{9}{1024}=0+\frac{9}{1024} \\

\left(x+\frac{1}{2}\right)^2+\left(y+\frac{3}{32}\right)^2=\frac{9}{1024}

\end{gathered}

\)

The equation is now in the standard form \((x-h)^2+(y-k)^2=r^2\).

The center of the circle \((h, k)\) is \(\left(-\frac{1}{2},-\frac{3}{32}\right)\), and the radius \(r\) is \(\sqrt{\frac{9}{1024}}=\frac{3}{32}\).

Since the radius squared \(\left(r^2=\frac{9}{1024}\right)\) is positive, the equation describes a real circle.

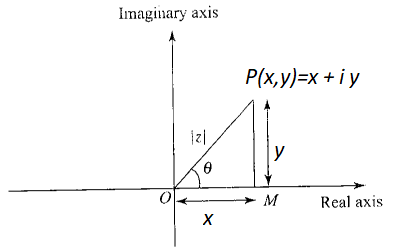

Modulus of a Complex Number

The length of the line segment \(O P\) is called the modulus of \(z\) and is denoted by \(|z|\). From Figure above, we have

\(

\begin{aligned}

O P^2 & =O M^2+M P^2 \\

\Rightarrow \quad O P^2 & =x^2+y^2 \Rightarrow O P=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}

\end{aligned}

\)

Thus,

\(

|z|=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}=\sqrt{\{\operatorname{Re}(z)\}^2+\{\operatorname{Im}(z)\}^2}

\)

Clearly, \(|z| \geq 0\) for all \(z \in C\).

If \(z_1=3-4 i, z_2=-5+2 i\) and \(z_3 =1+\sqrt{-3}\), then \(\left|z_1\right|=\sqrt{3^2+(-4)^2}=5,\left|z_2\right|=\sqrt{(-5)^2+2^2}=\sqrt{29}\) and \(\left|z_3\right|=|1+i \sqrt{3}|=\sqrt{1^2+(\sqrt{3})^2}=2\).

Remark: In the set \(C\) of all complex numbers, the order relation is not defined. As such \(z_1>z_2\) or \(z_1<z_2\) has no meaning but \(\left|z_1\right|>\left|z_2\right|\) or \(\left|z_1\right|<\left|z_2\right|\) has got its meaning since \(\left|z_1\right|\) and \(\left|z_1\right|\) are real numbers.

Argument of Complex Number

The angle \(\theta\) which \(O P\) makes with \(x\)-axis is called the argument or amplitude of \(z\) and is denoted by \(\arg (z)\) or \(\operatorname{amp}(z)\). From Figure above, we have

\(

\tan \theta=\frac{P M}{O M}=\frac{y}{x}=\frac{\operatorname{Im}(z)}{\operatorname{Re}(z)} \Rightarrow \theta=\tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{\operatorname{Im}(z)}{\operatorname{Re}(z)}\right)

\)

This angle \(\theta\) has infinitely many values differing by multiples of \(2 \pi\).

Example 10: If \(z=1+i \tan \alpha\), where \(\pi<\alpha<3 \pi / 2\), then \(|z|\) is equal to

(a) \(\sec \alpha\)

(b) \(-\sec \alpha\)

(c) \(\operatorname{cosec} \alpha\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& z=1+i \tan \alpha \\

\Rightarrow \quad & |z|=\sqrt{1+\tan ^2 \alpha}=|\sec \alpha|=-\sec \alpha

\end{aligned}

\)

Properties of Modulus:

Theorem: If \(z, z_1, z_2 \in C\), then

(i) \(|z|=0 \Leftrightarrow z=0\) i.e. \(\operatorname{Re}(z)=\operatorname{Im}(z)=0\)

(ii) \(|z|=|\bar{z}|=|-z|\)

(iii) \(-|z| \leq \operatorname{Re}(z) \leq|z| ;-|z| \leq \operatorname{Im}(z) \leq|z|\)

(iv) \(z \bar{z}=|z|^2\)

(v) \(\left|z_1 z_2\right|=\left|z_1\right|\left|z_2\right|\)

(vi) \(\left|\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right|=\frac{\left|z_1\right|}{\left|z_2\right|}, z_2 \neq 0\)

(vii) \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|^2=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2+2 \operatorname{Re}\left(z_1 \overline{z_2}\right)\)

(viii) \(\left|z_1-z_2\right|^2=\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2-2 \operatorname{Re}\left(z_1 \overline{z_2}\right)\)

(ix) \(\left|z_1+z_2\right|^2+\left|z_1-z_2\right|^2=2\left(\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2\right)\)

(x) \(\left|a z_1-b z_2\right|^2+\left|b z_1+a z_2\right|^2=\left(a^2+b^2\right)\left(\left|z_1\right|^2+\left|z_2\right|^2\right)\), where \(a, b \in R\).

Reciprocal of a Complex Number

Let \(z\) be a complex number. Then,

\(

\frac{1}{z}=\frac{\bar{z}}{z \bar{z}}=\frac{\bar{z}}{|z|^2}

\)

Example 11: If \(\left|\frac{z+i}{z-i}\right|=\sqrt{3}\), then the radius of the circle is [CEE (Delhi) 2007]

(a) \(\frac{2}{\sqrt{21}}\)

(b) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{21}}\)

(c) \(\sqrt{3}\)

(d) \(\sqrt{21}\)

Solution: (c) We have,

\(

\left|\frac{z+i}{z-i}\right|=\sqrt{3}

\)

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \Rightarrow \quad|z+i|=\sqrt{3}|z-i| \\

& \Rightarrow \quad|x+i(y+1)|=\sqrt{3}|x+i(y-1)| \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x^2+(y+1)^2=3\left\{x^2+(y-1)^2\right\} \\

& \Rightarrow \quad x^2+y^2-4 y+1=0 \\

& \Rightarrow \quad(x-0)^2+(y-2)^2=(\sqrt{3})^2

\end{aligned}

\)

Clearly, it represents a circle of radius \(\sqrt{3}\).

Example 12: The smallest positive integral value of \(n\) for which \(\left(\frac{1-i}{1+i}\right)^n\) is purely imaginary with positive imaginary part, is

(a) 1

(b) 3

(c) 5

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\left(\frac{1-i}{1+i}\right)^n=\left(\frac{1-i}{1+i} \times \frac{1-i}{1-i}\right)^n=\left(\frac{1-2 i+i^2}{1-i^2}\right)^n=(-i)^n

\)

\(\therefore \quad\left(\frac{1-i}{1+i}\right)^n\) will be purely imaginary if \(n\) is an odd integer.

For \(n=1\), we have \(\left(\frac{1+i}{1-i}\right)^1=(-i)^1=-i\), which has negative imaginary part.

For \(n=3\), we have

\(\left(\frac{1+i}{1-i}\right)^3=(-i)^3=i\), which has positive imaginary part.

Hence, \(n=3\).

Example 13: The least positive integer \(n\) for which \(\left(\frac{1+i}{1-i}\right)^n\) is real, is

(a) 2

(b) 4

(c) 8

(d) none of these

Solution: (a) We have,

\(

\left(\frac{1+i}{1-i}\right)^n=\left(\frac{(1+i)^2}{1-i^2}\right)^n=(i)^n

\)

Clearly, it is real for \(n=2\).

Example 14: The smallest positive integer \(n\) for which \(\frac{(1+i)^n}{(1-i)^{n-2}}\) is a real number, is [CEE (Delhi) 2001]

(a) 2

(b) 1

(c) 3

(d) 4

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{(1+i)^n}{(1-i)^{n-2}}=\left(\frac{1+i}{1-i}\right)^n(1-i)^2 \\

\Rightarrow \quad & \frac{(1+i)^n}{(1-i)^{n-2}}=\left\{\frac{(1+i)^2}{1-i^2}\right\}\left(1-2 i+i^2\right)=(i)^n(-2 i)=-2 i^{n+1}

\end{aligned}

\)

This will be a real number if \(n+1\) is an even integer i.e. \(n\) is an odd integer.

Since the smallest odd positive integer is 1. Therefore, \(n=1\).

Example 15: If \(z=x-iy\) and \(z^{1 / 3}=p+i q\), then \(\left(\frac{x}{p}+\frac{y}{q}\right) / p^2+q^2\) is equal to [AIEEE 2004]

(a) -2

(b) -1

(c) 2

(d) 1

Solution: (a) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& z=x-i y \text { and } z^{1 / 3}=p+i q \\

\Rightarrow & z=x-i y \text { and } z=(p+i q)^3 \\

\Rightarrow & x-i y=(p+i q)^3 \\

\Rightarrow & x-i y=\left(p^3-3 p q^2\right)+i\left(-3 p^2 q+q^3\right) \\

\Rightarrow & x=p^3-3 p q^2 \text { and } y=q^3-3 p^2 q \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{x}{p}+\frac{y}{q}=\left(p^2+q^2\right)-3\left(p^2+q^2\right) \Rightarrow \frac{\frac{x}{p}+\frac{y}{q}}{p^2+q^2}=-2 .

\end{aligned}

\)

Example 16: If \(z=x+i y, z^{1 / 3}=a-i b\) and \(\frac{x}{a}-\frac{y}{b}=k\left(a^2-b^2\right)\), then the value of \(k\) equals [CEE (Delhi) 2005)]

(a) 2

(b) 4

(c) 6

(d) 1

Solution: (b) We have,

\(

\begin{aligned}

& z=x+i y \text { and } z^{1 / 3}=a-i b \\

\Rightarrow & x+i y=(a-i b)^3 \\

\Rightarrow & x+i y=\left(a^3-3 a b^2\right)+i\left(-3 a^2 b+b^3\right) \\

\Rightarrow & x=a^3-3 a b^2 \text { and } y=-3 a^2 b+b^3 \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{x}{a}-\frac{y}{b}=a^2-3 b^2+3 a^2-b^2 \\

\Rightarrow & \frac{x}{a}-\frac{y}{b}=4\left(a^2-b^2\right) \\

\Rightarrow & k\left(a^2-b^2\right)=4\left(a^2-b^2\right) \quad \quad\left[\because \frac{x}{a}-\frac{y}{b}=k\left(a^2-b^2\right)\right] \\

\Rightarrow & k=4

\end{aligned}

\)

Square Root of a Complex Number

Let \(a+i b\) be a complex number such that \(\sqrt{a+i b}=x+i y\), where \(x\) and \(y\) are real numbers. Then,

\(

\begin{array}{ll}

\sqrt{a+i b} & =x+i y \\

\Rightarrow \quad(a+i b) & =(x+i y)^2 \\

\Rightarrow \quad a+i b & =\left(x^2-y^2\right)+2 i x y

\end{array}

\)

On equating real and imaginary parts, we get

\(

\begin{aligned}

&\begin{aligned}

& x^2-y^2=a \dots(i)\\

& 2 x y=b

\end{aligned}\\

&\text { Now, }\\

&\begin{aligned}

& \left(x^2+y^2\right)^2=\left(x^2-y^2\right)^2+4 x^2 y^2 \\

\Rightarrow & \left(x^2+y^2\right)^2=a^2+b^2 \\

\Rightarrow & \left(x^2+y^2\right)=\sqrt{a^2+b^2} \quad\left[\because x^2+y^2 \geq 0\right] \dots(ii)

\end{aligned}

\end{aligned}

\)

Solving equations (i) and (ii), we get

\(

\begin{aligned}

x^2 & =\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\left[\sqrt{a^2+b^2}+a\right] \text { and } y^2=\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\left[\sqrt{a^2+b^2}-a\right] \\

\Rightarrow x & = \pm \sqrt{\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\left[\sqrt{a^2+b^2}+a\right]} \text { and } y= \pm \sqrt{\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\left[\sqrt{a^2+b^2}-a\right]}

\end{aligned}

\)

If \(b\) is positive, then by the relation \(2 x y=b, x\) and \(y\) are of the same sign. Hence,

\(

\sqrt{a+i b}= \pm\left\{\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left[\sqrt{a^2+b^2}+a\right]}+i \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left[\sqrt{a^2+b^2}-a\right]}\right\}

\)

If \(b\) is negative, then by the relation \(2 x y=b, x\) and \(y\) are of different signs. Hence,

\(

\sqrt{a+i b}= \pm\left\{\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left[\sqrt{a^2+b^2}+a\right]}-i \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left[\sqrt{a^2+b^2}-a\right]}\right\}

\)

Remark: The square root of a complex number \(z\) is given by

\(\sqrt{z}= \pm\left[\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\{|z|+\operatorname{Re}(z)\}}+i \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\{|z|-\operatorname{Re}(z)\}}\right], \text { if } \operatorname{Im}|z|>0\)

and, \(\sqrt{z}= \pm\left[\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\{|z|+\operatorname{Re}(z)\}}-i \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\{|z|-\operatorname{Re}(z)\}}\right]\), if \(\operatorname{Im}|z|<0\)

Example 17: Taking the value of the square root with positive real part only, the value of \(\sqrt{7+24 i}+\sqrt{-7-24 i}\) is

(a) \(1+7 i\)

(b) \(-1-7 i\)

(c) \(7-i\)

(d) \(-7+i\)

Solution: (c) If \(z=a+i b\), then

\(

\begin{array}{rlrl}

& \sqrt{a \pm i b} = \pm\left\{\sqrt{\frac{|z|+\operatorname{Re}(z)}{2}} \pm i \sqrt{\frac{|z|-\operatorname{Re}(z)}{2}}\right\} \\

& \therefore \sqrt{7+24 i} = \pm(4+3 i) \text { and, } \sqrt{-7-24 i}= \pm(3-4 i) \\

\therefore \sqrt{7+24 i} & \pm \sqrt{-7-24 i} \\

& =4+3 i +3-4 i=7-i \quad \text { [Taking +ive real part only]] }

\end{array}

\)

Example 18: Given that the real parts of \(\sqrt{5+12 i}\) and \(\sqrt{5-12 i}\) are positive. The value of \(z=\frac{\sqrt{5+12 i}+\sqrt{5-12 i}}{\sqrt{5+12 i}-\sqrt{5-12 i}}\), is

(a) \(\frac{3}{2} i\)

(b) \(\frac{-3}{2} i\)

(c) \(-3+\frac{2}{5} i\)

(d) none of these

Solution: (b) Taking positive real parts, we have

\(

\sqrt{5+12 i}=\sqrt{\frac{13+5}{2}}+i \sqrt{\frac{13-5}{2}}=3+2 i

\)

and, \(\sqrt{5-12 i}=\sqrt{\frac{13+5}{2}}-i \sqrt{\frac{13-5}{2}}=3-2 i\)

\(

\therefore \quad z=\frac{(3+2 i)+(3-2 i)}{(3+2 i)-(3-2 i)}=\frac{6}{4 i}=\frac{-3}{2} i

\)

Example 19: Find the value of \(\frac{i^{592}+i^{590}+i^{588}+i^{586}+i^{584}}{i^{582}+i^{580}+i^{578}+i^{576}+i^{574}}-1\)

Solution: The given expression is \(\frac{i^{592}+i^{590}+i^{588}+i^{586}+i^{584}}{i^{582}+i^{580}+i^{578}+i^{576}+i^{574}}-1\). We observe a common factor in the numerator related to the denominator. The difference in powers is \(592-582=10\).

We can factor out \(i^{10}\) from the numerator terms:

\(

i^{592}+i^{590}+i^{588}+i^{586}+i^{584}=i^{10}\left(i^{582}+i^{580}+i^{578}+i^{576}+i^{574}\right)

\)

The fraction simplifies to:

\(

\frac{i^{10}\left(i^{582}+i^{580}+i^{578}+i^{576}+i^{574}\right)}{i^{582}+i^{580}+i^{578}+i^{576}+i^{574}}=i^{10}

\)

The expression becomes \(i^{10}-1\).

Evaluate the power of the imaginary unit

The imaginary unit \(i\) has the property that its powers cycle every four integers: \(i^1=i\), \(i^2=-1, i^3=-i, i^4=1\). We can determine \(i^{10}\) by finding the remainder when 10 is divided by 4 , which is 2.

\(

i^{10}=i^{4 \cdot 2+2}=\left(i^4\right)^2 \cdot i^2=1^2 \cdot(-1)=-1

\)

Substituting this value back into the simplified expression \(i^{10}-1\) :

\(

-1-1=-2

\)

Example 20: The value of \(i^{1+3+5+\cdots+(2 n+1)}\) is ____.

Solution: Step 1: Sum the exponent series

The exponent is an arithmetic series of odd numbers: \(S=1+3+5+\ldots+(2 n+1)\). There are \(n+1\) terms in this series. The sum of the first \(k\) odd integers is \(k^2\).

Therefore, the sum \(S\) is given by:

\(

S=(n+1)^2

\)

Step 2: Evaluate the power of \(i\)

The expression becomes \(i^S=i^{(n+1)^2}\). The value of \(i^m\) cycles every four powers depending on \(m(\bmod 4)\). We analyze \((n+1)^2(\bmod 4)\) (Modulo 4 means finding the remainder after dividing by 4):

\(

(n+1)^2=n^2+2 n+1

\)

If \(n\) is even, \(n=2 k\), then \(S=(2 k+1)^2=4 k^2+4 k+1 \equiv 1(\bmod 4)\).

If \(n\) is odd, \(n=2 k+1\), then \(S=(2 k+2)^2=4(k+1)^2 \equiv 0(\bmod 4)\).

Step 3: Determine the final value

The value of the expression is \(i^S\).

If \(n\) is even, \(i^S=i^1=i\).

If \(n\) is odd, \(i^S=i^0=1\).

The value of the expression is \(\boldsymbol{i}\) for even \(\boldsymbol{n}\) and \(\mathbf{1}\) for odd \(\boldsymbol{n}\).