5.6 Genetic Code

During replication and transcription a nucleic acid was copied to form another nucleic acid. Hence, these processes are easy to conceptualise on the basis of complementarity. The process of translation requires transfer of genetic information from a polymer of nucleotides to synthesise a polymer of amino acids. Neither does any complementarity exist between nucleotides and amino acids, nor could any be drawn theoretically. There existed ample evidences, though, to support the notion that change in nucleic acids (genetic material) were responsible for change in amino acids in proteins. This led to the proposition of a genetic code that could direct the sequence of amino acids during synthesis of proteins.

If determining the biochemical nature of genetic material and the structure of DNA was very exciting, the proposition and deciphering of genetic code were most challenging. In a very true sense, it required involvement of scientists from several disciplines – physicists, organic chemists, biochemists and geneticists. It was George Gamow, a physicist, who argued that since there are only 4 bases and if they have to code for 20 amino acids, the code should constitute a combination of bases. He suggested that in order to code for all the 20 amino acids, the code should be made up of three nucleotides. This was a very bold proposition, because a permutation combination of \(4^3(4 \times 4 \times 4)\) would generate 64 codons; generating many more codons than required.

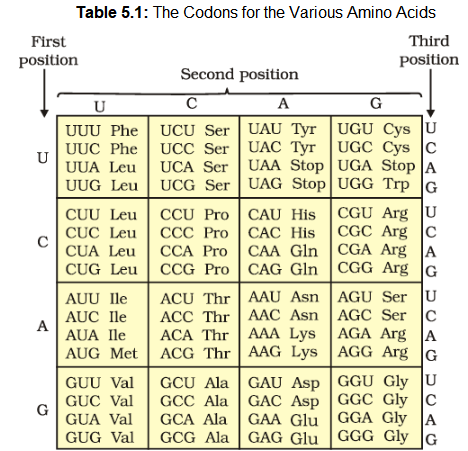

Providing proof that the codon was a triplet, was a more daunting task. The chemical method developed by Har Gobind Khorana was instrumental in synthesising RNA molecules with defined combinations of bases (homopolymers and copolymers). Marshall Nirenberg’s cell-free system for protein synthesis finally helped the code to be deciphered. Severo Ochoa enzyme (polynucleotide phosphorylase) was also helpful in polymerising RNA with defined sequences in a template independent manner (enzymatic synthesis of RNA). Finally a checker-board for genetic code was prepared which is given in Table 5.1.

The salient features of genetic code are as follows:

- (i) The codon is triplet. 61 codons code for amino acids and 3 codons do not code for any amino acids, hence they function as stop codons.

- (ii) Some amino acids are coded by more than one codon, hence the code is degenerate.

- (iii) The codon is read in mRNA in a contiguous fashion. There are no punctuations.

- (iv) The code is nearly universal: for example, from bacteria to human UUU would code for Phenylalanine (phe). Some exceptions to this rule have been found in mitochondrial codons, and in some protozoans.

- (v) AUG has dual functions. It codes for Methionine (met), and it also act as initiator codon.

- (vi) UAA, UAG, UGA are stop terminator codons.

If following is the sequence of nucleotides in mRNA, predict the sequence of amino acid coded by it (take help of the checkerboard):

-AUG UUU UUC UUC UUU UUU UUC-

Now try the opposite. Following is the sequence of amino acids coded by an mRNA. Predict the nucleotide sequence in the RNA:

Met-Phe-Phe-Phe-Phe-Phe-Phe

Do you face any difficulty in predicting the opposite?

Can you now correlate which two properties of genetic code you have learnt?

Mutations and Genetic Code

The relationships between genes and DNA are best understood by mutation studies. You have studied about mutation and its effect in Chapter 4. Effects of large deletions and rearrangements in a segment of DNA are easy to comprehend. It may result in loss or gain of a gene and so a function. The effect of point mutations will be explained here. A classical example of point mutation is a change of single base pair in the gene for beta globin chain that results in the change of amino acid residue glutamate to valine. It results into a diseased condition called as sickle cell anemia. Effect of point mutations that inserts or deletes a base in structural gene can be better understood by following simple example.

Consider a statement that is made up of the following words each having three letters like genetic code.

RAM HAS RED CAP

If we insert a letter B in between HAS and RED and rearrange the statement, it would read as follows:

RAM HAS BRE DCA P

Similarly, if we now insert two letters at the same place, say BI’. Now it would read,

RAM HAS BIR EDC AP

Now we insert three letters together, say BIG, the statement would read

RAM HAS BIG RED CAP

The same exercise can be repeated, by deleting the letters R, E and D, one by one and rearranging the statement to make a triplet word.

RAM HAS EDC AP

RAM HAS DCA P

RAM HAS CAP

The conclusion from the above exercise is very obvious. Insertion or deletion of one or two bases changes the reading frame from the point of insertion or deletion. However, such mutations are referred to as frameshift insertion or deletion mutations. Insertion or deletion of three or its multiple bases insert or delete in one or multiple codon hence one or multiple amino acids, and reading frame remains unaltered from that point onwards.

tRNA– the Adapter Molecule

From the very beginning of the proposition of code, it was clear to Francis Crick that there has to be a mechanism to read the code and also to link it to the amino acids, because amino acids have no structural specialities to read the code uniquely. He postulated the presence of an adapter molecule that would on one hand read the code and on other hand would bind to specific amino acids. The tRNA, then called sRNA (soluble RNA), was known before the genetic code was postulated. However, its role as an adapter molecule was assigned much later.

tRNA has an anticodon loop that has bases complementary to the code, and it also has an amino acid acceptor end to which it binds to amino acids. tRNAs are specific for each amino acid (Figure 5.12). For initiation, there is another specific tRNA that is referred to as initiator tRNA. There are no tRNAs for stop codons. In figure 5.12, the secondary structure of tRNA has been depicted that looks like a clover-leaf. In actual structure, the tRNA is a compact molecule which looks like inverted L.